Judge Judy’s Law

Julia Longoria: A quick note: There will be some swearing in this one.

(An old TV switches on. Through the electric hum and static, a piano solemnly plays the melody of Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 5.” As the main line of the melody ends, the TV switches off to silence. Then a phone rings.)

Victoria Bresnan: Hello, Petey!

Peter Bresnan: Hey, Mama.

Longoria: We’re kicking things off this week with producer Peter Bresnan and his mom, Victoria.

Victoria: How are you, bubby?

Peter: I’m doing good. How are you?

Victoria: I’m good. [A gentle, familiar laugh rings in her voice.] I’m good.

Peter Bresnan: When I was growing up, my mom and I used to spend hours and hours sitting in our living room, watching this one particular TV show—[Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 5” reemerges suddenly.]—one of the most famous and influential court shows ever made.

(This version of Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 5” is a high-intensity remix, updated with a drum line and punchier, staccato notes.)

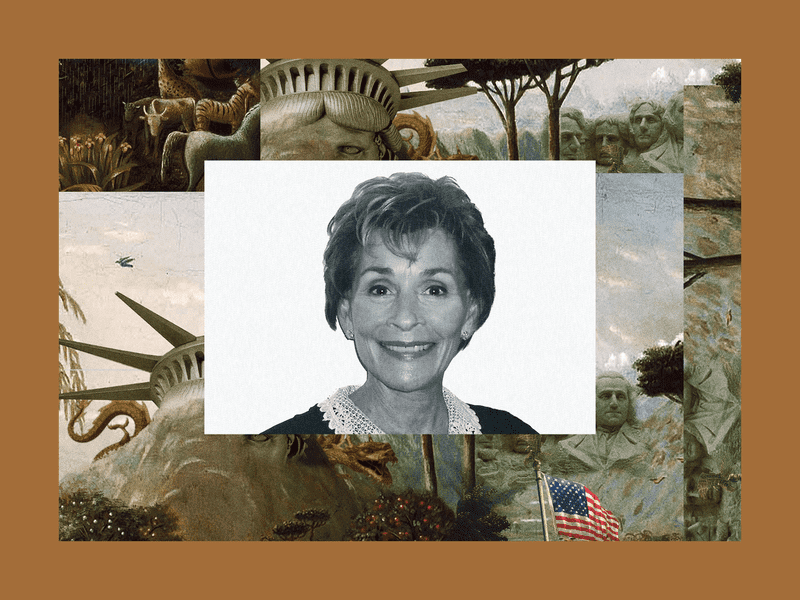

Voice-over: (In a high-drama voice, low and serious and emphatic.) You are about to enter the courtroom of Judge Judith Sheindlin. The people are real. The cases are real. The rulings are final. This is Judge Judy.

(The show’s intro music cuts out.)

Peter: How long have you been watching Judge Judy for?

Victoria: Probably about 30 years.

Peter: My mom started letting me watch Judge Judy when I was, like, 12 or 13. And it’s gotten to the point now where if I [A beat.] am in a hotel room and I turn on the TV and Judge Judy is on, it’s like I—it’s like I can smell the leather of my parents’ sofa. And I just picture my mom and I sitting on the couch and watching the show together.

Victoria: I think that I could never watch it again without thinking of you.

Peter: And—yeah. And I can’t watch it without thinking about you.

Victoria: (A light chuckle.) We laugh over them. You know, we joke about them. We have conversations about it. I almost used it as a learning tool. It gave me opportunities to share the message that I had as a mother through Judge Judy.

(A curious melody plinks out through a tinny synthesizer, undergirded by a plunky, bouncy bass line. It feels almost mysterious, a little serious.)

Judge Judy: I want to tell you both that I’ve read your sworn depositions. And I don’t believe either one of you. [The crowd laughs.] Let’s start out with that.

Peter: The premise of the show is that people who have filed lawsuits in small-claims court—they come on the show, and they have their disputes adjudicated by this former New York City family-court judge named Judy Sheindlin.

Judge Judy: (In a strained voice, as she slams the gavel down three times.) I’m speaking.

Peter: She, uh, takes no prisoners. She says exactly what she thinks.

Judge Judy: Listen to me; you say no, I say yes. I’m the law.

Defendant: I’m sorry, Your Honor.

Judge Judy: I’m the law.

Peter: And she runs her courtroom with this speed and energy and, like, a no-bullshit attitude that is just incredibly compelling to watch.

Judge Judy: I don’t care what you believe. Maybe your mother cares how you feel. Maybe your sister cares how you feel. [Reemphasizing the word as if spitting out food that didn’t sit well.] “Feel”! The law doesn’t give a rat’s ass how you feel.

(A flourish in the music—synthesized horns, perhaps?—signals the end of the music.)

Victoria: I liked her honesty. I just thought she would just say things that maybe a lot of judges or attorneys or whatever would not say.

Peter: My mom has never really spent that much time in court. And I haven’t spent much time in court either. Like, aside from jury duty. And I think, for us, Judge Judy really felt like a window into how the American court system works.

Victoria: I—I have to believe that it’s very, very representative of how the justice system is.

Peter: And, you know, there’s, like, a bailiff and this big judge’s bench where Judy sits at, and there’s all these legal books everywhere. And also Judy is just saying constantly in the show …

(A droning hum plays like an organ.)

(A montage of clips from the show begins.)

Judge Judy: This is a court.

Judge Judy: This is a court.

Judge Judy: This is a court.

Judge Judy: You’re here.

Defendant: Yes.

Judge Judy: This is a court.

Judge Judy: Didn’t you know you were coming to court today?

Judge Judy: This is not the beach. This is the court. Today you were coming to court.

(The montage ends.)

Peter: And I think that feeling of authenticity is really the core of Judge Judy’s appeal.

By the time the show finished its run in 2021, it had around 10 million viewers, five days a week. Again and again, it beat out Oprah and became the most-watched daytime-TV show in America.

So, for decades, large swaths of Americans, including myself, have tuned into Judge Judy looking for some kind of guidance about how the justice system works. And it really wasn’t until recently that I started to wonder about the impact of that. I imagined the millions of families like mine sitting on millions of couches in front of millions of TVs, formulating their ideas about crime and justice from this TV show that purports to be really real.

(The drone ends.)

Voice-over: (With Beethoven’s music as part of the show intro.) The people are real. The cases are real.

Peter: And it made me want to know: How real is Judge Judy, actually?

(A soft, scratchy record plays like a lullaby, like dust motes floating lazily through an afternoon sunbeam.)

Peter: And I learned that, despite what Judy says on the show over and over and over again, what you see on Judge Judy is not actually a court.

It’s like this bizarro mirror version of the American courtroom that really seems like the real thing but operates by a totally different set of rules.

(A beat.)

Longoria: This week, producer Peter Bresnan tells a story of American justice, as seen on TV. The unreal show that, for some millions of Americans, has served as a real intro to our court system.

So when we hold up Judge Judy as a mirror, what can “Judy’s law” tell us about us—and the speed and cost of the way we do justice?

I’m Julia Longoria. This is The Experiment, a show about our unfinished country.

(A few beeps and the lullaby dissolves.)

Peter: So Judge Judy emerged from this very specific moment in the history of television. It was the early 1990s, and court TV was dead.

Larry Lyttle: There was zero appetite for one. Zero. Nobody said, “Get me a courtroom show.”

Peter: This is Larry Lyttle. He was a television executive at the time, and the president of a production company called Big Ticket Television.

Peter Bresnan: Why had the public lost interest in that kind of court show?

Lyttle: After a certain point in time, they became mundane, Peter. They became the same type of narratives. “Okay, so it wasn’t my cousin who stole my toaster oven. It was my wife.”

Voice-over: (Over rapid bongos—the intro to the 1980s version of The People’s Court.) What you are witnessing is real. The participants are not actors. They are actual … (Fades under.)

Peter: In the 1980s, one of the most popular of these court shows was called The People’s Court. And The People’s Court tried real cases from real small-claims court in front of this retired California judge named Joseph Wapner.

Judge Joseph Wapner: (Very dryly.) After you bought the car, you found some problems with it …

Peter: But Wapner was not exactly the most electric TV personality.

Judge Wapner: Did she lend you a mobile credit card?

Litigant: Yes, she did.

Peter: He didn’t really jump in and interrupt people or do any name-calling.

Judge Wapner: Did you run up these two bills of $18.58 and $344.73?

Litigant: Yes.

Judge Wapner: Did you pay them?

Litigant: (In a voice that could almost be construed as mocking.) No.

Peter: It really seems like he thought his job as a judge was just to listen and hear both sides and render an impartial verdict.

Judge Wapner: (Fades up.) Let me give it some thought. Let me give it some thought, uh, and take a short recess and, uh, see if I can, uh … [A long beat.] come up with something else.

Peter: Eventually people just stopped tuning in, and in 1993, The People’s Court was canceled.

Kaye Switzer: And then one day, Sandi called me and she said, “Oh my God.”

Peter: This is Kaye Switzer. She worked on The People’s Court for more than a decade. And after the show was canceled, she and her producing partner, Sandi Spreckman, were looking for a new project.

Switzer: She said, “Oh my God.” She said, “I was watching 60 Minutes last night.”

Peter: In 1993, 60 Minutes aired a segment about Manhattan family court.

Switzer: And there was this fabulous judge from New York—family court in Manhattan.

Judge Judy: So your objection’s noted. It’s overruled. Have a seat.

Peter: It was Judy.

Judge Judy: No, no. Listen to me! This is not a tea party. You make an objection; I rule.

Peter: And the segment focused on Judy’s ferocious criticism of a court system that she saw as slow and painfully ineffective.

Josh Getlin: Manhattan family court was just this, uh, parade of dysfunction that just kept—it’s like a river that kept flowing.

Peter: Josh Getlin was a national correspondent for the L.A. Times, and he wrote a profile of Judy back then.

Getlin: Kids were just rolled in and out of the courtroom. You never quite got a sense that there was any follow-up. And every single judge was, you know, inundated with way too many cases to adjudicate on a daily basis.

(A rolling, roiling synthesizer arpeggio creates a sense of movement and urgency.)

Getlin: Judy was the only judge that I saw functioning in that building who was driven by something more than “Let’s get through the day.” She was driven by a real sense of anger and outrage.

Peter: Family court handles some of the most complicated and sensitive types of cases—cases involving family custody, child abuse, neglect, juvenile delinquency. And proceedings can drag on for months and months.

But not in Judy’s courtroom.

Getlin: I had never seen a judge that was as frank [Chuckles in one short exhale.] and unrestrained in her comments as to what she thought was going on in front of her.

Judge Judy: This is not a legal game, counselor. This witness may not have a terrific memory, but I’ve got a very good memory, sir.

Petri Hawkins Byrd: I remember when Judge Scheindlin would come in, she was so rapid-fire, man.

Peter: Petri Hawkins Byrd was a court officer assigned to Judy’s courtroom back then, and he’d go on to play the bailiff on Judge Judy.

Byrd: You really appreciated her because she was no-nonsense. They say “The wheels of justice grind, but they grind slowly,” you know. [Chuckles heartily.] No, we don’t—we don’t really have time for that! [Laughs fully.] You know? They must grind as swiftly as possible in order for everybody to get an opportunity at real justice.

Peter: But after more than 10 years as a judge, Judy was starting to feel like the courts were more broken than she was able to fix.

Switzer: We called her, in Manhattan, in her—her chambers.

Peter: So when TV producers Kaye and Sandi called her up in 1995—

Switzer: She said, “I’ve always dreamt about coming back in my next life as Judge Wapner.” And that was the beginning of it.

(A steady beat comes in.)

Peter: Once Judy was on board, Kaye started trying to find investors to put up the money for a pilot episode.

Lyttle: Judy reminded me of my mother.

Peter: Larry Lyttle was the only one who said yes.

(The music fades down.)

Lyttle: Now, she could only chronologically—likely—be my older sister, but she reminded me of my mother. She had that audacity that was, at times, you know … It created wonderment and, at other times, it made me insane. But she had that—she had that special quality.

And here’s something really peculiar. You know why I sensed that the audience could get back into the courtroom shows when nobody wanted one? Is because we had just gone through the O. J. Simpson trial.

NBCLA’s Chuck Henry: (Over a drumroll.) Now here’s the latest on the O. J. Simpson trial.

Nightline voice-over: For more than a year, it has been the center of the universe, a force of nature sweeping aside anything and everything in its path.

Peter: So the O. J. trial was happening. And suddenly, people couldn’t get enough of court TV. But—

Lyttle: They had this judge.

Judge Lance Ito: My apologies to you for the, uh, late starting time.

Lyttle: His name was Lance Ito. He kept dragging it and on and on and on.

Judge Ito: So I realize that we’re all tired and we wish this were over sooner than later. (Fades out.)

Peter: Everyone in the whole country was feeling the frustrations that Judy had been feeling in family court: American justice seemed slow, and unsure, and unsatisfying.

Lyttle: And there was no resolution for months, and people were tired of it. They hated the equivocation. They were exhausted by it.

We had somebody who had this larger-than-life personality in—in a diminutive 5-foot-2 stature who gave you instant fucking gratification and resolution with an opinion behind it. Home run!

(A soft, lightly dreamy pop synthesizer beat plays.)

Lyttle: The reason for the courtroom-show success, across the board, is because they offer instant—relatively speaking—instant resolution.

(A beat.)

Lyttle: So I said to her in the room, “Okay, I—I—I want to do it.” [Laughs in one halting laugh.] And they looked at me, and I was like, “Yeah, I want to do it.”

The genius of Judge Judy—the genius: When Judy saw two litigants that were really good, she shut up. And when she saw them they couldn’t handle it—which was most often—she took over. So now you had showtime. ’Cause the resolution, you know—who gives a shit if that fat kid, uh, you know, lost five grand to his pimply, uh, sister. Who cares?

So my formula was: It’s about her, and it’s only about her.

(Another beat of music, this time with a driving, bouncing bass line. After a bit, the music fades out.)

Switzer: The day before we were to shoot the pilot, I happened to say to Judy, “Judy, are you going to base your judgment on California law? Because we’re in California.” And she said, “No, uh, okay. I’m not.” And I said, “Oh, well, are you going to base your judgment on, um, New York law, then?” She said, “No, I’m not.” [Switzer laughs nervously.] I said, “Well, what are you going to base your judgment on? She said, “Judy’s law.” She said, “Common sense.” [Switzer seems almost incredulous.] Common sense!

(Bubbly, bright music plays, wistful and vaguely new age. A xylophone drives the melody.)

Peter: After years of being bogged down in a broken court system, as a TV judge, Judy would now have a lot more power to run her court the way she wanted to. And, actually, she would have more power than any American civil judge has.

Because Judge Judy’s court works differently than any American court.

When you go on Judge Judy, you agree to something called arbitration. Instead of going to court and standing before a judge, you let a single person called an arbitrator make a onetime, binding decision in your case.

And as an arbitrator, Judy had an enormous amount of freedom. I actually found a copy of an arbitration agreement used by the show. And in paragraph 4, it says that Judy, quote, “is not required to decide the claims,” meaning the cases on the show, “under the laws of California or the laws of any other jurisdiction.”

In other words, Judy was literally not bound by any specific laws in making her rulings. She was able to rely instead solely on “Judy’s law”: her idea of common sense.

(The music builds, then the melody drops out, then the sounds fade out entirely.)

Peter: And here’s how that would play out.

Peter: First of all, can you sort of give me sort of the—the background of, um, what sort of led to your case being filed?

Bruce: Uh, yeah. So I get the call very last-minute. I’m a … (Fades under.)

Peter: This is a guy I’ll call Bruce. He asked us not to use his real name. Bruce provides equipment for concerts and events. And, a few years ago, he did a job for someone, and he got paid with a check.

Bruce: Monday, I go to the bank and I said, “Is this check good?” And they just said, uh, “Not at this time.” I started going daily to the bank, and every day, there was just not enough money to cover it.

Peter: So Bruce tried to get in touch with the guy who had written the check.

Bruce: And no answer. Left him a voicemail saying, “What’s up? The check’s no good!” And I kept calling. No answer. So I filed small claims.

Peter: But small-claims court can be a bit of a nightmare, actually. For one, it’s often hard to, like, physically locate the person you’re trying to sue and get them in a courtroom. And even if you do that and you win your case, there’s still another potential snag.

Byrd: You have a judgment in your favor. But [Chuckles.] that don’t mean jack. That don’t mean jack.

Peter: This is Bailiff Byrd again.

Byrd: Even if you win in your local jurisdiction, you still have to collect. Therefore, your judgment means jack bubkes to somebody who’s hiding from you or not willing to pay the judgment anyway!

Peter: So often people never end up seeing their money, and the whole thing becomes a big waste of time. And Bruce had been there before.

Bruce: I’ve been in small claims multiple times already, so I knew the game very well. And two days later, I get a call from a guy who said, “I’m a producer for Judge Judy. And would you be interested in settling this on TV?”

(Really bright, wobbly, round music plays, plodding along steadily under Bruce’s story.)

Peter: When Bruce filed his lawsuit, it automatically became public record. Like, that’s just the way that small-claims court works. And so a Judge Judy producer was able to find his information and reach out.

Bruce: And I said, “Well, I don’t think you’ll even be able to get in touch with him.” And he said, “Well, do you have a phone number?” I said, “Yeah, I got his number.” And he goes, “Well, if you got his phone number, I can almost guarantee you, he will come on the show.” I was like, “Okay. Prove it.” The next day he calls me back and he goes, “Yep, he’ll be on.” And I’m like, “No way!” My—my jaw hit the floor.

Peter: Bruce was a local. But for litigants who lived far away, the show would fly them out to California and put them up in hotels so everyone would actually show up for the hearing.

And here’s the real kicker.

Byrd: The big selling point has always been: If you win your case, the show will pay you.

(The music plays out.)

Peter: All of the money on Judge Judy came directly from the show. So if you won your case, the show would write you a check and put it in the mail.

Bruce: And then I learned all of that, and I was like, “No wonder everybody wants to do this!” You know, it’s very logical, because they pay for everything.

Peter: Bruce was in.

(Rock music enters.)

Judge Judy: You promised that you would pay them. A nominal amount—but that you would pay them.

Voice-over: Did he take the money and run?

Judge Judy: So why didn’t you pay him?

(The music fades out.)

Bruce: And as we walked in, she’s scowling at him, and I’m like, “Oh, this game’s over already.

(Back to the show.)

Judge Judy: So you owe them, so far, $2,400.

Defendant: Correct.

Judge Judy: So why didn’t you pay him?

Defendant: Because I was depending on the … (The show audio fades under.)

Bruce: And as soon as she started asking us questions, she just turned into Judge Judy like usual—and very snappy.

Judge Judy: No, don’t tell me what they knew. I didn’t hear that that was part of the discussion.

Peter: I reached out to the defendant in Bruce’s case, but he never responded. In the episode, he doesn’t really present much of a defense, but insists that he shouldn’t have to pay. And Judy wraps up the case in about 10 minutes.

Judge Judy: Right now you owe him $2,400. Judgment for plaintiff. We’re done.

Byrd: Parties excused. Please step out.

Bruce: I wish, uh …

(The exit music plays, then fades out. The show clip ends.)

Peter: So how was—how was your experience in Judge Judy’s court? How did that compare to all your experience in actual small-claims court?

Bruce: Well, this was lovely. It would have been hard for me to get that guy to show up in small claims. This was instant. They paid me within a month. It was exactly what I asked for. So …

Peter Bresnan: Would you ever, um, would you ever go on the show again?

Bruce: Without any question! Heck yes, I’d do that again.

(Sparse music, like stars in outer space, plays for a brief flourish: a melody in a void.)

Peter: At the end of the day, Bruce got the money he was owed at a speed that a real court couldn’t even compare to.

Makita Bond: I feel like there’s no justice in the court system.

Peter: This is Makita Bond. She was a producer who worked on Judge Judy.

Bond: The actual court really doesn’t care about you. So the plaintiff has to do all the work, but then, when they win, they don’t even get anything. It makes no sense, you know, for a plaintiff to go through all that stuff just to not get paid.

Peter: Right. So it’s like Judge Judy is almost a better chance at getting something like justice, than going through—

Bond: Any court show, any court show.

Peter: Really? Hmm.

Bond: Absolutely. Because, like, everybody gets something out of it. So I just—I just feel like there should be more court shows. (Laughs.)

(A stirring sound, a string instrument played over the hum of a forest late at night, insects cacophonous and everywhere.)

Peter: Judge Judy is almost like this parallel version of the court system that is free from all the bureaucracy and delays and uncertainty that are often a part of the real-world court experience. And if your actions fit into Judy’s definition of common sense, then you are guaranteed some level of justice.

(A long beat—the height of Peter’s optimism—plays as the music pitches up.)

Peter: The closer you look at Judge Judy, though, the more that idealized version of justice starts to fall apart.

Byrd: There’s a bit of a deception there. You know, it’s a well-intentioned deception, but is deception, nonetheless.

(The bottom drops out as the music pitches down.)

Longoria: After the break, the other side of Judge Judy.

(The music settles into itself for a long moment, then fades out into the break.)

(Echoes of Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 5” play on a distant piano for just a moment before the episode resumes.)

Longoria: I’m Julia Longoria. This is The Experiment. We’re back with producer Peter Bresnan and the beauty—and, perhaps, the horror—of his family’s favorite TV show: Judge Judy.

Peter: As I was trying to understand how Judy Sheindlin thinks about crime and punishment, and why she made the kind of decisions she did, I came across this book that Judy wrote back in the 1990s. It’s called Don’t Pee on My Leg and Tell Me It’s Raining—which is just objectively an incredible name for a book.

In the book, Judy lays out this worldview that she developed during her time in court.

Getlin: If you had to sum up her mission in one clear phrase, it would be: “You have to take responsibility for your actions.”

Peter: Josh Getlin, the journalist who wrote a profile of Judy back when she was a judge? He actually co-wrote this book with Judy.

Getlin: And that became kind of like a theme for her in everything she did. She was never one to say, “Well, there are outside forces.” She looked hard at the individuals who came in front of her every day. It wasn’t just that, you know, she was worried sick about the—the conditions of a court system that wasn’t functioning. She was really angry that people were responsible for that dysfunction.

Judge Judy: It seemed to me, bureaucrats weren’t doing what they were supposed to be doing … (Fades under.)

Peter: This is from an interview that Judy did on Roseanne Barr’s talk show in 1998, in which she talks about her time in court.

Judge Judy: I got tired of listening to excuses.

Roseanne Barr: Mhm.

(Slow, almost out-of-sync and discordant electric guitar passes over a lazy horn line: a sad and empty song.)

Judge Judy: You know, “I grabbed the old lady’s pocketbook and I threw it down the stairs because my grandmother died.” I said, “Listen, I lost my grandmother. I was sad. I cried. My grades went down a little bit, you know, but my reaction wasn’t to go and sell two kilos of heroin or”—[Audience laughter.]—“or to throw in an old lady down the street.” And so I swore to myself … (Fades out.)

Peter: In her book, Judy wrote that there was a broader breakdown happening in American society—and the cause of that breakdown was a widespread lack of “personal responsibility.” She wrote, quote, “Somehow we have permitted irresponsible behavior to be socially acceptable and have set up an elaborate bureaucracy that encourages lack of individual responsibility.”

Judy tells a series of anecdotes from her time in court to justify this worldview. She writes about what she calls “crack mothers,” about welfare scammers, about people having more kids than they can afford, and about what she calls a, quote, “new breed” of violent juvenile delinquents. She imagines a world in which there are more jails, harsher sentences, and fewer rehabilitation programs.

(A beat of music.)

Peter: I wanted to ask Judy about all the claims she makes in her books. She declined to do an interview for this story, and didn’t respond to requests for comment.

But for me, personally, I found a lot of the book to be pretty disturbing, to be honest. On one level, it is just rife with the kind of racist, classist stereotypes that were really prevalent in the ’90s. And, more than anything else, the book shows a complete disregard for any of the structural causes of inequality. Like, for Judy, the concept of being disadvantaged is in itself a kind of excuse.

In her second book, which is called Beauty Fades, Dumb Is Forever, Judy writes, quote, “I know that this view is controversial, but I believe victims are self-made. They aren’t born. They aren’t created by circumstances. There are many, many poor, disadvantaged people who had terrible parents and suffered great hardships who do just fine. Some even rise to the level of greatness.” She says, quote, “If you decide to be a victim, the destruction of your life will be by your own hand.”

Victoria: Hmm.

Peter: I read that quote to my mom.

(The music fades out.)

Victoria: That’s beau—I think that’s a great quote. Yeah, well, we’re all, you know, we’re all—what’s that expression that—“the writers of our own destiny,” on some level. Um, it’s also really easy for someone like me to say that when I have not had to experience racism or, um, sexual abuse or poverty. You know, I never had to experience any of those things. So it’s easy for me to say, “Oh, everyone can rise up.” But I think that’s the premise to her show, is that, you know, if you take responsibility, if you try and, you know, work hard and—and do the best you can do, you can do better than this.

Peter: It is important to point out that these books are more than 20 years old. And Judy has actually said in a more recent interview that her views on crime have developed and expanded over the years, although she hasn’t specified exactly how they have expanded.

But now, when I watch Judge Judy, I hear all these echoes from Judy’s books.

Judge Judy: I mean, the way people get out of poverty is not to say, “Well, I’m poor. I think I’ll go have another baby.” Ridiculous. (Audience laughter.)

Peter: She often berates people for having too many kids, or goes after people who are on disability who she doesn’t think should be on disability.

Judge Judy: That’s not disability. That’s not what disability is for.

Peter: She calls out alleged welfare fraud when she sees it.

Judge Judy: And you also lied to the welfare department and to the state. So maybe now the state will come back and say, “You know what? We want you to pay back the money that we’ve been giving to you the last five years and go get a job.” That would be a nice thing to do.

Peter: And of course, she talks a lot about—

(A montage of clips.)

Judge Judy: Responsibility. [Underscoring and emphasizing once more.] Responsibility.

Judge Judy: That’s part of what we call responsibility

Judge Judy: When you do something wrong and when your kids do something wrong, you’re supposed to take responsibility. You’re not supposed to cover it up. That’s not … (Fades out.)

(The montage ends.)

Peter: On the show, Judy seemed to make it her mission to make people take responsibility for their bad choices.

(Another montage.)

Judge Judy: (Emphatically and loudly.) You are going to pay her!

Judge Judy: You owe her $2,000. [With force.] Pay it!

Judge Judy: He gets his money back from you.

Judge Judy: (Yelling each word, staccato.) You have to pay her!

(The second montage ends.)

(A dreamscape plays, with a low tripping beat and chords that are sustained across space.)

Peter: But is that what was actually happening on Judge Judy? Were people being forced to take some kind of responsibility?

(A beat.)

Peter: So, for someone going on Judge Judy, the biggest selling point is:

Byrd: If you win your case, the show will pay you.

Peter: But the flip side to that is, if you’re a defendant—if you’re the one being sued on Judge Judy—and you lose, you actually don’t have to pay anything. The show pays the judgment for you.

Byrd: The defendant can only win. That’s in a win-win-win situation. And I don’t think people understand that. You know, there’s a bit of a deception. It’s a well-intentioned deception, but it’s deception nonetheless, because if there is no penalty that the defendant has to pay, then the defendant can’t lose.

(Another beat. A quiet electric guitar begins to play.)

Peter: There is a small block of text that shows up at the end of every episode of Judge Judy, explaining that all the money comes from the show. But I had never seen it, and even the most avid Judge Judy fan I know had never seen it.

Victoria: I like to believe that, you know, the person that her decision is against, you know, has some kind of repercussion or responsibility for—for that judgment.

Peter: This is my mom.

Victoria: ’Cause, you know, it doesn’t seem right. Actually, you know, I mean, if you owe somebody money and then the court just pays it, what—what kind of responsibility or repercussions or consequences are you really [A breath.] getting, you know?

(A long moment of music.)

Peter: After speaking to multiple former litigants, I learned that even though no one has to pay any money on Judge Judy, going on the show can still can have real repercussions and real consequences.

(The music fades out.)

Peter: So this is a guy I’ll call Andy.

Andy: I’m a bar manager in, uh, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Peter: And back around 2007, Andy was in his early 20s and living with a friend of his I’ll call Jonathan.

Jonathan: It was a two-bedroom apartment in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Peter: We changed both their names to protect their privacy.

And one night, Andy and Jonathan got into a fight.

I should say that both of them tell radically different stories about what happened that night. There was probably some alcohol involved, and maybe a bath mat soaked in cranberry juice? Anyway, what they both agree on is that, at one point, they were outside the apartment …

Andy: We got into an argument, and he shoved me.

Jonathan: I got up. I pushed him.

Andy: I had a drink in my hand.

Jonathan: He threw a collins glass directly at my face.

Andy: And I smacked him over the head.

Peter: Andy broke a glass over Jonathan’s head, and gave him cuts all over his face.

Andy: Which I completely regretted immediately after I did it. You know, you don’t really want to hit your friends.

Peter: Andy remembers trying to reconcile the next morning. But Jonathan says their friendship was effectively over.

Jonathan: And it was me just moving out pretty much immediately.

Peter: And then almost a year goes by. Andy and Jonathan have no contact whatsoever.

Andy: And then I get a call from a producer. And she says, “Hey, he wants to take you to Judge Judy.”

(In waves, over a steady bass line, electronic chords ring out.)

Peter: Jonathan initially wanted to take Andy to small-claims court for his medical bills. But Andy was just a server, and he didn’t earn a lot of money.

Jonathan: So I wasn’t going to get anything that route. And I was told by a family friend that, you know, in the event we were to go on that show, it would be the show that actually would award what I knew he couldn’t pay.

Peter: Had you ever seen Judge Judy before?

Jonathan: I had seen it a few times. I thought of all the shows that were out there, she was the most serious and would treat it, uh, [Chuckles.] seriously.

Andy: I—I didn’t want to do it. I told the producer no at first.

Peter: Andy says he tried to talk Jonathan out of it.

Andy: I called him multiple times and said, “We shouldn’t do this. And I’m not—I’m not down with that. These—these shows are—are meant to humiliate people and profit from that humiliation.”

Peter: And, at the same time …

(The music fades away.)

Andy: This producer, uh, was telling me that I should come on this show ’cause it’s gonna be a great time. And she kept calling. She kept calling.

Peter: I reached out to that producer. She didn’t respond to requests for an interview.

But I’ve spoken to multiple former Judge Judy producers. And it’s clear that a big part of the job was persuasion.

Mike Kopplin: We’d do everything from we’d keep calling, we’d send letters, we’d send a pizza with a—a note attached to it.

Peter: This is Mike Kopplin, another former producer on the show.

Peter: You would send pizzas?

Kopplin: Yeah, we—So we would call, like, a pizza parlor in their local place, like a Domino’s in their hometown. And we would fax the—the Domino’s a letter, and then say, “Could you, you know, take that on and deliver this pizza to their house?” ’Cause we know that they’ll answer the door for a pizza. If they won’t answer our phone calls and everything like that, but they’ll answer the door for a pizza, and then they’ll get our letter at least. And we’ll be like, you know, “Please just give us a call. Let’s work this out.”

Peter: So Andy was getting all these messages from a Judge Judy producer. And he decided to get a second opinion.

Andy: So I called the attorney and I got his advice. I’ll never forget when he said: “Listen, man, here’s the deal: If I were you, I’d just do it. Just, uh, kind of swallow your pride and do it. Because, uh, this will become a bigger thing. You could wind up at civil court owing this guy a couple grand.” So I felt like, between what that attorney had told me, um, and what the producers had told me via voicemail calling me, email me, texting me, all that stuff—I felt like I didn’t have a choice.

(Funky, wobbly, bright music plays.)

Andy: So I go. And they fly me out to L.A., and they did put me up in a sort of a swanky hotel right there on Sunset.

Peter: It’s taping day for Andy and Jonathan’s case.

Andy: They have a car come pick me up in the morning, and, you know, we’re going to the green room, and the producers are telling me to just hype it up as much as you can. I mean, picture a coach, you know, trying to get you hyped up before, uh, before the Super Bowl.

Kopplin: And that’s 90 percent of a producer’s job, is to just go in and you just keep going [Clapping for each “over.”] over and over and over and over. You dump Red Bull into all the guests before they go in so that they—their energy is up and they’re—they’re pumped and excited.

Andy: “I need you to hype this up. You know, this guy is your enemy. This guy is going to—he’s going to take you down. We have to—you know, we’re working with you. We’re working together.”

(The music takes an ominous turn, with a low drone overtaking the wavering guitar line.)

Peter: Then, Andy and Jonathan are on the Judge Judy set.

Jonathan: I’m walking through the set, and there’s this audience in the crowd and there’s people sitting there and then, behind them, there’s all these cameras that are just built into these walls. You know, I certainly felt the sensation of stage fright.

(The music fades out.)

Andy: I just kind of felt like, “Tell your truth; tell what happened. Don’t lie about it. And, uh, you have nothing to be ashamed of outside of regretting hitting your friend for doing something incredibly stupid.” And, uh—and honestly, I—I feel like she respected my, uh, my candidness. And fortunately, you know, Judge Judy just kinda agreed with—with everything I was saying.

Peter: And then, the case takes this bizarre turn.

Judge Judy: I don’t have a doctor’s report here. All I have is this. (The sounds of a paper being flattened out.)

Peter: Judy asks for a medical report.

Judge Judy: So you didn’t go to the doctor with regard to these cuts on your face. You went with regard to something else.

Jonathan: Um, that was the first thing that I had addressed.

Judge Judy: You … ?

Jonathan: I went for—I addressed multiple things while I was there.

Peter: Jonathan told me that, when he went to get the cuts on his face looked at, he also asked the doctor to look at a spider bite he had on his thigh.

Jonathan: And she says, “You didn’t go to the doctor because you had these cuts on your face—”

Judge Judy: You went there because you had a lesion on your groin. [The paper ruffles. One single person gasps loudly, but from a distance, in the courtroom audience.] That’s why you went to the doctor on June 11th. Not because of what was on your face. You also spoke to him about it, but that’s not why you went to him, because you had been treating that yourself for 11 days with Neosporin. [The paper ruffles again.] That’s why you went to the doctor.

Jonathan: And I was just so dumbfounded. Like, where did this come from? [Incredulous.] What? What just happened?

If you pause the show, a clip of the actual show, when you paused it, you could see that the medical records actually said “spider bite.” And that is where this is just so ludicrous, that something like that would be turned into, “You had an STD.”

To turn the case of assault into what it was turned into, it’s asinine. And no judge, nowhere, would have ever said that in the courtroom

Peter: By the way, in the arbitration agreement I found, it says that litigants waive the right to sue Judy over statements they feel are false and defamatory. So Judy can really say whatever she wants.

Jonathan: The entire thing from start to finish was, um … There was no justice. There was nothing that was fair about that situation.

Peter: In the end, Judy awarded Jonathan about $1,200, which, of course, Andy didn’t have to pay.

Peter: What did it feel like to watch the episode?

Andy: Initially, vindication. [Hesitating.] Followed by—I mean, within seconds, followed by extreme regret and disappointment and sadness.

And I felt so sorry for my friend that just—just made that very poor decision. These shows are—are exploitative because they prey on poor people who think that they might be able to get some money from this show. At the cost of—nothing’s free—at the cost of some level of self-respect.

I just wish he hadn’t done it. [Starting to stammer.] I just wish we could have—I—I … Obviously, I—I—I apologized to him a thousand times, but … It’s, um … He made a mistake with the Judge Judy thing.

(A warm drone begins to loll about underneath the narration.)

Peter: We reached out to CBS Media Ventures to ask about the tactics producers used on the show, and about the terms of the guests’ participation. But they didn’t respond to a request for comment.

(A beat.)

Byrd: There’s a saying that the judge used to have all the time, that—that I always took umbrage with.

Peter: As the bailiff on Judge Judy, Petri Hawkins Byrd was mostly a silent presence. [A beat.] But he had the chance to observe Judy try literally thousands and thousands of cases.

Byrd: She’d—she’d say, “It doesn’t make sense. And if it doesn’t make sense, it isn’t true.”

(A clip from the show.)

Judge Judy: (As papers ruffle.) I’m not quite sure about her story.

Unidentified voice: Okay.

Judge Judy: It all doesn’t make sense to me. If it doesn’t make sense, it’s usually not true.

(The clip ends.)

(The music dissipates.)

Byrd: The vision that Judge Judy presents is that of an all-knowing, all-seeing arbiter. The reality is that there’s a reason that they call them “hearings.” All the evidence has to be heard. All of the testimony has to be heard. In its fullness.

I’ve never doubted, uh, in Judge Judy’s ability to know the law.

But justice, unfortunately, isn’t all about the law. It’s about the circumstances—it’s about the nuances of any particular case.

If you see Judge Judy in action, you’re like, “Wait a minute. Suppose I don’t get to bring out this certain point or suppose she finds this point irrelevant or suppose she just thinks, in the back of her head, that I’m lying. Then [A beat.] I got nothing. I got nothing. And I can’t go back and appeal it.”

Okay. If—if I’m standing there and she calls me a moron who has on an ugly suit that’s offending her, the only thing I can do is stand there and take it.

If I tried to interrupt and bring forth a point but then she doesn’t listen to it, what then? Now I’ve lost my case, [Chuckles lightly.] I’ve lost my dignity, [Laughs.] and I’ve lost the opportunity to appeal the case and bring it before another magistrate who I might feel will be fairer in listening, you know? I mean, I’ve—I’ve stood there and witnessed cases where the person got shot down and never said anything. [Emphasizing.] Never said anything!

Peter: After months of digging into Judge Judy, I called my mom again. At the risk of ruining her favorite show, I told her everything that I’d learned about what goes on behind the scenes.

Victoria: You’re not supposed to know all that stuff. It’s—it’s—it’s for—it’s entertainment.

Peter: I think it’s fair to sum up my mom’s reaction as: “Eh.”

Victoria: There’s a part of me that it—it rubs me wrong that they—they kind of get away with not having to have the financial consequences of having a ruling against them. But I like to look at the bigger picture and see that they’ve gone on a—a TV show, showing their true colors in front of 10 million people. Now 10 million people know who they are.

Peter: Hmm.

(A beat.)

Victoria: What’s your opinion? Have you changed your opinion?

Peter: Of Judge Judy?

Victoria: I know that we’re off-topic here for some—a second.

Peter: No, no, no! I am not sure how to feel exactly.

(New music: an ethereal buzz, resonant notes humming in a golden void.)

Peter: I get my mom’s argument. At the end of the day, Judge Judy is entertainment. It’s just a TV show.

But I also think that, for some of the people who went on Judge Judy, it wasn’t just a TV show. They sincerely believed in the show’s capacity to give them the resolution that they couldn’t find anywhere else.

So was Judge Judy able to provide people with real justice?

(A beat.)

Peter: I think the answer to that question just really depends on how you define justice. Like, if you think justice means getting some money that you’re owed at a terrific speed, then I think that Judge Judy was very effective at providing justice to people.

But if you think that justice requires due process, and hearing all the evidence and testimony in its entirety—if it requires respecting the dignity of every person involved in the process—then I think Judge Judy fails utterly to provide justice.

(Another beat.)

Peter: To me, justice is not the same thing as one person’s gut feeling.

(The music fades out.)

Byrd: America and the rest of the world came to view the Judge Judy, courtroom experience as the quintessential courtroom experience. It is, uh, deceptive to the point where people may not realize that—that that’s not exactly the way civil court is conducted.

And some people in other countries are looking and going, “That’s the way it is over there? That’s that—that’s how y’all handle it?” You know? “That’s your ideal of justice?” You know?

And then some people here think, “Yeah, yeah! That’s—that’s the way it should be. That’s the way it should be!” You know, a judge should just look at ’em and tell ’em, “Get the hell out of my courtroom! You’re an asshole.”

[Quickly, to dissuade this imagined counterpart.] No, no, no, no, no, no, no! [Laughing lightly, but with a kind of seriousness, too.] That’s—that’s not how—That’s not the answers that we seek from those that we seek to—to dispense justice. That’s not how—that’s not how that goes.

(A sonic drop in a quivering bucket, an underwater kalimba that causes headphones to break out in static: low, peaceful, solemn.)

Peter: Judge Judy wrapped in 2021, after more than 6,000 episodes. But Judy didn’t stop trying cases. Almost immediately, she started a new show on a new network with the same premise: It’s called Judy Justice.

(Sounds accumulate in the bucket. From far away, a chorus sings indistinctly. Then it leaves, taking the bucket and all its noise with it.)

(For the credits, after a beat of quiet, a new song. It’s another dreamscape, lazy and lush and a little sad, like the feeling of a sunset that indicates the end of the day, coming sooner than you wanted it to. Golden, but a little sad.)

Victoria: (With a staticky quality that indicates this was recorded over the phone.) This episode of The Experiment was produced by my son Peter Bresnan with help from Salman Ahad Khan. Editing by Jenny Lawton, Julia Longoria, Emily Botein, and Michael May.

Fact-checking by Will Gordon. Sound design by Joe Plourde with additional engineering by Jennifer Munson.

Music by Tasty Morsels and Alex Overington.

Our team also includes Alyssa Edes, Tracie Hunte, Natalia Ramirez, and Gabrielle Berbey.

Special thanks to Sean Bresnan, George Ramirez, Judge Billie Colombaro, and Mychelle Vasvary.

If you enjoyed today’s episode, please take the time to rate and review us on Apple Podcasts, or wherever you listen.

The Experiment is a co-production of The Atlantic and WNYC Studios. Thanks for listening.

(A breath of music.)

Longoria: For our listeners who don’t know, this is actually Peter Bresnan’s last week with The Experiment. And so we’ve asked his mom on to just talk about how wonderful he is. So, um, why don’t you just tell us a little bit about the wonders of Peter Bresnan?

Victoria: Well, I can’t say enough good things—and I’m not just saying that because I’m his mom.

Longoria: (With a sweetness.) Hmm.

Victoria: Peter is an extraordinary human being. He, um, is kind, he is empathetic, he’s compassionate, he’s intelligent. He is talented. Whether it be his podcast, his knitting sweaters, or baking pastries [Longoria chuckles.] or his, uh—his dedication to his friends, he is just an all-around incredible human being. And just so honored that—that, uh, you know, he’s part of my life. And, um … I—I just adore him! (Both chuckle lovingly.)

Longoria: Well, we were so honored to be his co-workers. Peter handles the work with grace and empathy and care and, uh, I will miss working with him. And I’m sure it won’t be the last time we work together! Thanks, Peter.

(A beat of music, a flourish, and then …)

Victoria: Well, one other thing that you need to say is that he’s an awesome cat-dad to Moose.

Longoria: (Laughing heartily, followed by Victoria’s laughter.) I have no doubt! I’ve met Moose on—on Zoom, and Moose is thriving.

Victoria: Yes! Yes. It’s all about Moose!

Copyright © 2022 The Atlantic and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.