On the Inside Looking Out

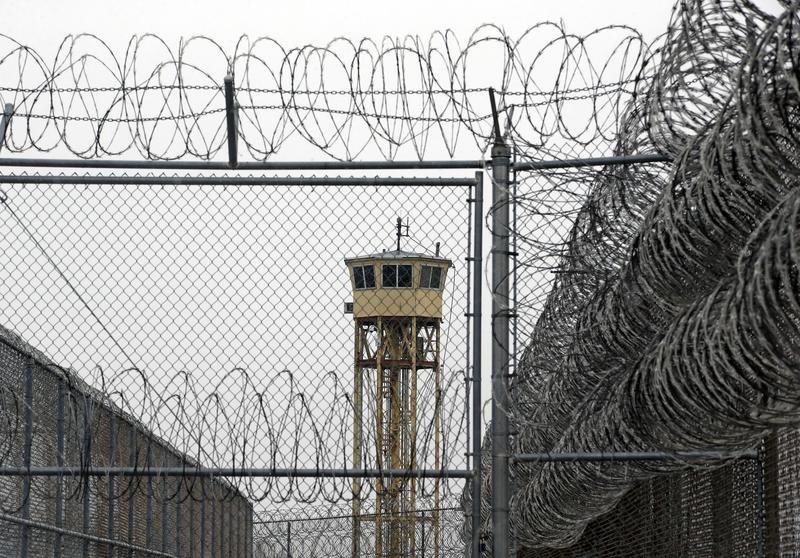

( AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, Pool, File )

BROOKE GLADSTONE As Solomon said, news outlets who don't regard incarcerated people as part of their audience may be reluctant to retool their lexicon, but people in prison are reading the news to the extent they can. While most of us are lately awash in a news cycle dense with infection data, vaccine updates and public officials trying to balance fatigue, facts and safety, incarcerated people are cut off from that deluge. Offered instead merely a trickle. John J Lennon is one such reader who finds himself in everlasting pursuit of information. He's also a journalist who's written about prison life under COVID in the New York Times magazine. He's a contributing writer for The Marshall Project, contributing editor at Esquire and an adviser to the Prison Journalism Project. He's also serving an aggregate sentence of 28 years to life at Sullivan Correctional Facility in New York that accounts for the quality of the line.

JOHN J LENNON So I am in the belly of the cell block and I'm calling you on one of four phones.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You've been at the Sullivan Correctional Facility in New York for 19 years, right?

JOHN J LENNON That's correct. I mean, for a couple years you're on Rikers Island fighting the case. And I was convicted and sent up.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Have you challenged the verdict?

JOHN J LENNON No, I'm guilty. I've killed a man. I was a drug dealer. I was in my early 20s, and I take full responsibility for what I did.

BROOKE GLADSTONE When did you start writing?

JOHN J LENNON I learned how to write in a creative writing workshop, in Attica in about 2010. This professor came in from Hamilton College and he volunteered to teach a creative writing class and kind of just stumbled into the class and just took to it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So there's a scene in an article you wrote in February about getting the Sunday edition of The New York Times. You subscribe to the actual print edition and you say you love the texture and the smell, but it's expensive. And so there's a literal line in your cell block to read it after you're through.

JOHN J LENNON New York Times is pricey when you subscribe to it. So I pass it on when I'm done. So that's just the line of guys, you know. Let me get it after you. Let me get it out to you, that kind of thing. Some guys get a little disgruntled when I pass to somebody before, you know, it goes by seniority who has been here. I try to let them work that out amongst themselves.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Could you describe what news consumption is like for people in prison?

JOHN J LENNON There is a kiosk and there is an online, I think Associated Press, they have. Depending on what prison you're in, some prisons have TVs in their cells. Sullivan Correctional Facility where I'm at does not have TVs in there. So we mostly get our news from NPR or periodicals. This is a big radio jail. So if you're going to get news, you're gonna get it from NPR.

BROOKE GLADSTONE [LAUGHS] NPR is popular?

JOHN J LENNON It is. Brooke, I'm a big fan of yours.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Now, Public radio obviously is not always right. It hasn't always been right about the pandemic, but there's a serious effort to try to be right. And I just wonder whether people consuming different news sources within the prison have debates over, say, the efficacy of vaccines.

JOHN J LENNON You know, it's a good question. You take the vaccine. I think people on the outside kind of want to know what's going to happen with their travel restrictions, what's going to happen with their local gym. They want to know what their life's going to look like. I think the same goes with folks in prison. They want to know, are they going to be able to hug their family on a visit. They want to know, are they going to be able to attend the family reunion program where wives can come up? If I don't get the vaccine, am I going to be prevented from seeing my family? So that's really not being conveyed. To be fair to corrections, the judge just ruled and that we all get vaccines, so hopefully there'll be a campaign where they can give us some information so we could sort of see what our life would look like and make informed decisions, whether it's or not to take the vaccine.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You had mentioned that the final call, the newspaper of Louis Farrakhan's Nation of Islam, has been very skeptical of vaccines and that view has gotten around.

JOHN J LENNON Yes, some of the fellows do subscribe to that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Do you remember what the headlines were?

JOHN J LENNON Yeah, we don't want your vaccine and big pharma, big money, big fears. Understandably, the African African-American community has good reason to be skeptical about government studies.

BROOKE GLADSTONE How about your family on the outside? Are they skeptical?

JOHN J LENNON My mom lives down in Florida. Look, I'm not out there. You know, I'd be pretty persuasive if I was with my mom, but I'm not. I'm over a prison phone and people are in her ear, so she doesn't want to take it. I mean, you know, I don't want it. They should give it to you. And she's saying, you know, I think they shot water in that Joe Biden's arm. And then my aunt, you know, comes to visit her. And it's a cast of characters, even when I'm calling home. You know, my aunt's a fan of Trump and I'm just I'm trying to navigate this over a prison phone. And I'm like, stop it. Don't listen to Marianne and just take it. And it's difficult.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You mentioned how expensive The New York Times is. What is the cost of information, good or bad? Family and friends can serve as links to the outside world, but even talking to them isn't free. In your article, you highlighted a prison communications firm, a private firm, right, called Securus Technologies.

JOHN J LENNON Look, yes, I understand it's a controversial issue. So it's a private contractor. It comes in, makes deals with the state and it has deals with plenty of states, and now they have phones and now they have this new technology. They own the company, JPay, where they have these tablets. We can send emails, 30 second videos from family. You know I haven't seen my mother, she has Parkinson's. I really enjoy those videos. I could cut and paste on an email I was never able to cut and paste and I could use email. So, I mean, I'm a journalist, it helps me. So I'm kind of a fan of the program.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But there's no Internet,

JOHN J LENNON But no Internet, correct. They charge you for each email. They've come under scrutiny for this. But, you know, when you are using a Walkman and a typewriter for 20 years, I've been in prison close to it. You're grateful when you get some technology. I mean, I thumb-tapped much of this piece for The New York Times magazine using JPay

BROOKE GLADSTONE Securus Technologies provides JPay this access to the tablets. It also owns phone contracts for a lot of prisons and county jails and charges can go as high as 14 dollars for a 15 minute call. But downloading your mom's 30 second video only costs a buck, right?

JOHN J LENNON Yeah. The thing about those contracts, certain states and certain counties, they allow that. The public sector is culpable here, right? New York state prisoners won a lawsuit so they can't really charge us that much. But other counties and states, they do. So there's probably just as much culpability on those elected officials.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Securus, when it comes to phone service, is really cashing in. I thought it was surprising, though, that you argued that these tablets are actually a reason, at least for now, to keep for profit companies invested in the prison system.

JOHN J LENNON I did argue that. I mean, I appreciate the tablets. I of course, I don't appreciate other incarcerated people being charged 14 dollars for a 15 minute phone call. I think it's absurd. I think it needs to stop. In terms of the tablets here in New York, I think the program has some issues, but in totality it is an added benefit, and it enriches the quality of our lives.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Tom Gores, the businessman whose private equity firm owns Securus, was called upon by an advocacy group called Worth Rises to divest from the company Worth Rises opposes any private companies profiting from incarceration, and it put an ad in The New York Times saying: If Black Lives Matter, what are you doing about Detroit Pistons owner Tom Gores? And the ad called him a prison profiteer. Has Mr Gore's ever responded to the controversy?

JOHN J LENNON He acknowledged that is a controversial thing and it probably should be taken up by nonprofits. But guess what? Nonprofits don't have the infrastructure to do it. So if big bad Tom Gores is not coming in here offering us technology, I'm still typing on my typewriter. Right? I'm still listening to my Walkman. I mean, I'm in I'm in the 80s over here. [BROOKE LAUGHS] The government's not doing it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So you're saying there is no operating alternative to JPay right now?

JOHN J LENNON No, there's not. Look, I wish I could read The New Yorker online. The Atlantic online. You have to get that stuff? People take snapshots of great articles and then send them as pictures on JPay, so I could get the message in real time. Or, alternatively, they can make a copy and put it in the mail, or else I just subscribe to the print edition. But not everything online, as you know, appears in print.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But you're lucky because you have family and friends who can support you in this way and materially.

JOHN J LENNON Yeah, I mean, I'm self-sufficient. I earn my own income with journalism. I'm very grateful for that. I mean, it's a nuanced situation, right? You really can't have a bank account. The Son of Sam law in New York says you cannot profit from your crime in writing about your crime. The exception for the Son of Sam law is earned income, though. And I earn my income through journalism. And any time that I extensively write about my crime, I've donated that money to nonprofits, usually doing criminal justice work.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Beyond JPay, is there something advocates or lawmakers should be considering when figuring out the access to information that inmates can and should have?

JOHN J LENNON You know, who's it on, right? Is it on the public sector or the private sector to offer that? I wish that instead of AP that I could download online Atlantic articles or online New Yorker articles. I mean, I think that's on the provider, but that's also on some of the magazines to sort of get past, you know, let's be honest, they're kind of rough reputation that Securus has. But then guess what? We don't have that information. Right? So it's a really, really thorny issue.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What are the stakes here? I began with the anecdote in your piece in The Times about people lining up for the times. But does there seem to really be a hunger? Would it help them in prison? Is it something that is really worth paying attention to among so many other things?

JOHN J LENNON Absolutely. You know, I am where I am today because of access to the magazines that I mentioned. I learned how to write in that creative writing workshop at Attica, but I would still, over these feature magazine articles and reverse engineer them and like, really, really wonder how, like, these writers do what they do. That's because my mom subscribed to these magazines and I was privileged. Unfortunately, a lot of folks don't have that extra money. Yeah, of course it's important. But these are private corporations too, these media companies, right? So I think the question is, how important is it to them to get us the information? They have a lot of gorgeous writing online that I wish my peers can read. Sometimes, I don't want to give up my New Yorker magazine because I have these sentences underline. I don't want to give up my Esquire magazine. I don't want to pass that on. We started in this interview, we went down a road of questioning the ethics of Securus, but a lot of money being made in the media in America. Maybe it's a question we need to put on these companies. I mean, some of them are colleagues, some of the editors and chiefs of these places. I actually thought about writing an open letter to Jeffrey Goldberg and David Remnick and saying, hey, you know, make a deal with Securus. Let us read The New Yorker, let us read The Atlantic. That really helped me as a human being to read such gorgeous writing and important reporting.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In a piece earlier this month, you wrote about skepticism of the vaccine being pretty widespread. Is there a source of information that is trusted enough by the skeptics to open them up to taking a vaccine?

JOHN J LENNON You know, they came in after the court ordered that all New York incarcerated people in jails and prisons get the vaccine and they said yes or no. "You get gettin it or not. Let's go. Yes or no officers coming around, yes or no, that was inappropriate. I think we need to be a little nuanced about how we approach this. You know, there's a lot of influential prisoners. And if administrators don't lean into relationships with influential prisoners and they don't look to work with them, say, hey, we have this problem here, we are looking to get as many people vaccinated as we can, we don't want to tell you to press the population just to inform the population within candis conversations about some of the things I mentioned earlier, this is what's going to happen, he won't be able to use this or go on this visit or attend that. There needs to be more communication, Brooke, and you need to tap into your resources. We're not liabilities, some of us are assets. Many of us are assets.

BROOKE GLADSTONE John, thank you very much.

JOHN J LENNON Oh, thank you so much.

BROOKE GLADSTONE John J Lennon is a journalist whose work appears in The New York Times, Esquire, New York Magazine, The New York Review of Books, The Washington Post Magazine and more. He's also serving an aggregate sentence of 28 years to life at Sullivan Correctional Facility in New York.

Coming up way back when, actually not very long ago, when women reporters were muzzled on the battlefield. This is On the Media.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.