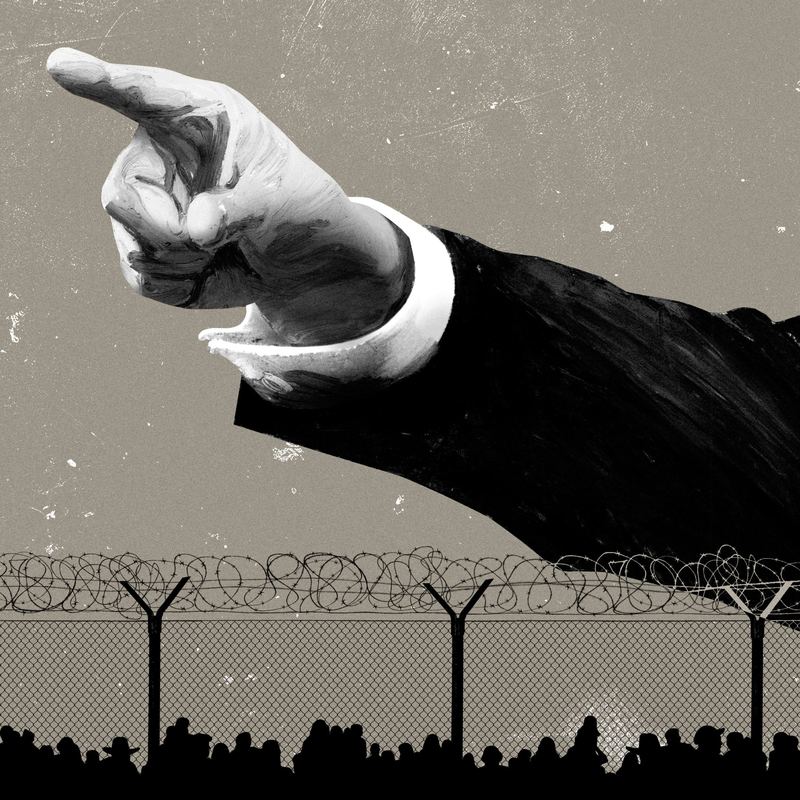

Inside Donald Trump’s Mass-Deportation Plans

David Remnick: Immigration has been the cornerstone of Donald Trump's political career for nearly a decade now. His first presidential campaign was largely about building the wall to keep people out. In 2024, the focus has been on sending back immigrants who are already here. He's promised the largest deportation in history. Millions of people potentially, and it starts on day one according to Trump. Stephen Miller said the administration would unleash the vast arsenal of federal powers to implement the most spectacular migration crackdown. A deportation policy on this scale would have enormous impact, not only on the lives of immigrants, but on their communities, on the US Economy, and much more. To understand what's really possible come January, I'm joined by staff writer Jonathan Blitzer, who's the author of Everyone who Is Gone Is Here, a definitive account published this year of the immigration crisis in America. Jonathan, before we get into the prospect of the Trump administration and a potential deportation, I want to ask you if you think, looking back on the now completed campaign, if the Democratic Party got immigration wrong, if the Biden administration ignored it for too long, as has been the critique all along from the Republicans.

Jonathan Blitzer: I definitely think the Democrats and Biden specifically miscalculated in thinking that if they put their heads down and didn't talk about this, the issue would somehow pass or it would dissolve in the general ether, and so they didn't really--

David Remnick: Why would they do that?

Jonathan Blitzer: It's tough news for Democrats all the time because the Republicans have a very simple, coherent message. It's plain and it's forceful and it's pithy, and that is, shut down the border, fewer people should enter the country. America first. It's the whole litany. Whereas Democrats have this issue of needing to communicate something more nuanced, balancing a humaneness with pragmatism at the border and beyond. That's always been a hard message for Democrats.

They've always toggled between trying to seem tough and trying to do things that at least are a little bit different than the Republicans, even though basically the tools in their arsenal aren't all that different. That said, the Biden administration, to my mind, made two major policy miscalculations. The first was clinging to a Trump-era policy for too long. It ostensibly was very tough. What it did was it allowed the government to summarily expel anyone who showed up at the southern border without giving them any real sense of due process or an opportunity to present claims for asylum.

It seems like it would be an effective way of clearing the border when you need to for the federal government. In fact, it actually had a series of counterproductive effects because the government was expelling people en masse without any orderly system around it. People were trying to cross multiple times. It didn't really stand up the asylum system or any of the border processing mechanisms that the Trump administration in its first term had sabotaged. It allowed the Biden administration to have a kind of illusion of control over the border when in fact, the circumstances were really spiraling out of their control.

That was the first thing. The second thing, and the one that I actually think ultimately was more definitive in terms of how it impacted the election, was Governor Abbott, Greg Abbott in Texas, busing tens of thousands of recently arrived migrants to blue cities and states across the country.

David Remnick: DeSantis as well.

Jonathan Blitzer: DeSantis did it as well. Each one wanted to outdo the other. DeSantis famously flew migrants to Martha's Vineyard to make the point that, how do you feel when it's in your backyard?

David Remnick: Can we agree then that it was diabolically effective as politics?

Jonathan Blitzer: Yes. I'll tell you, my conversations with top officials at the Department of Homeland Security all led to the same assessment, which was it was Greg Abbott more so than it was Ron DeSantis driving this reality, but that Abbott single-handedly changed the way immigration played as a political issue in America as a result of this busing. To my mind, a profound mistake made by the administration was not intervening and doing something more active of its own.

What you had was you had all of these buses full of migrants being sent all across the country with the deliberate aim of causing chaos in cities and states far from the border. There was no coordination. The governor of Texas, governor of Florida, were deliberately not giving heads up to local or state officials, and so it was really overwhelming cities across the country. If the Biden administration had bit the bullet and tried to take on some of that process itself--

David Remnick: Why didn't they?

Jonathan Blitzer: They were scared of the politics.

David Remnick: What are the politics?

Jonathan Blitzer: The politics were-- The attacks would write themselves. The attacks would be, look what the Biden administration is doing. It's offering newly arrived immigrants bus tickets to whatever city they want. That was the conversation inside the White House, that the bruising political fight around this is going to be just too painful for us. The operations themselves are complicated. No one's denying that it's complicated to draw up plans to relieve pressure at the border. The Biden administration essentially was defensive and allowed someone like Greg Abbott to really run the table on them.

David Remnick: Did it seem to you that this was partially responsible for the shift in votes in blue states like New York?

Jonathan Blitzer: I was struck by the fact that in some of the congressional districts in and around the suburbs of New York City, you had large numbers of people in response to polls saying that the border crisis was out of control. It was motivating their decision to vote the way they did. What was so striking about that for me was for six or seven months, if not longer, before the election itself, the number of people arriving at the border had dropped substantially. Yet, the perception in places like New York and beyond was that this was still an ongoing crisis because they were dealing with--

David Remnick: Are you saying it was merely a perception problem, not a reality problem?

Jonathan Blitzer: No, I think it was both. I think the reality was undeniable that for cities and suburbs that were dealing with the recent arrival of relatively large numbers of people for whom they were not prepared, I think that was a really acute strain on a number of local resources. I think it would have been manageable had the federal government been more proactive and had the messaging around it been a little bit more forthright. The Democrats tend to think, we lose on this issue because nuance loses against big, broad, ugly attack lines from Republicans.

The net effect of it all is the public is just bombarded with the Republican line time and again, and there's really no countervailing, narrative, rhetoric, explanation that unpacks a little bit what's happening.

David Remnick: Now, on January 20th, Donald Trump becomes president, and he has promises about day one and deportation. What is the rhetoric and what is going to be the reality?

Jonathan Blitzer: I have to say, candidly, I don't know what's coming. We know that there's going to be every manner of harshness, but the mechanics of mass deportation are complicated. It's unclear to me when people like Stephen Miller, Donald Trump's top immigration advisor and now someone who's going to play a very influential role in the new White House, say, as he has said recently, that the incoming administration is going to deport up to a million people a year. People should be skeptical of that number, the magnitude of that number. There's a huge amount of logistical coordination that would be required for that to work.

David Remnick: How many undocumented immigrants are there?

Jonathan Blitzer: There are upwards of 11 million undocumented people living in the United States, the majority of whom, it should be said, have lived here for more than a decade.

David Remnick: Right.

Jonathan Blitzer: To my mind, one of the scariest things about what's coming is the randomness of the roundups and arrests. One of the things that has guided enforcement policy, certainly among Democrats over the recent years, is in light of the fact that there are so many undocumented immigrants who've been living in the United States who can't regularize their status because Congress is deadlocked, the government has to prioritize who it goes after. For instance, people who have committed crimes. The whole specific list of things. What they're effectively saying is, ''Okay, if you haven't committed crimes, if the only issue you have is that you've overstayed a visa or that 15 years ago you crossed the border without authorization, we're going to deprioritize you for arrest to such a degree that you really do not have to look over your shoulder all the time.''

The Trump ethos and it's explicit, and was explicit in the first term, is if you're undocumented, you're fair game. You should be looking over your shoulder.

David Remnick: Here's Stephen Miller describing what he thinks is going to happen on the day of inauguration.

Stephen Miller: He will immediately sign executive orders sealing the border shut, beginning the largest deportation operation in American history, finding the criminal gangs, rapists, drug dealers, and monsters that have murdered our citizens and sending them home. No one will be allowed to enter the country illegally, and ICE will be empowered in partnership with FBI, DEA, ATF, The National Guard, to fully seal and secure the border with CBP and to find and identify the criminal threats that are inside this country and send them back home.

David Remnick: Jonathan, maybe you should break down what Stephen Miller is saying.

Jonathan Blitzer: In the first administration, Trump came into office with Miller and the whole lot of them, all planning to ramp up arrests and deportations from the interior of the country. In other words, people who have been living here for many years, who are undocumented, whose legal status has lapsed, and so on. They were going to be vulnerable. The government was going to go after them. What happened, in effect, was the situation at the border. Large numbers of people showing up because of conditions all across the region, in Central America and beyond, seeking asylum at the southern border.

The first Trump administration got, in many ways distracted from its agenda for interior enforcement and instead had to pour a lot of its resources and time into border enforcement. Some of the harshest, most upsetting things we saw in the first administration had to do with the government's treatment of asylum seekers at the southern border. For example, families getting separated at the border. That was all about trying to punish families who were showing up seeking asylum and basically mistreating them to such a degree, the hope was, that other people wouldn't even bother to make the trip.

What's happening now is going to be different. In large part, the Democrats now have also ceded a lot of ground on the border itself and on the asylum issue itself. As a result, you really already have a situation in which the border has been kind of locked down to a degree that it hasn't been before by Democrats. Joe Biden has done a lot of the original Trump bidding on cracking down on asylum seekers who cross between ports of entry, increasing penalties for people who try to cross illegally, and so on.

David Remnick: Are you saying the border is shut?

Jonathan Blitzer: The border is never shut. That's always been a political fiction. The numbers of people arriving at the southern border right now as a result of Biden policies and the policies of the government of Mexico are way down.

David Remnick: Now, Stephen Miller mentions criminal gangs, rapists, drug dealers, and monsters that have murdered our citizens, and we're going to send them home. What is the level of criminality among undocumented immigrants? Is it any different from the rest of the population?

Jonathan Blitzer: This is something that all through the first Trump administration, we were constantly having to insist on. Immigrant populations in general commit crimes at much lower rates than US Citizens. There is no evidence that there's mass criminality. There are always going to be one-off examples, and that's how these guys operate. That's how Miller operates both on the campaign and during these administrations. They find individual instances of ugly violence committed by undocumented immigrants, and they blow that up as though it's emblematic of some sort of trend, and it's not.

The knockdown effects of that rhetoric, and obviously the success of it politically, has allowed them to do increasingly harsh things to people who are entirely law-abiding, and the public, in general, throws up its hands and says, ''All right, well, this is the price we have to pay for getting the House in order.'' The thing that most concerns me in the immediate term, once Trump enters office, there are a lot of people who have arrived relatively recently, within the last couple of years who have availed themselves of actual legal pathways that the Biden administration created for them, but which were always provisional and temporary.

This is one of the problems of immigration policy. Presidents basically have to act now unilaterally, because Congress does not legislate on the issue, and so that allows someone like Trump to do very harsh things.

David Remnick: Presumably he'll have a cooperative Congress this time around.

Jonathan Blitzer: I think so, too. I think there's going to be also be less resistance among Democrats, who I think now are very convinced that this issue is a loser for them.

David Remnick: I'm speaking with Jonathan Blitzer, a staff writer at the New Yorker, and he's been covering immigration for the magazine since the first Trump administration. Jonathan, is it legal to involve the military and law enforcement agencies at the local level when you're deporting people? To add to that, we've heard a lot of comparison of what might come and what happened in the '50s with so-called Operation Wetback during the Eisenhower administration. How do they jive?

Jonathan Blitzer: That operation, Operation Wetback during the Eisenhower era is the only precedent, really, for just the sheer scale and volume of deportations that the Trump administration wants to carry out. At that moment in time, there were over a million people who were deported. In effect, what that meant was that a lot of US Citizens were deported because they were racially profiled and just rounded up en masse and sent to Mexico. It was an incredibly ugly, dark period, certainly a blot on the Eisenhower administration's record. I think now that's certainly the ambition is to recreate that kind of massive scale of deportations.

David Remnick: They've used figures like 20 million people.

Jonathan Blitzer: Yes. Those are fictions. That said, even if they fail in trying to carry out that incredibly ambitious agenda, they can cause immense suffering and damage in the meantime, and I think are ready to. For example, there was a study several years ago about the effects of a big raid in the early 2000s on a meat packing plant in Iowa. It was known as the Postville Raid. It was a giant raid. Huge numbers of people were arrested. Until the first Trump administration, that was the highest number of arrests ever made in a workplace enforcement operation.

There was a study that came out a few years later that looked at birth patterns among Latino children in the area, in the state, in the months and years after that raid. The study revealed that actually, the babies that were born in the ensuing years were smaller when they were born. The mothers had been so impacted by fear and anxiety about what they had witnessed that had impacted their health, and that that was measurable in the birth weight of the children that followed in the years after that raid. The consequences of this are bodily.

They're psychological, of course, but they are profound in terms of the social fabric, but they're born physically. You mention the fact that the incoming Trump administration is going to need the help of the military, the National Guard, and so on. I do think they're going to strain the outer limits of the law on that.

David Remnick: What is the law on that?

Jonathan Blitzer: I think the law, to be frank, we're entering unprecedented territory to some degree. I think what the president-elect is going to do when he's in office is he's going to declare a state of emergency, and that is going to, in the eyes of his lawyers and his legal team, give him carte blanche to involve--

David Remnick: The president of the United States is going to declare an emergency where immigration is concerned?

Jonathan Blitzer: I think that's how it'll look.

David Remnick: You've just reported on people who are in the country on what's called humanitarian parole. That means they're documented. What has Trump said about that program?

Jonathan Blitzer: Let me first say the Biden administration had a theory of the case at the southern border, and that was it needed to be increasingly harsh in between ports of entry, when people just showed up crossing the border, as they're legally allowed to do, seeking asylum. The Biden administration response has looked a lot like the Trump administration's response in its first term, which is to say asylum is mostly off the table for people.

At the same time, one of the major approaches they developed, the Biden team, was to use parole, which is a legal authority that presidents have used since the 50s, since, incidentally, the Eisenhower era, to basically say, ''Okay, in a situation of international emergency or acute humanitarian crisis, we are letting you enter the country. You can live here, work here legally for two years. We would have to renew that work permit every two years, but once you're here, we can help you regularize your status.'' The problem over the years has been there hasn't really been legislation to get people on a path to permanent status.

In the past, what you'd see decades back was, there'd be a humanitarian crisis in the world. The US Would parole maybe tens of thousands of people into the country, and then Congress would pass legislation that allowed them to adjust their status. What the Biden administration wasn't able to do because Congress wasn't acting at all, was it basically was paroling large numbers of people into the country, over a million people. That series of programs allowed the Biden administration to control the situation at the southern border to make sure that people's arrivals there were more orderly.

The consequence was something that all of us were witnessing over the last couple of years, and that is these people are going to have their status expire, and then what? Trump, from the very beginning on the campaign now, JD Vance has been equally forceful on this. They've all said they're not only going to revoke these parole programs, but they're going to go immediately after the people who availed themselves of these parole programs.

David Remnick: Thomas Homan, who's going to be the so-called border czar, said, and I'm quoting him here, ''It's not going to be a mass sweep of neighborhoods. It's not going to be building concentration camps.'' He also said they'd focus on targeted arrests. What does that represent? How much daylight is there between Homan and Stephen Miller in their stances? Homan, as you know, was an architect of family separation policy during Trump's first term, along with Miller.

Jonathan Blitzer: A lot of Obama-era officials were surprised by how harsh Homan sounded in Trump's first term because Homan had always been a tough law and order guy, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, ICE lifer. The view certainly in the second half of the Obama administration was that Homan is the kind of guy who may not agree with what our approach is, but is a team player. He can get the rank and file on board because people respect him based on his long career in the agency and so on.

A lot of Obama-era officials called me shocked when Homan started to say some of the really tough-sounding things he said at the start of the first Trump administration. I also think that that's basically what he always felt and he was finally given a chance to be unfettered. At the start of the first Trump administration, quite literally, Homan was at his retirement party in January 2017 when he got a call from John Kelly, then Trump's DHS secretary, later his chief of staff, saying, ''Listen, come back, don't retire.''

Homan excused himself from his retirement party at Immigration and Customs Enforcement. He's going into the private sector, lucrative job. He was basically lured back to head ICE because it was the career ambition that he had harbored all these years. When he says that there are going to be targeted operations and that the concentration immigration camps and all of the most nightmarish things that we've heard aren't going to come to pass, I don't think he's saying that because morally he's got a particular problem with those eventualities. I think it's more the fact that he is thinking about operations. He is thinking in terms of nuts and bolts of what arrests can look like.

David Remnick: What gives you the idea that he's lacking in any moral fiber?

Jonathan Blitzer: I've spoken to him a number of times and I've just never been convinced that there's a deeper sensibility or thoughtfulness about what it is he does. I talk to people who work in Immigration and Customs Enforcement and they run the gamut. Some people actually are more, more liberal than you would expect. Some are as harsh and tough-minded as you'd expect, but many of them share a certain recognition, at least, of the human factors at play, and they have different rationalizations for explaining away the fallout of making arrests.

Homan never to me showed a particularly deep reckoning with what was at stake, either operationally or in terms of actual human beings, and how all of these operations were affecting them.

David Remnick: We talk a lot about guardrails. In other words, the idea is that in the first term, there were institutionalists in key positions at the Pentagon, State Department, and that to the great aggravation of the president of the United States to President Trump, there were guardrails against him going too far. That's one theory of the case. Now the theory of the case is this time around, that there are no guardrails. What effect will that have on this issue?

Jonathan Blitzer: This is the most striking issue to my mind, where we've seen what it looks like as the guardrails start to fall away because we already have evidence of it from the first administration. I think actually DHS, Department of Homeland Security, was a microcosm of some of what we'll see in different federal departments in the second term, and that is during Trump's first four years, initially, you had people who would bristle at the idea of lawlessness at the department, who would push back against some of Miller's more outrageous ideas or Trump's particular whims.

Over time, essentially, what you started to see by the end of Trump's first term was people who at least had a fidelity to the department and its agencies fall away, either forced out, resigned out of frustration. At the time, there was an acting head of the department, the very end, named Chad Wolf, who basically did whatever Miller wanted, and what that looked like in the context of the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 was to have DHS agents patrolling domestic protest. That's genuinely scary stuff. That's beyond the pale of DHS activity. You were already starting to see that.

I think you're going to see everything be more unfettered. I think one of the consequences now of having something like the Department of Justice be run by people who have very little regard for the rule of law is you're going to see a more retributive campaign from the Trump administration that links up with the DHS agenda. One of the things that happened in the first Trump term was the government wasn't able to deport as many people as it wanted because there was resistance from local and state law enforcement in blue locales, in Democratic strongholds. Cities like New York, Chicago, Denver, and so on.

What the government wants to do when that happens is the government wants to threaten lawsuits and fight this battle with those jurisdictions to penalize them, to say, ''Okay, you're not going to play ball with immigration enforcement, fine. When you have a storm or a natural disaster, we're not going to send emergency aid to you.'' For the most part, those kinds of efforts got slowed down or tied up because of legal fights and so on. I think you're going to have much more concertedness between DHS and DOJ in the second Trump term in prosecuting its agenda and going after jurisdictions that don't play ball.

David Remnick: John, you've used the word unfettered. What does that mean in this context, and what will that look like?

Jonathan Blitzer: Let me give a very concrete example. ICE has a policy. It's not a law. It's essentially a regulation that discourages arrests at schools, hospitals, places of worship, courts, someone showing up for a court date, not appropriate to just sweep in and arrest them because you know they're there. That has basically been a rough guideline from one administration to the next and more or less held. There were breaches during the first Trump term. You're going to see stuff like that. You're going to see arrest operations in very scary and upsetting places where in the past you've not seen them before.

The aim here being to really create a sense of terror. That is going to be the modus operandi of the administration. There's a policy involving what's called collateral arrests. If there's a targeted operation and the government is going after a set list of people who they know who are undocumented. In the past, there have been basically regulations against arresting anyone you encounter along the way. That's going to be out the window. What that means is there's going to be a much freer reign of racial profiling from agents who don't feel like they have any sense of responsibility.

I think what you're going to see is workplace raids, which we have been spared because the Biden administration has sworn off of them, as the Obama administration did at a certain point. You're going to see all of these things come roaring back into the picture. I worry very much about DACA recipients, so people who came here as children, who got a special status during the Obama years, and who've moved on and built lives around this status. Trump tried to cancel that policy in his first term, and it got tied up in court. That is going to be under assault again.

I do think you're going to see an expansion of detention spaces in the United States. The private prison industry is going to do very well for its shareholders. I think the fact of all this is real. My hesitation in trying to project what it's going to look like is that we get very obsessed with what the numbers might be. I think those numbers are a little bit of a distraction. When Miller talks about deporting a million people, he's pulling that out of thin air. That's not something that he's going to be able to do.

They can cause immense destruction and devastation even trying to reach that goal, and so it's almost immaterial whether or not they reach a million. If they are able to do what they want to do, they're going to cause a lot of suffering and a lot of upheaval.

David Remnick: Jonathan Blitzer, thank you.

Jonathan Blitzer: Thanks for having me.

[music]

David Remnick: Jonathan Blitzer is a staff writer for the New Yorker, and you can find his article on humanitarian parole and much more reporting on immigration, all at newyorker.com

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.