Andy Borowitz on Our Age of Ignorance

[music]

David Remnick: Welcome to The New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. You probably know Andy Borowitz from his column in The New Yorker, The Borowitz Report. He's been writing satire and humor for decades. He started out in the world of sitcoms.

Andy Borowitz: As a sitcom writer, you need characters that you can throw stuff to every week, week in, week out, who are dependable and we'll get to laugh. Politicians become this little sitcom cast because we know how they're going to behave. We know that Rudy Giuliani is going to be a crazy drunk guy, and Marjorie Taylor Greene is going to talk about Jewish space lasers. They become very reliable sources of comedy.

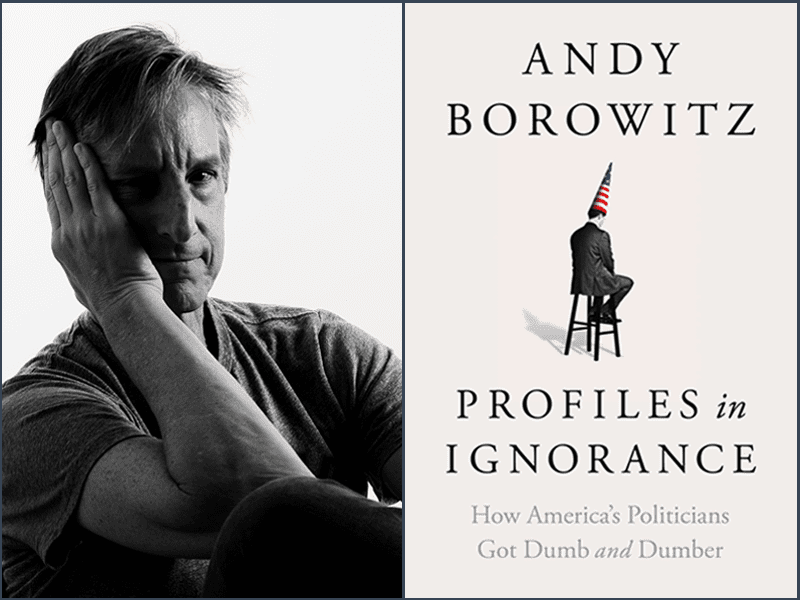

David: It's probably not surprising at all that Andy ended up writing about politics, but his new book, while funny, is not really satire. It's called Profiles in Ignorance. Andy believes we're now living at a time that some of our smartest, most educated politicians are actually just pretending to be dumb in order to get elected.

Andy, welcome. The book is hilarious. [chuckles] The subtitle of the book is How America's Politicians Got Dumb and Dumber, and it's mostly about obviously modern politicians. Were there no dummies early on?

Andy: No, there were. Apparently, this whole trend of dumbing down of politicians started during the 17th century.

David: [laughs]

Andy: What happened in then 17th century was that the Puritans were big readers. They mainly read one book, but they were big readers.

David: It was a good book.

Andy: It was an excellent book. Then a bunch of Dutch revivalists came in, and they started being much more theatrical and riving on the floor and hollering and yelling and all of this stuff. They quickly upstaged the Puritans. We've been reenacting that ever since, where we like politicians who can perform over politicians who know stuff.

David: What would you say is the zen of the politicians who know stuff? I assume it's the enlightenment period and the period of the declaration of independence and the constitution and things like that.

Andy: Yes, I think that's true. As a result, none of those guys are in my book because they're not funny. I focused really on the last 50 years, and the reason why I did that, it wasn't totally arbitrary, which was that the last 50 years was when TV got into the mix and really started with the Kennedy-Nixon debates.

Richard Nixon: Now, my point is this, Senator Kennedy has got to be consistent here. Either he's for the president and he's against the position that those who oppose the president in '55--

Andy: Two guys, by the way, who were both well informed. The problem was, Kennedy was much better on TV than Nixon. He had much better hair, and that really started the trend of politicians needing to have good hair whenever possible. You got people like Rod Blagojevich and John Edwards who had other problems.

David: Fantastic hair. Blagojevich had fantastic hair.

Andy: The best hair.

David: Ever.

Andy: What really happened with that debate was, it taught people a lesson and it was a dangerous lesson which is, it's important for politicians to be good on TV. Republicans in California reverse engineered this, and they said, "Rather than finding a politician like Nixon, who's well informed but loses the gubernatorial election because he's horrible on TV, let's find somebody who's great on TV and doesn't know anything. We can fill him with knowledge." That's how we got Governor Ronald Reagan.

Ronald Reagan: You've heard a great deal about my lack of experience. That's true. Lack of experience actually in holding public office, but I know that there comes some times when if you want a job done, maybe you get somebody in who hasn't found out all the things you can't do.

David: The start of the book, in some sense, is Ronald Reagan's ascent.

Andy: Yes. He is the towering icon of ignorance in this story. One thing I should say about the book is, nothing in this book is just my opinion. It's very documented. It's facts. It's not me just calling people names. I don't call people idiots. I will call them ignorami because that is actually a technical term. An ignoramus is somebody who doesn't know things.

David: Is it possible to argue that this enterprise, this discussion is, Conservatives equals ignorant and Liberal and to the left, it means enlightened somehow? One can only imagine that certain listeners listening to this, see this as an exercise in left-leaning, snobbery, or condescension.

Andy: That is a great question. I think that this issue of anti-intellectualism has really affected both parties. Bill Clinton is a great example, extremely well-educated guy, extremely full of knowledge. When he first ran in 1992, there was a lot of concern that he was too wonky and too nerdy because he had gone to Yale Law School and he'd been a Rhodes scholar and had gone to Oxford. The Democrats had a really bad record of nominating these guys who were considered eggheads. By the time Clinton came around, this was a concern and his way of addressing it, rather than owning how smart he was, is he started doing Elvis imitations. He went on the Arsenio Hall Show and put on Ray-Bans and played Heartbreak Hotel on the sax.

[music]

Andy: He was basically saying, "Hey, look, I'm not really that smart," and that was supposed to be a good thing.

David: He was talking about what kind of underwear he wore.

Andy: Exactly. On MTV, boxers or briefs. It wasn't like the Democrats looked at this anti-intellectual trend and said, "We'll have none of that." They eventually succumbed. Really, both Barack Obama and Bill Clinton, when they were looking for a political role model for their presentation, how to make their argument as a candidate, they looked to Ronald Reagan, one of the least informed presidents in American history. The least informed president became a role model for some of our most eggheady politicians.

David: Andy, you describe the last 50 years of American politics as the age of ignorance, and you divided it into three stages, ridicule, acceptance, and celebration.

Andy: To summarize, in ridicule, dumb politicians pretended to be smart. In the acceptance phase, George W. Bush, dumb politicians could be proud of being dumb. Then we have people like Josh Hawley, who's extremely well-educated and extremely smart, and they are part of what I would call the celebration phase of ignorance, which is, they are smart guys pretending to be dumb because it helps them electorally.

David: Tom Cotton is another, it seems.

Andy: Tom Cotton, Ted Cruz, there's a whole lot of them.

David: Along comes Donald Trump. Need I say more? Where does he fit in in all of this?

Andy: Well, what was interesting in researching the book was that, when Trump was elected, a lot of us supposedly knowledgeable people, were taken by surprise by this. It just seemed unfathomable, and it was just such a sock in the gut. The more I researched the past 50 years, the more likely plausible and maybe even inevitable his election was, because he actually had a great deal in common with his forebears. I think the thing that was different about him was, that he was really the icon of the celebration phase in that his ignorance and his ability to make up facts and to say really recklessly dumb things like we should all ingest bleach.

Donald Trump: Then I see the disinfectant where it knocks it out in one minute. Is there a way we can do something like that by injection inside?

Andy: That became a tribal banner that people wanted to wave. The notion that you had somebody who was saying things that were so ill-informed.

David: I somehow remember, [chuckles] and it seemed hilarious at the time, but it seems like almost nothing now, that the Vice President of the United States, Dan Quayle, visited a classroom. He, I think corrected a school kid's spelling of the word potato, but unfortunately, Quayle got it wrong.

Andy: This happened in 1992 towards the end of his vice presidency, and he was in a middle school classroom. Actually, the kid in question was named William Figueroa. The word he had to spell is potato and Dan Quayle said, "You've almost got it right there. You need to add a little something at the end."

Dan Quayle: Add one little bit on the end. [unintelligible 00:09:13] of potato. How was it?

William Figueroa: Thank you.

Andy: He hectored the kid into adding an E, thus disfiguring his correctly spelled word, and that really became the thing. That's the thing that he's best known for. Trump misspelled things on Twitter about once every five days when he was still allowed on Twitter.

News Reporter: Late last night, the president tweeted, "Despite the constant negative press covfefe."

Andy: It never became an issue at all.

David: There's been no shortage of comic writing about this, but at the same time, it doesn't embarrass Donald Trump to misspell a word every two seconds on Twitter. I distinctly remember him saying by way of compliment, "I love the uneducated. Where are my uneducated people?" This kind of thing. That's not to say that people who had not had the advantage of an advanced education or a fine one, should be looked down on. In fact, I think Trump scorns them as much as he scorns anybody, but is able to use it to his political advantage, is able to use the comedy about him to his political advantage too. What's to be done about this?

Andy: This might be my cockeyed optimism. I am an optimistic person actually, and I'm a little bit of an idealist. I do think that history doesn't move in a straight line. I think we've been in a very dumb period. The last 50 years have been trending dumb words clearly, but there's some hopeful signs.

I thought it was really interesting that the good people of Alaska decided that they'd had enough of Sarah Palin. I think that Sarah Palin's status as a national joke really finally caught up with her. I think it was a contributing factor. I think that there are other things about Sarah Palin that were a turn off to people. The fact that she quit halfway through her term as governor probably didn't help her.

David: I guess I feel after a while the times are such, and it's different from this high moment of Jon Stewart and some of the- it is not always funny anymore. These conspiracy theories and Jewish space lasers and the things that come out of Trump's mouth and Ted Cruz's mouth, which would've in a different context seem hilarious. Now, seemed just dangerous. You ever feel that way?

Andy: I think it's both really. I feel like this might be my manifestation of my cockeyed optimism, but I love this Will Rogers quote. I quoted in the book where Will Rogers said, "There's no trick to being a political humorist when you have the whole government working for you." I feel that we've lived through really terrible times in this country which in retrospect, they're in the mist of time now, in the mist of the past.

We're not living them viscerally anymore, but the McCarthy era was an era of conspiracy theories and a lot of people's lives were ruined. It wasn't just a question of somebody tweeting out a nasty mean tweet. It was entire careers were ruined. The early 1950s through the 1960s was a time where we were living on the precipice of nuclear annihilation. That wasn't really funny either. Yet people still, George Carlin was making jokes and--

David: Dr. Strangelove was made.

Andy: Every now and then people will say things like Tom Lehrer, the comedy songwriter, famously said that satire died when Henry Kissinger won the Nobel peace prize.

David: [laughs]

Andy: I get his point, but I just don't think it ever dies because I think we've always lived in absurd terrible times, some less terrible than others, but we find a way to laugh because it's really our survival, I think.

David: Andy Borowitz, thanks so much.

Andy: Thank you.

David: Andy Borowitz's new book is called Profiles in Ignorance.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.