How to Steal an Election

Kai: I'm Kai Wright and this is the United States of Anxiety, a show about the unfinished business of it our history and its grip on our future.

Speaker 1: We out here getting our young people, midwives folks in our CFOs, making sure they register to vote.

Speaker 2: To avoid spreading the Coronavirus at crowded polling places, States have adopted mailing voting.

Speaker 3: Absentee ballot envelopes sent to the wrong voters who then go on and sign them. There's this potential to disenfranchise a lot of voters.

Kai: Of course everyone's going to be watching for problems.

Speaker 4: In the past voting by mail has not given a partisan benefit to either party but what it does do is increase turnout.

President Trump: They had things levels of voting that if he ever agreed to it, you'd never have a Republican elected in this country against.

Speaker 5: Tell them to stop trying to disrupt the vote and to get their hands off of our democracy.

Kai: There is an ongoing COVID outbreak at the highest tier of American government and we still don't know its full scope or intensity. The world is left, speculating about the president's own health even as a growing list of Republican officials and advisers have also tested positive. In New Jersey, the State's urging everyone who attended the president's fundraiser on Thursday night to quarantine, that's roughly 300 people according to some reports.

This is to say nothing of the potential exposure for hundreds of others who have had to work or share space with all of these rich and powerful people. I say all of that to say, who knows where we are headed but one thing is absolutely clear. We are still holding an election and it is happening in the middle of a pandemic that plainly remains dangerous.

Rather than speculate about the COVID outbreak at the White House, this week we're going to learn about how people are trying to safely manage this election and about how the Republican Party is complicating those efforts. Today's show is a bit of a follow-up to my conversation with the historian Eric Foner last week. Eric reminded us that Americans do not have an affirmative right to vote.

Eric: There was nothing in the constitution that says who shall vote. The right to vote is still a very highly contested thing in this country even though you're a man and woman in the street would say, "Hey, that's what democracy is all about."

Kai: The constitution only says stuff about who you can't ban from voting based on race, or sex if you're over 18, et cetera but that leaves plenty of room to play for people who want to limit voting. Our senior editor, Christopher Werth has spent the past few months reporting on what that play looks like this year and he's going to tell us a story about it. Hey Christopher.

Christopher: Hey, Kai.

Kai: First of all, I feel like I've been through a lot in the last week and it seems like forever ago that we watched that dreadful first debate. One thing that stood out to me that night is, it feels like a lot more people made emotional contact with the fact that we are very likely heading for a post-election fight over the transition of power after the election. I wonder for you, what you thought of that moment when the president said basically that he already doesn't accept the idea that this is a fair election.

Christopher: I think this is consistent with what we've been hearing from the president for a while now. Republicans have pledged to spend $20 million in legal battles around this election. That's just a baseline number probably be much higher than that but Stanford University has put together a tracker of all the pandemic related legal cases around voting this year. It comes to over 300 lawsuits in almost all 50 States.

Republicans will say that those efforts are to prevent voter fraud as we've been hearing over and over and over again. There really is no substantial evidence that voter fraud is a big problem in the United States and President Trump himself, he said this in a political interview not too long ago that winning these types of lawsuits is really key to him winning a second term this year in this election.

Kai: Okay, you've been following this legal fight by zoning in on Wisconsin, which is obviously a key swing state, but what's special about it for voting?

Christopher: Donald Trump won Wisconsin by a tiny margin in 2016, it was just under 23,000 votes. I think what has happened there over the course of this election season since this pandemic started is really a cautionary tale about what could happen, not just in Wisconsin, but in other swing States come November.

Kai: Christopher is going to tell us two stories from Wisconsin. One is about the fight over voting itself, and the other is about the fight over how those votes then get counted. Christopher, where do you want to start?

Christopher: All right. We often tend to talk about voter suppression in very broad terms, but it affects real, very specific people. I want to introduce you to Melody McCurtis, she's a Black community organizer in Milwaukee, Wisconsin who got tangled up in this legal effort to make it hard to vote this year, but she is someone who quite literally, Kai, spends every day fighting these types of voter suppression tactics, trying to make sure everyone can cast a ballot.

Melody McCurtis: It has to change and I'm committed my life to that change because I have children growing up in this world and I don't want them-- I'm 27 now, I don't want them at 27, still fighting the same fight that I'm fighting, still fighting the same fight just a little bit different than my ancestors fought. We have to change the cycle. We have to change it.

Christopher: Melody was born and raised in Milwaukee. She's from a part of town called Metcalfe Park and if you want to see her in action, you might find her at the corner of 34th in Center Street. It's just outside downtown Milwaukee.

Melody: Now this is make it or break it, just trying to wheel people in.

Christopher: Melody is out on the street.

Melody: I'm on live.

Christopher: Picture her in a blue surgical mask. It's a hot sunny day. She's got her phone out and she's talking live on social media.

Melody: Hey, how're y'all doing? How're y'all doing? We out here, we out here--

Christopher: As we said, Melody is a community organizer and on this particular day, she's got all of these boxes of school supplies and groceries that she's giving out to the people in her neighborhood.

Melody: We have some of our folks out here doing the running man.

Christopher: They've got the street blocked off, they're volunteers at an intersection, dancing. They're letting people know where they are.

Melody: That's where we at, wherever you see somebody doing the running man at. You need to have a mask. Let me get your mask. Okay.

Christopher: A couple of things you should know about this part of Milwaukee, poverty rates are pretty high and so are the number of COVID-19 infections. Its interesting Milwaukee County is home to nearly 70% of all Black Wisconsinites and it accounts for over 40% of all COVID-related deaths in the state. To make sure that everyone can socially distance, Melody and the other organizers here, they've set-up these very distinct stations along the street.

Melody: When you pull up, you're going to hit the hand sanitizer, the touchless joy and you're going to come down here to Felicia, one of our residents superstars right here. She going to get you a book bag full of hygiene and household items, school curriculum, and toys for the kids. Then once you do that, you're going to come get the food right here. You're going to come get the food. I'm six feet apart, you're going to come get the food.

Christopher: There's something bigger going on here because in between all the boxes of groceries and everything else, Melody is working really hard to make the people in her community heard.

Melody: Then you're going to come over here, you're going to register to vote. You're going to do the census with these lovely people right here.

Christopher: When she's not at events like these, she goes door-to-door. She wears a mask. She's out there registering voters. She's talking about what issues are at stake or how people can request an absentee ballot or vote in-person. There have been a lot of new hurdles to the process of casting a vote in Wisconsin, the strict voter ID requirements. There are registration requirements. There are limits to early voting for example.

Melody: My main job is outmaneuvering our oppressors at this point. It's a lot of work. It's really a lot of work.

Christopher: If anyone knows how to navigate those hurdles, it's Melody, but in April of this year, she really found herself at a loss. This was when Wisconsin held its presidential primary.

Speaker 6: Well, many voters must now decide whether to heed warnings from public health officials.

Speaker 7: A lot of people are going to have to ignore that safer at home order so they can head to the polls.

Kai: I remember this story. This was the early days of the pandemic and as I recall, there were all these States that postponed their primaries, but Wisconsin plowed right at.

Christopher: The reason for that is, Wisconsin is in a political deadlock right now. There's a Democrat who sits in the governor's office, but Republicans control the state legislature and that is thanks to a highly partisan, deeply, deeply gerrymandered map that Republicans drew for themselves about a decade ago. While the governor, he wanted to put off the April 7th primary, the Republicans in the legislature, they've made that impossible.

Melody: I knew that they weren't going to postpone it.

Christopher: Melody has two kids, she lives with her mother who has a preexisting condition. More than two weeks before the primary, she requested an absentee ballot, which was well within the deadline.

Melody: Voting absentee really was my only option and that's why I made sure that I did all my steps to make sure that I could vote from home and I could vote from home safely.

Christopher: But because practically everyone else in Wisconsin did the same thing, there were major delays in actually getting those ballots. The state had never handled so many mailing voters in its history. Requests were more than five times higher than in 2016, and with just days to

go before the primary, Melody and thousands of other people still hadn't received theirs.

Melody: Then when I realized that it wasn't coming, I tried to call my clerk, no answer. It was insane.

Christopher: This situation posed a serious threat to voter turnout and it's what really turned to the state's primary into one of the first big legal battles of this election cycle. What's become a go-to strategy for making it harder to vote this year, as so many states are trying to make changes to their election rules around the pandemic. This is how it played out. Democrats asked for an extension. On April 2nd, so this was five days before the primary, a federal judge extended the deadline for absentee ballots by almost a week. It was six days.

Kai: Did that mean Melody had a chance to vote safely, then?

Christopher: If her absentee ballot arrived? Yes. The same, for thousands of other people in Wisconsin. Election officials sent out instructions advising voters of the new deadline, but republicans appealed to the US Supreme Court. On April 6, this was a day before the election, the five conservative justices on the court overturned that lower court's ruling. It meant Melody would have to go and vote in-person after all.

Melody: I was forced to go and put my mother's health at risk, my children's health at risk. It wasn't just my health at risk, it was my whole family.

Christopher: What the Supreme Court was using here is a precedent about election rules that comes from a case called Purcell, which we'll get into in a minute. Suffice it to say the court's argument was that allowing more time for those ballots to come in as the Democrats had wanted would create confusion amongst voters.

Kai: Well, it sounds like it was the Supreme Court that was doing all of the confusion creating. If voters were already hearing that they had more time to get their ballots in.

Christopher: Right, exactly. That has been one of the big criticisms of this decision. Because there were so few poll workers who were willing to take that risk, there were only five polling sites open in all of Milwaukee. It usually has around 180.

Kai: From 180, down to five sites.

Christopher: That's right, and lines, stretch for blocks that day.

Speaker 8: This is the line now. It extends for several blocks. Many people are wearing masks and keeping their distance from each other.

Melody: I had to go and wait in that line for three hours, amongst folks that everybody didn't have mask. There was no way to be six feet apart. Absolutely no way. I cast my ballot after 9:00 PM.

Christopher: What was it like for you emotionally standing in that line?

Melody: I was so angry. I was so angry, because I felt like in 2020, we were back to 55 years in the past. I felt like my ancestors and folks who came before me that fought for our rights to vote, we're turning in their grave that we were forced to go and risk our lives. What is telling me is that folks do not want me to vote.

Kai: Do we know what impact this had on the infection rates in Wisconsin, this primary? Do we know what happened?

Christopher: Yes. Statistical analysis out of the University of Wisconsin found that voting in-person that day led to approximately 700 additional COVID-19 infections in the five weeks after that election. I should add, 120,000 absentee ballots were never returned in that election, and another 23,000 were rejected.

We can't say that all of those were the result of the Supreme Court's decision here. Some of them were rejected because they were late, and some were rejected because they were filled out wrong. Again, this is a state that Trump won by just under 23,000 votes in 2016. These numbers, they really, really matter in Wisconsin.

Kai: These numbers are going to matter in a lot of these battleground states, I imagine. We're talking about a primary here, so presumably, a relatively low turnout compared to a presidential election and that means come November, we're looking at a lot more votes than that that are going to be lost in the shuffle.

Christopher: That's right. I think if there is an even bigger surge in COVID-19 cases later this fall, we could see more of that uncertainty that Wisconsin voters faced in that April presidential primary. As we know, the place where that uncertainty will play out this year is in the courts, and quite possibly the Supreme Court, which is now without Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Ginsburg wrote the dissent in that Wisconsin case. She said the court's decision, "boggles the mind." I think it's important to look at why the Supreme Court ruled the way it did in Wisconsin, why Melody was forced to wait in that long line?[

Luis Roberto: Let me turn this down. Hey, they're recording me, turn that off.

Christopher: I called up Luis Roberto Vera Jr. He's a lawyer who's been fighting voting rights battles for decades.

Luis: I'm sorry, we've got to turn off the MC in here. Can you hear me now?

Christopher: We spoke while he was at a medical clinic. He was getting routine treatment.

Luis: I've been on dialysis for 18 and a half years. I'm doing dialysis right now, while I'm talking to you. I get COVID I'm dead.

Christopher: Luis is very concerned about how the Supreme Court is handling election-related cases during the pandemic. He says the roots of what happened in Wisconsin have this really ugly history. It's one that goes back to another Supreme Court decision a decade and a half ago in Arizona.

Luis: Let me take you back a little bit. Remember that crazy Sheriff there Maricopa County?

Christopher: Joe Arpaio.

Luis: Yes, Joe. He was picking up every Mexican he could find claiming there were illegal and locking them up. Then he formed those 10 cities and everything else. They had the whole state of Arizona riled up that they were being invaded by Mexico and, "Let's save the state of Arizona." He had the support of the governor and all the politicians because Arizona wasn't controlled [unintelligible 00:16:09] Republicans. They decided that on their own without any evidence that the Mexicans were committing all this fraud because they were voting illegally, which turned out to be a total fabricated lie.

Christopher: This was back in 2004 and it was the start of what would become a wave of voter ID laws that have since gone into place around the country. Arizona was among the first. It passed a law that required proof of citizenship to register to vote and specific types of photo ID to cast a ballot.

Luis: If you lived in the middle of no freakin where in Arizona, or you're hours away from being able to get the ID they wanted just so you could vote in your own County, you weren't going to do it. You couldn't do it. It's too much of a burden, especially for the elderly, the poor. It was just another barrier to stop people from voting.

Christopher: Tens of thousands of Arizonians were at risk of not being able to cast the ballot. Luis's organization LULAC or the League of United Latin American Citizens sued, along with a number of voters in Arizona in a case that would eventually come to be known as Purcell v. Gonzalez. This was right before the 2006 midterm elections. To make a long story short, the voters in this case initially won. A lower court in San Francisco put the voter ID requirements on hold and then, as in Wisconsin, Republicans turned to the Supreme Court.

John: I know where I was when I got the order that the Supreme Court wanted briefing on the issue.

Christopher: This is John [unintelligible 00:17:48]. He's a lawyer who helped argue the Purcell case.

John: I thought to myself, this is not good.

Christopher: The Supreme Court overturned the lower court's ruling. It was the court's reasoning that John says has come to really haunt elections ever since because what the court said in Purcell was that you shouldn't change the rules when you're too close to an election, even if those rules could disenfranchise voters.

Kai: Purcell, this is the precedent that Republicans used in the Wisconsin decision that you talked about earlier.

Christopher: Yes. Changing the rules is exactly what election officials have needed to do this year to make sure people can vote in this pandemic.

John: Every time I see the word, Purcell, my heart sinks.

Christopher: This rule has since come to be known as the Purcell principle.

John: Just so you know, 14 years later, my heart sinks. I see that word in every election cycle.

Christopher: Why does your heart sink?

John: Because I think the doctrine's gone way too far.

Christopher: Purcell has been used in case after case this year. Not just Wisconsin, it's been used in Alabama, Georgia. In Texas in June, it was cited as a reason for not allowing all Texans the right to vote by mail as opposed to just those with a disability or people who are over the age of 65. Then Purcell was used again when the Supreme Court decided over a million former felons in Florida had to pay all of their court fees before they can register to vote.

Kai: This Florida case, a lot of us have been watching it. Quite frankly, it sounds just like the kind of poll taxes that kept black people from voting before the Civil Rights Movement. There were also these literacy tests and understanding tests, all the stuff that people think we made illegal in the '60s, and here we are.

Christopher: Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote the dissent in that Florida case. What she said is that Purcell is being misused right now as a reason not to make voting safer during a pandemic. She said it followed this trend in the Supreme Court of "condoning disfranchisement."

John: Just because something's happening close to the election doesn't mean you should automatically vote this principle. I think that a lot of courts have been too willing to accept that argument, to the point that it becomes a shorthand way for courts to make it harder for people to vote in elections.

Christopher: Would it be correct to say that in this election cycle that Purcell to a degree has been weaponized?

John: It's been weaponized since 2006. We've never seen it to this degree because this election cycle is very tricky. COVID has created a lot of complications with respect to voting because a lot more people are going to vote by mail than ever before. The rules are going to be looked at more closely than ever. They're simply more cases.

Kai: There is simply more uncertainty about how those cases get resolved. It will likely be left to the courts, particularly the supreme court to decide how much democracy is enough this year. Up next, what Wisconsin has already taught us about the coming fight over counting the votes. This is The United States of Anxiety. I'm Kai Wright. We'll be right back.

[silence]

Melody: I woke up this mornin' with my mind stayed on freedom. I woke up this mornin' with my mind stayed on freedom, with my mind stayed on freedom

Kai: This is The United States of Anxiety. I'm Kai Wright. This week, our senior editor Christopher Werth is telling us two stories from Wisconsin about trying to hold an election in a pandemic. Christopher, you already told us about the ongoing fight over the act of voting itself. I guess now we turn to the question of how all of those votes get counted. Correct?

Christopher: That's right. In August of this year, there was a congressional primary in Wisconsin. What I did is I followed this election in real-time over this summer by following some of the people including Melody, who we just heard from who were trying to make sure everyone could vote and that every vote will be counted this year. Again, a cautionary tale about what we could see in the November election.

Kai: We pick our story back up with voting rights organizer, Melody McCurtis, back in August.

Christopher: For Melody, preparing for that August congressional primary, meant more voter registration drives, more food drops to neighbors, more community meetings. She often posts videos of herself singing, either at home or at the start of a big group zoom meeting. It's a form of release that she does.

Melody: I woke up this mornin' with my mind stayed on freedom. I woke up this morning with my mind stayed on freedom, with my mind stayed on freedom.

Christopher: In getting ready for that August election, one of Melody's primary focuses is all of those little barriers to voting we were talking about earlier, proof of residency requirements, for example, voter ID requirements, what republicans call safeguards against voter fraud, that actually have the effect of making it harder for people to vote.

Melody: My worst fear is that all of these "safeguards" which I call it disenfranchisement tactics, continue. Folks in communities like mine, which is primarily black, they have been disenfranchised by those safeguards.

Christopher: When I talked with Melody, she was deploying a small army of volunteers, several dozen of them to make sure people can clear those safeguards, and that they have an absentee ballot ready to go.

Melody: That means Tony on 34th Street, going to chop it up with all of her neighbors, going to talk on the porch, porch by porch, taking them to that side, making sure all of them is signed up and ready to vote. That means we go to Patrice at the senior building, and she go door-to-door and ensure all of her neighbors have signed up and ensure for the seniors, that they're filling out the ballot correctly, and really telling our community that 2020 has not been good to us, but we matter and collectively our votes matter.

People say, "Oh, my vote don't count," but the community votes count. What would happen if collectively we all voted in our district? That's a whole different conversation.

Christopher: Wisconsin is often held up as a model for how to conduct elections. It is the most decentralized system in the country. In a state of just four and a half million eligible voters, there are more than 1,900 county and municipal clerks who are responsible for maintaining voter registration rolls, operating polling sites, and a whole lot of other administrative tasks.

It's also a system that's largely built around in-person voting and like so many states this year, Wisconsin is dealing with a deluge of absentee ballot requests. 75% of voters cast absentee ballots in that spring presidential primary. To get a better sense of how that decentralized system might hold up in this August congressional primary, and therefore how it might hold up in November, I asked a poll worker who will be helping to count those votes to start sending me dispatches from her phone back in July.

Andrea Kaminski: Hi, it's Andrea. It's about eleven o'clock Wednesday morning, I'm at the clerk's office actually upstairs from--

Christopher: Andrea Kaminski is a former director at the League of Women Voters in Wisconsin. She's been volunteering at her local election office in Madison. It's about an hour's drive from Milwaukee.

Andrea: I'm in a room with about a half dozen people, physically distanced, all wearing masks.

Christopher: A lot of poll workers and volunteers set out the April primary, including Andrea. Many of them are older, some have cautiously returned.

Andrea: The people who are doing this, many are at high risk for COVID. We've talked about it and we just feel like elections are so important. That makes it an essential activity. There are people who are trying to discredit the elections in general, and not the least of whom is the President.

Trump: If we went to mail-in balloting our election all over the world would look as a total joke.

Andrea: We feel really that it's important to make sure that the elections go smoothly because anything that goes wrong is going to be fodder for those who want to discredit elections.

Trump: There's tremendous controversy on mail-in voting. I can say this, the Republican Party cannot let it happen.

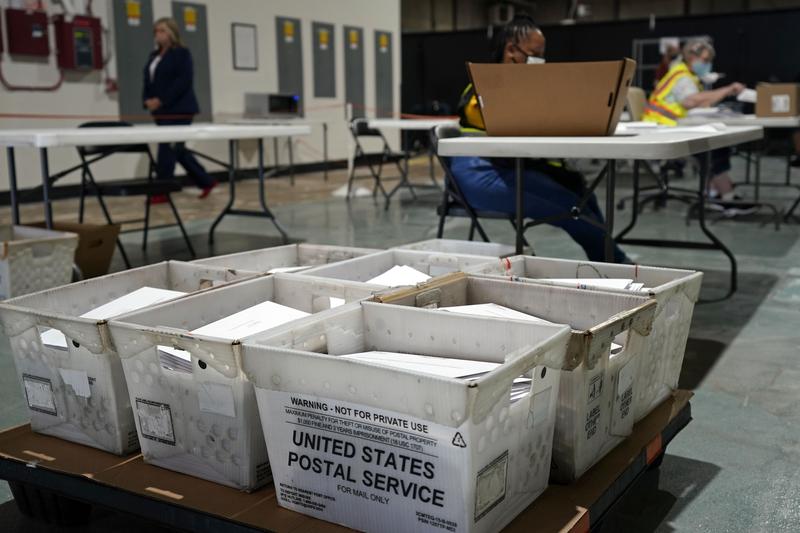

Christopher: Andrea's task is to get a handle on those mountains of absentee ballots. They've been pouring into the clerk's office.

Andrea: I just sorted the incoming mail. There were about 3,000 ballots in it.

Christopher: That's 3,000 ballots at one clerk's office in one day. Unlike many other states, Wisconsin doesn't allow any of them to be opened until Election Day. The scale is daunting.

Andrea: One frustration is that many of these ballots certainly won't be counted. Probably a good number.

Christopher: That's because the outside envelope on those ballots are required to have a number of things, including the voter signature and the signature of a witness, meaning another adult who watched you fill out your ballot. I'm told this rule has snagged a lot of voters this year, especially older ones who live alone and are socially distancing.

Andrea: Any one of those things missing and that ballot will be rejected.

Christopher: There's another snag and it comes from a law that now requires that witness to also write their address on the outside of the envelope, even if it's the same address as the voter's. In that April presidential primary we told you about earlier, nearly 14,000 ballots were thrown out for not having the witness signature and a witness address.

Andrea: That's a relatively new requirement that seems to trip a lot of people up.

Christopher: That witness can be your spouse, for example, or someone in your house.

Andrea: In most cases, it is someone else in your household. It turns out, a lot of people apparently don't think they have to put in the address because the voter's address is right up at the top of the certificate and they probably thought, "Well, my address is up top anyway so why do I have to write it all out?"

Christopher: This is something the Republican legislature added to the requirements a few years ago.

Andrea: Yes. In Wisconsin, the legislature, which wants to keep restricting voting has had the upper hand.

Christopher: The goal now in the clerk's office is for multiple election workers to look over each of those thousands of ballots, flagging envelopes for errors, and calling voters to let them know when they haven't done it right.

Andrea: It's tedious work, but if we can catch it early on our clerk's office will reach out to the voters and let them know there's a problem and we hope they can remedy it before the election.

Melody: All right. Basically, we're here today to welcome you all to Metcalfe park

Christopher: In Milwaukee, about 80 miles from Andrea's election office, Melody is watching what's happening with the US Postal Service.

Speaker 9: Tonight a backlog of undelivered mail is piling up in post offices around the country.

Speaker 10: Overseen by a key Trump ally--

Christopher: At this point, there are just days to go before the August congressional primary. Melody is determined to make sure no vote is lost. She's urging everyone in our community to skip the mail and take their absentee ballots directly to an early voting site.

Melody: We're requesting that folks just take it to one that is the closest to our community. It's like eight blocks outside of Metcalfe Park, but this is the closest location.

Christopher: All of this information, how to do the witness signature, the witness address where that drop off site is, and what kind of ID you need to vote, it's all on a pamphlet that Melody and her team took into each of those boxes of groceries and other household supplies they're handing out around the neighborhood,

Melody: That stuff doesn't come to their door. It's on us to ensure that that information gets our folks because we know that nobody else will. Can I do a walkthrough with you?

Christopher: Yes, that'd be great. Melody uses her phone to walk me through her office. It's piled high with supplies, ready to go out the next day.

Melody: I'm in the room right now where there's boxes and boxes of all of these bags that they made. We have things like tissue, soap, Kleenex, tampons, mask, toothpaste, toothbrushes, dishwashing liquid, hand soap, laundry detergent, all of these different things, and it's packed--

Christopher: Even with this big push for mailing voting, Melody says she still has residents who want to vote in-person to physically see their ballot go through the machine.

Melody: Monday we have folks come in and get voter safety kits. They have gloves, pans, masks, and hand sanitizers in those kits. I want people to be able to vote.

Andrea: Election Day, Tuesday, August 11th.

Christopher: The next time I hear from Andrea in Madison, the big day has finally arrived.

Andrea: The poll's been open for almost an hour.

Christopher: She's at her polling site, a church basement with plexiglass barriers to protect her and the other poll workers but it hardly feels like there's much to fear.

Andrea: We don't have a big in-person turnout. We've had all of two live in-person voters so far.

Christopher: This apparently is what mailing voting looks like. What they have, instead are all those absentee ballots that couldn't be opened earlier. The ones that were piling up at the clerk's office. These are the types of votes that will determine not just the outcome of this primary, but which way Wisconsin goes in November but there's a problem.

Andrea: What we're finding is that our scanner this morning is very persnickety, and it is not accepting any balance of the [unintelligible 00:32:53]--

Christopher: The scanner can't read the absentee votes.

Andrea: In some cases, you have to remake the ballot because it may be bent or creased, or one reason or another the scanner doesn't like it, so we do that.

Christopher: Remaking a ballot means that two poll workers have to sit down and fill out a new ballot exactly the way the voter had filled it out. Andrea says in past elections, there were usually just a couple of these but by noon, they'd remade 100 ballots. By the end of the day, Andrea says a third of all absentee votes weren't going through the scanner.

Andrea: When we called into our clerk's office to say that this was happening, they said, "Yes it's happening in places all over the city." For us, because we didn't have many walk-in voters it was more of an annoyance than anything. In the case of a busy election, it would be very hard and that's the situation that results in the election officials being there until 10:00, 11:00, 12:00 at night so tabulating ballots.

Kai: Well, in here again, Christopher, if we're talking about a presidential election, and it's going to be a third of the ballots, that is going to be huge. It's going to be way more than this already. It's going to take weeks for that to get counted.

Christopher: Right. Turnout will undoubtedly be a lot higher in November. Well over a million people in Wisconsin have already requested absentee ballots, which is more than the total number of people who voted in that August primary. If poll workers run into a problem, like the one Andrea experienced, that could really cause serious delays. I was talking with the election clerk in Madison, who she's expecting an unprecedented number of absentee ballots over the next month.

She described the process. Once they've opened these ballots on election day, they have to be flattened when they come out of the envelope. The scanners don't like the fold so they really have to be fed into the machines like in this very specific way. I think many of the voters in New York will know this because we feed our ballots into the scanner ourselves. That can be a challenge or if you go to your bank sometimes you can't get the cheque to go into the machine in a certain way. It's like that.

She said it's going to take a lot of work to just get those folded ballots. Once they go through the scanner, to lay flat inside of the ballot box, once they go through. She said it's like this dance that the poll workers are going to have to learn to do with those scanners this year. Wisconsin just doesn't have a lot of experience with mail-in voting at this scale and that is true of a lot of states.

Kai: Which, of course, this is the nightmare scenario that we've already been talking about a lot. The President has stated repeatedly and openly that he's going to exploit the situation that he does not want votes that come in or get figured out after election day counting.

Trump: The scam that the Democrats are pulling, it's a scam. The scam will be before the United States Supreme Court.

Kai: He spent months claiming that they're fraudulent. This means that we are definitely heading for the nightmare scenario that you laid out, it's going to happen. I guess the question is is there anything at this point that would stop this train?

Christopher: I did speak with someone who could provide at least some answer to that question. Her name is Amber McReynolds. She was an election official in Colorado. She now runs a nonprofit called the National Vote at Home Coalition. She said, yes, ballot scanners are one thing, but she says, the bigger barrier here is that Wisconsin and this is true of a lot of other states that are grappling with mail and voting this year, is that they are plagued by old inefficient laws and policies.

Amber McReynolds: For instance, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin all have a problem, and that they do not allow the election officials to process ballots in advance of Election Day. In Wisconsin's case, more time at this point would be extremely beneficial to them, given that they've got this challenge with this counting equipment that they have.

Christopher: Kai you remember how all of those absentee ballots were literally flooding in and how all the election workers could do was read what was on the outside of the envelopes. They couldn't do anything else until Election Day. MacReynolds say imagine if they could just go ahead and process the whole ballot.

Amber: Most states actually allow the pre-processing of absentee ballots before election day. Florida, Ohio, Utah, Colorado, all those states allow election officials to start processing absentee ballots right when they come in. Unfortunately, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, along with New York, Maryland, Iowa, Minnesota, those are all states that do not allow that advanced processing. That's going to ultimately delay their ability to get the ballots processed.

Kai: Well, and short of New York and Maryland, those are also all states that are likely to decide the outcome of this election. What would it take to change the policy in Wisconsin at least?

Christopher: McReynolds says that typically the governor of a state could do that. We mentioned this earlier, the Republican legislature in Wisconsin has really tied the governor's hands-on issues like this. She says all it would really take and this is true in many states is a very simple legislative change.

Amber: The legislature is really the only one at this point with the power to make that adjustment and that's just a matter of empowering the election officials with an ability to get the job done.

Christopher: In Wisconsin, has the legislature been approached about saying, "Hey, can you pass some emergency bill or just some measure that would allow early counting?"

Amber: We've had a few people reach out to a few different legislative leaders and our folks were told that there's no interest in passing any legislation that helps with mail ballot voting.

Christopher: Kai, I reached out to those legislative leaders in Wisconsin, including the majority leader in the State Senate. His name is Scott Fitzgerald. In fact, he just won a GOP primary in that August election that we talked about. He's running for a seat in the US House of Representatives. Neither he or the speaker of the state assembly in Wisconsin responded to our request for comment.

Just last week, both of them sent a cease and desist letter to the election clerk in Madison, because she's created this program that puts poll workers out in city parks around Madison to collect absentee ballots.

Andrea: It's Saturday, September 26th, and I'm at Democracy in the park.

Christopher: I got another message from Andrea. She was at one of these events last weekend.

Andrea: We're on a very active bicycling and hiking path.

Christopher: These are trained election officials who set up tables outside. You could drop off your ballot or they could witness you filling out your ballot and sign it as your witness, that whole process that we talked about earlier, you could register if you hadn't done that already.

Andrea: This was a way to bring democracy out to the people.

Christopher: Republicans claimed it was illegal. She and the other poll workers were warned that people from other parts of the state were coming to act as outside observers.

Andrea: This was a chilling email that came from the city clerk's office. What it said was possible was that there would be confrontations in the parks over this very positive program that we were all participating in. It just made me really sad and it made me a little nervous about how to handle it because I totally don't understand why people don't want other people to vote.

Kai: Andrea, says she didn't see any of these outside observers.

Andrea: Today we had one person who gave us less than nice feedback that I would not be able to repeat.

Kai: In fact, she said the vast majority of people were really supportive and everyone would cheer when someone would turn in a ballot.

[applause]

Andrea: They were thanking us for being there, and giving us the thumbs-up sign. I have never in my life been told by so many people that what I'm doing is legal. They wanted to make that point and we really appreciated it.

[music]

Kai: Christopher Werth will be following the voting story in Wisconsin and around the country for us throughout the elections so stay tuned but for now we need to talk about what's happening here in New York. We frankly had a number of problems this year, but most recently the board of elections sent mail-in ballots to roughly 100,000 people in Brooklyn with incorrect names on the return envelopes, which means if you send it back, your vote won't be counted because your signature won't match the name on the envelope.

They've sent out new ballots. Hopefully, that is all going to be resolved but WNYC Brigid Bergin has been covering this story and actually has been deep in the board of elections business for years. She joins me now to just give us the lowdown on how to get your votes counted this year. Brigid, thanks for making this time for us.

Brigid Bergin: Hey Kai, great to be here.

Kai: First of all, before we get into the important details about how to vote, can you just help me understand the context because New York State is extremely controlled by Democrats which is a party typically associated with making voting easier and more accessible and yet we constantly have these chronic problems with administering elections. Why is that?

Brigid: Kai, we have a very lengthy cumbersome election law that applies to all the localities and it dates back to the 19th century, it is archaic, it is in desperate need of modernization, and in the last legislative session over the past two years since Democrats took of the New York State Senate, they actually have taken some steps to modernize it, adding things like early voting, but there's a long way to go. Some of those restrictions are what makes it so hard for these local boards of elections to carry out their business efficiently.

Kai: Basically it boils down to like the parties control the elections. Is that fair to say?

Brigid: Absolutely. Just last week in the aftermath of the situation you described where the New York City board of elections had mailed out these erroneous ballots to Brooklyn voters, a lot of people who were clamoring for the opportunity to ask questions of the head of the New York City board of elections, the staff head of it, the executive director, a man named Michael Ryan, the only group that was able to get time with him besides a few reporters where the Brooklyn democratic executive committee.

The head of the Brooklyn Democratic Party and assembly member named Rodneyse Bichotte and some of her executive committee members had over an hour of executive director, Michael Ryan's time to ask questions about what had happened and how to fix it but members of the general public and members of the press Corps at large really didn't have that opportunity.

Kai: We are yet another issue where we are haunted by our history, so let's get to some of that, a couple of the big things that people need to know about voting and all of this cast. First off, those people who got the wrong mail-in ballots, they've been sent new ballots for them and everybody else, what do you need to know about sending your ballot back?

Brigid: They will be sent new ballots. Those ballots should start to go out this coming week and when you fill that ballot out, obviously check and make sure on that return envelope, that your name is on it. It's really pretty simple, when you fill out the ballot, you want to pick your candidates, fill in your all those, don't write anything extraneous on the ballot itself.

You're going to put it in that return envelope, seal it, make sure you flip it over and sign it, and date it. That's an important step and then you're going to put it in the envelope that actually goes in the mail. For this election, you actually have to put postage on this envelope that's a change from the June primary for New York voters.

Kai: Tell us about this postage because that's one of the issues, is that it's unclear how much postage to put on it?

Brigid: Oh Kai, it should be so easy, but the ballots are different sizes for the different boroughs and despite repeated questions to the board of elections and to the United States Postal Service about how much postage should voters apply to their ballots, no one has been able to get a clear answer.

At this point, the guidance that we have heard some good government groups and others offer is two forever stamps should be enough. The truth is the policy of the United States Postal Service is to deliver the ballot, even if there is insufficient or missing postage, and then try to collect any additional funds from the local board of elections but it shouldn't be so complicated.

Kai: The takeaway for me is that if there's a problem, if I can't figure it out, just put it in the mail, it will get delivered.

Brigid: Yes, or in another way, you could do it if you're willing to go out is you can actually drop that absentee ballot envelope off at any early voting election day poll site or board of elections office and there will be a secure dropbox where you can leave that. You could circumvent the whole postal service altogether and still deliver your absentee ballot without having to spend a whole lot of time at a poll site.

Kai: In general, I have decided I'm voting in-person, I'm prepared to risk it, are people talking about that? Where do people fall on this right now? Whether you should just go vote in-person at this point?

Brigid: I think there's a lot of people who are thinking through how to make their voting plan and considering that they have options here in New York, even if you apply for an absentee ballot, even if it arrived, you filled it out. If you change your mind up until Election Day, you still have the option of voting in-person that is legal here in New York State and we have early voting.

That is one of those recent innovations. It starts on October 24th, you are assigned to a specific poll site so it's important to know where you're supposed to vote, but that is another option. Again, you do not have to worry about all these issues that come up with the absentee ballots or the postal service, and of course, on Election Day, polls are open from 6:00 AM to 9:00 PM but to your question, Kai, I think that's one thing that voters are thinking seriously about.

We saw an avalanche of absentee ballots during the June primary. For a variety of reasons the results were delayed and at this point, I think people want to cast their ballot with a level of certainty. The most certain way to do that here in New York is to vote in-person.

Kai: If you're going to mail it in, the guidance is do it by October 27th. Right?

Brigid: Right. Technically and in part due to some of the issues that came up during the June primary, ballots will be accepted even if they are postmarked the day after election day, which would be November 4th, and received on that day. However they're technically supposed to be received on November 3rd and postmarked on November 3rd and the United States Postal Service sent out a notice to all voters saying, if you don't send it a week before the deadline, they can't guarantee it will arrive.

Kai: Okay, we will leave it with that. Send it by the 27th, Brigid Bergin covers politics and voting for WNYC and Gothamist. You can find her detailed breakdown of everything you need to know about voting in New York at gothamist.com. The United States of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios. Jared Paul mixed the podcast version, Kevin Bristow and Matthew Miranda were at the boards for the live show. Our team also includes Carolyn Adams, Emily Boutin, Jenny Casas, Marianne McCune, Christopher Werth, and Veralyn Williams.

Our theme music was written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band. Karen Frillmann is our executive producer and I am Kai Wright. You can keep in touch with me on Twitter at Kai_Wright. That's K-A-I_Wright, like the brothers and as always I hope you'll join us for the live version of the show next Sunday, 6:00 PM Eastern. You can stream it @wnyc.org or tell your smart speaker to play WNYC.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.