How Not to Leak

( NSA )

BOB GARFIELD: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. Thomas Jefferson once wrote, “The whole art of government consists in the art of being honest.” Yeah, maybe back when art was mostly directed at depicting actual things. Now art, or at least the art of government, is more like abstract expressionism. The pictures the politicians paint are intended to mean whatever you, the voter, wants them to mean. In 2017, honesty is apparently passé, except perhaps in congressional hearings and you are deposed FBI Director James Comey talking about the manner of your firing.

[CLIPS]:

JAMES COMEY: The administration then chose to defame me and, more importantly, the FBI, by saying that the organization was in disarray, that it was poorly led, that the workforce had lost confidence in its leader. Those were lies, plain and simple.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Or testifying about your awkward private sit-downs with Donald Trump.

JAMES COMEY: I was honestly concerned that he might lie about the nature of our meeting, and so I thought it really important to document. That combination of things I’d never experienced before but it led me to believe I got to write it down and I got to write it down in a very detailed way.

DEPUTY WHITE HOUSE PRESS SECRETARY SARAH SANDERS: I can definitely [LAUGHS] say the president’s not a liar.

BOB GARFIELD: Principal Deputy White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders.

DEPUTY PRESS SECRETARY SANDERS: …it’s frankly insulting that that question would be asked.

BOB GARFIELD: Perhaps more insulting, to the nation’s intelligence, is that the question still needs to be asked. But in a headline-grabbing bit of honesty, Comey readily admitted that in order to supply some representational art to balance the president’s more phantasmal depictions, he shared his meeting memos with a friend.

JAMES COMEY: The president tweeted on Friday after I got fired that I better hope there's not tapes. I woke up in the middle of the night on Monday night, ‘cause it didn’t dawn on me originally, that there might be corroboration for our conversation, there might be a tape. And my judgment was I needed to get that out into the public square. And so, I asked a friend of mine to share the content of the memo with a reporter, didn’t do it myself for a variety of reasons but I asked him to because I thought that might prompt the appointment of a special counsel. And so, I asked a close friend of mine to do it.

BOB GARFIELD: In an era when official assertions command less authority than furtive ones, Comey resorted to a leak. Unconscionable, said Marc Kasowitz, the president's personal lawyer.

MARC KASOWITZ: It is overwhelmingly clear that there have been and continue to be those in government who are actively attempting to undermine this administration with selective and illegal leaks of classified information and privileged communications. Mr. Comey has now admitted that he is one of these leakers.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: For months now, so much of what we know about this administration, from the democratically disturbing to the gleefully humiliating, has come courtesy of an army of leakers.

[CLIPS]:

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: The AP has reported that President Trump threatened to invade Mexico, in a conversation with the Mexican president.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: A draft executive order that leaked out, it suggested the US could reopen CIA –

MALE CORRESPONDENT: What?

MALE CORRESPONDENT: - “black site” prisons overseas and resume waterboarding.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Sessions, the attorney general, spoke twice with the Russian Ambassador during Trump’s presidential campaign.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: The Washington Post reporting that President Trump disclosed highly classified information to the Russians.

BOB GARFIELD: And after each leak, a familiar refrain from the administration and the GOP.

PRESIDENT TRUMP: We’re gonna find the leakers, they’re gonna pay a big price for leaking.

ATTORNEY GENERAL JEFF SESSIONS: This has got to end and it probably will take some convictions to put an end to it.

REP. JASON CHAFFETZ (R-UT): Probably ought to put some handcuffs on ‘em and put ‘em in jail.

[END CLIP]

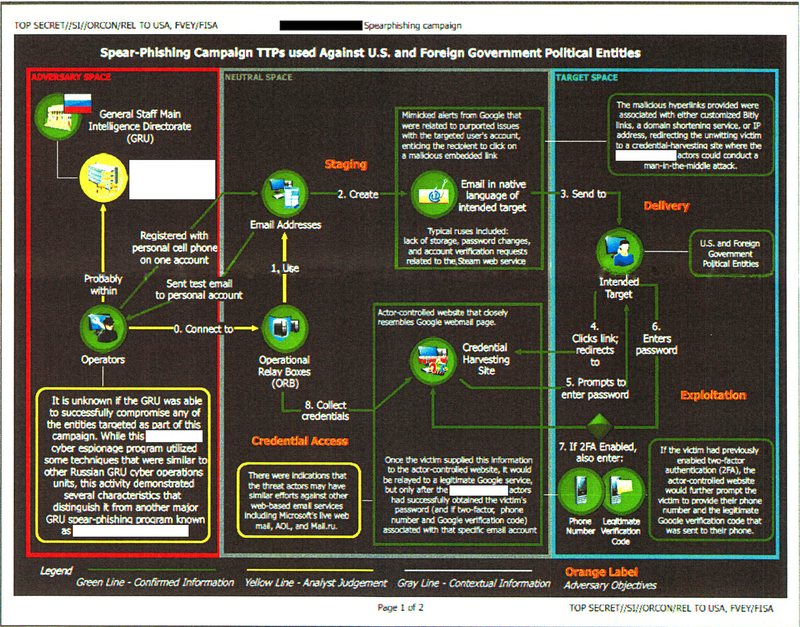

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This week, it seemed the hammer had finally fallen, on a 25-year-old NSA contract by the remarkable name of Reality Leigh Winner. Her arrest for leaking documents to The Intercept was announced just one hour after the investigative site published a top-secret NSA document, one that detailed alleged attempts by Russian spies to hack individuals connected to our voting infrastructure. According to the government, Reality Winner was found out thanks to giant breadcrumbs left by – The Intercept.

BARTON GELLMAN: The document had been creased. The government could see that and, therefore, could surmise it been mailed.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Barton Gellman was a longtime investigative reporter with the Washington Post and one of the journalists Edward Snowden leaked to. He’s now a Senior Fellow with the Century Foundation.

BARTON GELLMAN: More conclusively, modern printers often have what's known as fingerprinting, tiny, almost invisible dots that identify the printer, the computer from which it was printed and the date and time. Those things were easily readable by the forensics folks over at NSA. But it doesn't have to be nearly that high tech to give away the game. Many times, a sensitive document will go out with small watermarks or a trivial-looking piece of formatting, a word change, a numbering change, sometimes even a missing page, so that when the government wants to do a leak investigation it knows which copy the reporter has, if the reporter shares the whole document.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So in the course of authenticating the documents, The Intercept apparently also informed an intelligence source that the documents arrived in an envelope that was mailed from Augusta, Georgia. How was this wrong, Bart?

BARTON GELLMAN: So once you say you’ve got a printout, you’ve – [LAUGHS] you’ve told them quite a lot. The markings of the document showed that it was accessible by people in the NSA, other US intelligence agencies and intelligence partners in Canada, New Zealand, Australia and the UK.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

BARTON GELLMAN: So the universe of people who could have seen it or given it to The Intercept was quite large. It turns out that only six people in that whole universe printed it, and so, knowing that it was printed, knowing that it was mailed and then knowing where it was mailed from are almost checkmate for the source, at that point.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So when you're trying to validate the document, don't show the document, don't talk about how you got the documents or where it came from, don’t even characterize the document. Limit the validation to the contents of the document.

BARTON GELLMAN: That is generally what I'm saying. Now, it’s not possible for every reporter to be a communications security expert. What you need to have is a recognition, I have just crossed a line, I am arriving at a place where I need to pause and I need to consult an expert. And the puzzling thing here is that The Intercept has an unusually strong bench of expertise on this very subject. It has two world-class experts on staff. What’s baffling is that none of the four reporters or the editors involved in this story stopped and said, we better talk to those people about how do we protect this source.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And, let's face it, Reality Winner, if she is, in fact, the leaker, didn't exactly follow the best leaking practices. I mean, she didn't even follow The Intercept’s own advice. On their site, they specifically warn against contacting them online in any way, especially from work, which she did. Is there a way to leak safely from an agency like the NSA nowadays?

BARTON GELLMAN: There is no such thing as a perfectly safe decision to disclose some things that are powerful a well-resourced employer doesn't want you to disclose. A person in that position could have, for example, retyped the information or The Intercept could have done that, rather than send a printout -

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

BARTON GELLMAN: - could have mailed it from a place very far from home and would have scrupulously avoided any open contact with the news organization in advance or afterward. In an unrelated matter, she had connected herself to The Intercept. She asked for a transcript of a podcast some months ago.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The Intercept says that it didn't even know who the source was. If your source is truly anonymous, is it difficult to know how best to protect them?

BARTON GELLMAN: It’s definitely harder when you don't know who it is, how the person had access to the material. That's what should light up a bulb for you that says there are clues here that might not be meaningful to me but could be very meaningful to investigators. It would not have been obvious to me from a standing start that there would be so many people who could see the document but so few who printed it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

BARTON GELLMAN: But, just out of caution, I'm very parsimonious with facts when I give them to the government. What I want to do is I want to say, I have a document with this title and this date, which says the following things, and these are the things that I am thinking about printing, let's talk about these.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You’ve noted that it seemed weird that The Intercept would make what seemed to be kind of rookie mistakes? The Intercept, in its statement on the matter, suggests that we should be critical of the government's version of how Reality Winner was apprehended, that what we know so far might not be the whole story.

BARTON GELLMAN: Look, government affidavits for arrest warrants and charging documents are the government's version of events. You’re gonna want to see the evidence tested in court before you draw conclusions. And I sympathize that The Intercept can't talk about this right now. They may have something important to say about the way they handled the source or the way that the source behaved or the way the government behaved, and they're not able to say it for legal reasons now because anything they say could only do further harm to their source.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But you believe that mistakes were made by The Intercept. They did post the article on their website, so anyone could see it was a printout.

BARTON GELLMAN: I believe The Intercept made a series of very bad mistakes that doomed their source that they didn't have to make. The Intercept has real expertise at protecting communications security. I am certain that the reporters involved did not consult those experts because there’s no chance that those experts would have approved the steps they took. And I have no explanation for that. I don’t know how it happened.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: A lot of people worry that this episode marks the first step in the Trump administration's promised crackdown on leakers and that it will scare off the potential sources on which journalists and the public increasingly must depend for information. Do you have an opinion?

BARTON GELLMAN: I don't see any evidence in terms of action, as yet, that the Trump administration is crossing new lines. There have been leak investigations for as long as I’ve been a reporter, and that’s not especially surprising. Under George W. Bush and then under Obama, there was the quite unhealthy innovation, I think, of charging news sources with espionage, as if telling something to a reporter for purposes of a public report –

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm –

BARTON GELLMAN: - is the same thing as telling a hostile foreign power for purposes of harming the United States. If it is espionage to tell your own fellow citizens something because by doing so you’re also telling other countries, then we’ve lost the substantial meaning of espionage completely.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Bart, thank you very much.

BARTON GELLMAN: Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Barton Gellman is an investigative reporter for the Washington Post and a Senior Fellow with the Century Foundation. The Intercept declined our invitation for an interview.

[MUSIC/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Coming up, a debate over when it makes sense for journalists to make unsavory deals for access.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media.