How to End the Dominion of Men

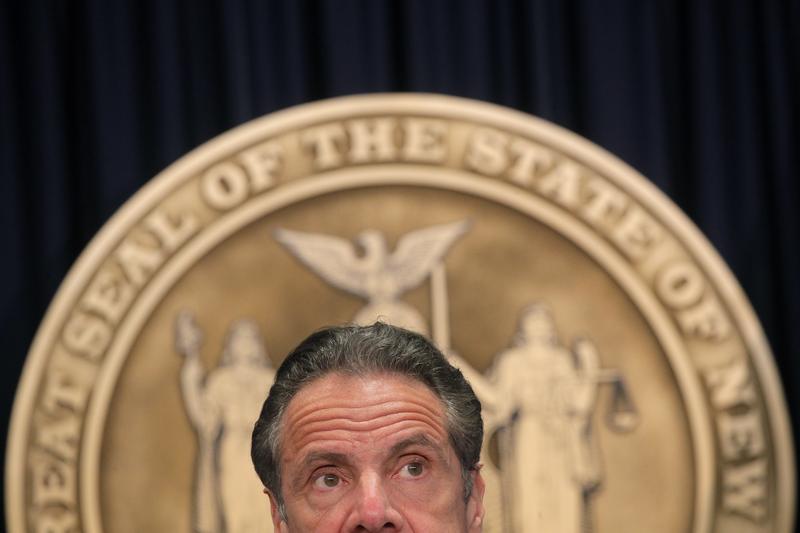

( Brendan McDermid/Pool Photo via AP )

Kai Wright: This is The United States of Anxiety, a show about the unfinished business of our history and its grip on our future.

Kat Banyard: This issue is still trivialized and dismissed. When we know actually that sexual harassment is a routine everyday experience for very many women and girls.

Gretchen Carlson: Even in the 21st century every woman still has a story.

Sen. Chris Coons: You bore this alone. You bore this alone for a very long time.

Marianne Cooper: Harassers are getting away with it because their power is shielding them from both discovery and punishment.

[chanting]

Ben Hurst: Boys will be boys. It's like a get-out-of-jail free card for any given situation.

Marisa Guthrie: It can't be the sisterhood against the old boys club, it has to be everybody speaking out about this.

Jackson Katz: What's going on? Why do so many men abuse physically, emotionally, in other ways the women and girls and the men and boys that they claim to love? What's going on with men?

[music]

Kai: Welcome to the show, I'm Kai Wright. It's been quite a remarkable few months for our New York's Governor, Andrew Cuomo. First, he absurdly won an Emmy for performing the role of a governor responding to the pandemic with authority or really for playing the TV dad foil to Donald Trump's crazy guy neighbor. We now know that all the while the governor was withholding unflattering information about his actual response to the pandemic. We also know that in the eyes of at least half a dozen women who have worked for Governor Cuomo, that TV dad was Trumpian in other ways too.

Male News Reporter 1: The governor is now facing multiple investigations.

Female Participant 5: Without explicitly saying it, he implied to me that I was old enough for him and he was lonely.

Andrew Cuomo: I now understand that I acted in a way that made people feel uncomfortable.

Female Participant 6: People put the onus on the woman to shut that conversation down.

Female News Reporter 1: A third accuser came forward this week telling the New York Times she met the governor at a wedding reception in 2019 where he asked to kiss her.

Female Participant 7: This is about dangerous and hostile workplace environments for young women and a culture that was perpetuated by very powerful aides to the governor.

Kai: Calls for Cuomo to resign have grown alongside these allegations of sexual harassment, and bullying, and even groping. As the saga has unfolded, it's made me think again about men, and the ways we learn to conflate our gender identity, our masculinity with domination over others. How do we stop that?

I don't know the answer. This week we're going to come at the question in a couple of different ways, an outward look at the law and how it changed, and a more inward look, at the sources of the harm we are so capable of inflicting upon one another. Settle in, first up is the story of an idea. There's this moment toward the end of the 1970s that marks a bright line in the history of the American workplace. There's really just a before and after.

It's the moment when a group of women in Upstate New York developed a new concept, and then worked their idea into the mainstream of American political culture. The story illustrates an awful lot about what it takes to bring about some kind of social change and how elusive real lasting change can be.

Linda Hirschman: Are you there?

Kai: Hey, Linda this is Kai.

Linda: Hi, Kai, nice to meet you.

Kai: Nice to meet you too. Thanks so much for coming in and hanging out with us.

Linda: Oh yes, I love to talk about this. This is the subject of my life's work.

Kai: Linda Hirschman studies social movements and particularly, the legal fight for women's equality. Her latest book is called Reckoning: The Epic Battle Against Sexual Abuse and Harassment. Right away, she gives me a big caveat here. You cannot boil a social movement down to a few people.

Linda: Victory has 1000 mothers.

Kai: Victory has 1000 mothers, and I totally hear that. Moreover, victory takes an awful long time because very clearly, we have not defeated sexual harassment yet. Still, it's useful to focus on a few particular mothers. Let's start with Carmita Wood, who was she, and what was her job?

Linda: Carmita Wood was a lab worker at the physics department at Cornell University in the late 1960s and early 1970s. She was promoted to be the Chief Administrative Assistant to the physics lab which was run at that point by a physics professor named Boyce McDaniel.

Kai: He was a big deal. He worked on the Manhattan Project and was a famous powerful professor on campus.

Linda: He had been pestering her for a while, but she was able to avoid him until she got this promotion. Here's what's interesting about her, she had four children. When she got promoted, she was able to get a nice house for them for the first time. The additional salary allowed this single mother to finally house her family, but it exposed her to this physics professor. He would follow her around, and he would make sexual comments to her. He would pin her against the wall or pin her against the desk and he would put his hands in his pockets and simulate masturbation when he had her within range.

Finally, at the Christmas party, he pulled her onto the dance floor, put his hands underneath her sweater, and at that point, she quit.

Kai: She had tried to manage it, but the guy just wore her down. She asked for a transfer and the university denied it, so she walked away, and she applied for unemployment insurance.

Linda: At the hearing, the hearing officer said that it was just a matter of personal taste that she didn't like it when her boss pushed her up against a desk and simulated masturbation at her. Since she had made the personal decision to quit, was voluntary and she wasn't going to get unemployment compensation.

Susan: They didn't even read the appeal. I remember thinking, "They couldn't have read this." They just said, "This is not a cause for collecting unemployment," which was the case across the country at that point.

Kai: Susan Meyer had just started working at Cornell. The university had just created a program for women's issues, and Susan, along with their partner, Karen Sauvigne, and an instructor named Lin Farley. They were interested in the workplace generally.

Susan: It's a lot of years ago.

Kai: She remembers when Carmita came to them to get help fighting the unemployment decision.

Susan: I believe we were actually in a room when Carmita was explaining to Lin's students sent to us what had happened. She was sick, the stress was getting to her, stomach problems, sleeplessness. If you hate going to work because you're afraid what you're going to find, you could imagine what that would be every morning.

Kai: Susan could certainly imagine. Carmita's story struck a nerve, every woman who heard it immediately recognized it.

Susan: The depth of the humiliation and the hurt. This is interesting. In my own personal story is my landlord. I lived in a small building. I thought we were friends. We used to talk about all sorts of things, and it turned out he wanted to get into my pants. That was what this was about. No, I was really hurt, crushed. I felt deceived. I'm sure everyone can relate to that kind of thing where you feel like you're being played, played with, that people think they can play with you because they have dominance.

Kai: Susan, and Lin, and Karen, and all of them knew right away, this was their new work. Carmita had cracked something open.

Susan: The ERA, abortion, rape issues. Women were organizing all over the place, but in some ways abortion and rape, are more visible issues. This was background noise, the background hum that you get used to, and you don't notice anymore. That was the status of sexual harassment. Between 1960 and 1980, women's participation in the workforce went from 38% to 51%, a huge jump. Men were threatened. There were women coming into the old boys' club, they needed to assert their dominance and make sure that women knew their place, and this is one of the ways to do that.

Kai: After meeting Carmita, Susan's group decided it had to confront the shame that was helping this stuff hide in plain sight, and this was 1975. They took a very 1975 approach.

Susan: Well, we did speak out. It was like consciousness raising but in a town hallway.

Kai: Meaning everybody just stands in public and testifies, says the thing out loud so others know it's not just a personal experience.

Carmita Wood: I used to feel so a part of that company, my company this, my company that. Well, it's the company and it's his company, and it's their company. It's not mine.

Kai: Events like this begin to spread all over the country.

Carmita: The guy came and went, [knocks] you didn't smile when I came out of the elevator.

Female Participant 8: Instead of trying to shrug off all the indignities and injustices, I think we really had to do it for survival.

Carmita: The office manager proposed bolting the typewriters to the tables to prevent this, and one of the lawyers said they should bolt the secretaries to the typewriters.

Kai: Ironically, the biggest challenge was that it was in fact such a common thing. It was too normal. They didn't even have words for talking about it as a problem, literally, the phrase sexual harassment, it did not exist.

Susan: The phenomena existed, right, but it didn't have a name. It was invisible. It's like the air we breathe. It's what's considered natural. It's your environment.

Kai: First, they had to come up with a name for this thing.

Susan: Okay. There are actually either five to eight women in a room. Karen and I sort of disagreed about it. I thought there was five. She thought there was eight, it doesn't matter, but the group of us, the three of us had expanded. Obviously, we had a larger group of women who we were talking to or who were involved and had been affected by this, and we knew that we couldn't go into a speak out without being very clear what we were doing, so we threw a lot of things around all of which I don't remember, but we came up with sexual harassment because it was the most inclusive.

Kai: They formally defined it, put it down on paper.

Susan: The definition, any repeated, unwanted, or unwelcome sexual comments, looks, suggestions, or physical contact that you find objectionable or offensive and causes you discomfort on your job. By labeling it, there's great power in naming and labeling a phenomena, without it, you don't see it. From the silence, you suddenly have a voice. You have something to hold on to and there was a very powerful moment. We knew that.

Linda: In social movements, this is true in all of the social movements that I have studied, which are many.

Kai: Linda Hirschman again.

Linda: There is a moment when someone names it. Until you can name it, you're politically powerless.

Kai: This was the spring of 1975. By late summer, words spread way past Cornell's campus. Lin Farley testified about it down at the Human Rights Commission in New York city, and a New York Times reporter heard that testimony, came up to Cornell, and then published a story with a full-page headline. It said, "Women begin to speak out against sexual harassment at work."

Linda: In 1975, it was, shall we say a matter of record.

Kai: Susan and Lin Farley and Karen Sauvigne, they became essentially political celebrities over the next few years. Through Carmita, they had created kind of a pre-social media, Me Too moment, and they knew they had really broken through when they landed on the Phil Donahue Show.

Linda: The Donahue Show, he was like the Oprah, the male Oprah of his time.

Kai: It's quite an exchange because first, Donahue was kind of setting Susan and Karen up.

Phil Donahue: What's your specialty keying in on the issue of sexual harassment at the office, which you say is pervasive, which you say many women take it as a matter of chorus, don't-

Kai: They're just delivering their big ideas.

Susan: We've been trained all our lives to be pleasing, to let men's egos off the hook gently.

Kai: Then, once he brings in the audience, it gets pretty jarring to the modern ear because you can hear a lot of people just are not buying it and there's a ton of blaming women.

Audience Member: Then also, there's a lot of women that enjoy it too.

[applause]

I think a lot of women are asking for it, by the way they dress or maybe flirting or something like-

Kai: Phil Donahue, he is clearly on Susan and Karen's side and they just keep making the case that this is an epidemic.

Susan: How many real lectures are there?

Karen: Unfortunately-

Phil: 1700, I have no idea.

Susan: Our studies have shown that women who have responded to questionnaires between what is it? 70% and 90% of all women who work experienced sexual harassment at some time during their work environments

Karen: It's not one man is running around doing all this. It's a lot of different men.

Kai: After this show, their celebrity just skyrocketed. Susan said they had people asking for their autographs, and they knew they had done something big. They had taken this thing that women experienced in isolation and shrouded in shame, and they'd given it a name, and turned it into a household conversation.

Linda: I can't describe the excitement of those years, this burgeoning of consciousness and the unifying of people around issues to make change.

Kai: Which was great as far as it went because one thing didn't change.

Susan: They could not help Carmita Wood, the unemployment people in New York were adamant. She disappears from view. It's very common that the early victims, they just break the ice. They don't get to drink the water.

Kai: Carmita died in 2015, and the professor who tormented her, he was celebrated right up into his death, but remember, victory has 1000 mothers. Carmita helped name the problem, but the next step was to change the rules. That's next. I'm Kai Wright, this is The United States of Anxiety. We'll be right back.

[music]

Kai: Welcome back. I'm Kai Wright, this is The United States of Anxiety. Before the break, historian, Linda Hirschman was telling us the origin story of the very idea of sexual harassment, not the behavior, that of course has always been with us, but those two words, sexual harassment. They were crafted by a group of women in Ithaca, New York, in the late 1970s to give a name to the thing that women were no longer going to tolerate on their jobs. It rocked the culture, but that culture change, as remarkable as it was, didn't change the law. Linda says that part, it was up to another woman.

Linda: In 1972, a woman named Paulette Barnes had been approached by her boss and said that she had to sleep with him, or she couldn't have her job. She refused, he fired her.

Kai: And she sued. She worked for the Environmental Protection Agency and she sued the government. Now, this was a huge moment because it was the first time somebody walked into a court and said, "You know what? This guy who's harassing me, he's actually violating my constitutionally protected civil rights."

Linda: She was an African-American woman, almost all of the critical plaintiffs in the first 10 or 15 years of the formulation of the sexual harassment legal claim were African-American women. In the best sense of intersectionality, I think that being both African-American and a woman did in fact play a role in the way that these very brave women saw that they had to fight the system.

Kai: Paulette's suit made its way up through the courts. In late 1975, just months after the women at Cornell had given this problem a name, the case landed in the Federal Appeals Court of Washington D.C., which was lucky because one of the judges on that panel was a Black man named Spottswood Robinson.

Faith Hochberg: You're bringing to be back like 40 years.

Kai: Robinson is dead, but Faith Hochberg was one of his clerks.

Faith: Judge Robinson was unusual because he had two female clerks. We were his only two clerks. He was an amazing man. If you don't know much about him, you ought to research him because he is one of the not sufficiently heralded figures of the civil rights movement.

Kai: Robinson had been a key part of the NAACP legal team that took apart this whole idea of separate but equal. He worked alongside his more famous companion, Thurgood Marshall, and that experience shaped him.

Faith: He was fanatically accurate, often to the point where his opinions didn't come out so fast, and when I spoke to him about it, he said it arose from his early legal work where when they were fighting these desegregation cases and other civil rights cases in the South, if they didn't have every single I dotted perfectly, they'd get thrown out of court, so he became the perfectionist.

Kai: He brought that to Paulette Barnes's suit, which forced the court to answer exactly the question Carmita had raised, was her experience just a personal matter or a sheared offense that created inequality for all women?

Faith: It was argued December 17th, 1975, so I would have been five or six months into my clerkship.

Kai: The Lower Court had rejected the suit outright. It never even made it to trial because they said Paulette Barnes didn't have a legitimate lawsuit, that the Civil Rights Act didn't cover this kind of thing.

Faith: When you read it now, you can't imagine why it wouldn't have been a cause of action. How could you throw out a case where a woman's position was eliminated because she wouldn't sleep with her boss?

Linda: Because didn't ask all of his women employees to sleep with him, he only asked, as far as we know, Paulette Barnes to sleep with him, so it was not like no girls allowed.

Kai: It wasn't about literal equal treatment of men and women because she wasn't being fired for being a woman.

Linda: It was not just the fact that she was a woman, but the fact that she was a woman who was attractive to her boss, but Robinson said, "We've already seen this in the racial cases and as long as sex or race plays any significant role in the behavior, it's enough. Otherwise, you'd almost never be able to win. People would say, "I'm not a sexist, I just don't want to employ women who have high voices."

Kai: Robinson believed the law had to recognize systems of subjugation, not just simple equality. He'd already fought to make that same shift in racial civil rights to focus courts, not just on equality between Black and white schools, but on the overall pattern of subjugation that segregation represented. Now, he applied that logic to gender equality, and Paulette Barnes won. The court agreed unanimously with Judge Robinson that she had a legitimate complaint. The government settled and Robinson logic stood as case law. For the first time, sexual harassment was grounds for complaint under the Civil Rights Act, but sexual harassment well, it of course did not stop.

Female News Reporter 2: This morning, with the announcement that longtime anchor Matt Lauer had been fired following a complaint about inappropriate sexual behavior at work.

Male News Reporter 2: Less than a day after harassment allegations surfaced against Charlie Rose, he has lost all of his job.

Female News Reporter 3: Five women have now accused that comedian and TV star Louis C.K. of sexual misconduct.

Kai: Why? There was a culture change, there was a legal change, and yet, why are we still so far down this dark alley? Susan Meyer has a thought. We're talking about events that took place in 1974 and '75. How do we deal with the thought that all of this amazing work went on, the law changed, the culture changed, it got named?

Susan: The thing is, there were some movies, there were some things. I don't think the culture ever really changed.

Kai: I asked Susan about one of my favorite movies.

[music]

Kai: This came out right at the same time Susan and her peers were foisting this idea into the political culture. I love the movie 9 To 5, but honestly, I never really thought about the cultural moment in which it landed, and what it had to say about that era.

Dolly Parton: If you ever say another word about me or make another indecent proposal, I'm going to get that gun of mine, and I'm going to change you from a rooster to a hen with one shot.

Kai: You remember 9 To 5 coming out?

Susan: I do.

Kai: What did you think a 9 To 5 when it came?

Susan: Okay, you want me to be honest to this?

Kai: I do.

Susan: Okay, I love these three women, great, right? It was funny. It should have ended on them unionizing. Seriously, the thing that we always had to say to women, you can't deal with this yourself, not only tell your family and friends, you have to talk to colleagues, because if you're being sexually harassed, you're damn sure that other women have experienced the same thing and you need to unify.

Kai: I think what Susan's actually talking about is a meaningful shift in power and that kind of thing takes a long time because nobody just gives up power.

Susan: You need consequences. If not, the men stay in the job, the women leave, and the culture goes on. I think we did the defining, we made it visible, we gave women a voice, we gave them some tools, we gave them some legislation and policy and legal backup, but you always need consequences, and until recently, the consequences were not widely known.

Kai: I hear that point consequences for our actions, but when I asked at the top of the show, how do we stop this? I also meant how do we as men stop doing it in the first place. There are all kinds of reasons people harass and bully others, men and women alike, and there are all kinds of reasons men harass and bully women specifically or anyone seen as feminine, really. To me, part of this is the conflation of masculinity and dominance. I certainly remember learning to link those two ideas as a young man myself. Coming up, I'll talk with author, Kiese Laymon about how to unlearn it. I'm Kai Wright. this is The United States of Anxiety. Stay with us.

[music]

Kai: Hey, gang, just a quick program note with your companion listening recommendation. As always, you can go to the notes for this episode on your podcast app and find links to related stuff in our archives. This week, one of the episodes you'll find there is called the 'Indoor Man and His Playmates'. It's a history of Playboy magazine, and Hugh Hefner's quite successful efforts to redefine the alpha male in his many entitlements. I hope you'll check it out. Also, just a heads up on the next segment in this current episode, the conversation you're about to hear does include a description of sexual abuse, so heads up if you're not in the space for that right now. Okay? Thanks.

[music]

Kai: Welcome back this is The United States of Anxiety. I'm Kai Wright, so in these news stories about famous men taking advantage of women. Stories like the allegations piling up against New York Governor, Andrew Cuomo, it's perhaps easier to see the role that power plays in it all because these men have clear and legible power in society and over the women they harass, but it's also easy to limit the conversation to these so identifiably powerful men when similar dynamics play out in relationships of all sorts every day between those of us who have learned to perform manhood or masculinity and the people we read as feminine.

There is it seems to me an intimate relationship between masculinity and domination, and listen, clearly, you do not have to be a man to dominate and abuse people, but to a disturbing degree, it sometimes feels like you can't be a man unless you do. I've thought about this dynamic a lot over my own life about my own struggle with it and against it, about how I learned it, how I can unlearn it, so I reached out to somebody whose work always prods me to think and to feel more deeply about masculinity.

Kiese Laymon's 2018 memoir Heavy was widely praised for its honesty and its poetry as he used his life story to publicly wrestle with demons that are so familiar to so many of us. He's just rereleased both his novel Long Division and his essay collection How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America. He joins us now, Kiese, thanks for coming on the show.

Kiese Laymon: Kai, thank you for having me.

Kai: We're going to talk about your writing and just see where this conversation takes us. To be honest, I'm not even sure where I'm going here.

Kiese: Okay.

Kai: Let's start with just what do you think of the premise I've set up in general, I don't want to assume you agree with it, this idea that we as people who grew up learning to be masculine just so often conflate that masculinity with domination over other people, do you think that's true?

Kiese: I certainly agree, it'd be hard to argue that that's not true. I'm interested in the roots of this conflation of masculinity and dominance. I'm also interested in what happens beyond the definitions. I'm one of these Black men who learned women's studies major and undergrad. I learned the language. The language helped in a lot of ways, but I wasn't sure that the language actually led to my wanting to actually be less dominant. Do you know what I mean? I definitely agree with your premise.

Kai: Right, it's one thing to think it. It's another thing to do things that give up the benefits you get from that dominance.

Kiese: Right.

Kai: Tangible and intangible. You begin your memoir, Heavy with a couple stories about the ways in which people in your childhood just took liberties with one another's bodies, and you tell a story about being 12 years old and an experience you had with some older boys and a teenage girl at your neighbor's house. I'd love you to tell listeners that story so we can talk about it from there in a concrete way.

Kiese: Sure.

Kai: You go over there to swim in the pool, just to set it up for a second here for you. You go over there to swim in the pool, and everybody wants to float in the deep end, and the older boys make you all first earn the right to swim, what happens? How does that play out?

Kiese: We were younger I was there with my friend Dougie, Layla Weathersby with an older girl, but she was also younger than the big boys. We just often had to do whatever they asked us to do before we could swim. This day what they said was Layla had to go in this room with the big boys. Dougie and I was supposed to like stay outside of the room and not enter. What happened was those three boys went into that room, and at the time, I didn't know necessarily what was happening, I had heard of this phrase running a train, but I didn't know what that actually meant, but I did know that whatever was happening to Layla, I was sure that I did not want that happening to me in that way, and I didn't help.

I was that third party bystander at 12 years old who was outside of this room with the girl I had a crush on, and she was in that room with these three bigger boys who, for all intents and purposes, made her go in that room with them if she wanted to do what we all wanted to do, and when she came up out of there, she was embarrassed and she asked me to walk with her out to the deep end so she wouldn't be so embarrassed in front of those boys and I didn't, I ran away. I was afraid.

Kai: Can you actually read that portion of the story? Because I think you write about it in a way that really, I think, is impactful, so she asks you to bring her some Kool-Aid and then walk her to the pool, as you said, to get into the deep end as promised. That's where this picks up.

Kiese: All right. I remember my back facing the opposite side of Daryl's room and wondering if there was a real word for stories filled with people who started off happy, then got sad, "Happysad," no space and no hyphen, was the word I used in my head. Telling happysad stories about what's just happened was really all the big boys at Beulah Beauford's house did well. Whether they were true or not didn't matter.

What mattered was if the stories were good stories. Good stories sounded honest. Good stories made you feel like you didn't see all of what you thought you saw. I knew the big boys would tell stories about what happened in Daryl's bedroom that were good for all three of them and sad for her in three vastly different ways.

I wanted to tell Layla some of the happysad stories of our bedrooms, but I wasn't sure whether to begin those happysad stories with "I", or "She", or "He", or "We", or "One time," or "Don't tell nobody," or "This might sound nasty to you," but. "I'm not starting to feel so good," I heard Layla say behind me, "What's wrong?" "I don't know" Without turning around, I whispered, "Me either, I mean, me too." Then, I took off out of Beulah Beauford's house, leaving Layla to walk by herself towards the deep end.

Kai: What is it you're confessing or maybe just sharing in this story, it's how you begin your memoir, what is it you were trying to share?

Kiese: I appreciate that question a lot, Kai. I think that what I'm trying to do is obliterate the convenient ways of talking about violence, sexual violence and assault that we have congratulated ourselves for using. I was outside of that room. I knew what was happening in that room to my friend, but I also, when she wanted to talk about it, I was afraid to talk about it because I would have to tell her about my experiences with sexual assault and sexual violence in my own house.

I was terrified, so what I'm trying to show early on in this book is like, "This isn't going to be a book where we can sit over here and say, 'We're the victims, we're the oppressors, we're the survivors, we're all of that at one time.' Now, let's try to go forward with that," so I wanted to start there because I think that conflation of all of these identities, I know actually starts long before we get any of this language around power and consent.

I just thought it would be unfair if I started that book any other place, in a place where I am at once someone who is hurting this young Black woman, and I also am as someone who has been hurt by older Black women, do you know? I think that's a murky place to start a book, but I just want it to start there.

Kai: You can't have this conversation in a generic way. Each of us learns our masculinity in our own individual context, as you're saying, and you and I both learned it as Black boys. In telling that story, as you're alluding to there, you write this line that says, "I was taught by big boys who were taught by big boys, that Black girls would be okay, no matter what we did to them." How important do you think that idea was at least for you to becoming a Black man back then?

Kiese: Crucial. I wouldn't learn until later that we call that patriarchy and Misogynoir, but that idea that you learn from-- In my community, I learned from big boys who learned from big boys who learned from men who learned from presidents that women generally, but specifically Black women would recover. I was also taught by those men who were taught by boys and taught by boys and taught by boys that we shouldn't care if Black women recover at all.

I just think that's something we should sit in and think about as people, and specifically Black boys, but I don't think sitting in it leads to any self-righteous stance because this destructive, violent earth is constantly shifting under our feet because we make it shift. I just don't want to do that thing where because we are talking, even on this conversation, we get labeled as the good guys or the good men, you know what I mean? We have lots, and lots, and lots of work to do, and I just don't think that work can have any integrity unless we go to the roots of where we actually started to encounter a lot of these ideas.

Kai: How long did you go on believing that idea or maybe you still believe it? Importantly, if you don't still believe it, how did you unlearn it?

Kiese: I definitely unlearned it, but I think unlearning it and actually operationalizing it in every part of your life is something different. I think it's important that you asked me that question. I was outside of that bedroom, Kai. For whatever reason, my grandma and my mama had created a boy who was never going to be one of those men who went into that bedroom.

I was never going to go in that bedroom and sexually assault that woman. Truthfully, I was never going to sexually assault any woman, but I think what society encourages me to do is pat myself on the back for that, and not acknowledge the fact that you cannot go in bedrooms and sexually assault women. You cannot initiate relationships with women and still abuse, gaslight, harm to the nth degree. I can say right here, right now, I know better. I know that Black women deserve far more than we and I have given.

I know the language to talk about that. I know the premises to explore, but I'd be a fool to sit here and be like, "I have exercised that." I want to, and I pray to, and I try to every day, but I think the second you think you're delivered from any violence, you are violent. I am a violent emotional person, and I had been emotionally violent to people, and I just don't think that there's any way for me to get through that if I act as if I've transcended it.

Kai: You also write about your own, as you said, the violence done to you and your own struggles with who you were as a man. My own experience learning Black masculinity was as a gay man, and I certainly didn't understand anything about my sexuality growing up, but I had the sense that I was different from other particularly Black boys in a way that would stop me from becoming a man.

I have to say, one of the things about your work reading your work for me is that I learned, and I think I may have learned it there. I learned that straight men had the same fear for different reasons and that was a shift in my thinking. I'm asking you, what role do you think that fear plays, that fear of not becoming a man or not being a man enough?

Kiese: Oh, my goodness. I don't know if I could answer that question honestly, really, but I will say at this point in my life, and this is how I know I have a lot more work to do, the worst thing is someone who loves me can say is Kiese, "You're such a man." because I'm talking all of this mess, but I want to distinguish myself from Trump, from R. Kelly, you know what I'm saying? From all of these folks who've done all of that. As much as I talk about not wanting to distinguish myself, I do want to distinguish myself.

I think we should, like those of us who have not done that particular harm, but I still think there's a trap right there. There's a trap once we think we are delivered from doing massive harm to Black women specifically. I don't know what's on the other side of when you realize that you were going to consciously and tenderly approach every relationship going forward this particular way. Yes, but what do we do with the harm that we've done yesterday? I think we try to repair that, but how? and I think that there's not a model for that, so we have to create it, and it's a messy creation, but I think that's what we're trying to do. I just hope that there's not a lot of collateral damage in that trying.

Kai: We've seen there are certainly a lot of collateral damage to ourselves and others, right?

Kiese: Definitely.

Kai: There's also a lot of fun and joy in Black masculinity, which you write about so well that I want to bring into this conversation too and again. I felt on the outside of that growing up. I took me way too late in my life to realize I related more to the joys of Black fem, even though it was very much a cisman, but it's funny. I don't even know how to ask this question, but it just seems like there's a push and pull between that fear of not becoming a man and not being a man, and all the great stuff about Black masculinity. I don't know. Can you help me out here? What am I talking about?

Kiese: I will say, I think some of the great stuff comes from when we shatter that mode of masculinity and it's so interesting because we'll shatter it, and then we'll try to put it back together. I played a lot of sports growing up and competitiveness was yes, a part and parcel of what we like to do, but we also love to touch each other. We love to hug. We love to hit each other on the butt. We love to like fart on one another's leg. We love to tow that line, supposedly, between homosocial and homoerotic, but, fam, it was all homoerotic. We'd love to touch one another.

I'm trying to say as a Black boy growing up and as a Black man, I want to be able to talk about how sublime it feels sometimes to be touched, period, but also to be touched by Black men. I think once we do that touch, we need to not do the work of, you know what I'm saying? Yes, touching you makes me feel so good, fam. Can we talk about that? That's what I think we need to do a little bit more of.

Kai: It's interesting to hear you say it that way too because you read a lot about your body and how you've thought about your body over your life, how you've wrestled with it, and that particularly, in relationship to performing masculinity, what can you say about your back and forth with your own body and how it's related to your sense of manhood and some of these questions around how we behave as men?

Kiese: That's a great question. I might go into TMI territory. Stop me, please, if I do.

Kai: Well, careful. We're on the radio.

Kiese: All right. Yes. I will say this, I think that all of the work some of us talk about doing, all of the stuff we write, I still think that I love that you've talked about this in terms of how do we personally deal with this? How do we interpersonally deal with this? How do we collectively? Personally, I need to think, for example, about why in all of my fantasies, I'm never me. I'm never this 46-year-old 300+ pound person, I'm always some version of between 22 and 34 year old who is super lean, you know what I mean?

I think that we have to mind even our imaginations, why in my imagination am I always the epitome of the manliest man I've ever been. I'm always ripped, my voice is always deep. The people in my imagination are always loving me, they're never questioning me. I just think that this work that you are asking us to do, yes, we have to do it on the local level, on the legal level, but the hardest work, fam, is that imaginative memory level.

How do we deal with that? I don't think you can unless you deploy and use language to talk about things you were taught not to talk about as a man. I don't think just talking about it is enough. I don't think we can even get to the other side because some of us are so afraid and haven't been taught how to use language to actually honestly explore our relationships to body and masculinity.

Kai: You've rereleased your collection of essays How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America. There's an essay in it that comes at this conversation straight on, it's called Echo. It's actually a chain letter between Black men in your life, other writers. Each writer reveals his own wrestling match with masculinity, and then tries to offer some wisdom to the previous writer. I guess your contribution in those chain letters, what is it you were trying to reveal?

Kiese: I think that I was trying to talk about this notion of knocking one's hustle. It's not even unspoken, but we talk about this unspoken code that I think, sometimes, people have and, in this situation, we're talking about men having. In my own situation, one of my mother's partners was brutal to her, brutalized her. I was always taught, and I can't remember the first time I was taught this, that you should never ever talk about what goes on in your house, particularly, if it was not flattering to your mother.

Often, that means that we were protecting, often the men who were brutalizing those women. For me, I wanted to say out loud to Darnell, to Marlin, to Kai, to Michael, you all, please hold me accountable if I do this because I do not want to do this, but I do not think I have the strength to not do it alone. What I was doing was trying to do two things.

One, say, "A Black man to a Black man, I need help." Two, say, "As a Black son growing up, I failed my mama," because of some bro code that I can't even remember where I was taught that code. I know that I was taught it, and I know she was taught it to to a different degree. I think that the failure to burst that code open led to a lot of pain and a lot of destruction in my relationship with my own body, in my relationship with my mother.

Kai: What were you doing with that whole idea of these exchange of letters between these men? It's a compelling way to craft an essay.

Kiese: I think at the time, all of us were playing with the epistolary form, wondering what happens if you actually not just wrote letters to people, but the people who you wrote letters to read the letters you wrote and wrote back. We're playing with this dialogic form. Also, we were just trying to do what we're talking about this conversation, which is to animate this desire and this need for Black men to talk and use language that we've never been encouraged to use when talking to one another.

What we didn't want to do is do it like the promise keeper thing where, we're Black men over here, Black femmes, Black women over there, we got to take care of our stuff. We were just-- because I think there's a total danger in that, but we did want to say, "In this space we have, we want to talk to each other in a new language that we haven't been encouraged to use."

Kai: The title essay in the collection, I will say, I was reading it this morning, and it feels it frustrates my whole thing with this conversation in that I'm looking for something more clean, that is real when people talk about how we do harm to each other. In the essay, again, it's How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America. It's about many things. It's about anti-Black violence. It's about guns generally, which it's on all of our minds as we have yet another mass shooting, we woke up to this morning with 10 people shot in Virginia Beach last night.

It's about your experience as a Black student at a white college and how they tried their best to make you crazy. I'm going to read what felt like the takeaway to me, this quick piece. You write, "This isn't an essay or a woe-is-we narrative about how hard it is to be a Black boy in America. This is a lame attempt at remembering the contours of slow death and life in America for one Black American teenager under Central Mississippi skies. I wish I could get my Yoda on right now and shift all this into a clean sociopolitical pull-quote that shows supreme knowledge and absolute emotional transformation, but I don't want to lie.

I want to say that remembering starts not with predictable punditry, or BS blogs, or slick art that really asks nothing of us, I want to say that it starts with all of us willing ourselves to remember, tell and accept those complicated muffled truths in our lives and deaths and the lives and deaths of folks around us over and over again." I guess my question for you about this is what about violence and harm doing, were you getting at with this sprawling essay that ends in that idea?

Kiese: Oh, well, again, I was trying to just work due to confluence of violences that we all embody when we walk through space. I think sometimes when we write these essays, we want to act as if, "Oh, we were only dealing with militarism, or we were only dealing with evictions, or we were only dealing with police brutality, or our schools treating us poorly," when in reality is all of those violences exist inside of us. They dictate how our bodies move, and none of the dictates are healthy.

What I'm trying to say is, "As much as I want to believe that you combat this circular violence and concentric violent circles with these self-righteous stances, like, 'This is who I am, and this is what I'm going to be.'" I think that those self-righteous stances are part and parcel of the masculinity we want to destroy. What I'm trying to say is, "It takes lots and lots and lots of messy work that will destabilize us. Actually, Kai, my question is, how much of that work should be public? I'm not sure because I do believe that the most important work has to be private and personal.

I also think because the stakes are so, so high, and the bar is so, so low for us, so much of this has to be public too, but I do wonder about this idea of outrage. When I hear that stuff about the governor is doing in New York, yes, I want to, and say, I'm outraged, I'm very outraged. Of course, it's expected, given who he is and how he performs in front of a camera. I think we have to go beyond performative outrage. What I want to do, and this is hard, is ask myself how much of what they're saying about that man is inside me.

I think that's the first move I need to make instead of being like, "Man, look at this loud talking asshole over here." Of course, how much of that dude is me? I think that's the harder work, and it's not performative. The answer doesn't come in one, two, three, four days, weeks, or months. I think that, right now, that's what I want to be. When I asked myself that question, the answer is nothing nice, period.

Kai: Period. Kiese Laymon's essay collection, How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, and his novel, Long Division have just been rereleased. His 2018 memoir is called Heavy. I urge you to check out all three wonderful books. Real quick, why release them now?

Kiese: I released now because I finally got them back. I signed a terrible deal with Independent Press. I got my money right. I bought the books back. I wanted to put them out. I always wanted to put them out in a different way. I finally got in a position to put them back out in a beautiful way. I just want to give my posterity and people who love me a chance to read the books as they were always intended.

Kai: Well, I hope everyone will do so. Thank you so much for this time.

Kiese: I'm so thankful for this, Kai. Thank you.

Kai: I'm Kai Wright. I will meet you back here next Sunday evening. Thanks for spending this time with us.

[music]

Kai: The United States of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios. Joe Plourde makes the podcast version. Kevin Bristow and Matthew Marando were at the boards for the live show. A special thanks this week goes to Jessica Miller, she produced the original version of our History of the Idea of Sexual Harassment, which first aired as part of another WNYC podcast I hosted. Our team also includes Carolyn Adams, Emily Botein, Jenny Casas, Karen Frillmann, and Christopher Werth.

Our theme music was written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band. Veralyn Williams is our executive producer, and I am Kai Wright. You can keep in touch with me on twitter at @Kai_Wright. As always, I hope you'll join us for the live show next Sunday at 6 PM, Eastern. You can stream it at wnyc.org, or tell your smart speaker play WNYC. Until then, thanks for listening. Take care of yourselves.

[music]

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.