How Boston’s Big Dig built our expectations of American infrastructure

( Michael Dwyer / AP Images )

[music]

Archival Clip 1: While people were still letting the wind blow them in various directions, men like Henry Ford, were putting their faith in the gasoline engine.

Archival Clip 2: Cars we drive have changed the life and face of our nation.

Archival Clip 3: We all know that motor vehicle registration is hitting new peaks, and we know too well that traffic jams are costing us time and money. Clearly, we must have more good roads.

Archival Clip 4: Highways were pushed across the desert. They are an indispensable part of our American way of life. They also make a gruesome contribution to our American way of death.

Archival Clip 5: Are we building cities for people or for automobiles? Will the 21st century bring a new era of human freedom and mobility or simply a world filled with autos and all that traffic?

[music]

Nancy Solomon: It's Notes from America, I'm Nancy Solomon in for Kai Wright. As we just heard, our country has seen an unprecedented amount of investment in infrastructure. It started spiking after World War II. It's not just roads, we built the Golden Gate Bridge, the Hoover Dam, and this one slays me, the Empire State Building was constructed in 13 months, and of course, there are the interstate highways.

Speaker 1: Congress responded with the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, providing the staggering sum of $51 billion to be spent by the states on highway construction by 1971. The most talked about phase of the Act is the Interstate Highway System, a 41,000-mile network of our most important roads.

Nancy Solomon: This was a big win for the automobile industry, which had been lobbying for a centralized highway system since the 1930s. In fact, General Motors designed what it would like and showed it off with an exhibit at the 1939 World's Fair. Roads ripped straight through cities, splitting neighborhoods apart.

Fred Salvucci: My grandmother was a 70-year-old widow. They came to her house in September and gave her $1, and a piece of paper saying, "The land is now ours, you have to go. We'll eventually give you an estimate of what we're willing to pay," and they just squeezed people.

Nancy Solomon: That's Fred Salvucci. He's an engineer who would go on to propose the most expensive highway project in American history, the Big Dig. Boston's Big Dig is a case study on everything that can go wrong when cities set out to build a big ambitious project. The excess time and money it took to complete the system of highway tunnels is a pointed example of why so many of us are cynical about infrastructure in America. My guest disrupts the commonly accepted narrative about the Big Dig with an audio series named for the controversial project. Ian Coss hosts a Big Dig podcast produced by GBH public media in Boston. He joins us now to share his reporting and help us think through what other cities can learn from the hard lessons of the Big Dig. Welcome Ian.

Ian Coss: So glad to be here.

Nancy Solomon: By the way, if you're listening tonight in Boston, or you have ties to that city, we especially want to hear from you. Tell us, how did the Big Dig impact your community. Thanks so much to GBH for airing the show because the Big Dig loomed large for so many of us with Boston connections, and that's where we're going to start. Ian, we are both from Massachusetts. I grew up in Lowell and Newton, what about you?

Ian Coss: I'm a little further west, Pioneer Valley, for those out there.

Nancy Solomon: The Big Dig was named for these massive tunnels that were created to take an old elevated highway that cut through central Boston, and was constantly choked with traffic. Describe the Big Dig and tell us what makes it different from other highways.

Ian Coss: Yes. The Big Dig is really interesting in that, it comes about at the moment in history when the tide is turning in terms of public opinion towards highways. We had this huge building spree of the interstates through the '50s and the '60s, and in the early '70s by that time, you have The Environmental Movement, you have a lot of citizens organizing to stop highways because of the destruction it caused in their neighborhoods. The Big Dig is born out of that moment. It's born out of the activism of that backlash.

From the beginning, the idea is that this is going to be a different kind of highway project, one that puts people in neighborhoods first. The idea was to take this elevated highway that ran straight through the heart of Boston, tear it down, and put it underground. You restore the surface of the city, and you retain that smooth transportation of the highway. That was the dream, is we want to have it all. We want to have our city back, and we want to have the highway. Of course, it turned out to be much, much more complicated than people thought at the beginning.

Nancy Solomon: You and I are from two different generations, I'm a little bit older, I grew up before the Big Dig, I spent hours of my youth in the backseat of the car stuck in traffic.

Ian Coss: What are your memories of the elevated, the old central artery?

Nancy Solomon: Stuck in traffic?

Ian Coss: Stuck in traffic.

Nancy Solomon: It didn't matter if we were going to the north shore to see our cousins or we were going to the airport to pick someone up. You just got stuck there. Getting into the Callahan Tunnel, oh, my God, you couldn't get into that tunnel without people yelling out their windows at each other. It was just many lanes getting into a one or two.

Ian Coss: I think what you have to understand about that highway is because a lot of cities have big elevated highways through the middle of them, and most of them did not get torn down. Part of what you have to understand about the Boston case is that this was an especially bad highway, not just socially in terms of the fabric of the city, but functionally. It was one of the earliest elevated highways built anywhere in the country. It had these narrow turns, it didn't have any breakdown lanes. The lanes were narrow too.

The worst part was that it had on and off ramps just constantly. All the businesses, all the city hall, everybody in Downtown wanted ramps when they built this thing. If you look over aerial shots of it, it looks like this weird millipede salamander through the heart of the city. It's just sprouting off ramps constantly at every turn, which really made it impossible to drive on.

Nancy Solomon: Yes. I mentioned that you were of a younger generation because when you're growing up, this is when the Big Dig is actually happening. Tell us a little bit about that because it really is astounding how long it took.

Ian Coss: Yes. I think of myself as the Big Dig generation, me and my peers of Massachusetts youth because the construction, I should say, started in the early 1990s. I was, I don't know, just barely walking maybe, and it goes on for 16 years, so I'm out of high school by the time it's done. Really was this project that just went on and on and on. You mentioned at the top of the show like, if folks in the Boston area have memories. It's not if. If you spent time in Massachusetts or Boston sometime in between the '80s, '90s, or 2000s, you encountered this, you heard about it, you talked about it because it was just inescapable.

Nancy Solomon: Do you have a Big Dig tattoo?

Ian Coss: Not yet.

Nancy Solomon: That would be the hallmark of the generation during the Big Dig. When I think about it, I always think of my father because he lived his whole life in Boston. He really truly loved the city. He thought it was the most beautiful place on earth. He had a cab driver's knowledge of all city streets in Boston, not that he was a cab driver. When the project was approved, he was super upset about it because he was 70 years old, and he knew that the center of the city was going to be torn up for the rest of his life, which is basically what happened.

You must have come across those kinds of stories. What is the emotional fabric that makes up the Boston experience of the Big Dig?

Ian Coss: I think this is, in some ways, what I set out to try and catalog in this series was not just the development and the story of this project, but the emotional arc of it, because it has a really profound journey. It begins-- The earliest conception and genesis of this idea like I said, is in the early '70s, into the '80s. At that time, it's this moonshot idea, this visionary idea. Cities are not doing this. This is not just par for the course.

People were really excited about it and you had broad political support. What happens during the construction is the narrative of the project, the perception of it. changes so profoundly from something that people were really proud of and inspired by, to something that was an object of ridicule and just constant outrage and scandal. Then if we complete the long winding journey of this thing, if you take a walk through Downtown Boston today, and you ask strangers on the street, like, "Oh, what do you think of this linear park, this Greenway that runs where the highway used to be?" People feel pretty good about it.

That is the emotional arc of The Big Dig, right? From vision to derision to a weird mixed redemption. I think of it as a hero's journey that this project went on. Like I said, that's what we tried to capture.

Nancy Solomon: We're going to spend a good part of this hour talking about the cautionary tale and the lessons and expand it out to the rest of the country. What is the cautionary tale? What are some of the lessons?

Ian Coss: Yes. There are so many. I think of the lessons of The Big Dig in two categories, and we could spend all night on either, or the subcategories of the categories. Here's what I would say, there is the technical stuff, wonky policy stuff that could have been done differently, and this is about how it was funded, how it was permitted, how it was contracted, how it was managed. Every step of the way, things, pretty much if something could go wrong if a stumbling block could be stumbled on, it went wrong, and it was stumbled on in the history of this project, that's one side.

The other side of The Big Dig story that I think is really important to study and learn from is the narrative piece, the story of the story, if that makes sense because that cynicism that grew up around this project at some point made it almost impossible for the project to function. I think there's a lot to learn there as a public in terms of the way we tell the story of infrastructure projects.

Nancy Solomon: We're talking to Ian Coss, host of the podcast, The Big Dig. It's a story of infrastructure mired in scandal that is all too familiar in America. I'm Nancy Solomon in for Kai Wright. Just ahead, we hear from you, what's your big dig? We've got Boston callers waiting on the lines, and we're going to hear from them. What's the public project that seems to go on forever in your town? Tell us how that's affecting your community by calling or texting 844-745, talk.

[music]

It's Notes from America, I'm Nancy Solomon in for Kai Wright.

Richard Nixon: The great question to the '70s is, shall we surrender to our surroundings or shall we make our peace with nature and begin to make reparations for the damage we have done to our air, to our land, and to our water?

Nancy Solomon: That's Republican President, Richard Nixon, giving his 1970 State of the Union address.

Richard Nixon: Restoring nature to its natural state is a cause beyond party and beyond factions. It has become a common cause of all the people of this country, it is a cause of particular concern to young Americans, because they more than we will reap the grim consequences of our failure to act on programs which are needed now if we are to prevent disaster later. Clean air, clean water, open spaces, these should once again be the birthright of every American. If we act now they can be.

Nancy Solomon: Nixon did act. That same year, he signed the National Environmental Policy Act. It required that all federally funded projects create environmental impact statements. Those would go a long way to protecting communities from unwanted projects but it also doomed big infrastructure projects. We're talking about one of the biggest infrastructure projects in American history with Ian Coss, he's the host of a new podcast from GBH public media in Boston called The Big Dig.

Bostonians, we're still taking your stories about what life was like during the decades of construction. What do you think of it now? No matter where you are, or where you grew up, we want to hear from you. What's your infrastructure project in your community you want to talk about? Call us or text us. I was so surprised, Ian, to learn that Richard Nixon was the president that brought us the environmental impact studies.

Ian Coss: Yes, the National Environmental Policy Act.

Nancy Solomon: I thought the part of your podcast where you talk about the unintended consequences of those statements in the ways that they can block, not just bad projects, but good projects. Tell us about that by learning about these statements and the two sides of the coin.

Ian Coss: When the environmental impact statement it first begins, in the 1970s, these things are a few pages long. It's something that the state has to prepare as part of a big project. By the time you get to The Big Dig, the Environmental Impact Statement is in the '80s, was thousands of pages long. It had started as this little bureaucratic process, became a huge, huge part of planning any big project. The key to understanding the environmental impact statement because I realized that sounds like a lot of word salad and jargon, the key, key thing here is that if somebody, anybody in the community, in the public, feels that a project has not adequately done its environmental impact statement, they can bring a lawsuit and they can sue to stop that project.

This is what makes the impact statement such a profound change in the way we build infrastructure because it creates incredible leverage for any kind of organized group to stop a project. I think The Big Dig is a fascinating case study in this story because to me, it captures that era of change. It begins in the 1970s, The Big Dig itself is part of that upswell of citizen activism. That is the ethos of this project, is to be a project that is good for the community. Fast forward, it's winding its way through its own environmental impact statement. It suddenly finds itself on the receiving end of that same upswell of activism and opposition.

I think there's an interesting irony there in the way that this project encountered its own environmental impact statement. It's complicated because I don't want to sit here and say that the environmental impact statement is a bad thing, and all it does is slow us down. The environmental impact process is an incredibly important forum in which voices are heard, ideas are voiced, improvements are made, and all of that was true for The Big Dig but it also opens this little leverage point, this little doorway that can be weaponized, right?

Nancy Solomon: Yes, exactly.

Ian Coss: That happens in the case of The Big Dig. You have some very organized local interests, most notably a parking lot owner in East Boston who is angry at the project for taking a piece of his parking lot. He said, "Nope, I'm not going to sell you my parking lot. I'm not going to give you my parking lot, you're going to have to fight me for it." He used the environmental impact statement to wage war against this project. Again, The Big Dig, it captures the complexity of how the process can really improve the project and very nearly killed it.

Nancy Solomon: We're talking about things for the public good, big, expensive projects that we need all over the country. We may never see high-speed rail, I fear, in this country because of what it would take to get it built and get it approved.

Ian Coss: I did an event of just a few weeks ago at Boston City Hall. Some of the transportation planning staff invited us, me and my co-producer, Isabel Hibbard. We went and did a talk with their transportation planners, which I had total impostor syndrome, like, "Wait, you want to talk to me about, like, you do this, this is your job." We show up, and we started-- It was really the younger generation of planners and staff that came who had heard the lore of this project. Talking to them, they're like, "I can't imagine doing something of this scale. We try and put in a bike lane, we try and take away one parking spot and it's like we're bogged down in meetings for weeks or years."

The idea of tearing down a highway, building a tunnel at the airport, like building this bridge, it was inconceivable to them. We have to reckon with that as a nation that we made it more difficult to build things for very good reasons, but we've also made it very difficult to build things.

Nancy Solomon: Yes, exactly. Oh, let's go to the phones. We've got folks from Boston calling in. Let's hear from Richard in Somerville.

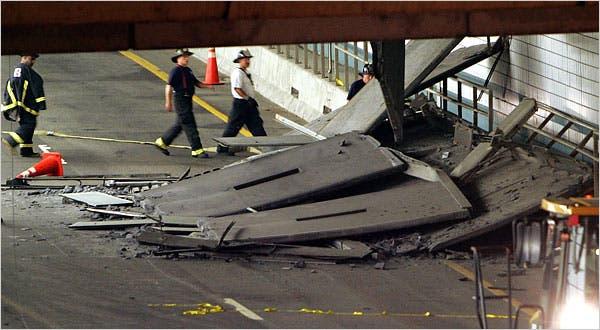

Richard: Hi there. I've lived in the Boston area since the late '70s, so I've seen this whole evolution. About 10 minutes ago, Ian mentioned how so many things that could go wrong did go wrong. I think one of the biggest examples of that fairly soon after the project finished in the Ted Williams Extension Tunnel, you might remember there was a giant ceiling panel that fell on a car and it killed a woman. She was an immigrant from Brazil.

They later on found out that the company who was responsible for the epoxy for those tiles had shortchanged the process. I don't remember if they were punished in any way. The thing that really brings it home for me is that many years later, I've got a new job, and one of my colleagues, it turns out was in the car directly behind that one, the one that the killed a woman. If my colleague had just left home, maybe three minutes faster, she might not be here now. It's just incredible to me.

Nancy Solomon: Well, and right, I think that is the story. It could have been anybody, and people really felt that. Ian, you do a marvelous job of telling the story. I'm not going to be able to come up with her name, but telling the story of this woman in the podcast.

Ian Coss: The woman who was killed her name is Milena Del Valle. She was from Costa Rica. We spoke with her pastor, a woman named Lisa De Paz. Lisa gave the eulogy at her church after Milena died. She told this powerful story about all these public officials came, people from the project came to the funeral. Everyone recognized that this was totally unacceptable, and a tragedy for the city and for the state.

The thing I still think about from that interview is, I asked her if she's still bitter about what the loss of her friend and what this project did to her community. What she said to me is that all those people there we're all victims, they're all victims of this. The people who installed that ceiling panel they were victims of this tragedy, too, and that they deserve mercy, is what she said to me, and that she prays for them. It was an incredibly emotional moment to hear that story. It was an emotional moment, I think for the city at that time.

Nancy Solomon: It seems like part of the equation is that people genuinely do feel that this was an improvement for Boston. Yes, it's tragic that it wasn't done properly, and somebody lost their life. At the other end, you get to something that people feel good about you go on a trip across town with someone in your family, and it's so much easier for him to get to work.

Ian Coss: I don't want to oversell it here. I mean, perhaps we'll get a caller who can contradict me on this, but there's plenty to criticize in the way the project turned out to. Not everyone's happy with the whole project for sure. In terms of restoring that surface area of the city, and the fact that you can walk across the Greenway to the north end, from City Hall, and get a cannoli. The fact that you can get to the airport. The fact you can get through Downtown. It has been transformative.

In raw economic terms, something-- Whenever I'd interview people who had worked on the project or been close to it they would say, "Look at the real estate development. Look at the businesses. Look at the jobs that have flowed into the area around this project." It has undeniably transformed that part of the city.

Nancy Solomon: I believe we have a caller who actually worked on the Big Dig.

Ian Coss: Excellent.

Nancy Solomon: From Kingswood, Texas, Greg, you're on the line.

Greg: Hey, Nancy. Hey. I worked on the Big Dig for about four years, and it was the most amazing project. One of the benefits not only what the gentleman was saying about being able to open up green spaces in the city of Boston, Boston is the most terraformed city in North America. Had it been rebuilt--

Nancy Solomon: What does terraform mean?

Greg: That means where human beings have rebuilt the city. There used to be a ridge of hills in the 1770s around Boston. Those were all taken down and used this field to build out the port of Boston. Anyway, the the thing I want to say, we had so many engineering students from all over the world who were apprenticed to different trades, different companies, and they float through the whole project and saw what's possible. Everyone was so excited.

There were so many complications that were handled by people just figuring it out and working through the problem. People saw what is possible on such a grand scale that we haven't seen in this country, since FDR's projects like the Golden Gate Bridge, the CCC, things like that. These are not spending money. You see the political parties who say, "Oh, you can't spend money. You can't spend money." This is investment, and infrastructure is the biggest investment with a return on that investment in the country.

Nancy Solomon: Thanks so much for your call, Greg. Ian anything you want to add to that?

Ian Coss: Well, I think what Greg's prospective highlights, for me, is just the contradictions of these projects are so wild, and that you could talk to people who were in the public just hearing about it who would-- Just to give you my sense of my personal perspective, growing up, I heard nothing but bad things about the Big Dig. Around the kitchen table, on the news, it was just all bad. Boondoggle, fiasco, debacle, pick your word, big mess, big hole, big pig, big lie. Then you talk to people who worked on it, and there's so much pride. Just like Greg was describing, there were engineering marvels that were going on, there were problems that were being solved. It contains all of that.

I remember I interviewed a foreman who worked for almost a decade on the project, a man named Frank Martinez, who'd literally go to work when it was dark out, and his kids were still asleep. He'd come home, and it was dark already, and his kids were already in bed for years and years and years. He told me how he'd come above ground and walk the streets of Boston, and he didn't want to wear the shirt, or the hard hat that identified him as someone who worked on the Big Dig because people were so furious about this project.

That disconnect between how it felt for the people who were doing it, and how it looked on the outside, it was just incredibly stark.

Nancy Solomon: Well, and I thought you made an interesting point towards the very end of the podcast about the role that reporters and journalists have played of just the gotcha finding every mistake, finding fault with everything, and how that's part of what drives the skepticism and the lack of commitment that people have to spending tax dollars on projects that are important to do.

Ian Coss: I don't intend to call out or criticize the incredibly hard-working reporters who covered the story, and I interviewed many of them for the series. I do think the story of the Big Dig makes you think about the role of journalism in civic life. Part of it is to be the watchdog and shine a light on the problems where they exist. Part of the role is to enable government to function and enable the public to understand the investments we're making.

I think the media struggled in many ways to communicate to the public the enormity of what this project was, and the problems it was having in a way that allowed us to understand them both. There's this conversation I had this night in the podcast, with a transportation reporter at The Boston Globe who covered the project in its final years. He told me, when the tunnels finally opened, it's been years and years of work, the tunnels are opening, big ceremony is coming up. The mood in the newsroom at that point was, "Go out and find something that's wrong with this thing, and don't come back until you do."

Nancy Solomon: Oh, wow.

Ian Coss: That was essentially the directive in the newsroom because at that point the public had felt misled and burned so many times by this project as it unfolded that at that point the editors were not ready to give the project that win. They were, "Find something that's wrong with it." He dutifully went out and found stories about little things that could go wrong. He told me looking back now it's like most of those stories that he wrote in that month of the opening were not actually big problems, and that in hindsight, maybe the cynicism did sink in too deep.

Nancy Solomon: Speaking as a reporter, I think that's a constant hazard of the job is that you become so oriented towards looking for problems. It's like a hammer always finds a nail we'll figure out what that's saying is, but you find the problems. I remember one of the things in the podcast was about how it was over budget. Any big project like that's going to be over budget, that's just how they go.

Ian Coss: I think part of what's important to remember too, is if you go back to the highway building era of the 50s and 60s, at that time the media was just like, 'Yes, build highways." There was no second guessing and there was no scrutinizing the details in the plans. In some ways, these pendulums swing from the media being all the cheerleaders of big public works to, by the time of The Big Dig, being very skeptical.

Nancy Solomon: Our phones are open and we'd love to have your stories and questions in this conversation. What's your big dig? I'm talking about that seemingly endless infrastructure project where you live. Call or text or tell us how it's impacting your community, just ahead on Notes from America.

[music]

Rahima Nasa: Hi everyone, my name is Rahima and I help produce the show. I want to remind you that if you have questions or comments, we'd love to hear from you. Here's how. First, you can email us. The address is notes@wnyc.org. Second, you can send us a voice message, go to notesfromamerica.org and click on the green button that says "start recording." Finally, you can reach us on Twitter and Instagram, the handle for both is @noteswithkai.

However you want to reach us, we'd love to hear from you and maybe use your message on the show. All right, thanks. Talk to you soon.

[music]

Nancy Solomon: It's Notes from America with Kai Wright. I'm Nancy Solomon, in for Kai tonight. I'm joined by Ian Coss, host of the podcast, The Big Dig from GBH in Boston. It's about a notorious infrastructure effort that earned a moment of reexamination for what it can teach us about building big ambitious things in America. Ian, another example of a very necessary project that is likely to become the next Big Dig. It's called the Gateway Tunnel, and it's the new rail tunnel under the Hudson River between New Jersey and New York City. The existing tunnel was built a century ago and is crumbling, and the entire Northeast Train network from Boston to Washington is dependent on this one aging tunnel.

In 2010, then Governor Chris Christie cut the project to build a new tunnel under the Hudson. Christie said the tunnel was poorly designed and would cost too much money.

Chris Christie: You know, there comes a point where you just say, "I can't, I can't do it, and I'm not going to do it." I'm not going to blindly go down the road and say, "Well, someone else will figure it out."

Nancy Solomon: Christie needed money to repair roads in New Jersey, and he didn't want to have to raise the gas tax to do it. Despite a design process that had taken 15 years and federal money already delivered for it, he canceled the tunnel project.

Chris Christie: This decision is final, there is no opportunity for reconsideration of this decision on my part. I am done. We are moving on.

Nancy Solomon: Christie was forced to return the federal funding, and now 13 years later the federal funds to build a tunnel under the Hudson have just been approved, and now it's going to take many, many years to build. What did we learn from The Big Dig that might tell us what to expect about getting this tunnel built under the Hudson?

Ian Coss: What did we not learn?

Nancy Solomon: Yes [laughs].

Ian Coss: One of the things that it makes me think about is that one of the ways I think about The Big Dig is as a outlier, it is the project that did get built, that did survive in an era where for many, many reasons, so many projects died on the vine. Part of what's so remarkable about it is that a project like this, or like the Gateway Tunnel, is not built by one administration. Fred Salvucci, who was really known as the architect of The Big Dig, he has this line that he said to me a couple of times. "These projects are conceived under one administration, they're funded under a second, they're permitted under a third, they're built under a fourth, and they're opened under a fifth."

That is the lifecycle of a major infrastructure project. It's measured in decades.

Nancy Solomon: All you need is a guy who needs some money for roads to get in the way.

Ian Coss: Yes, and all it takes is one person, exactly, along that years' long journey to say, "Meh, this isn't my dream, this isn't my priority. No, thank you." What's so remarkable about The Big Dig is that it was passed like a baton from across several administrations, Democrat and Republican through the era of austerity and small government and private, through the '80s and '90s into the 2000s and it survived. It's so perilous. The pathway, and I think what the tunnel project you're talking about in New Jersey highlights is that the pathway for this project is these kinds of projects is so perilous.

The moments and opportunities for them to be killed are so plentiful. That really, when you look at a project like The Big Dig, you have to look at it as a weird creature, a strange survivor that somehow navigated all that and made it to the finish line.

Nancy Solomon: Yes. Okay. Let's take another call. We have Patty in Minneapolis on the line.

Patty: Hello.

Nancy Solomon: Hi Patty.

Patty: How are you?

Nancy Solomon: We're good. Tell us what's up.

Patty: Well, we have a project in Minnesota and specifically going through Minneapolis called the Southwest LRT. It is a rail project to go out to the suburbs. It's initial budget was $900 million, its current budget is now $2.7 billion, and many of the overruns were caused by some very initial poor planning. In that, they thought that they could fit right rail and the current rail that's on there in the same narrow corridor in the City of Minneapolis.

Nancy Solomon: We've gotten a text asking us to remind folks of the size of the Big Dig. We just heard about Minnesota's Big Dig and what was the size of Boston's?

Ian Coss: In raw numbers?

Nancy Solomon: Yes.

Ian Coss: The final price tag was about $15 billion when it was done. For comparison, the earliest, earliest estimates for the cost of this project before inflation, before everything was $2.2 billion. That is the journey [laughs].

Nancy Solomon: [laughs] That's a pretty big inflation rate there.

Ian Coss: I think what the project in Minneapolis highlights and what the Big Dig highlights is, you hear these numbers that are like, oh, it started at this, it ended up at this. Started at $2 billion, ended up at $15 billion, started at $900 million, ended up at $2.7 billion. What I think is important to understand about the Big Dig, and I think this true of many other projects too, is that it was probably always going to be a $10, $12, $15 billion project.

It's not like it should have cost two or five or $7 billion and it just got really messed up along the way. It was probably always going to be expensive to do everything that we wanted to do in this project. When you look at those cost numbers, a lot of the question I think you have to ask yourself is why was it misunderstood or miscommunicated from the beginning, maybe deliberately.

There's a great a book that came out this year by a scholar named Bent Flyvbjerg, who's a Danish scholar of megaprojects. He describes in there really eloquently how politicians and public officials of all kinds are prone to, A, optimism bias, which most of us humans are, we think things are going to be easier than they are. Also, there is a built-in incentive to strategically misrepresent what a project is going to take.

Nancy Solomon: So people will support it.

Ian Coss: So people will support it. Here in New York City, Robert Moses, the legendary builder of bridges and roads, this was part of his mantra was like all you have to do is drive that first stake. Get the approval to drive that first stake, and then you're good. Then it doesn't matter how much the cost goes up, it doesn't matter how disruptive it is. It will happen. I think one of the things we have to ask ourselves as a society is, we've created a political operation for building infrastructure, in which it's so hard to get projects approved and funded. That to get a project in that door there's all this incentive to tamp down the estimates and make it look small and make it look cheap and easy, and then, okay, we'll deal with the overruns later. I think that's part of what feeds this cycle of optimism and disappointment and cost overruns because we had unrealistic expectations going in.

Nancy Solomon: Right. We have another call from Minnesota. We have Mike on the line. Hi, Mike.

Mike: Hello. How are you tonight?

Nancy Solomon: I'm good.

Mike: Good--

Nancy Solomon: Tell us about your Big Dig project.

Mike: Well, I think I have a little bit of an interesting insight on the project. I spent from about '94 till I left in '99 in Boston, and I was a bicycle messenger while I was going to school.

Ian Coss: Wow.

Mike: I was daily driving around, riding my bike around, looking to see which way the traffic was coming from in any particular day.

Ian Coss: Different every day, I assume.

Mike: Yes, they would change traffic flows every day, and of course, being on a bicycle with skinny wheels, the metal grates the metal plates that they would put down to cover holes would change all the time. You had be quite aware of what that was going on, but I just wanted to reiterate a little bit from a couple of callers ago. Dave. I believe it was, just the magnitude of what this project was and is. As an example, I had a delivery, I think I was probably on about the 53rd floor of One Financial, One Fin, and we could stow our bikes in the loading dock and get in and out.

As I was coming out of the loading dock after being up that high, I looked down and I could see maybe five flights straight down, but they had safety stuff, scaffolding and all that, so I couldn't even see the bottom of the tunnel. I look back up at the building and I'm like, that's like 90 stories tall, and within 50 feet of the loading dock there's a tunnel that you can't see the bottom of, just the feet of that. Couple that with the idea that what Market Street is between One Fin and the tunnel and what was it? 100 years ago or so Market Street was waterfront.

Basically, they're building this under sea level. It's just amazing to me that this will hold up.

Nancy Solomon: Well described Mike. Thank you for that.

Ian Coss: There were a couple of scary-sounding newspaper headlines that came out in the mid-1990s when the project was really in full swing where they realized that a few skyscrapers right next to the project were sinking just slightly. We're talking about fractions of an inch here. Still, when you're talking about a 50, 60-story building, and as Akala described, some of the foundations for these buildings are very close to the project. It's right at their doorstep, digging down 100, 120 feet right next to a skyscraper. The people--

Nancy Solomon: It is incredible.

Ian Coss: It was anxiety-provoking, I imagine, looking down from those windows.

Nancy Solomon: We're going to take another call. We have Charlie in Brooklyn on the line. Hi, Charlie.

Charlie: Hi, how are you guys? I live in Brooklyn-- Great. I actually live right next to a highway and I would love for them to demolish it or bury it.

Nancy Solomon: Would that be the BQE?

Charlie: Yes.

Nancy Solomon: Yes.

Charlie: In Sunset Park, but my story was that I worked with a bunch of conservative operating engineer guys on the Hudson River dredging job near north of Albany on the Hudson River. The guy I promised him I would tell a story that this guy said, "I dug those tunnels I would never drive through them myself." He was a pretty conservative. He was not pro infrastructure-spending kind of guy. Then the other thing was I would love if you gave a little context in terms of how this-- Did people view it as healing the city from all the destruction that Urban Renewal had done in the '50s? Maybe you could go into that.

Nancy Solomon: Like the stitching back of neighborhoods?

Ian Coss: Yes, this was explicitly that. The architects of this project saw it. It's funny actually, when the project got its federal funding, this was in the late 1980s, it was funded by the interstate program. The program that built the highways that tore the city apart. The project staff would go down to DC and they'd meet with federal officials and they'd make their presentation and make their case. What the state officials would tell me is we always had to sell it on the transportation benefits. The federal highway officials, the interstate officials were not interested in stitching the city back together.

They had this disparaging term for the project was, oh, this is just an urban beautification scheme. That was their way of saying, "Yes, this isn't really for us." If it's not destructive, it's not ours, was the way somebody paraphrased it to me. The people working on the project will go down, they'd make their case, but in their heart of hearts, they knew this was about putting the city back together. They just couldn't say that out loud. There was a real split screen I think, for a lot of people working on it.

Nancy Solomon: Maybe because that then says something about all the other highways that have been built. If you're pro-highway, you don't really want to talk about the need to take them down.

Ian Coss: Yes, it's funny you mentioned the BQE. We're doing the show from New York tonight. I was in Sunset Park today. I walked underneath the BQE. It was a reminder for me like, right, this is what Boston was like right in the heart of the city.

Nancy Solomon: Let's try to squeeze in one more call. I may get myself into trouble here. Peter is on the line from Vermont or in Vermont.

Peter: Oh, Hello?

Nancy Solomon: Hey, Peter-- We only got a couple of minutes left.

Peter: All right. Yes, I had-- In those days, I was a bike courier and also a driver in and out of the city by little hatchback Toyota from the mid-'80s to the '90s. It meant the amount of time that I spent just filing through traffic at 10 miles an hour on the old Southeast Expressway and then the tunnel made it just a breeze. You just go right, just cruise on through most of the time. I'd say it worked and apparently, that's how much that kind of thing costs and we should do a hundred more. If they built tunnels instead of redlining, and greenlining cities, we'd be in a better place now.

Nancy Solomon: Yes, there's so many neighborhoods and communities all across the country that were completely split apart. Usually, they were Black and brown neighborhoods split apart by the highways that were built in the '50s and '60s.

Ian Coss: What's interesting is, now we're seeing in the 2021 infrastructure bill that passed Congress a couple of years ago, there is money in there specifically for removing highways that divided neighborhoods. The thinking around this has not gone away. I think part of what's interesting about the Big Dig is it looms in the background of all those conversations.

If you want to tear down the BQE or whatever the interstate highway is that divides your city, the Big Dig is an inescapable reference point. I think as the caller described, it's a point of inspiration, but it also is this cautionary tale. I think it still holds that mixed legacy.

Nancy Solomon: Do you think your podcast is the first to actually make the argument that it wasn't such a boondoggle after all and that maybe we need to rethink our cynicism about these big projects?

Ian Coss: I try not to land too hard on rendering a verdict, is it a boondoggle or not? In some ways, it was a boondoggle in that it was-- To me, part of what makes a boondoggle is people feel like it's a boondoggle. It's like, if you think it's a boondoggle, it is a boondoggle. I think there's a reason why it earned that reputation but I do think what this project has is the benefit of time. There have been books written about the Big Dig.

There was obviously no shortage of ink spilt about it at the time, documentaries and all the like. I think we have the benefit now several or a couple of decades after the project was completed to see the long view of its origins, its execution, and its effects. My hope is not that people will abandon any criticism of the Big Dig, but that this will complicate whatever your narrative of the Big Dig is, whatever you thought the project was, that this will complicate that just a little bit.

Nancy Solomon: That's the perfect place to end it. Ian Coss is the host of The Big Dig a podcast from GBH news. Check out all nine episodes wherever you get your podcast. Thanks to everyone who called in tonight or sent a text particularly if you're in Boston. Thanks so much to Ian. It was great talking to you and I loved the podcast.

Ian Coss: Thank you so much. It was a pleasure.

Nancy Solomon: Notes from America is a production of WNYC studios. Find us wherever you get your podcasts and @noteswithkai on Instagram. Theme music and sound design by Jared Paul. Matthew Mirando is our live show engineer. Rahima Nasa produced this episode. Our team also includes Regina de Heer, Karen Frillman, Suzanne Gaber, David Norville, and Lindsay Foster Thomas. Our executive producer is André Robert Lee. I'm Nancy Solomon in for Kai Wright. Thanks for joining us.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.