How American Business Taught Us to to Love the Free Market

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. As Depillis explains it, greedflation is just the latest theory to run a foul of the notion that economies run best under the market's invisible hand, which is to say a system that works by supposedly spurring on individual producers to make what society needs, not necessarily to do good, but to do well. Has the American ideal of an economy left entirely in the thrall of that invisible hand always dominated?

Naomi Oreskes is a professor of the history of science at Harvard University and the co-author with Eric M. Conway of The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market. This big book traces the evolution of what she calls free market fundamentalism from a theory to America's one true faith. The fact is, planners and politicians have tinkered with the market throughout our history, putting up guardrails usually after we've crashed and then dismantling them, moving fitfully but inexorably to the religious extremism events on Capitol Hill and Fox News today.

When I spoke to her earlier this year, Oreskes said that the intensity of our belief in the myth of the free market as an invisible hand freedom shield, part of the natural order isn't an accident. It's rooted in a century-old masterfully conducted public relations campaign. Its first big challenge child labor. The free market propagandists were for it.

Naomi Oreskes: This is something I think most Americans either never knew or have forgotten how incredibly deadly and dangerous work was. This included children as young as two years old working in textile mills in Massachusetts. If a child began work in a mine or a miller factory at the age of two or five or six, the odds were very great that child would not live to see adulthood. The manufacturers claim that it wasn't really that dangerous, and they argue that child labor laws are denial of freedom, that if the government says children can't work in factories, it's denying the freedom of business leaders and the freedom of parents, particularly fathers to decide what is right for their children.

They begin to construct a story that links economic prerogatives of American big business with American freedom. That's the story that we see being built and told over and over again for the next 100 years.

Brooke Gladstone: The big PR campaign pushing back against government regulation of labor was headed by something called the National Association of Manufacturers. It was a group composed of some of the heads of the largest companies at the time, Sears, General Electric. They got together and created a campaign in support of child labor. Now pull another thread and tell me about Friedrich von Hayek, the influence he had.

Naomi Oreskes: In 1944, a group of American business leaders led by a man named Jasper Crane, who had been an executive at DuPont, and a man named Harold Leno, who was the head of one of America's first libertarian foundations, had the idea to try to promote neoliberal thinking in the United States. Neoliberalism had been born in Austria. It was developed by a group of economists, two of whom were Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek.

A group of businessmen who had in the 30s criticized socialism and communism as foreign theories actually imported a genuinely foreign theory behind closed doors, gave money to universities to hire these two men. Von Mises was hired at New York University and Hayek was hired at the University of Chicago.

Brooke Gladstone: Von Hayek wrote a famous book, The Road to Serfdom, that went on to influence Ronald Reagan and then Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh, Ted Cruz, Paul Ryan.

Naomi Oreskes: Its essential argument is that capitalism and freedom are indivisible. That if you begin to compromise economic freedom, then it's only a matter of time before you're on a slippery slope to totalitarianism. Now, von Hayek's book was written mainly in response to Soviet-style centralized planning that for government to actually plan the economy, they'd have to control the economy. They'd have to decide how much a particular factory would produce there and how many workers. They would have to control people. Pretty soon you're not just controlling the economy, you're controlling the whole society. They raised some important and interesting questions, but they then begin to use it as an argument for any government action in the marketplace. For example, banning child labor. Now, in fairness, von Hayek, he is not nearly as extreme as his later followers make him out to be. Von Hayek actually says, no, no there is an appropriate role for government. For example, there is a role for government to stop pollution and deforestation.

In the hands of his followers, it becomes a much more black-and-white argument. These same business leaders who get him hired at the University of Chicago, produce a Reader's Digest version of the book in which all the caveats is stripped out. Then they create a cartoon booklet, which is distributed through Look Magazine to millions of households all across the United States with this argument that any government involvement in the marketplace, the next thing we're living under a Soviet-style dictatorship.

Then they funded a major project at the University of Chicago called The Free Market Project to develop a blueprint for an unregulated or very weakly regulated American capitalism. One of the key components was supporting the work of Milton Friedman. These business executives funded Friedman to give a series of lectures in the United States pushing forward this idea. He turned that set of lectures into a bestselling book, Capitalism, and Freedom. It's made into a television series.

Brooke Gladstone: The National Association of Manufacturers, as you say, sponsored radio shows, most notably, The American Family Robinson, which aired around the country.

Speaker 7: ...was telling me is how you explained to him about taxes and government spending. Our people are hollering for more money to spend and then hollering about heavy taxes at the same time. I know there are a lot of folks who don't seem to realize that all this money has to be taken out of the people's pockets by the government.

Naomi Oreskes: The American Family Robinson was a radio program that was designed to be propaganda.

Brooke Gladstone: That was the word that NAM officials used in their documents to describe the program.

Naomi Oreskes: Correct, designed by NAM to propagandize the values of big business and the threat of the new deal.

Brooke Gladstone: How?

Naomi Oreskes: Through stories in which the government interferes in ways that damage people's businesses, through speeches given by characters about how the American way is to stand on your own two feet, how government involvement threatens the primacy of the nuclear family, distributed free of charge to hundreds of radio stations around the country. It ran for many, many years, would've been heard by millions of Americans.

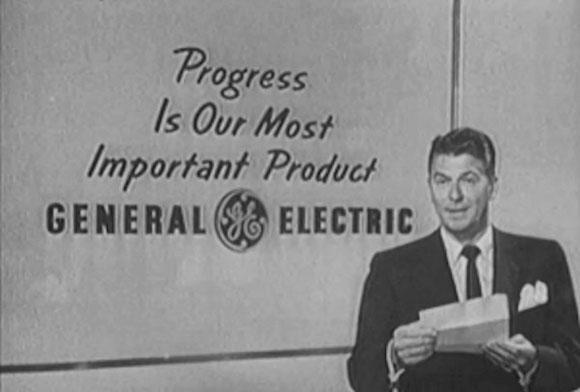

Brooke Gladstone: There was also a TV show hosted by none other than Ronald Reagan.

Naomi Oreskes: Ronald Reagan is a really important part of the story of how these views which up until the 1950s are decidedly not mainstream, become mainstream. Most Americans know that Ronald Reagan before he was a politician, was an actor. What they don't know is that his acting career was pretty much on the skids in the mid-1950s when he was recruited to be the host of a television program called General Electric Theater, which under Reagan became the third most watched television show in the United States in the late 1950s.

It was a high-quality program with good actors. There's one episode starring Harry Belafonte. They all began and ended with little didactic introductions or conclusions about individualism, standing on your own two feet and not relying on government.

Speaker 8: You expect something from liquor that liquor was never intended to do for you, like helping you cope with the lousy breaks of life. Therefore, it becomes a moral issue, not to take that first drink.

Naomi Oreskes: Hosting General Electric Theater was only half of Reagan's job. The other half was going on the lecture circuit on behalf of GE to promote a very anti-union, anti-government, pro-market ideology. He would give talks in factories, in schools. He would go to the Rotary Club or the Lions Club in the evening and present this set of arguments.

Now, we don't know exactly what happened inside Ronald Reagan's head, but what we do know is that he went into General Electric, a pro-union, New Deal Democrat, and he came out an anti-union, anti-government Republican.

Brooke Gladstone: The National Association of Manufacturers is still going full swing. Right?

Naomi Oreskes: NAM still carries quite a lot of weight in Congress because there still are millions of American workers in manufacturing. They have been a major force lobbying against climate change litigation and trying to block the SEC from having disclosure rules regarding conflict minerals.

Brooke Gladstone: You've suggested that all of this messaging is intended to reduce our options to either capitalism without regulation or repressive communist dictatorships like those of the Soviet Union or China.

Naomi Oreskes: A lot of the propaganda and also the academic work done by the Chicago School presents this as a dichotomy over and over and over again. That's a false dichotomy. There are lots of choices. We do have all kinds of regulations about eight-hour work days and being paid overtime. It's been hard for us to have that conversation about the right choices because we've been so bombarded with this false dichotomy of, laissez-faire economics, unregulated markets, the invisible hand versus we give up all our freedom. Next thing we know we're facing a firing squad.

Brooke Gladstone: Some Western democracies, notably in Europe, seem to have found a middle ground without giving way to soul-sucking authoritarianism.

Naomi Oreskes: They're still fundamentally capitalist market-based systems, but they have stronger social safety nets, stronger protections for workers, stronger protections for the environment, in many cases, stronger protections against dangerous products like endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Yet, these countries are prosperous. They are democratic. Actually, by some measures, they're actually more democratic than the United States.

Brooke Gladstone: How are they more democratic?

Naomi Oreskes: Just look at things like to what extent policies reflect what public opinion polls show the people of that country actually want. We know that here in the United States that many of our national policies don't reflect what a majority of Americans would like to see happen. Of course, we're facing massive efforts at voter suppression here in the United States, various kinds of corruptions formed by the lack of controls on campaign financing. France elections are only allowed to last for a certain number of days.

Brooke Gladstone: Now, part of the myth of the market is that government intervention doesn't work, and you say that you can easily disprove that by considering the economies of individual states today.

Naomi Oreskes: I moved to Massachusetts from California, and I can tell you that I think Massachusetts does have a bit of a nanny state mentality. I have personally been sometimes frustrated by the fact that I can't buy a decent bottle of wine on a Sunday. The reality is that Massachusetts is one of the richest and most successful states in the United States, has extremely high levels of education and relatively low levels of a lot of the social ills that plague other states. Regulation works. Public education works.

High levels of taxes work if you invest them in education and infrastructure, which Massachusetts does.

Brooke Gladstone: The Human Development Index that was developed by the UN as a counterweight to the GDP to try and track how people are faring in terms of health, education, life expectancy, standard of living. Massachusetts ranks number one on that scale, and it's closely followed by Connecticut, Minnesota, and New Jersey. In contrast, the bottom eight tend to be states more hostile to big government, Mississippi, West Virginia, Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Tennessee.

Naomi Oreskes: What these data show is that the states that have high levels of taxation and highly engaged governments, people are doing better. States like Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, that are hostile to government and have low levels of taxation, people are doing worse.

Brooke Gladstone: One of my favorite things is the exception that proves the rule in this case, which is Utah.

Naomi Oreskes: Utah is interesting because Utah is a very red state. It has very low levels of taxes, but it's economically successful. It turns out one of the many things that it's doing right is being a large recipient of Federal government funding. A lot of the booming in Utah in the last 20 years was because of the growth of what's called the Silicon Slopes. Salt Lake City was one of the original nodes in DARPANET, which was the federal government precursor to the internet developed by the US military to support military communications.

It was out in front when DARPANET became commercialized as the internet. Because of a major government program, Salt Lake City was way ahead of the curve when the opportunities began to develop the tech industry.

Brooke Gladstone: But there's more. The Salt Lake region, you said also proved attractive to young professionals because of its easy access to great outdoor recreation, particularly its world-class skiing, all of which takes place on federally protected land.

Naomi Oreskes: Some of the best skiing in the world, beautiful hiking, and all of that was developed on federally protected lands. Then, it turns out, because Utah is considered an agricultural state, many residents can get federally subsidized mortgages through the Department of Agriculture. Example, after example, after example, what we see is that so-called small government doesn't yield the prosperity, the economic outcomes, or the health and well-being for people that its advocates promote.

Brooke Gladstone: The 2008 financial crash would be even further proof that government regulation is necessary. Let's return to that spectacularly influential Chicago School. Its jurist and legal scholar Richard Posner changed his free-market notions after that crisis when he saw that self-regulation didn't work, at least in financial markets.

Naomi Oreskes: Posner was one of the leading proponents of the Chicago School of Law and Economics, a big advocate of deregulation, of allowing markets to mostly operate on their own, but after the 2008 crash, he says, "Look, these guardrails were put in place to prevent the economic system from crashing. When we took them away, the system crashed because self-interest doesn't actually work to protect the common good, because what's in the interest of a person as an individual may not be in the interest of society as a whole."

I think what he's written is very courageous, but it's amazing to see how little influence it has had in so many other people who are still sticking to the Chicago story.

Brooke Gladstone: Now, let's talk about the stakes, Naomi, what you call the high cost of a free market. Start with climate change.

Naomi Oreskes: Climate change is one of the clearest examples of market failure that we've seen in our lifetimes. Nick Stern, the former Chief Economist of the World Bank, has called climate change the greatest and most wide-ranging market failure in history. Because oil and gas, and coal are legal products, people have used them to do legal things, but in the process of doing that, they have created this giant external cost that accrues to people irrespective of whether they did or didn't use those products.

Now, we're looking at trillions of dollars in damages from climate change, and who going to pay that bill? Well, all of us. People in Bangladesh, people in Pakistan, it's a market failure because the market doesn't account for the true costs of using these products.

Brooke Gladstone: Let's talk about happiness.

Naomi Orskes: What we know and the evidence is very, very clear now is that Americans are actually very unhappy. Money has not bought us happiness. Overall, the happiest people in the world are the ones who live in the European social democracies because those countries have a few key things, good social safety nets, so you don't have to have tremendous anxiety about what will happen to you if you get sick or if you lose your job, better distributions of income.

They don't generate the resentment and frustration that we have here in America and they have healthcare because it's hard to be happy when you're not healthy. They have trust in institutions which is the most interesting of all because if you ask yourself, well, why don't Americans trust our institutions? Well, one of the big reasons is because we've been subject to a century-long propaganda campaign telling us not to trust our most important institution which is government.

Brooke Gladstone: Finally, freedom. In your conclusion, you wonder, did the men and women in this story really believe in liberty?

Naomi Oreskes: America was capitalist in the 19th century and we had slavery. America was capitalist in the 20th century and until 1918, women didn't get to vote. America's capitalist today and millions of people are incarcerated. Freedom is something we fight for. It's something that we protect with our political and civic institutions and the idea that we can somehow protect our freedom by letting business people do whatever the heck they want, it's refuted by the facts of history.

This is why this question comes up about whose freedom were they really trying to protect. Ultimately, the people we studied were trying to protect their own freedom, their own profits but they constructed a myth about the defense of political freedom because they knew that if they said, oh yes, I'm working to protect my profits. There's no reason why any of us would've bought that story. Nobody wants to be a sucker and in a sense, we've been suckered by the market fundamentalism narrative.

Brooke Gladstone: Naomi Oreskes is the co-author with Erik M. Conway of The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market.

Naomi Oreskes: Thank you very much.