A Historian's Guide to the 2020 Election

Kai Wright: I'm Kai Wright and this is The United States of Anxiety, a show about the unfinished business of our history and its grip on our future.

[crowd protesting]

Speaker 1: The foundation of our democracy has always been skewed towards one group over another.

Speaker 2: 1619 is as foundational to the American story as here, 1776.

Speaker 3: It is a privilege to become an American, not a right.

[crowd protesting]

Speaker 4: There are some people who are not willing to be physically violent, but there are some people who are willing to strip you of your rights and vote in violent ways.

Speaker 5: I have children. I'm 27 now. I don't want them at 27 fighting the same fight that I'm fighting. Just a little bit different than my ancestors fought.

Speaker 6: This almost feels like the 1850s.

[music]

Kai: Michelle Obama had this line in her speech at the Democratic National Convention. She said, "If you think things cannot possibly get worse, trust me, they can and they will." She was really teeing up her "Get out to vote" pitch, but it's been just like a month and a half since then. It already feels more like a prophecy. Anyway, what it really brings to mind for me is a common misunderstanding about the cycles of change in the United States. People talk about the political culture as a pendulum that swings back and forth. I think it's a lot more useful and may be more urgent to understand it as a tug of war. This week, with certainly the most consequential election of my lifetime, just 37 days away, we're going to unpack something historian, Eric Foner said to me earlier this year.

Eric Foner: Slavery was 250 years more or less. We're only 150 years past the end of slavery. These ideas of power, of racial inequality, of domination, are baked into the culture. That's why when people ask me when did reconstruction end? I said it hasn't ended. [chuckles] No, we're still fighting over these reconstruction issues.

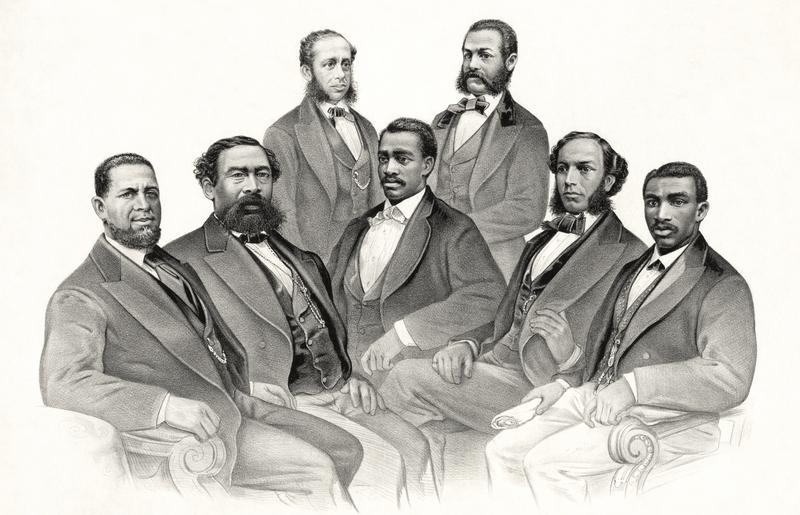

Kai: Reconstruction. He's talking about the years following the civil war in which Americans tried to rebuild and re-imagine this country without slavery. It was a time when Black achievement exploded in every part of life, not just politics. There were more Black people in Congress in those years just after the war than in a whole next 100 years. I am a real geek for this history and earlier this year, we dedicated most of our show to making connections between that time and this one. I do have to admit, there has always been some real skepticism on our team about my enthusiasm for this history. Here's how our Senior Producer, Veralyn Williams, put it to me.

Veralyn Williams: It was just a moment where you built it up to be like America was actually living up to its ideas of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I was at the time like-- I don't remember that history because what I remember is very early on in my life [unintelligible 00:03:16] my cry, which is about a family in Mississippi who were sharecroppers-

[background audio]

-dealing with racism and being terrorized within their daily lives.

[background audio]

The images that I have of Black people in this country since slavery, none of it was aligned with what you were describing.

[background audio]

I was skeptical and that's maybe the kindest way I could describe what I was. When you have a clear understanding of racism, it's like I'm not-- I think I'm being lied to. I think I understand--

Kai: See, this is what I was trying to say. It wasn't utopia, but I think the lie that we've been told is that this time didn't exist. The whole Southern project after reconstruction was this effort to erase it from our memories. I feel like it was successfully erased from my education. I have this fancy education and it was erased from it. As an adult, I have had to reinsert it. Once I know it, it changes everything about what I understand about what is possible in this country and what is possible for Black people.

Veralyn: I think the other thing that I've thought a lot about is it still wasn't quite great for Black women. Maybe that had a lot to do with my ability to reconcile that things were great because like, "Great for who?"

Kai: That's a really big part of the debate during reconstruction. Who are we talking about when we start talking about freedom? Who's all encompassed in that? I think what is so interesting about it and that I still argue-

[laughter]

-all these months later, since we started this conversation is that there were a set of ideas that were being put on the table at that time about what America could be. It started this debate that we've been in ever since and that it just feels right now this election, it was clear to me back then. It's so clear now. This election is about the ideas that got introduced during reconstruction and it's like a referendum on whether or not we want to move forward with those ideas or finally actually abandoned them to the [unintelligible 00:05:47].

[music]

Eric: Before we start, do you prefer-- I can talk about this stuff at any length. Do you prefer succinct answers or should I ramble on and then figure you'll edit it down the road or what--

Kai: Give us the middle ground. [chuckles]

Eric: Yes, all right.

Kai: This is Eric Foner again. He's the author of a book called The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution. He's really the established expert on this period. Eric is going to tell us the story of reconstruction. It's the story of what could have been and maybe what could still be.

Eric: I'm not talking about utopia on Earth, but just imagine that the new deal with Black people voting in the South where you didn't have these white supremacists who controlled the levers of Congress and FDR had it. He didn't care that much about civil rights, but he had a deal with them. You want to get things through-- You want to get social security through, you got to keep Blacks out of it. You want to get fair labor standards through, you got to keep the Southern [unintelligible 00:06:54], "We're for all this stuff, but we're not going to do anything that'll help Black people get alternative modes of employment or education or something."

That was baked into the whole new deal welfare system because that was the only way to get those things through Southern segregationists. Now, if they weren't there if you had just ordinary members of Congress, voted in by Black and white people, we'd have national healthcare now. I'll tell you that much.

Kai: Many things would be different today had the story of reconstruction unfolded some other way; how we vote, how we think about the federal government, just how we share public space. All of this and more, it was determined by three constitutional Amendments; the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. Eric walked me through the story of each one, starting with the 13th, which began a conversation about what freedom actually means in the United States.

Eric: All right. 13th Amendment Section 1, "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

Kai: These seem like quite clear words, but they were not too many at the time.

Eric: No.

Kai: Let's try to parse a little bit what everybody thought they meant.

Eric: Slavery is a total institution, you might say. In other words, it's a system of labor. It's a system of politics. It's a system of race relations. It's a tremendous accumulation of wealth in the hands of slave owners. When you say slavery shall no longer exist, it's abolished. All sorts of people have different ideas about what that means. Yes, African Americans certainly understood that it meant access to the rewards for your labor that you didn't get under slavery, but they also thought it meant many other things.

African Americans had a very broad idea of what-- "We are now citizens," they said. Even though the word citizen doesn't appear in the 13th Amendment, we should have the right to vote now. At least men should have the right to vote. That's part of what it is to be a free person. Then there were many others. Southern white said, "All right, all right. They understood. No more slavery. We cannot buy and sell people anymore. That's clear, but that doesn't mean they have any other rights. We're not going to let them vote. We're not going to let them hold any power in the South. They got to go back to work for white people and now they'll be paid some meager salary instead of being slaves."

Slavery is created by state law, not by the federal government, and this amendment abrogates all the state laws establishing and protecting slavery, but it leaves a vacuum. Then what? That's the question that has to be answered.

Kai: If Black people had an expansive answer to that question and Southern whites had a very limited answer, the Northern liberals, led by the Republican Party back then, they split the difference. To them, freedom was about the market place.

Eric: That's how Northern Republicans saw it that we are going to have to give African Americans the wherewithal, the rights, the ability to do what they thought white people do all the time. That is work hard, accumulate some money, buy [unintelligible 00:10:16], set up a shop, set up a farm, move up the social scale.

[music]

Veralyn: Black people were supposed to just be able to do all that straight out of slavery?

Kai: [laughs] Pretty much. Like, "Well, we think you could-- We're freeing your freedom but that's you on your head."

Veralyn: "You're no longer slaves. Why can't you just get it together?"

Kai: Veralyn Williams, one of our producers is with me as we listened to Eric tell the story of reconstruction. I got to say, one of the super inspiring things to me about this era is that many Black people did in fact walk off of plantations and just get at it. I think what's interesting about this moment in history is like it is an interesting moment in the history of white liberalism because Lincoln was the head of that part of the party that was saying, "Okay, y'all can be free. You just need to go back to work and everything. You don't need to do anything else." His Vice President, Andrew Johnson, takes over. These two weren't allies, right? Johnson is really a Donald Trump figure. He was so reactionary and he pushes the white liberals way past where they ever intended to go.

Veralyn: Meaning getting them to be more progressive?

Kai: In reaction to him. He's so reactionary and so much. He's such a-- He really is a Trump-like figure. He's so racist. [chuckles] The white liberals are like, "Whoa, hold up."

Eric: Johnson was deeply racist. He was a white southerner who had been put on the ticket with Lincoln. No one thought he'd become president. Anyway, by the time Congress meets in December 1865, Johnson says, "All right. Reconstruction is over. 13th Amendment is ratified. I have set up Southern state governments and they're functioning so that's it. We've reunited the union. This is great."

Congress, the Northern Republicans said, "No, wait a minute, wait a minute." First of all, the government that Johnson established have given no rights whatsoever to Blacks. They've passed these very discriminatory laws called the "Black Codes" putting Blacks back in a condition, if not slavery, then something as somewhat close to it. They say, "No. Congress has got to intervene to protect the basic rights of these former slaves." What are those rights? The Civil Rights Act of 1866.

Kai: The Civil Rights Act of 1866 is a huge turn in US history. It's the first effort to operationalize the 13th Amendment. To codify what it means to be free of slavery. To me, it's really the beginning of the political fight we are still in right now. Everybody was drawn into the congressional debate over this new law. Think about it like the way Obamacare got us all talking in these new detailed ways about our healthcare system. How everybody just suddenly had opinions on the subject. That was the national conversation about civil rights in 1866. People were reconsidering fundamental questions. Who gets to be called American? What rights come with that designation? Civil Rights Act was the first law that tries to spell it all out

Eric: The right to own property, the right to go to court to sue, to be sued, to sign contracts. The right to have the law apply to you the same as to other people. Not the right to vote. There was a sharp distinction in people's minds between civil rights and political rights. You can be a citizen and not have political rights. After all, women were citizens and they couldn't vote. It doesn't include the right to vote but it does include a notion of legal equality, particularly, in trying to earn the fruits of your own labor.

It's the first law in America that tries to really establish a legal equality between African Americans and white people. Before the civil war, there was no such thing as that. Every single state had laws discriminate North and South, had laws discriminating against Blacks, and remember in 1857, the Supreme Court had declared in Dred Scott that no Black person can be a citizen. Citizenship is for whites only. Now, this is reversed. Now, anybody born in this country, Black or white whatever, is a citizen of the United States with basic rights that the federal government has an obligation and the power to protect.

Remember, the 13th Amendment had that second clause. Congress shall have the power to enforce the end of slavery. This is what they think they're doing. This Civil Rights Act is passed under the 13th Amendment. It's part of the abolition of slavery. It delineates what rights you need to have to be a free person in America.

[music]

Kai: Up next, Congress tries to make these ideas about freedom, permanent. In the process, rights are probably still the most contested words in our constitution. We'll be right back.

[music]

Welcome back. This is The United States of Anxiety. I'm Kai Wright and this week, we are not looking at the breaking news that's happening around Trump's tax returns. Instead, we're taking a step back from the news cycle and we're telling the story of a period in US history that I think you have to know well if you're going to understand any of this current political crisis.

We're looking at the years following the civil war when an interracial political coalition we imagined what the United States can be, a true multiracial democracy. I personally find a lot of inspiration in this era but also, as a Black person in this country, my relationship to any national history is of course complicated. I've been in conversation with our producer Veralyn Williams about that complexity.

Veralyn: It's hard for me sometimes to be able to just cheer on or even just articulate what's good about this time in history that we're talking about because it's like my fundamental response is always just like, "Well, look at what we're still dealing with today."

Kai: I guess for our first off the answer--

Veralyn: I guess you just want to hold onto it and you're saying it's important to hold onto it, but--

Kai: No. It's important to hold onto it and it's also like-- because I'm trying to think about the way forward. I'm not worried. I think I am not invested in the idea that we need to prove that America is rotten. I got that. I'm invested in the idea of "How do we get to Black freedom?"

Historian Eric Foner is our guide this week. He's the author of The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution among many other books. He's telling us the story of three constitutional amendments that redefine the United States. We've gone through the 13th Amendment that got rid of slavery, but it begged the question of what freedom actually means, at least legally. Congress answered that question by writing the 14th Amendment.

Eric: 14th Amendment which was approved by Congress in the middle of 1866. Section 1, "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside." Then it goes on to say, "No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."

You could spend a lot of time parsing that language. Law professors have gotten rich writing the articles and going to court and other things trying to figure out, "What do these phrases mean?" Remember, the Civil Rights Act had listed specific rights. This doesn't give you specific rights. It gives you general principles, equal protection, due process, privileges, and immunities. All of these cry out for definition.

Over the next century and a half, a lot of the work of the Supreme Court has been giving meaning to these phrases. Every single session of the Supreme Court has cases relating to the 14th Amendment. Some of the most important decisions of the past 50 or 75 years have been 14th Amendment decisions, whether it's Brown vs Board of Ed or a one-man-one-vote or gay marriage or abortion rights. All these rights come out of the 14th Amendment and those phrases of equal protection due process. Many of them, obviously, are things that people in 1866 weren't thinking about.

The members of Congress weren't thinking about gay marriage, but it's a perfectly logical use of the notion of equal protection of the law to say, "Hey if heterosexual couples get married, it's a denial of equal protection if you say gay couples can't get married." These principles have a life of their own and there's also nothing about race in this Section 1. It applies to everybody. It's a national principle. Its main purpose is to protect the former slaves but that is not the only purpose.

Kai: Let's back up and try to parse out the meaning of the words in the 14th Amendment ourselves. Let's start with the very first sentence. Here it is again.

Eric: "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside." This is birthright citizenship. The Civil Rights Act already had that, but a law can be repealed by the next Congress. This is putting birthright citizenship into the constitution for the first time.

Kai: Help us understand-- this is an idea that had not existed in human history.

Eric: It's very vague. That is to say, who is a citizen varies enormously from nation to nation, and in the United States before the civil war, it varied from state to state. Each state could determine who was a citizen. There was no national standard. Today, this is a very unique thing. No European country has automatic birthright citizenship now. If you are the child of a Turkish guest worker born in Germany, you're not automatically a citizen. You can become one. You have to go through a whole rigmarole of tests and all this. Some Latin American countries do have birthright citizenship. We're not the only one, but it is fairly unique in the world today and of course, it's totally controversial.

President Trump has voiced the idea that he could just aggregate this by executive order. Senator Lindsey Graham has called for congressional hearings on whether to change the 14th Amendment. What they're talking about, of course, are the children of undocumented immigrants, but the language is very clear. It's not about the parents. It's about being born here.

Kai: At the time, that was part of the point, right?

Eric: Yes.

Kai: Was to get rid of slavery laws.

Eric: Absolutely. Absolutely. That this is a statement that race will no longer be a determining factor in whether you're a citizen or not, which is actually a pretty remarkable thing two or three years after the end of slavery. Now, one thing I want to emphasize is that the key figures in Congress who passed all this were veterans of the Anti-Slavery Movement and the Anti-Slavery Movement for years before the war, had been insisting, free Black people must be recognized as citizens.

Free Black conventions before the civil war called themselves Conventions of Colored Citizens. Citizens, they put that right up there. They claimed it, even though the courts and political system didn't recognize it, but they were fighting for the recognition as citizens. This stuff didn't come out of nowhere. It comes out of a long struggle that Black and white anti-slavery people have been waging since the 1820s, '30s, '40s, et cetera.

Kai: It's not [unintelligible 00:22:47] explicitly about finally settling the question, everybody is a citizen in the United States.

Eric: Yes, exactly. Settling it forever. Of course, it's still open it away though.

Reporter 1: A week before the mid-term elections, President Trump said he could end so-called birthright citizenship with a stroke of his pen.

Mike Pence: We are looking at action that would reconsider birthright citizenship.

President Trump: A person comes in, has a baby, and the baby is essentially a citizen of the United States for 85 years with all of those benefits. It's ridiculous.

Reporter 2: The president said he might use executive order, his solo authority to eliminate the principle of birthright citizenship which means [inaudible 00:23:26]

Kai: The other thing that is introduced here that I think people don't realize and-- This is the first time equality is introduced into the American [crosstalk] conversation at all.

Eric: Equal protection. Of course, all men are created equal. That's in the declaration of independence. It doesn't have legal force, but it's an ideal which people paid tribute to but certainly, the legal system before the civil war was not based on equality in the slightest. The rights of women were very different from the rights of men. The rights of Blacks were very different from the rights of whites. The rights of employers were very different from the rights of employees. There was inequality shot through.

The whole question of rights is very complicated. Before the civil war, most people, certainly most white people, is said, "They're here. There are gradations of rights." There is natural rights, which are those enumerated in the declaration or life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Everybody is entitled to those; Blacks and whites. That's just by being human you are entitled to life, liberty, which means slavery is wrong, and the pursuit of happiness, which is the ability to get ahead in the market or something.

Political rights are completely different. That's conventional. The majority can determine who has political rights, who doesn't, women can't vote, but they're citizens and most states didn't allow Blacks to vote, North or South, before the civil war and they didn't think there was any illogic to that. They can have their natural rights. That's what Lincoln in the Lincoln-Douglas debates said. "Yes, the declaration includes Blacks. They're entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness but I'm not in favor of them voting. I'm not in favor of them holding office and I'm not in favor of them marrying white people. That's social rights. That's another category," which was a vague term which included individual interactions between people.

Do Black people have a right to forced closeness to whites? They have a right to get on a train and sit down on a seat next to a white person but in reconstruction, these concepts of rights go through a metamorphosis. People are debating rights up and down the society. The end of slavery shatters all these old ideas in a way and now people are trying to pick up the pieces and figure out what are the consequences of the end of slavery for the interactions of the American people with each other.

[music]

The 14th Amendment makes the constitution for the first time a vehicle that Americans can appeal to if they feel they're being denied equality.

[music]

Kai: That's part one; introducing equal rights. Part two focuses on the one right that was, and I would say it still is, the most controversial one of all; the right to vote. You got to remember the context here. The civil war had just ended and a lot of people in the North were just scared of doing anything to break up the union again. The most moderate Republicans-- The Republicans, they were the liberals of the time, the reverse of today. The most moderate of them, they wanted to give Black men the right to vote without overly antagonizing former slaveholders. That means Congress crafted this scared, convoluted language that they hoped wouldn't trigger a huge backlash from the South. That became the 14th Amendment's bittersweet second clause. It's incomprehensible but I want to try to just explain it as clearly as we can.

Eric: All right, go ahead. If you could explain it, I give you a silver dollar. Black suffrage was the big dividing line in Congress among Republicans. You have radical Republicans who say, "We got to give Black men the right to vote." Sadly, women can't vote anywhere at this time in the United States so we're talking about Black men. Why do we need Black men voting?

Actually, Thaddeus Stevens, he gets up early in the congressional session. He says, "Yes, Black men must vote. Why? Number one, it is right. They're citizens. They should vote. All right. Number two, it will keep the Republican Party in power. Three, it will keep these rebels out of power in the South. If Black men can't vote, the old Confederates are going to pour right back in and control everything." There's another weird little complication. The end of slavery ends the three-fifths clause of the constitution. Before the war, representation in Congress is based for each state on the free population and three-fifths of the slave, of the other person, as they're called. Now, there's no more slaves.

Kai: Black people in the South are suddenly going to be counted as full entire human beings, five-fifths. This will dramatically increase the official population of Southern states.

Eric: Which means the Southern states will actually get an increase in their number of members of Congress. That doesn't seem like the Republican who says, "We don't know." They don't want to do that, to give them more power. The compromise is, the 14th Amendment doesn't give anyone the right to vote. It's still a state matter, state by state who can vote. If a state does deny any group of men the right to vote, then they're going to lose some of their congressmen. Let's take Alabama, it's about 50% Black, 50% white. Alabama can decide who votes but if they say, "Forget it. Blacks are not voting," they're going to lose half their congressmen. Now, this was never enforced. Let me just show you this.

Kai: At this point in the conversation, Eric reaches across the table for the text of the 14th Amendment and he reads out the one clear part that's buried in all these complicated ideas. The fact that states are supposed to lose congressional seats if they suppress votes.

Eric: It's supposed to be automatic. "Shall be reduced." "The basis of representation shall be reduced." It doesn't say, "Maybe reduced." It doesn't say, "We'd like it to be reduced." "Shall be reduced." It is supposed to just happen. Never enforced-

Kai: To this day.

Eric: -to this day. Here's another way this relates to the present. Voter suppression. I'm trying to start a little club to enforce the second section of the 14th Amendment against Texas. Texas has 30 some odd congressmen. All you would need would be to suppress 3% of the voters and they should lose a member of Congress and they have. Texas has excluded a whole lot of people from the voting rolls so have other states; Florida so is North Carolina. Georgia went through a whole culling. Some of these states should lose a member of Congress.

[music]

Kai: This feels like, for me, this complicated section of the 14th Amendment. Feels like such an important turning point in the success and failure of the American project.

Eric: Yes, they missed a big opportunity here. I think you're right. This is what Thaddeus Stevens said when he was the floor leader in the House when it came to the final vote. He gave this great speech in which he said, "We have an opportunity here to create the perfect Republic and we've blown it. Why do I vote for it?" Then he says, "Because I live among men, not among angels."

Kai: It's just so interesting because this is the moment, as we've discussed up until now, where these principles are introduced into the American idea. These principles that we take for granted now as this is what America is about. It's also the moment where we decided not to fully go to those principles. That just feels like the rest of American history.

[laughter]

Eric: We've been living that problem forever. I agree with you.

Kai: I got to admit, this is where I totally agree with Veralyn, our producer, who's not been fully inspired by this history. It's just maddening that despite all these words in our constitution, still right now, one of the biggest questions in our current election, is whether every Black person who can vote will actually get the chance to do so. It really just makes you throw up your hands. Yet at the same time, I still share Eric's enthusiasm for the ideas in these amendments, and how much radical potential they still have.

[music]

Eric: All of them have flaws. Some of them have serious flaws. But it's an effort, a halting effort, an incomplete effort to really make the constitution a bastion of equality for the first time. The original constitution doesn't really say very much about the rights of individual Americans in their day-to-day lives. The whole Bill of Rights was considered only to restrict the federal government from interfering your civil liberties. States could do whatever they wanted. Most people's interactions with government came at the state level, not the federal level. You had a chance to really remake the constitution, and they do it up to a point but as you say, not fully in tune with principle.

The Southern states reject the 14th Amendment altogether. Even though it's so imperfect, they say, "Forget it, this will lead to Black suffrage, this whole business of equal protection of the law, forget it."

Kai: That's a bit of a wake-up call.

Eric: Yes, it shows you you cannot expect cooperation from white Southerners, basically. That's what they conclude.

Kai: The Southern states, these governments that are still controlled by essentially the same people who fought to keep slavery. They say, "No, we're not going to do what you say." Congress has to keep escalating the fight. They realize that the only way forward is to replace those governments altogether. Am I being too reductive to say that then they recognized that the only way to change the governments in the South is to do it at gunpoint?

Eric: In a sense, they say, "There are no longer functional governments in the South. These governments are no good. We're going to have to create new governments and to do that, we're dividing the South into five military districts. The army will register people to vote, Black and white. The army will make sure that you have fair elections." It's a temporary military thing because the purpose is to create new functioning civil governments.

In a sense, as one guy says, "The Congress was setting the clock back to Appomattox. [chuckles] We blew it. The first time around, we didn't really get reconstruction going properly. We're going back. The army is still in control and now what do we do to get functional government going and the only way to do that is to really create interracial democracy in the South.

In 1867, a remarkable year in American history, which people don't really recognize as such, tens of thousands of African American men, most of them slaves a few years earlier, are now going to political meetings, hearing political speeches, registering to vote, voting, something like 80% or more percent of the eligible voters pour out to vote in the Black community. This is an amazing transformation of what the political system is in the United States.

Kai: Of course, not all of the United States. Not yet.

Eric: Here's an irony. In 1867, Blacks were voting throughout the old Confederacy. They're not voting in New York oddly. They're not voting at all in Pennsylvania. They're not voting at all in Illinois. Blacks get the right to vote in those states with the 15th Amendment. "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude."

If you look at that language, what's interesting and striking, it doesn't actually say who will have the right to vote. It just says you cannot deny people the right to vote because of race. There are plenty of other grounds you could deny people the right to vote, which are not mentioned here; poll taxes, literacy tests, understanding clauses. Those are what would be used when the South did disenfranchise Black voters. Registrars would say-- guys trying to register, "Tell me what's Section 42.3 of the state constitution is. You don't know? You can't vote." It put voting in the hands of these local registrars who were all racist Democrats. That was a weakness of the 15th Amendment

Kai: And not a coincidental weakness. Can you explain the political debate at the time as to why they wrote it that narrowly?

Eric: Yes, there were members of Congress who said, "No, we want a positive amendment. All male citizens 21 years old can vote." If they had passed that, it would have solved a lot of problems later on and including today. No, the fact is that every state regulated its own voting rules. There were Northern states who were perfectly happy now to let Blacks vote in the South or in their own state, but didn't want others.

California said, "I don't want these Chinese voting." In fact, California, Oregon voted against the 15th Amendment because they were afraid it would somehow allow Chinese immigrants to vote. Rhode Island had a property qualification for voting for immigrants, not for native-born people, for immigrants. They didn't want to give up that right. There are some other prejudices. Anti-Chinese, anti mostly Irish, Roman Catholic immigrants, weakens the 15th Amendment--

Kai: Not in the South, but in the North and in the West.

Eric: The North had its own restrictions on the right to vote. It's a combination of class, religion, ethnicity, race, but the tradition of each state determining its voting qualifications was pretty deeply rooted.

Kai: To this day, there isn't a right to vote [crosstalk] in the United States?

Eric: Not a positive right to vote. There was nothing in the constitution that says who shall vote. There are many, now, clauses that say, you can't stop people voting for this reason; race. You can't stop people from voting because of sex now; 19th Amendment. You can't have a poll tax for voting. You can't stop them from voting when they're 18 years old, but as to who can vote, as we've seen, people have been struck off the voting rolls all over the country. These voter suppression laws. The right to vote is still a very highly contested thing in this country, even though your man and woman in the street would say, "Hey, that's what democracy is all about."

Reporter 3: The US Supreme Court has now overturned a lower court's ruling on how Ohio purges its voter rolls.

Reporter 4: More than 300,000 inactive voters are set to be removed from Georgia's voter registry--

Reporter 5: As its removals, are likely to affect the most vulnerable.

Reporter 6: Many of them racial minorities and poor people who tend to back Democratic candidates.

[music]

Veralyn: Hi. Okay. [chuckles] Let's go over all the good things. All the things that are good about this time. Slavery ended, that's one.

Kai: Slavery ends and not a small matter.

Veralyn: Sure.

Kai: That's now in the constitution, you cannot have slaves. Two, we have established an idea of national citizenship and everybody is a citizen if you're born here. Black people before that weren't citizens, now we are. We've established the idea that if you're a citizen, you are due equal rights, everybody gets equal stuff underneath citizenship. Finally, we've said Black men, at least, can't be stopped from voting, not that they have to vote but you can't stop them. Those are the things.

Veralyn: Okay, to me, I'm just hearing all of these. It's like this thing happened but right away, a caveat. This thing happened but right away, a compromise. I can't help but think about the ways in which our very first episode, live, we were asking people, "What do you want from the Democratic Party?" A lot of the responses to that is like we want them to stop compromises. We want them to actually go after the things that will make our lives better, our lives different. At what point does the compromise negate the achievements? I'm happy not to be a slave, but-- [laughs]

Kai: Listen. This is the thing. There's no question. From the beginning of introducing these new ideas of how to be a truly multiracial society, it was shared opportunity. They began compromising with white supremacy around it and we still are today and that is frustrating.

Veralyn: To me, the most radical thing they did was write it down. [laughs]

Kai: That's also not true, Veralyn. The point is, there was a period in history where, in fact, these ideas were being executed upon. The problem is that we want to think of American history as though it's this linear thing and it's a linear progress or it's a linear failure. Yes, there was some people were fighting it, tooth and nail from jump. Maybe they will always be fighting it, but this was the moment where we said, "Okay, we want a racially just country," and there was a period-- It was short, but decades, maybe 20 years in the most expansive.

Veralyn: [unintelligible 00:41:05] .

Kai: Can we not erase what amazing things Black people were able to achieve in that time period? Because part of that project is to erase those achievements. We opened businesses, we started newspapers. We've talked about on the show about the way Black literacy shot up. Black schools opened up. There was all this Black achievement happening and that Black achievement came out of these reconstruction amendments as flawed as they were. We still were able to step into them and start doing things.

Eric: The problem is that it faces violent opposition in the South. It's not just normal political conflict, but these governments are met with the Ku Klux Klan and groups like that and the terrorism, really. Again, you can link that era to the present just via the problem of terrorism. The Ku Klux Klan clan was like our Bin Laden and Al-Qaeda using ultra-violence to try to gain political ends.

Kai: The purpose of the clan is, "Okay, we've lost the political fight. We have to have an armed rebellion to bring back these former Southern governments."

Eric: To bring back white supremacy in all realms. The plan is, number one, against Black voting, against Black office holding, but they're also targeting school teachers. They're targeting African Americans who get into contract disputes with their employer on a farm. They target white Republicans in the South, white Southerners who cooperate with these governments.

Yes, it's political in the first instance in terms of their aim is to paralyze these governments, but it's much broader than that too. It's about white supremacy per se, but going along with that, is also this retreat on the part of the North little by little that the will, the commitment to enforce the egalitarian principles of reconstruction wanes.

[music]

Kai: I've said this a few times on the show. Throughout the summer, as protests filled the streets and many people became so much more engaged, I kept hearing this question, "What will all this add up to? Will it work?

[music]

Reconstruction offers a clear lesson on what won't work. People get tired of the fight because the people who like things just the way they are, history suggests they will not get tired. Before we finish with Eric Foner, I want to turn to one last chapter in the reconstruction story. A really concrete impediment to racial justice.

Reporter 7: Tonight it appears Republican senators will have the votes to confirm a new Supreme Court justice before Election Day.

Mike Pence: The Supreme Court of the United States has never ruled on whether or not the language of the 14th amendment--

Kai: Let's talk lastly about the Supreme Court.

Eric: Yes.

Kai: In these amendments, Congress understood that they were going to be the protectors of these rights. That was the idea--

Eric: That's what it says. Each amendment has a thing. Congress shall have the power to enforce this amendment.

Kai: That is not how it played out.

Eric: On the one hand, Congress dropped the ball, but the fact is, yes, the Supreme Court [unintelligible 00:44:28] the power to delineate exactly what these terms meant, what these measures meant, who they applied to, how they were applied. Again, linking this era with the present, you see a graphic illustration of what can happen to your rights in the hands of a conservative Supreme Court. We now have an ultra-conservative Supreme Court in this country and the events of the 1870s, '80s, and '90s or the court decisions of those years should be a warning to us.

Kai: Remember, each of the three reconstruction amendments were pretty general principles written in ways that were fuzzy, or did it get the South support? The court had a lot of questions to answer about how to apply those principles in real life.

Eric: Little by little, it didn't all happen at once, but over a whole generation, every one of those questions, the court decided in the narrowest possible way. That is to say, they interpreted the amendments very, very narrowly what they applied to, who they applied to, what the grounds could be for congressional intervention. The result of that was a constant whittling away of the powers that the federal government thought they had put into the constitution to protect the basic rights of the former slaves. In fact, as the 14th Amendment is being whittled away when it comes to Blacks, it's being invigorated when it comes to the rights of corporations.

Kai: After all this work, trying to define freedom for Black people, which requires redefining everything about what it means to be an American citizen. After all of that, the Supreme Court uses these new constitutional ideas to give corporations more rights.

Eric: If you look at the whole period from 1870 to 1900, there may have been 120 cases before the court that in some way related to the 14th Amendment. Of those cases, only about a dozen actually dealt with the rights of Black people. The vast majority of 14th Amendment cases were the Supreme Court limiting the power of states to regulate corporations.

Now, they said, "No, states can't pass laws regulating railroad rates. That deprives corporations of their property without due process of law." There were laws passed limiting how many hours you can work in a mine in a day. "That's a violation of people's liberty. The state can't interfere with that." Any effort to regulate how these big corporations operated, was struck down by the Supreme Court under the 14th amendment. 10 times as many cases dealt with the rights of corporations has dealt with the rights of Black people.

Kai: At which, again, it really puts an incredible point on today's world, it feels like. You know what I mean? We had this moment where there was an opportunity to expand individual rights and instead of doing that, it expanded corporate rights, and here we are today. It feels like the world we live in.

Eric: Around 1891 or '92, Frederick Douglass in a speech said, "We are living at a time when principles that we thought had been firmly established are being challenged and overthrown. We're in a post-anti-slavery world," he says. In a way, we're like that too. Principles that one thought had been established are under challenge now. In a certain way, studying that period can then maybe help us understand our own era better and how vigilant one has to be about protecting our basic civil rights and civil liberties and political rights because if there's one lesson of this whole thing, rights can be gained and rights can be taken away and it has happened in our country.

[music]

Kai: Historian Eric Foner is the author of The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution. Huge takeaway for me is the impact on voting rights. We'll be talking about that next week when we report from Wisconsin, where we see up close the consequences of new affirmative right to vote in this country. If you enjoyed our conversation, I urge you to go hear some of our earlier stories on reconstructions. You can go to wnyc.org/anxiety or wherever you get your podcasts. I'm Kai Wright, this is The United States of Anxiety. Thanks for spending this time with us. Talk to you next week.

[music]

The United States of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios. Jared Paul makes the podcast version. Kevin Bristow and Matthew Marando were at the boards for the live show. Our team also includes Carolyn Adams, Emily Botein, Jenny Casas, Marianne McCune, Christopher Werth, and Veralyn Williams. Our theme music was written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band. Karen Frillmann is our executive producer and I am Kai Wright. You can keep in touch with me on Twitter @kai_wright. That's K-A-I and Wright, like the brothers. If you can, I hope you'll join us for the live show next Sunday, 6:00 PM Eastern if you're streaming on wnyc.org or just tell your smart speaker to play WNYC. Until then, thanks for listening. Take care of yourselves.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.