Hernan Diaz’s “Trust,” a Novel of High Finance

David: The daughter of eccentric aristocrats marries a Wall Street tycoon during the Roaring Twenties. It all sounds like a book that F. Scott Fitzgerald might have written, or maybe Edith Wharton, something in the vicinity of The Great Gatsby or The House of Mirth but Trust by Hernan Diaz is very much of our time. It's a novel told by four different narrators who give conflicting accounts of the marital life of a fictional couple, and also of the tycoon's gross misdeeds and his role in the crash of 1929.

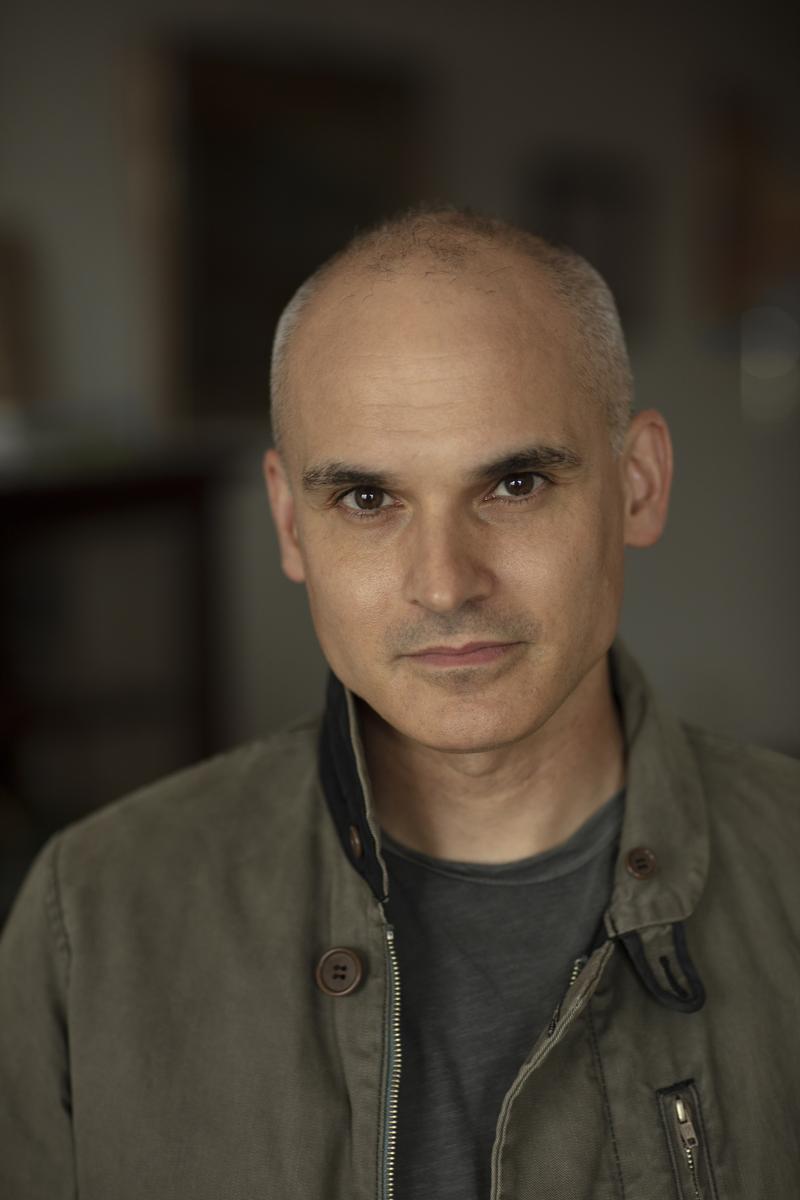

While a book like Gatsby or The House of Mirth tends to skirt around the question of how the rich actually make their money, Hernan Diaz puts that question at the very heart of Trust. He's concerned with finance capitalism, and how it works, and what's ignored along the way. The book received a Pulitzer Prize this year, and I asked Hernan Diaz about the title Trust.

Hernan: I wanted something that was performing what the book was also doing and saying. Trust has the value of having sort of all these semantic strata. It's a highly layered word, and it addresses the financial aspect of the novel, but also what to me above the issue of capital in the novel, it speaks to the issue of confidence. The novel Trust is a gentle invitation to the reader to question these tacit agreements that we all enter into every time we read a text. This is why we have four voices.

David: As I mentioned, Trust isn't one linear story. It's told in four parts. One part is a work of fiction, a book within a book, and there are memoirs in a personal diary by other characters. Each part reveals more and more about the mysterious financier Andrew Bevel and his financial dealings.

Hernan: What I was interested in in the book, and this is also why I chose finance capital over the manufacturing of concrete goods or providing tangible services. I wanted a realm of pure, absolute abstraction. In the book at one point, someone speaks of the incestuous genealogies of capital. Capital begetting capital begetting capital. This removal, I think, that leads eventually to labor, of course, but in that dizzyingly high spheres of finance, every human trace of labor has been erased. I was very interested in that.

Also that high degree of abstraction allowed me to think of these financiers in my book a little bit. I don't mean this as a redeeming quality at all, but a little bit as esthetes or pure artists who are all about the process and not about the result.

David: That's fascinating, because in the first section, I get that entirely, that his engagement with money is as the luxury part of it. The reward doesn't seem to mean anything to him. It's the game itself.

Hernan: Absolutely. That's what I was going for, just to show money purely as an abstraction and not as a means to an end.

Speaker 1: If asked, Benjamin would probably have found it hard to explain what drew him to the world of finance. It was the complexity of it, yes, but also the fact that he viewed capital as an antiseptically living thing. It moves, eats, grows, breeds, falls ill, and may die, but it is clean. This became clearer to him in time. The larger the operation, the further removed he was from its concrete details. There was no need for him to touch a single banknote or engage with the things and people his transaction affected. All he had to do was think, speak, and perhaps write.

Hernan: The core of the book takes place in the late '30s, so I thought I would read everything that would have been accessible up to that point. I went from Benjamin Franklin to Herbert Hoover. That was the time span. I read everything I could find over those couple of centuries.

David: You're reading about the robber barons. You're reading about the major industrialists, financiers, and bankers.

Hernan: I'm reading them as much as I can.

David: I also know that you come from a background. Your parents were committed leftists, I think is the phrase in The New York Times Book Review. That's the short answer.

Hernan: Really?

David: Trotsky esteem. How much of those politics did you inherit and make your own and bring to the book?

Hernan: None is the answer. My father, I'm reluctant to say this publicly, but my father's ghost haunts a great part of this book. There is a character who is an Italian anarchist who's very dogmatic, very unbending, inflexible, and it was a ciphered way for me to deal with that legacy from my father, whom I loved very much. He died some seven, eight years ago. He also moved away from that political paradigm.

David: This is the character of [unintelligible 00:05:50]?

Hernan: That's right.

David: You have four voices in this novel. The reader, and people listening should know that it's not like The Great Gatsby. It's not in just the voice of Tom. You shift point of view, you shift time and place. It's extraordinarily clever but the cleverness should not be an anti-endorsement. It's part of the immense appeal of the book. How is that architecture built and toward what end?

Hernan: I was hoping it wouldn't be a gimmick or a mere--

David: If it had been, I would have thrown it against the wall and moved on to the next thing.

Hernan: I probably would have given up myself, too, as a writer, because I'm not interested, in--

David: Deep part of the pleasure of the book.

Hernan: Oh, thank you. As I was saying before, I thought that the best way and the most fun way for the readers, hopefully, to try to interrogate the ways in which we read would be for me to confront them with different texts, in different voices, in different genres, written in different periods of time, and build a certain trust, forgive me, for each one of these four voices and then swiftly proceed to demolish it and then rebuild it for the next section that also interrogates the preceding one.

In other words, instead of merely presenting the issue of voice in a monographical way within the novel, why not enact it formally, and have it be an experience in reading the text.

David: Of these main characters, did you find them all equally enjoyable to write about or is enjoyment just not a factor in the hard work of writing?

Hernan: Enjoyment is a big factor for me. I don't buy into the whole Dostoevsky notion that one should be in some kind of--

David: You're not sweating blood at the desk.

Hernan: I'm not. I mean, life is too short. There are other things to do. If you don't enjoy writing, what's the point?

David: I read somewhere that the two writers that interested you in driving that forward were Lillian Ross, a writer for The New Yorker.

Hernan: That's right.

David: Who invented the celebrity profile with her profile of Hemingway many, many years ago, and Joan Didion, quite a different writer, whose sentences fall on the page like one razor blade after another. Quite a very different voice.

Hernan: Yes, Didion was a massive presence there, and I realized, here's a little anecdote, all voices had to be very different, and I didn't want to bribe the reader with little tchotchkes and mannerisms, that's the easy way to do it. I didn't want to resort to different fonts or any design distinction between-- It had to be, in a subtle way, in language. My heart sank when I realized, editing the third version, that the use of commas in certain subordinate clauses was the same for everyone. I reread Didion's White Album, which is my favorite book of hers, marked up all of the commas in it, and then proceeded to steal it.

David: [laughs]

Hernan: And it was such a disaster, David. It sucked so hard. It didn't work at all, but that failed experiment that consumed so much of my time learned me to punctuate and to use commas, famously the hardest punctuation mark there is in a totally new way.

David: Hernan, I've got to confess, I didn't know your books, and I didn't know your name before reading Trust anyway. You've just turned 50 and I hope you'll forgive the impolite question. Were you a late starter to fiction? Can you tell me your story of getting started as a writer of novels and stories?

Hernan: I always knew I wanted to be a writer. Even before I learned how to write, I would show my mother doodles as my latest story. I've always been doing things around books. I'm an academic. I worked as a critic, and of course, writing fiction all along, for the most part in English. For the longest time, well over a decade, I wasn't able to place my work. It was turned down by magazines, by collections, short story collections. I had novels that I couldn't place either, turned down by editors and agents.

David: Including this magazine, I gather.

Hernan: Including this magazine.

David: Okay, our loss, these things happen.

Hernan: Yes, with perfect consistency.

David: [laughs] For how long? When did you start writing fiction and submitting them to editors?

Hernan: I would say in the early 2000s. This is all I wanted to do, despite the world telling me to please stop. I was doing it in a void, without any kind of objective legitimation from the world. In the Distance is my first published novel, but there's a whole invisible body of work, including novels that I probably won't publish now because I'm a different writer. I wouldn't say I'm a late bloomer, I just was very late to be published.

David: Was the world too hard on you? In other words, was the world wrong?

Hernan: I don't want to take out my tiny little violin here and say how the world wronged me in any way. What I will say is, I am the same writer now that I was then. Of course, there has been growth, evolution, transformations, metamorphoses, but I'm not going to lie, there is a sense of vindication because I've been consistent. I didn't change the course is what I'm trying to say.

David: You were born in Argentina, spent time in Sweden, and back to Argentina, and it wasn't until you were a grown man that you moved to the English-speaking realm. Tell me about your history of your language and how it works. In other words, I assume Spanish is your first language. How quickly were you fluent in English?

Hernan: I don't know. Spanish is my mother tongue, it's what we spoke at home, always still. Then we moved to Sweden and Swedish became my social tongue and then we moved back to Argentina, and I feel that Swedish was taken away from me. We didn't speak it at home anymore.

David: Did you lose it?

Hernan: No, I speak it without a trace of an accent but with the vocabulary of a 10-year-old. Most exchanges with strangers begin with, I have to explain this to you, so they know.

David: Then how does English enter your life?

Hernan: Right. In my early teens, I think I must have been 14, 15, English came to me through Borges, who was a very important writer to me, and a big Anglophile. He introduced me to the Anglo-American canon. I started reading Stevenson, Whitman, Hawthorne, Emerson, and so on and so forth, thanks to him.

David: Why did you make the decision to write Trust in English, your fiction in English?

Hernan: I wrote Trust in English, In the Distance, all my stories, and all those unpublished texts. Aside from the big events in my family and having a family, becoming a parent, and meeting my wife, I think English was the biggest event that happened to me in my life, that encounter, to the extent that I shaped my life around it. I moved to England, then to the United States to live in English. Now, it's very hard to explain love, and that's what I feel for the English language. I can rationalize it. I can give you a little listicle, if you want, of reasons why it speaks to me and why I speak through it.

I love its lexical wealth and generosity, its inclusiveness. Roman's languages expel words from their dictionaries and-- [crosstalk] They're very conservative. Spanish is conservative. I think French is as well, Italian might be as well. Yes, you have the academia, the Royal Academy in Spanish.

David: Isn't Spanish full of inclusiveness, geography, slang, and all kinds of flexibility the way English is?

Hernan: Oh, absolutely. No, I'm just talking institutionally. I want to make this abundantly clear, I am most emphatically not saying that one language is richer than the other. I was just merely talking about the academy and institutional policy regarding language, and I feel English is, without a question, as a language, more inclusive than other languages.

David: Hernan, the thing that you care about so intensely, the creation of these texts and the reading of these texts, I'm holding your book up, it means everything to you, and yet it too exists in an economy. It exists in what we now call, endlessly, the attention economy that competes against-- I'm now picking up my phone, and all the other million things that it competes against. A lot of literary writers are concerned with, and you hear this complaint all the time, that this is becoming, and it always was a minority obsession, but it's now becoming even more so.

Even as it becomes a richer, more diverse world of voices being published, the business of setting aside two hours in an evening of concentrated attention on an enigmatic text gets harder and harder.

Hernan: I know, and it breaks my heart because precisely what I like about the novel as a forum, another thing that I like, is that it enables us to experience time in a totally different way. The way it compresses and dilates time, the time within the text and the time passing for us as readers, and how those two are in conversation or tension, is a beautiful thing to me. I understand it's antagonistic to the way we live now but perhaps we should put this in historical perspective. Universal literacy is a very new thing, historically speaking.

It's hardly, I don't have the years here, but wouldn't you say it's around a century long in the West, which is the place that I know a little bit of. Before then, the written words circulated in a very limited way, and of course, that was a power move that goes without saying. I think this period, where literature reigned in this way and was our main way of interacting with meaning, might be at an end. This doesn't make me happy at all. I'm just taking a step back and looking at--

David: I think it might be at an end.

Hernan: You do.

David: I'm asking you.

Hernan: It's definitely changing our experience with text, how we navigate text. Words, written words, has changed already. Add to that the fact that we are increasingly communicating in nonverbal ways, and very effectively so. I don't want to be conservative or an old curmudgeon. I think it will be very interesting, and it will be exciting, but it probably won't be for me.

[laughter]

David: Hernan Diaz, thank you so much.

Hernan: Thank you, David. This has been such a joy.

David: Trust is the second novel by Hernan Diaz, and it won the Pulitzer Prize this year.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.