BROOKE GLADSTONE: We end with an appraisal of a free-speech crusader who’s not famous for suffering or sacrifice.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

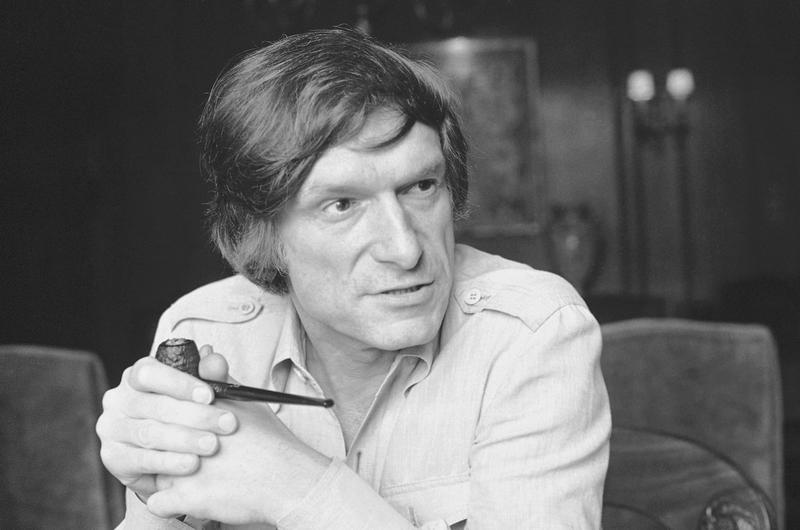

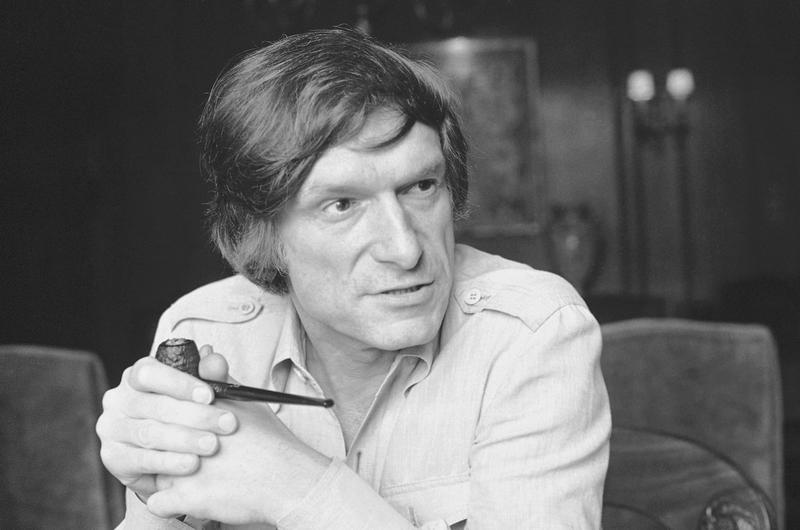

I speak, of course, of Hugh Hefner, who died Wednesday at the age of 91, his ashes interred in a Los Angeles cemetery in the crypt next to Marilyn Monroe’s, just as he planned. Marilyn was his first cover girl in 1963. Though already a year in her crypt, she made Playboy. That Hefner made bank off of women's breasts is self-evident but did he give back? I spoke to him in 2003.

[2003 OTM CLIP]:

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You know it's an amazing thing you did, weaving together a passion for literature, civil rights, runny cheeses and big breasts into what you call "a viable aesthetic."

HUGH HEFNER: And it was an attempt to incorporate in a positive way a sexuality into the rest of the kinds of interests that a person spends their time on when they're not working. Our notion of playing hard was largely bowling and watching television, and there was more to life than that. I think that, you know, our traditional values, and, and our -- they're rooted in our religious values -- has pitted mind and body against one another, the notion that the devil is in the flesh. I didn't buy it when I was young. I don't buy it now.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In the Playboy philosophy, you quote from one of your most eloquent critics, Harvey Cox, who wrote a piece that was reprinted in various Christian journals of opinion and college newspapers. Can I read you his quote?

HUGH HEFNER: Sure. Of course.

BROOKE GLADSTONE/READING: "Moralistic criticisms of Playboy fail because its anti-moralism is one of the few places in which Playboy is right. Thus, any theological critique of Playboy that focuses on its lewdness will misfire completely. Playboy and its less successful imitators are not sex magazines, at all. They dilute and dissipate authentic sexuality by reducing it to an accessory, by keeping it at a safe distance." And he concludes with, "We must see in Playboy the latest and slickest episode in man's continuing refusal to be fully human."

HUGH HEFNER: Well, I think that's very sophisticated semantics but not very accurate. I mean, the reality is that, far from being accessories, the romantic relationship between the sexes, expressed from a male point of view, is what Playboy is all about. It's what makes the world go around. The fine food and wine and the clothes and the cars and the gadgetry, those are the accessories, but the part that really matters is the connection between the opposite sex.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Here's a clip that we borrowed from your A&E Biography. It's you being challenged by feminist Susan Brownmiller on The Dick Cavett Show.

[CLIP]:

SUSAN BROWNMILLER: The role that you have selected for women is degrading to women because you choose to see women as sex objects.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

You make them look like animals, yes. Women aren’t bunnies, they’re not rabbits, they’re human beings. The day that you are willing to come out here with a cottontail attached to your rear end…

[SOME AUDIENCE LAUGHTER]

HUGH HEFNER: We've been accused, obviously, of exploiting women, exploiting sex. I think Playboy exploits sex -- you know, I just think "exploit" is an unfortunate word. Playboy exploits sex like Sports Illustrated exploits sports.

[END CLIP]

[HEFNER LAUGHS]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, I noticed that you never responded to [LAUGHS] her specific challenge about the bunny tails. I mean, it would, after all, be antithetical to the Playboy aesthetic to attach a little fuzzy ball of cotton to your own tush, wouldn't it?

HUGH HEFNER: Yes, I think so. [LAUGHING]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] But is that fair?

HUGH HEFNER: And that feminist diatribe, it didn't make a lot of sense back then. It seems very foolish today. I think that in the intervening years, women really have become truly human. That anti-sexual part of feminism is very antiquated and, quite frankly, was anti-revolutionary even at the time. To be truly h -- human, women have to embrace their sexuality.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Back in the early days when you were creating that costume and that image, it wasn't women expressing their own sexuality. It was women putting on the costume that you had designed for them.

HUGH HEFNER: Yes.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This was -- this wasn't them embracing their own sexuality, this was them embracing yours.

HUGH HEFNER: True. That's what makes it work.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Can you say anything about how the image of the Playboy bunny has evolved? I mean, does she still find walks on the beach a turn-on and mean people a turn-off?

HUGH HEFNER: Probably. [LAUGHS] It’s just some th - some things in terms of humankind don't change that much.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What are you wearing?

HUGH HEFNER: Pajamas, of course. [LAUGHS]

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It seemed to me that he regarded playmates as delectable dimwits. As for the rest of womankind, I don’t know. I don’t much care. While he may have been an aspirational icon in his mid-century prime, I was a little kid in the ‘60s and to me he seemed weird, like an overgrown adolescent in a velvet smoking jacket?

But adolescents can do amazing things with sex and money, maybe even blaze new paths in a prudish nation’s freedom of speech.

Writer Gay Talese, a notable practitioner of new journalism, certainly thought so. Fifteen years ago, he spoke to Bob.

[2003 OTM CLIP]:

GAY TALESE: Hefner in, in the 1950s, introduced into Middle America a sense that women with their clothes off belonged in our lives and they were okay, and that was the big thing, in the beginning, at least, of Playboy's contribution to popular culture. What it did was bring to the jury system a diminution of being shocked by nudity because they'd seen so much of it. All that nudity that Playboy extended into small towns and, and, and restricted areas and into home life, it gave a kind of a, a sense of being blasé toward the nude female form, so that when they, in pornography cases, voted whether to or whether not to punish a person who was brought up on charges of obscenity, they tended to acquit, rather than convict.

BOB GARFIELD: But did the legal decisions that resulted from the anti-smut prosecutions by the postal inspectors and other agencies, did they extend beyond the issue of pornography into other areas of free speech?

GAY TALESE: They most certainly did. The dirty work was done by the pornographer. It wasn't done by Alfred A. Knopf or Random House or, or the Library Association of America. They did nothing, in terms of free speech. It's because the smut peddlers took the beating in the courts. They fought the government. They fought the Catholic Legion of Decency. They fought the moral code. And they made it open for Arthur Miller, Philip Roth, John Updike, Joyce Carol Oates. They all owe to the smut peddler their freedom.

Hefner is a major figure in fighting against repression, and that means any kind of repression. It isn't just the right to show naked women or naked men, or whatever. That's part of it. But if you can show naked women and naked men, you can show a lot of nakedness, in terms of language. You don't have to worry about putting a fig leaf on a verb, don't you see?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Bob asked Talese about all those great interviews and all the great writers that graced the pages of Playboy in its heyday. Were these first-rate contributions to Playboy ever anything more than window dressing for soft porn?

GAY TALESE: Obscenity, in order to be not obscene, has to have redeeming social value. So Playboy had, in addition to the naked women we all might have lusted for, redeeming social value in the form of a lot of boring interviews with, with Noam

Chomsky --

[BOB LAUGHS]

-- that was there in the pages of Playboy. There were good writers, Irwin Shaw in the old days, and Norman Mailer and John Updike, I mentioned again, and Joyce Carol Oates. But you take those girls and you banish them to Siberia and Mr. Hefner, and Playboy with him, goes into receivership. He, he's out of business. He's back in Chicago without a swimming pool, without a Jacuzzi, with nothing. [BOB LAUGHS]

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

Let me tell you where I stand with Playboy. I don't read it. I never read it. I never have published a piece in it. I've never submitted an article to be published in Playboy. Okay? My defense of Playboy is because Playboy made my life and the life of every writer easier.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So when America's foremost self-gratifier left the building, at least he left a gratuity. Hugh Marston Hefner, born in Prohibition Chicago, deceased in Trump's “grab ‘em by the hoo-ha” America, Hef, who famously said, “In my wildest dreams, I never could have imaged a sweeter life.”

BOB GARFIELD: That’s it for this week’s show. On the Media is produced by Alana Casanova—Burgess, Jesse Brenneman, Micah Loewinger and Leah Feder. We had more help from Jon Hanrahan and Monique Laborde. And our show was edited -- by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Sam Bair and Andrew Dunn.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schachter is WNYC’s vice president for news. Bassist composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield.

* [FUNDING CREDITS] *