Gun Violence is a Public Health Crisis

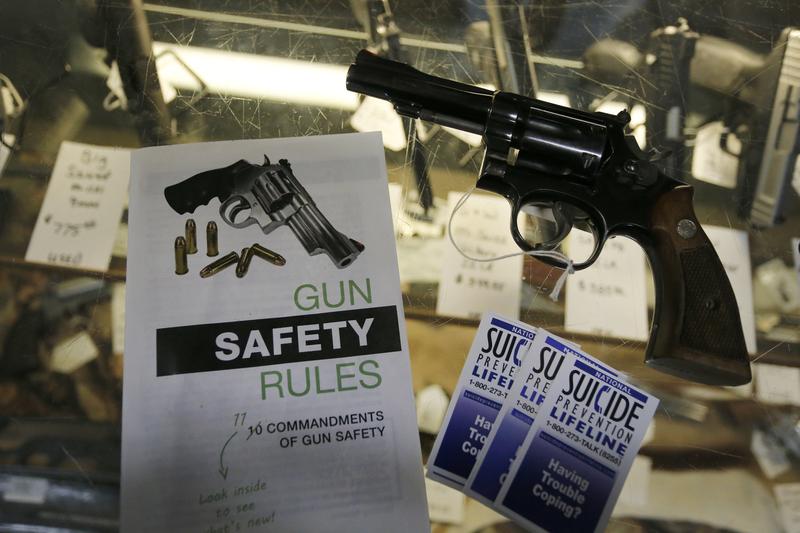

( AP Photo )

[music]

Speaker: I'm angry and I want to know why this keeps happening.

Speaker: I am despondent.

Speaker: I'm feeling sick, I'm feeling outraged, I'm feeling upset, feeling like we all need to do something

Speaker: I'm pissed off.

Speaker: I'm sick of it. Shame on America.

Speaker: Absolutely livid.

Speaker: I'm very conflicted.

Speaker: I feel hopeless that this is never going to change.

[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: This is The Takeaway. I'm Melissa Harris-Perry. Yesterday, we asked you to share with us how you're feeling in the aftermath of two devastating gun violence massacres. Now, we're going to have more of your responses later in this show, but the reality is this tragedy is affecting so many of us in ways big and small. I know in my household yesterday, when we sent our second grader off to school, she was fine. My husband and I were not. Like so many parents across the country, we knew what we did not want to say out loud, that it could have been our child.

There was a tweet from a parent, Travis Cravey who said his 11-year-old saw him crying and asked if it was about Uvalde. Travis said, "Yes, it's really sad, and I worry about y'all." His son responded, "It's okay, dad, we train for this." Those trainings, they're too much for some teachers. There's one who tweeted, "I had to inform my students that we will probably have an active shooter drill." Five of them cried, two of them said they would want to fight the gunman, and three said they don't want to come to school if it's going to get shot at. Talking to kids about this is hard.

Angel Garza: Every morning he wakes up, he asks for his sister.

Melissa Harris-Perry: That's Angel Garza talking to CBS's, Tony Dokoupil. He lost his 10-year-old stepdaughter, Anne Marie in the shooting. He and her mom aren't sure what to tell their three-year-old Zane.

Angel Garza: I just want my baby home. I don't care, I don't care about anything else. I don't care about nothing at all.

Melissa Harris-Perry: This grief is what President Biden described during his address on Tuesday night.

President Biden: There's a hole that's in your chest, you feel like you're being sucked into it and never going to be able to get out. It's suffocating. It's never quite the same.

Melissa Harris-Perry: The suffocating hollowness extends far beyond immediate families, beyond the boundaries of Uvalde. It's a monstrous helplessness many of us feel.

Speaker: I feel hopeless that this is never going to change.

Melissa Harris-Perry: In 2016, the American Medical Association declared that gun violence in the US is a public health crisis. Not just the mass shootings, which make national headlines, but the daily violence that constitutes the overwhelming majority of gun injuries and death, suicide, intimate partner violence, murder, police killings, and even accidental shootings. It is the grand insight of English poet, John Donne's 17th-century poem, any man's death diminishes me because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee. I'm joined now by Dr. Megan Ranney, she's an emergency physician and academic Dean at Brown University's School of Public Health. Thanks for joining The Takeaway, Dr. Ranney.

Megan Ranney: Thank you for having me on today

Melissa Harris-Perry: Because it's a time when we need to be checking in with one another. I know you have children in school. How are you, and how are they?

Megan Ranney: I have a fourth-grader. I looked at those pictures of those kids and could only think there, but for the grace of God, goes mine, but my kids are doing okay. They've come to accept this as part of life. They've shrugged it off and went to school yesterday with no more care than normal fourth and seventh-grader would have.

Melissa Harris-Perry: From a perspective of sort of broader public health for those of us who maybe can't shake it off or are going to take a lot longer to shake it off, as adults who may be a little bit less resilient, what are the effects that it has on us and on our potential health?

Megan Ranney: This constant exposure to trauma, whether you're in the community itself or whether you're watching it on the news has very real mental and physical effects on us. It causes anxiety, it can cause nightmares, over time it can cause post-traumatic stress. We have studies showing that folks who are exposed to terrorism, to mass shootings, develop physical symptoms as well, headaches and stress-sensitive diseases, things ranging from autoimmune disorders to heart disease.

In fact, there's one heart attack that's caused by severe stress, a broken heart syndrome, or takotsubo where your emotional response is so strong that it almost stuns your heart muscles.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Help folks to understand what it means to say you study gun violence from a public health standpoint.

Megan Ranney: Studying gun violence and firearm injury from a public health standpoint is about these secondary effects of exposure to firearm injury. It's also about the long trajectory that gets us to this point. We need to talk about the individuals, about that individual kid who got shot, and about the individual who picked up the gun. We also have to talk on a population or societal level about what got us here and how to heal and move forward.

Melissa Harris-Perry: I feel like we began to have a public health conversation in the context of the pandemic, and then it didn't go so well that public health conversation that we were having that sense of, when you mask, you may not be masking exclusively for your own health and wellbeing, but for the health and wellbeing of the people in your household, or the person at the grocery store or the first responder or whomever, the public, is there a way to have a better, more productive public health conversation around gun violence?

Megan Ranney: I think there is. As sad as it sounds, I actually developed a bunch of the skills and techniques that I used during COVID working on firearm injury. It's about creating community, about working with trusted messengers, about creating solutions that may not completely eliminate harm, but reduce it, and about moving forward in ways that allow folks to step into that void of hopelessness and fear.

I think we did have many successes during COVID. We here in the United States developed vaccines in record time. Although there were certainly failures, although we have lost far too many lives, since vaccines became available, we did get them out the door and into many arms. I also think we learned a lot of lessons about the power of disinformation and misinformation during COVID. We see those same lessons repeat themselves around firearms. Already there are disgusting and wrong stories being spread about this shooting in Texas.

I think it's on us from a public health standpoint to think about how to stop those, how to combat them, and how to inoculate ourselves with real strategies that we can use to help ourselves in our communities.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Say a bit more about that capacity to counter misinformation.

Megan Ranney: The first thing is knowing that it's out there, knowing that it exists, that there are people who literally make money off of creating and spreading lies. The second thing is that there's also an absence of information, and when there's a void, those fake stories are more likely to spread. One of the things that I spend a lot of time working on around firearm injury, is around trying to educate and to change social norms. Simple things like, did you know that most shootings in this country are actually suicides, not homicides?

Now, these mass shootings are never events, they're terrorism, they're horrible, and I can talk about all the reasons why they happen, but knowing the facts about firearm injury is a first step to preventing the spread of these types of horrible misinformation about what causes firearm injury. Then it helps to prevent us from going down the road of fake solutions or things that will actually harm us. That's just one small example of how this can work.

Melissa Harris-Perry: You've been doing research around firearm injury in terms of direct exposure to gun violence on children, as well as this broader social exposure. What do we know? I mean, obviously, if a child experiences a gunshot wound, a non-fatal one, then we expect there to be physical effects, but what else do we know about that direct exposure to gun violence on children?

Megan Ranney: The caveat I'm going to give is that most of the research that I and others have done has been done largely on our own dime. It wasn't until two years ago that Congress finally re-appropriated a small amount of money to the CDC and NIH to formally study firearm injury prevention and the consequences of exposure to firearm injury.

Melissa Harris-Perry: With that, pause. That caveat is too important to go past quickly. I promise I want to hear about the research. What are you saying to me? In 2020, the data are showing us-- I just saw this piece in the New England Journal of Medicine. The data is showing in 2020 that for young people, gunshot wounds became the leading cause of death for young people overtaking car accidents, probably because the pandemic so significantly reduced how much driving was happening as well as increasing gun violence at the same time.

What in the world do you mean that we were not studying the leading or second cause of death for our young people?

Megan Ranney: Isn't that almost incomprehensible?

Melissa Harris-Perry: Since 1996, there was this thing called the Dickey Amendment. A junior representative from Arkansas, J. Dickey passed an amendment that said that the CDC could not use funds to promote or advocate for gun control. Now, the CDC doesn't advocate for anything they're not allowed to. It was a pointless amendment but at the time that that was passed, Congress removed from the CDC all the money that they had been spending to research firearm injury prevention. Again, create evidence on how to prevent it, and how to prevent its aftermath.

Then a couple of years later, money was removed from NIH, as well. In 2018 and 2019, many of us in healthcare started to raise the alarm. I shouldn't. We've been doing it for a while, but it got louder in 2018 and 2019 after Parkland. In 2020, for the first time in 23 years, money was finally appropriated. I should say that it's a drop in the bucket. Many of the strategies that we use to talk about firearm injury prevention, much of the data that I quote was created with foundation money or again, on researchers' own time. Much of our work is really stuck in the same theories that we had in the 1990s, which is ridiculous. We wouldn't accept that for cancer or heart disease, and we shouldn't accept it for something that is the leading cause of death in kids.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Let's take a quick break. We're going to have more with Dr. Ranney on public health when we come back, it's The Takeaway.

[music]

Still with me is Dr. Megan Ranney, an emergency physician and academic dean at Brown University's School of Public Health. Okay, in a certain way, I have to say, Dr. Ranney, I'm a bit surprised that as an emergency room physician you're doing work on public health. I say that only because it feels like our narrative about ER physicians is the very immediate, not the long-term chronic, and very much the individual patient, not the broader collective. Talk to me about how you ended up thinking about gun violence in this much more public health framework?

Megan Ranney: I'll start by saying I actually chose emergency medicine both because of the acute care and because we really are the safety net for society. We are the canary in the coal mine for everything that goes wrong with our healthcare system and with the larger world in which we live. It thereby offers us a chance to offer help to those who may not have other options. Unfortunately, that includes victims of firearm injury. I like any other ER doc, or nurse, or respiratory therapist, have taken care of countless victims of gunshots in the ER over my career.

The first one was when I was a med student and they've continued. There are a few who stand out and who changed the way that I think about firearm injury. About 15 years ago, I took care of a young man who shot himself with his father's firearm and that shifted my entire approach to this problem. It moved me from thinking about this as something that I have to treat, where I just save your life and send you up to the trauma surgeons, to something where I think about the question of what was the sequence of events that got the person into my ER in the first place?

There's an old story that many of us in public health tell around a bunch of villagers taking care of people at the bottom of a waterfall who are drowning. Day after day, the villagers see that there are folks trying to paddle for their lives in this river, and they pull them out and save them, resuscitate them, and send them on their way. One day, one of the villagers looks and says, "Why are all these people ending up in the river next to our village?" They go upstream to the top of the waterfall and find the folks are going over the waterfall because there's no signs telling them not to.

The villagers put up a net and a couple of signs, and lo and behold, they no longer have to save drowning people next to their village. That story is one that has stuck with me, and that motivates this work because I can do my best to save a person's life in the ER, but often it's too late. The non-physical consequences are things that are so difficult to heal. Instead, I choose to go upstream, which is the essence of public health. I choose to say what are the structural and personal drivers that got someone to that point of either picking up the gun themselves, or being shot by someone else, and how do I change them? There's no single solution.

I do think that's important to say as we struggle in this moment, there is no one thing that we are going to do that is going to fix this. Just as honestly there was no one thing for COVID vaccines, but also masks, doing searches, right? That shouldn't stop us from doing one thing, and then another thing, and then another thing, because in combination, there is plenty of evidence out there that we can make a dent.

Melissa Harris-Perry: We have seen this nationwide rise in suicide among young people. Talk to me about ER experiences in that context, both in terms of the lethality of suicide attempts, but also simply for adolescents who are in a mental health crisis and find themselves in the ER. What does that mean for what's happening in emergency rooms?

Megan Ranney: Let me be very clear that we have been experiencing a mental health crisis among adolescents as well as adults for a long time. This pre-dated COVID. It certainly worsened during COVID with folks' isolation and with anxiety and grief and hopelessness that we all experienced. It cannot be blamed on COVID. It certainly cannot be blamed on masks. It has worsened over the last two years, not just because we're all experiencing more anxiety, but also honestly because we don't have enough staff.

The healthcare system and I've talked to you about this before, has been affected by mass resignations. We've seen about 20% of folks who work in health care leave in the wake of COVID. That has affected ERs, but it's also affected mental health care. There are fewer psychiatric beds than ever before, there are fewer therapists than ever before. What that means is that kids are not getting care until they're in a moment of crisis.

The ER is the only place for them to go, we have inadequate resources to link folks to as an outpatient, and we have inadequate inpatient beds to admit children to. Kids then sit in the ER for days or weeks in what we call boarding. This psychiatric boarding crisis is horrific. It is the worst possible thing for someone in a mental health crisis, and it hurts our ability to take care of other patients coming through the door because there are no beds to see them in.

Melissa Harris-Perry: You said for weeks in the ER?

Megan Ranney: Yes, I have, not in my own hospital, but have colleagues across the country who have had children and adults who have spent literally weeks in the emergency department waiting for an inpatient psychiatric bed.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Is this because there are fewer beds because of the rise in the crisis, or are there fewer beds overall in residential treatment facilities for young people?

Megan Ranney: There are fewer beds overall in residential treatment facilities. That's a pattern that, again, pre-dated the pandemic. We saw a major decrease in the number of both pediatric, psychiatric inpatient beds, and adult beds in the decade prior to COVID. It's also of course that we have seen a rise in the number of people needing acute psychiatric care over the last two years. Again, largely driven by the fact that it's really tough to access outpatient mental healthcare before you get to that crisis point.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Are there solutions, even if there are expensive ones?

Megan Ranney: Just as there are solutions for firearm injury, there are solutions for our pediatric mental health crisis as well. The first is we need more therapists. Then there's a slightly earlier solution, which is creating community support, doing all those things that we know enhance kids' mental health and well-being, and enhance their parents' mental health and well-being because we know that the two are deeply inextricably linked.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Dr. Megan Ranney is an emergency physician and academic Dean at Brown University's school of public health. Thank you for being here, Dr. Ranney.

Megan Ranney: Thank you.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.