Georgia at the Intersections: Warnock vs. Walker

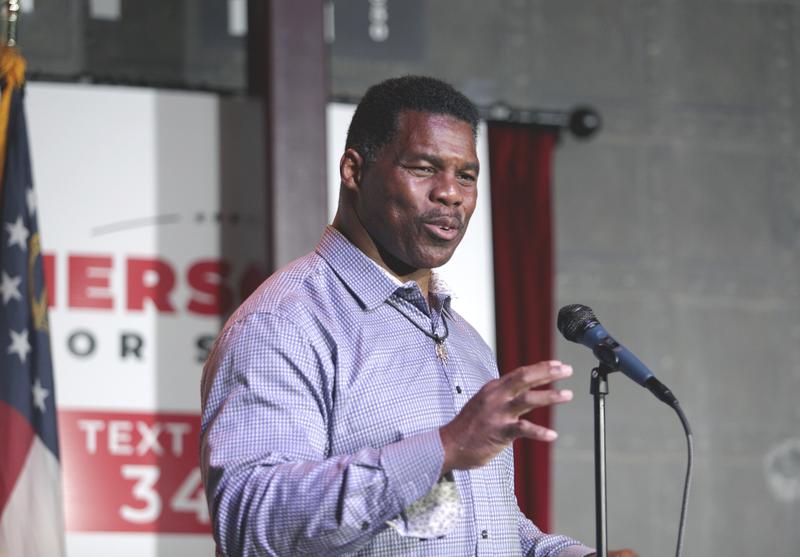

( AP Photo/Akili-Casundria Ramsess / AP Photo )

[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: Welcome to The Takeaway. I'm Melissa Harris-Perry. The 2022 midterms are a little more than 100 days away. On the ballot, 36 gubernatorial races, 36 Senate seats up for grabs, and all 435 House seats in play. One thing's for sure this November, just like in 2020, Georgia will be at the intersection of Americans' former and new political contours. In January of 2021, Rev. Raphael Warnock became the first Black person elected to the US Senate from Georgia.

Raphael Warnock: We were told that we couldn't win this election but tonight, we prove that with hope, hard work, and the people by our side, anything is possible.

Melissa Harris-Perry: One of the Republican Kelly Loeffler, who was appointed in 2019 following the retirement of the incumbent, which means that rather than serving a full six-year term, Warnock is back on the ballot and this is a critical race Democrats hope to create a working Senate Majority. One of Republican challenger Herschel Walker is a political newcomer, but a household name for Georgians.

Speaker 3: It's now a great pleasure to announce the winner of the 1982 Heisman Memorial Trophy from the University of Georgia, Herschel Walker.

[applause]

Melissa Harris-Perry: The former football star is a favorite of former President Donald Trump, who endorsed him in Georgia's Republican primary, which Walker won handily in May. This week at a campaign stop in Athens, Walker made his case.

Herschel Walker: See, I'm running for office because I'm tired of these gas prices being $5. I'm running for office because I'm tired of this inflation.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Walker's campaign has gained national attention less for his public policy positions, and more because of the attention to a string of missteps and gaffes. In addition, his ex-wife has accused Walker of domestic violence, and Walker has made apparently false statements about graduating from college, which the Atlanta Journal-Constitution found he never did.

Herschel Walker: People said Herschel played football but [unintelligible 00:02:15] I also was valedictorian of my class. I also was in a top 1% of my graduating class in college.

Melissa Harris-Perry: He's also making other false statements about having a lifelong career in law enforcement and disproving claims about his business interests.

Herschel Walker: [unintelligible 00:02:29] I own a food company [unintelligible 00:02:30] I own a large minority-owned food company in United States.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Also not so true. Last month, a Quinnipiac poll showed Warnock carrying a 10-point lead over his challenger, but more recent polling shows Walker and Warnock neck and neck. Now, Warnock seems to be leading among women in independence. Walker, on the other hand, among men and voters over 50. What exactly is Herschel Walker's appeal, and how much is at stake in this race? With me now is Maya King, New York Times politics reporter covering the South. Maya, as always, thanks for joining The Takeaway.

Maya King: Hi, thank you for having me.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Also with us is Andra Gillespie, political scientist at Emory University. Professor Gillespie, thanks for joining us as well.

Andra Gillespie: Thank you for having me.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Maya, let's just talk about how Herschel Walker ends up as the Republican nominee for the US Senate seat out in Georgia. How did he get into politics?

Maya King: Well, quite easily if you're talking about how he was able to go from this household University of Georgia football icon legend here in Georgia, and then now the nominee for the Republican nominee for the Senate in Georgia. He is not only a close personal friend of the former President Donald Trump but was someone that the former president immediately wanted to challenge Raphael Warnock, rather early in the primary. As early as summer of 2021, we were starting to hear whispers of the possibility, the very real possibility of Herschel Walker's entry to the race, and as soon as he did declare his candidacy, he was on a glide path, really, to the nomination.

Again, obviously a very big household name, and that outshined the other candidates in the Republican primary in Georgia. There were a number of folks, including the current Agriculture Commissioner, an ex-Navy Seal who worked in the Trump administration. A number of people who had some pretty significant political bona fides that were just totally outshined by Mr. Walker's star power. By saying he is absolutely a political newcomer, and has not really been on the scene in those circles, but is so recognizable and omnipresent in Georgia culture, that it was just really very easy for him to secure the nomination and his team understood that.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Maya, you went exactly where I was hoping we could go here next, which is that in your most recent piece in The New York Times, you write about Walker's campaign revamp. As you're saying, okay, he's a political newcomer, despite name recognition, which is extraordinarily important in low information primary kinds of elections but talk to me about now that he's on the ballot. What kind of revamp to make this a campaign that looks more like a US Senate campaign, or maybe he doesn't want a campaign that looks like a traditional US Senate campaign?

Maya King: It's a balance between messaging that the Walker campaign and Herschel Walker are outside of the norm, which is pretty recognizable to most voters, including his supporters, but that they would be running an unconventional campaign or running as a Washington outsider. Which many in the GOP want to do, particularly in Georgia. While also making sure that they are appealing to the issues and hitting all of the talking points that the Republican base wants to hear.

This week, we saw Mr. Walker go on a tour of a number of farms around Georgia, talking with farmers and rural voters. He will also in the coming weeks be talking with members of law enforcement and veterans. These are groups that are very important to the Republican coalition in Georgia and these are the groups that tend to not only turn out in high numbers but also encourage other members of their communities to turn out.

That was not the case. This was not the plan, that reporters at least were able to see just two or three weeks ago. The campaign after a series of gaffes that Mr. Walker made rather publicly went underground. We, reporters, did not ever receive media advisories for his campaign events, we had to seek them out ourselves.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Professor Gillespie, I'm wondering if this matchup looks familiar to you at all. I lived in Chicago during the 2004 US Senate race between former President Obama who at the time was a state senator running for the US Senate and Alan Keyes, who was actually recruited into Illinois to run against former President Obama. In some ways this is quite different, in other ways to me, it feels familiar. Does it read as similar to you?

Andra Gillespie: I think it does, and I highly recommend to your readers your article that you wrote with Jane Jonna about these things in the Journal of Black Studies if I call. There are some similarities. I think it's important to point out that this isn't the first Senate race where both the Democratic and the Republican candidates are Black. It's not even the only one this year. It's happening in South Carolina as well during this election cycle with Tim Scott being the incumbent senator. There are some things that are similar.

Herschel Walker lived in Texas before resuming his Georgia residency in order to be able to participate in this particular election. That's similar to what happened in the Keyes Obama race. Alan Keyes was recruited out of Maryland to come to Illinois. I think there's also the question about whether or not Republicans either explicitly or implicitly liked Herschel Walker as a candidate because he was African American, so it blunts the charges of racism that were used in the campaign. I think the dynamics though of this are going to be a little bit different.

One, Georgia is a more competitive state electorally than Illinois was and so the margins of this race, regardless of who wins are probably going to be pretty narrow within five points or so. Walker does have ties to Georgia in ways that Alan Keyes did not have them in Illinois. I think racial issues are going to be more explicit, but they're going to be different than they looked in the 2020 cycle. Kelly Loeffler invoked Jeremiah Wright, to try to make Black liberation theology an issue in the campaign and to racialize Raphael Warnock as being dangerous and militant.

I expect that Walker is going to invoke religiosity in the Black church and in some way, even despite the fact that we now know that he had three children out of wedlock that he didn't publicly acknowledge until a few weeks ago. It's going to look a little bit different so I don't expect Jeremiah Wright to make a reappearance in the campaign, but I do expect that some notion of religion and authenticity are going to come to the fore of this campaign.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Yes, this language about religion help us dig in there a little bit. Obviously, Reverend Warnock is a Christian minister, but there's a way that particular political spaces have come to be understood as the moral or ethical positions, whereas no matter what Reverend Warnock's actual position within the church is, somehow it can get framed around the politics of it as therefore being unethical, immoral, or unchristian. Can you just maybe walk us through ways that those appeals might in fact resonate for voters?

Maya King: Sure. In the 2020 cycle, Kelly Loeffler invoked a Black liberation theology to try to signal to voters who might be impressed by the fact that Raphael Warnock is a minister and that he pastors Martin Luther King's church to say that he's not the same type of Christian that you are, so to say he's not practicing white evangelical politics or white evangelical types of religiosity or orthodoxy. It's going to come out a little differently with Herschel Walker, but he's going to say the same thing. Herschel Walker is clearly identified with the evangelical movement.

He talks about his faith in a way that is culturally specific and I think legible to African Americans, but it also resonates very strongly within white evangelical communities. If we think about some of the gas that he said, the AJC a few months ago picked up on a forum that he did at a church where he was talking about evolution, and he said it in a way that for evangelicals who don't believe in evolution but who believe literally in the creation story as it's posed in Genesis 1 is going to resonate. He talks about faith in a very simple way that sounds a lot like storefront preachers in rural churches.

That has potential appeal not just to whites who will feel more comfortable with his version of Christianity than Raphael Warnock's version of Christianity, which talks a lot about justice, but also with Blacks who were socialized in small churches where they didn't necessarily have a preacher like Raphael Warnock who's used to leading big congregations and was trained at one of the best mainline seminaries in the United States. I think it's going to come through in the discussion about abortion.

This was always going to be the case regardless of what the outcome of the Dobbs decision was going to be. All of the Republican candidates talked about the paradox of Warnock being a pro-choice pastor. I expect that Walker is going to deploy that at some point in an attempt to try to mobilize pro-life voters, to say that regardless of my problems, this person has a position that for many single-issue voters, they would view as a nonstarter.

[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: You two, stay right there. We're going to take a pause for a moment. More on the Georgia Senate race is just ahead. This is The Takeaway. All right. We're back, and we've been previewing the US Senate race in Georgia between incumbent Democrat, Raphael Warnock, and Republican candidate, Herschel Walker. Still with me are Maya King from The New York Times and Andra Gillespie from Emory University.

Now, Professor Gillespie, there was talking about the legibility of Herschel Walker to African American voters, which is not to say that he'll get a majority of the African American vote, but in such a tight race, he very well may need just a very small portion. I don't want to do horse race coverage here, but I do want to understand what you as a reporter have maybe heard from African American voters who might not typically cast a vote for a Republican. Is there a sense that Walker could be an interesting candidate for them?

Maya King: On the margins, there's the possibility that Mr. Walker could chip away at Senator Warnock's overwhelming support from African Americans in Georgia and in talks with the campaign and other Republican strategists in Georgia, the group that they are counting on for Herschel Walker to make at least marginal inroads with would be Black men in Georgia, the Black women would remain the most loyal and active democratic voters, so did not do very much in the way of appealing to that group.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Professor Gillespie, I want to give you a chance to weigh in on that as well.

Andra Gillespie: I expect that the normal patterns of Black voting behavior are largely going to [unintelligible 00:14:31] to form in this election. I expect Raphael Warnock to get 90% of the Black vote plus or minus a few percentage points either in. I do expect that there will be a gender gap because we've seen it in national elections over the course of the last decade. I do expect that Black women are going to vote more democratic than their Black male counterparts. I think that will hinge on a couple of things. One, Walker really isn't making a lot of serious overtures towards the African American community. I will note that here, locally, and this does air nationally, he made a point to reach out to Killer Mike.

His campaign doesn't look like say Michael Steele's campaign look in 2006 where Steele very actively reached out to African American voters and engaged African American issues. Ultimately, the problem for Walker is going to be, he's not engaging race in a way that I think is going to be very meaningful to African American voters, particularly in the age of Black Lives Matter. He seems to want to [unintelligible 00:15:32] or deny the existence of systemic racism. He uses talking points to talk about the ways in which he's pro-law enforcement and other things that I think many African American voters will find troubling.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Maya, can you also situate this within the context of what else is happening in Georgia in this election cycle? Obviously, we're not in a presidential election cycle, so the very top of the ballot is not there, but Georgia really is at the intersections here in that having both a gubernatorial and a US Senate race at the same time these two enormous statewide elections. Can you help us to understand how that might affect issues like turnout and vote choice?

Maya King: I think the biggest thing that Democrats are having to contend with right now in Georgia are the national headwinds, particularly as it relates to the economy and inflation. That is the message that Republicans are pushing repeatedly, trying to tie both Raphael Warnock and Stacey Abrams to all of the problems taking place, not only in Georgia but across the south and across the region. Saying that if these candidates were elected, that they would only bring democratic policies to the state and continue the issues that voters are seeing on the ground.

However, in the last week, after a federal court ruled that Georgia's abortion law that would make abortions illegal six weeks into a person's pregnancy, that has changed, I believe, a little bit, particularly on the governor's side, on top the ticket, the direction of the campaign. One thing that Stacey Abrams said in a press conference addressing this new law was that the economy is temporary, economic conditions, ebb and flow, but this law is now permanent. What you need is a Democratic governor with a veto pen who can at least brunt the worst in terms of the impacts of this law.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Professor Gillespie, just in the land of social media, in the milieu of public responses to Herschel Walker's campaign, I do sometimes catch this whiff that he's not to be taken seriously. Any advice for maybe more casual campaign watchers about how to read a campaign, how to think about the ways to see it through a lens that is not purely ideological?

Andra Gillespie: I would caution against doing that. I think people underestimate Walker at their own peril. Donald Trump has tapped into something that I think is an incomplete view of the world and that he does like candidates with sizzle. That was part of what was going on, and the sizzle actually mattered. Just ask people like Gary Black who lost the primary about how far sizzle can take you. It can't take you all the way, but it could definitely get you partially there. In an era of hyper-partisanship and polarization, the fact that Walker is wearing a Red Jersey is probably going to get him at least 45% of the vote.

With mobilization and get-out-the-vote efforts and coordination across campaigns, this is actually going to end up being a really close election. What that means is that Democrats can't take any aspect of the campaign for granted. They can't drop the ball on mobilization. They can't drop the ball on pointing out contrasts and attacks, and they can't just let every gaffe or scandal lie and not actually address the issues, whether it's being on the defense or being on the offensive in this race.

Georgia's just a really close state where we have probably close to equal numbers of Democrats and Republicans. Democrats are probably still the underdog in this race. It's going to take every effort that Democrats can muster in order to propel Senator Warnock across the finish line in a victorious position.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Andra Gillespie Political Scientists at Emory University and Maya King of The New York Times, thank you both for taking the time with us today.

Andra Gillespie: Thank you.

Maya King: Thank you.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.