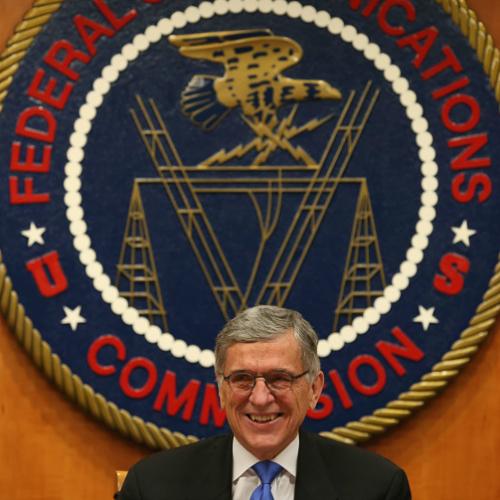

Brooke: From WNYC in New York this is On the Media, Bob Garfield is away this week, I’m Brooke Gladstone. On Thursday, the FCC voted three to two along party lines in favor of net neutrality, reclassifying broadband Internet as a telecom service, like phone lines. The “Open Internet Order” delivered this week also bans Internet Service Providers from giving faster connections to websites that pay for the privilege, or slowing connections to websites that don't. Here’s Tom Wheeler, chair of the FCC.

Wheeler: This proposal has been described by one opponent as quote “a secret plan to regulate the internet”. Nonsense! This is no more a plan to regulate the internet than the first amendment is to regulate free speech. (Cheering) They both stand for the same concept! Openness. Expression and an absence of gatekeepers telling people what they can do, where they can go and what they can think.

Wheeler took note of the unprecedented four million citizens who took the time to send their comments to the FCC, overwhelmingly in favor of net neutrality. That was a triumph in and of itself for a drawn-out tech policy debate. Siva Vaidhyanathan, a media studies professor at the University of Virginia, is cheering too.

Siva: After years of wrangling and debate and hemming and hawing, the federal communication commission finally decided to reclassify broadband, first of all as being fairly fast - basically the speed that lets you watch youtube videos - and that matters in terms of determining how much competition there is out there. If you classify broadband as being very slow, like DSL, then you can imagine that a lot of americans have choices. When they really don't. It makes sure that its very clear to congress, very clear to everyone who matters, that for most americans there really is no competition and no choice in broadband providers. If we had real competition, we wouldn't need regulations like this necessarily because the company that cheated would get punished in the market (that's the theory anyway). But the most important reclassification is reclassifying broadband internet, high-speed internet like a common carrier, like the phone company. Phone companies don't favor one producer of voice signals over another. What we really needed was for the data flowing out of our walls to be treated the same way. So I think this is a major victory, one that I never would have predicted - I'm usually much more cynical about how all this stuff is gonna go down.

Brooke: On the other hand, not to give your cynicism short shrift, you mentioned, as many others have, that this is just the first step. This will inevitably end up in the courts where it will be battled all over again. Are those people just raining on the parade?

Siva: When a federal appeals court struck down the previous attempt at network neutrality rules, the court made it pretty clear that if the FCC decided to reclassify broadband under title II, everything would be cool. So there will be legal challenges, but most of those legal challenges will be about the details of the execution of the regulation, but not necessarily about the heart of it. The heart of it being reclassification. More likely we're going to see congress make another run at curbing the influence of the FCC because that's where the lobbyists really work. The lobbyists don't have any influence over the court system. And this time, Congress wasn't in a position to make a stand, largely because of the the public uproar in favor of network neutrality, but they'll just wait for a quieter time and they'll chip away at it.

Brooke: The last time I spoke with you it was January of last year, after what many decried as a death blow to network neutrality, the DC circuit court of appeals had struck down the FCC rules. When we spoke, you basically said that it was pretty much irrelevant. Why don't we replay that.

Siva (from January 2014): I look at the real decision makers in our information ecosystem, and I see four big companies today. I see Apple, I see Microsoft, I see Facebook and I see Google. And I say, what do those companies want. They aren't necessarily in the business of mastering and monitoring and monetizing what comes over your desktop computer, or even your mobile phone. They want to run the operating systems of your life. They see a time, in the not-too-distant future, where so many different articles in our lives will have data flow through them, and they want to be able to monitor and monetize that data flow.

Brooke: So - do you still think now that this vote has passed, that the time has passed for the issue of net neutrality?

Siva: What's really significant about this week's decision to codify network neutrality, is that for the first time, it explicitly covers wireless. So that buys us more time and makes this network neutrality provision a lot more relevant for the next five or six years. But what's depressing to me about the network neutrality drama up to this point is that it took so long to even rise to the point that we had an informed, intelligent debate about it in this country. Once we got there, it became really clear to everybody that we really needed to do this. If you weren't cashing checks from comcast, it made sense to support network neutrality. And thats fortunately where we are today. But we should get beyond net neutrality. We should get beyond the desktop. Even beyond the mobile phone. And think very critically about the sorts of technological challenges we have in the next 5-10-20 years. They're going to dwarf the debates of the past.

Brooke: What are the other issues that you so ominously refer to that require further regulation?

Siva: Look, increasingly, through our mobile devices, through wearable technology, and soon through our automobiles, we are going to face a concentration of power as one or two companies rise to control the flow of data through our lives. The reason that network neutrality doesn't matter to any of that ultimately, is that this new data network that we misnamed the "internet of things" is not at all like the internet, and it will have to be highly secure, it will have to be controlled by maybe one or two companies, and its going to involve all sorts of challenges as we find human bodies being tracked and monitored and perhaps that data being exploited or leaked.

Brooke: You know, right now, we have the technology that can go into your car, and make it crash, while you're in it. And you have no control over it. That exists right now! What essentially, will be at the heart of the next debate over the data that flows over the internet?

Siva: What we're going to see in the next few years is the control over our bodies as we surrender and outsource decision making to algorithms, data sets, we are going to come up with conflicts and challenges that we can't even articulate yet. But I can definitely say that the sense of for instance ownership over the data we produces - a sense of how open this data will be to state intervention or state examination - we're going to have all sorts of questions over the values that are embedded in these algorithms that are going to make these decisions and figure out whether we're going to have more orange juice in our fridge because the fridges are telling us we're out of orange juice. Well, maybe our fridges can tell us what kind of orange juice, or what brand of orange juice, and maybe there's a contract involved in that - thats going to affect advertising, that's going to affect consumer choices, its going to affect nutrition, there are going to be all sorts of questions of control that come out of these data flows. As you said we're on the precipice of facing these. We already have these technologies in our lives, they're not widely distributed, and my fear is that from a regulatory point of view, we're not mature enough to handle this yet.

Brooke: Well, thanks.

Siva: Anytime, Brooke.

Brooke: Siva Vaidhyanathan is a professor in the media studies department of the University of Virginia and the author of The Googlization of Everything (and why we should worry).