BOB GARFIELD: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield.

AMANDA ARONCZYK: And I'm Amanda Aronczyk.

BOB GARFIELD: Who reports on health for WNYC, sitting in for Brooke this week to focus on infection.

[CLIP]

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: The level of alarm is extremely high.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: New concerns this morning, after the first measles death in this country in more than a decade.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: We have news tonight about the explosion of the West Nile virus.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: So far in the US there are more than 30 cases detected in 11 states and the District of Columbia.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Forty-one people have died and infections are multiplying at four times the usual rate.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: This is the deadliest outbreak on record. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: While political rhetoric focuses on phony threats from asylum seekers and undocumented workers, at any moment, our security is genuinely vulnerable to other outsiders–namely pathogens, microorganisms that cause deadly infectious diseases. Some threats to the American public are overblown, as we shall see. For instance, the Ebola outbreak that ravaged pockets of West Africa and set off a panic when it crossed our borders claimed only a few victims here. On the other hand sometimes the alarm is all too justified. We are now marking the 100th anniversary of the 1918 flu pandemic which was a global catastrophe claiming between 50 million and 100 million lives.

AMANDA ARONCZYK: Scientists are unequivocal. Like a 100 year storm, another pandemic is inevitable. And so in the centenary of the 1918 flu, this week we look at our vulnerability which depends not only on vaccines and antibiotics and other scientific knowledge but on politics, messaging and public trust. At a historical moment when no fact is immune from political spin and science itself is under attack. How will medical knowledge, human nature, fake news, dark politics and the lessons of history converge to determine our fate. We begin with the flu of a century ago. A world event so cataclysmic that over the years its enormity grows and grows as if the pile of dead bodies itself is mounting over time.

LAURIE GARRETT: All the numbers that have been attached to the size of the death toll of this pandemic were based on extrapolations from what was known in the few parts of the world that had record keeping and health departments to do that sort of thing.

AMANDA ARONCZYK: Laurie Garrett is a science journalist and the author of The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World Out of Balance.

LAURIE GARRETT: So that was the official tally for most of the 20th century. And then people started thinking, 'wait a second. There were cases in China which was a huge country. There were cases in India which was a huge country. How come we don't have the numbers?' And it's actually not until pretty much the end of the 20th century that you start to have really scrupulous attempts to figure out how massive had the global toll been. And then the toll starts to jack up to somewhere between 75 and 100 million. I mean this whole parts of the planet that weren't even counted like most of Africa. As far as we can tell, there was no place on earth that missed the 1918 flu.

AMANDA ARONCZYK: For more than a year, the flu was the overarching reality of daily life on Earth.

LAURIE GARRETT: There are any number of reports to be found where an individual got on the subway in Coney Island and was dead by the time they reached the Upper East Side. It was hemorrhagic. People's bodies turned black. They had internal bleeding. They coughed up blood.

AMANDA ARONCZYK: As if the brutal violence to the body wasn't enough, the pandemic came at the tail end of the first world war–what was then, the world's deadliest.

LAURIE GARRETT: So there already was a sense of trauma and grief going on in the background. Along comes this plague. My uncle was a 5 year old when the epidemic started in Baltimore. All the schools were closed in Baltimore. And his father ordered all the children to remain inside the house until whatever this is ends. So for months, they were locked basically inside the home and his job as a little boy was to sit in a certain place by the front window and keep a log of hearses coming down the street and see if you can identify how many caskets were pulled out of the neighbor's houses. Imagine that was his job.

AMANDA ARONCZYK: And yet incredibly, unimaginable as it may seem in today's breathless hype filled media environment, the overarching story of life on Earth wasn't big news.

LAURIE GARRETT: It's interesting because as the flu rolled out across the nation, it's remarkable when you go through old newspapers to see how little coverage it actually got. And I think everybody who's ever dug into the history of 1918 has been struck by this. There is only a, you know, a few newspapers that were really dedicated to the story. And of course there was no such thing as a science reporter or a health reporter. These were written by the same guy who yesterday was covering a brawl in a high school gym, you know?

BOB GARFIELD: And so while countless families were burying the dead, even the yellowest of the yellow press were burying the lede.

NANCY TOMES: You have to wonder had an epidemic like that occurred without The competition from the war that it would have had more attention.

BOB GARFIELD: Nancy Tomes is a historian and author of The Gospel of Germs: Men, Women and the Microbe in American Life. I asked her, given that these were the wild west days of Pulitzer and Hearst, was the coverage responsible?

NANCY TOMES: My sense is that given the potential to play the yellow journalism card here, that the coverage of the epidemic was relatively restrained. That's not to say there wasn't criticism published of specific acts. The Commissioner of Health in New York City, you know, there's some grumbling. He does this, he does that but the sensationalism was on the strictly political side. Machine politics setting Tammany Hall against this, that reformer. That kind of political fodder and less making a sensational bid to undermine the authority of a public health department.

BOB GARFIELD: What were people told to do to manage the spread of the infection?

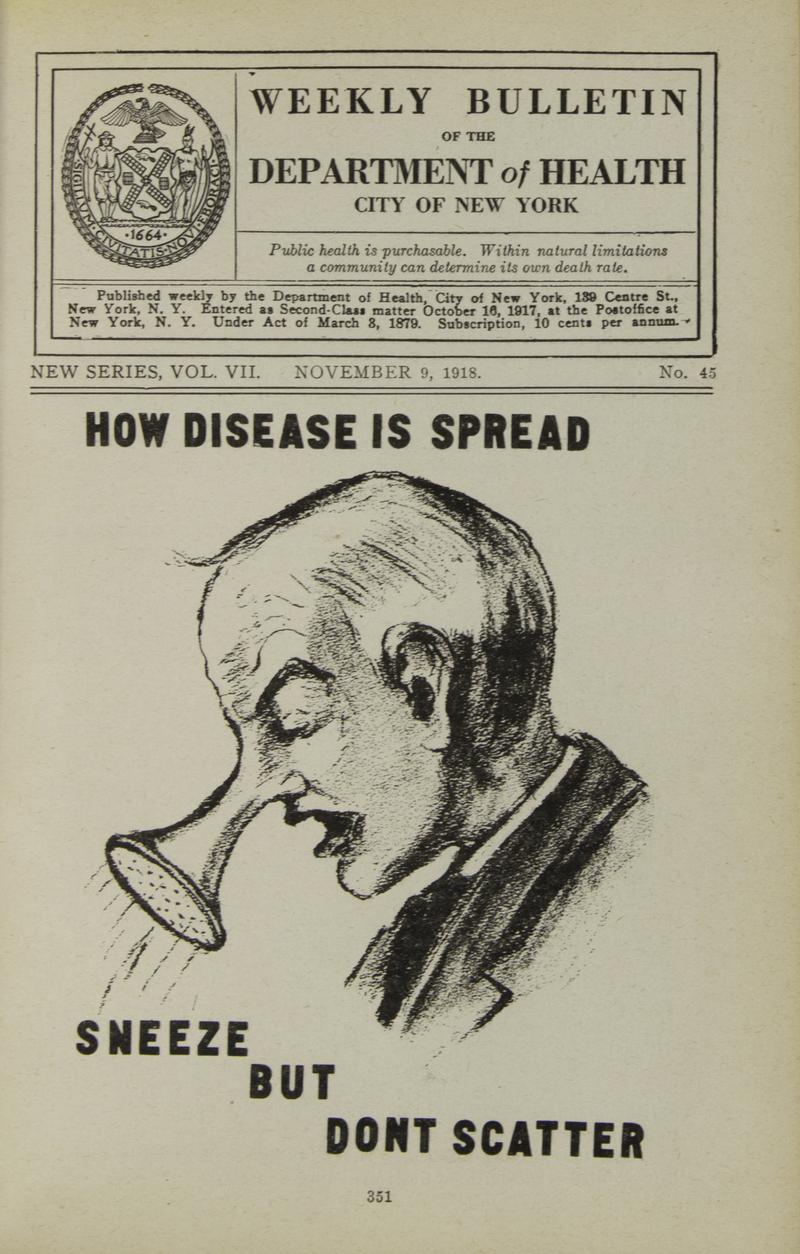

NANCY TOMES: In fact, the basic tools of managing an influenza epidemic were taken out of the tuberculosis toolkit. You can kind of take posters that were anti-tuberculosis posters and you see them just being retrofitted with, 'be careful of how you sneeze to avoid getting the flu.' But tuberculosis is not highly contagious. So, with an influenza epidemic, because it is so much more contagious, really the smartest thing you can do, and still do, is to stay home.

BOB GARFIELD: I want to ask you about the mechanics of public health messaging. What did the public health authorities do to tell you to quarantine the ill, to tell you not to cough in somebody else's face, to get this information out?

NANCY TOMES: So they were borrowing a lot from the American advertising in this time period. So they would try to come up with an ad equivalent for cover your mouth when you cough or don't spit on the sidewalks. They also did as much as they possibly could education. So, little kids start to get this kind of training. There are these hysterical photos you can find of little kids being put through a handkerchief drill, you know, to teach them how to sneeze right. If someone did get sick in your family and you were in a working class immigrant, you would get a public health nurse sent to you and that nurse would explain a lot of this stuff to you.

BOB GARFIELD: There are a number of historical watersheds that are deemed to have changed the society. Did the flu pandemic of 1918 change American society?

NANCY TOMES: This has been a big bone of contention because there's a famous book about the pandemic that basically said it was repressed. It was extremely traumatic. I can remember members of my family talking about it, experiencing it. So it wasn't like it disappeared entirely but there's just so much going on–seeing all of these young people die, how that intersects with stories about veterans coming back and discussing what it was like fighting in that trenches. So I think it all gets kind of muddled up in a way that makes it hard to pull out the influenza as a cause by itself.

BOB GARFIELD: Nancy thank you.

NANCY TOMES: You're welcome, take care.

BOB GARFIELD: Professor Nancy Tomes is a historian of health and health care at Stony Brook University.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER].

AMANDA ARONCZYK: Coming up, over reaction and under reaction.

BOB GARFIELD: This On the Media.