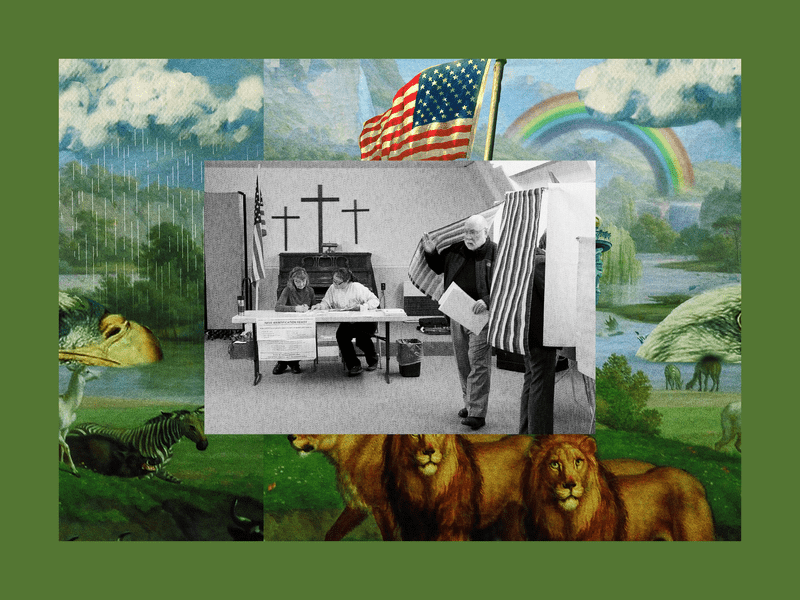

How The Evangelical Machine Got Made

( AP Photo / Ted S. Warren )

A transcript of this episode is presented below:

(A soft indicator sound, like the “Fasten seat belt” notification on an airplane, intones one note over the quiet hum of recycled air.)

Emma Green: I’ve been thinking a lot about the way that little actions by a single character really do have the power to change history. And I think that’s this story.

Julia Longoria: Emma Green is a staff writer at The Atlantic.

Green: I write about religion and politics mostly. All the uncomfortable stuff.

Longoria: She recently told me a story about a moment I’d never heard of—but one that turned out to have huge consequences for the country.

Green: Okay. Hear me out. Hear me out. I get that it sounds implausible, and other people might tell this story differently, but I think that there is a strong argument to be made that one of the biggest things that’s happened in the last half decade—which is that Trump got elected—that that happened, that was finalized, that was cinched, in the middle of this Tom Hanks movie.

Longoria: (Chuckles lightly.) Okay, tell me what happened.

(Sparse percussive music enters and slowly builds in the background.)

Green: So it happened in October of 2016. The 2016 election was really neck and neck. People weren’t sure what was gonna happen. Trump had kinda come out of left field.

Ralph Reed: I don’t know. It was probably about 4 or 5 o’clock in the afternoon, on a Friday afternoon.

Green: It has to do with this guy named Ralph Reed. He’s a political operative, and has kind of become this spokesperson for the Christian right. You could maybe think of him kind of like “Mr. Evangelical.” And he had just finished a long day at work.

Reed: So I went to a movie theater, and I was watching the film Sully, with Tom Hanks …

Tom Hanks: (As Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger.) Birds. (The sound of birds cawing, then an impact, then an explosion".)

Reed: Which, incidentally, is a great movie. And he’s terrific in it, as you can imagine.

Hanks: (As Sully.) Mayday! Mayday! Mayday! This is Cactus 1529. Hit birds. We’ve lost thrust … (Movie audio fades out, except the sounds of Mayday signals, which continue lightly.)

Reed: (Interrupted periodically by a cellphone’s vibrations.) And I was in this film, and my phone kept buzzing incessantly. So I was getting all these text messages and all these calls, and I thought to myself—after about 15 minutes of this, when it wouldn’t stop; it was in my pocket—I just went, “Good grief! I mean, has somebody died?”

Hanks: (As Sully, echoing.) Brace for impact.

Green: So finally he pulls out his phone, probably starting to annoy his neighbors in the theater.

Reed: (Over the sound of an iPhone unlocking.) And I crouched down in my seat, and I started scanning through my text messages, and it was The Washington Post, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Associated Press, Religious News Service [Laughs.] wanting a comment on this video.

(Indistinct audio from the movie plays for a moment.)

Reed: And I thought—well, it was a really great movie—so I thought, Well, I really don’t want to get up and leave in the middle of this movie.

Green: He’s like, Okay. What could this video be?

Reed: So I—I hit the video on the Washington Post website, and I leaned in real close so I could hear the audio.

Donald Trump: (From the Access Hollywood tapes, over the sounds of camera shutters.) I gotta use some Tic Tacs just in case I start kissing her …

Green: You can probably guess. This was the Access Hollywood tape where [Inhales.] there was footage from many, many years ago.

Trump: (From the tapes.) And when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything …

Green: Where Donald Trump made lewd comments about grabbing women by the—I don’t know if I can say that on the radio.

Longoria: Let’s skip it. (Laughs awkwardly.)

Reed: And so that I could be sure that I got it, I watched it and listened to it twice.

(Light, atmospheric electronic music plays.)

Green: He had this decision to make. He hadn’t talked to anybody. He was literally in a black box. He had to decide what evangelicals were going to do now that they’d heard this tape of their presidential candidate—their preferred candidate—saying some really offensive stuff.

Reed: Does this mean that we should either repudiate Donald Trump, stay home, cast a protest vote, vote for Hillary? As civic and political actors, what is our responsibility?

Green: In that moment, Reed was being asked what evangelicals thought—but he was also telling them what to think. When they opened up their newspaper the next morning and saw that quote from Reed, it would be a signal.

Reed: And I then tapped out a statement that I then sent to every news organization that had contacted me. And I have to tell ya, I didn’t necessarily think I was right.

Green: What he wrote in that statement? That’s what this story is about.

(The music shifts to introduce a mechanical-sounding melodic line from a piano.)

Green: There are so many things we believe we know about religion and politics—that white evangelicals have always been Republicans, or that Republicans have always been pro-life. We think we know, we think it’s obvious, why evangelicals supported Trump and what the consequences have been.

But actually, this is a story that could have gone a lot of different ways. And I think the reason why Ralph Reed is so interesting is that he was the guy behind the scenes who directed the course of history in a big way.

(The sound of an airplane flying overhead overwhelms the music, bringing silence in its wake. Then bouncy, clanky percussion sets up a slow harmony over jungle ambience.)

Longoria: Over the next two weeks, Emma Green brings us the story of a behind-the-scenes project. It’s the story of how one man took a disparate, disorganized group of believers and turned them into one of our country’s most formidable political machines—and the story of what was sacrificed along the way.

I’m Julia Longoria. This is The Experiment, a show about our unfinished country.

(A moment of music, then quiet.)

Green: The story of Ralph Reed’s political career starts back in the early 1980s, when the religious right as we know it today was still in its infancy.

Reed: I was kind of a work-hard, party-hard kind of guy, and that was the culture in Washington.

Green: He was 22, working as the executive director of the College Republicans, organizing for Ronald Reagan. He was already a rising star in conservative politics. But the Republican party hadn’t yet become synonymous with the religious right.

Oscar Brand: (Singing “Why Not the Best?,” Jimmy Carter’s campaign song.) He spoke straight and simple, and I began to understand … (Fades under.)

Green: In fact, the guy who first got everyone talking about evangelicals in politics around this time was a Democrat.

Brand: (Singing more of “Why Not the Best?”) We need Jimmy Carter! Why settle for less, America? (Fades under.)

Green: Jimmy Carter was very publicly born-again. He was an evangelical. At this time, evangelicals had a different image than what most people might think of today. It was a little bit hippie-dippie. It was people out there on buses trying to win over hearts for Jesus. It was this countercultural movement that a lot of elites in Washington didn’t take seriously.

Reed: I had grown up in the church, but I had never really wanted to be viewed as, quote, “one of them,” you know? I didn’t want to be seen as crazy; I didn’t want to be seen as a nut.

Green: But as Reed was going around trying to organize the “Reagan Revolution,” he started to feel like something was missing in his life.

Reed: I was working with a lot of people that, on some instinctive level, I came to see were not happy. And one of those people was me. And yet, in the process of this, I was encountering a lot of young Christians, and they were happy, and they were, you know, effervescent, and they had something that I wanted.

Green: The answer to his emptiness came to him one night in September of 1983, when Reed was out at a bar with some of his colleagues.

Reed: I was at a watering hole on Capitol Hill called Bull Feathers—you know, kind of a bar and tavern. And we were just doing what we would normally do on a Saturday night, having dinner and drinking. And I really don’t know to this day why the idea occurred to me, other than the fact that I was feeling a spiritual yearning and feeling an emptiness. And, um, I just decided, you know, “I think I’ll go to church tomorrow.” And I walked out to a phone booth.

(Soft electric-guitar music gives a kind of solemnly mystical energy to the moment.)

Green: When he got there, he ran his finger down the page of a phone book.

Reed: I went to Churches, and then I went to Evangelical, and I found a church just outside Washington, and I went there the next morning and sat in the service. And at the end of the service, the preacher did an altar call.

He said, “I don’t know who you are. I don’t know how you got here today. But I want you to understand, whoever you are and however you got here, that this is not an invitation; this is a command.”

Green: Wow.

Reed: And those words changed my life.

Green: This is what it means to be born again. There are tons and tons of different kinds of evangelical churches, and they don’t all have the same theology or even sound and look the same. But generally, evangelicals all share the kind of experience Reed had—a moment of conversion where they become a Christian. There’s this idea of being a fool for Christ, standing unashamed of your faith, even when other people question you. Not long after his conversion, Reed was back in the office with the Reagan Revolution crew, and he faced the first test of his new faith.

Reed: You know, it was just just young people sitting around the office, and somebody was ridiculing anybody who believed in creationism.

Green: Hmm.

Reed: And I just remember I was [Laughs a little.] sitting at my desk, and I had literally probably been a Christian for about, you know, two or three weeks, and I looked up from my desk, and I said, “I believe it.” And I just remember them all looking at me with shocked [Laughs.] expressions on their faces. And they say, “You really do?” And I said, “Yeah! I believe it!”

Green: Hmm.

Reed: And so, yeah, I think it was something that I wrestled with—something that I’ve always wrestled with—of how do you deal with that kind of reaction: “You really believe that? You believe there’s a hell? You believe there’s a devil? You know, does he—does he have horns? Does he have a tail? Boy, you’re a weirdo.” Nobody wants to be viewed that way, you know, if we’re honest.

Green: Ralph Reed’s conversion was happening at roughly the same moment that the Republican party was going through a conversion of its own.

Jerry Falwell: We began, in this country, a move away from the value system on which this nation under God was founded …

Green: A group of religious leaders began to talk about how the country had drifted away from God. They saw a nation overtaken by secularism, abandoning the Bible’s teachings. And they started to strategize about harnessing the power of conservative Christians in politics.

The public faces of this movement were men like Jerry Falwell, who founded Liberty University, which trained up young warriors for Christ.

Pat Robertson: And we said, “We know that our nation is in trouble …” (Fades under.)

Green: And Pat Robertson, the godfather of televangelism, whose image was beamed to Christians across America on The 700 Club.

Pat Robertson: We want to come back to the Bible and back to God. And if we don’t turn, we face crisis and chaos, and that was the message. (Fades out.)

Green: Most of these men were white and had deep roots in the South. They wanted to build influence for people like them: largely white Christians from very conservative Protestant churches who felt like they were getting pushed out of public life.

They focused on a list of issues, like bringing prayer back to public schools and stopping the spread of pornography. They were angry about what they saw as government overreach, including regulations that denied tax-exempt status to racially segregated private schools.

This was Reed’s training ground, both as a political operative and as a young Christian coming up in the religious right. And in 1989, he went to a conference filled with the heavy hitters of the conservative movement.

Reed: And I happened to be seated next to Pat Robertson, who had just run for president. I figured I’d never meet him again, and so I proceeded during this dinner to tell him everything I thought he had done wrong when he ran for president.

Green: After the dinner, Pat pulled him aside.

Reed: And he said, “Follow me.” And we walked into the kitchen—the banquet kitchen—and there were all these plates and pans clattering, and they were clearing all the plates off the tables, and the waiters were running in and out, and he and I are standing [Laughs.] in this kitchen, and he said, “Listen, I’d like for you for you to come and work for me.”

Green: Robertson explained that he was going to start a new organization that was going to carry the torch of the religious right. He asked Reed if he wanted in. And eventually, Reed said, “Yeah!” Robertson laid out his vision for what he wanted Reed to do.

Reed: And he said, “I want you to take notes.” And he said, “This is our goal …”

(Gentle piano music plays.)

Reed: “Operational control of at least one of the two major political parties. Elect a committed Christian as president of the United States, take a majority in Congress and the U.S. Senate, elect a thousand committed Christians—devout Christians at every level of government. This isn’t just going to be some Christian civic group. This is going to be the most effective public-policy organization in the country. And at the end of 10 years, American politics is going to look totally different.”

And I’m sitting here [Laughs.]—I’m sitting here taking notes, and I’m about to pass out.

Green: So was this daunting? Did you look at this and say, “Holy moly, I just volunteered myself to try to build the biggest grassroots network of evangelicals in American history”?

Reed: Well, you know, Pat had a sign in his dressing room, in the studio where he did The 700 Club, and it said Attempt something so big that, unless God intervenes, it’s destined to fail.

Green: Hmm.

(The music plays one final note.)

Green: In 1989, the idea of organizing Christian voters into a political force wasn’t exactly new. The Black church was hugely influential in the ’50s and ’60s in securing the wins of the civil-rights movement. And before that, churches were central in things like the temperance movement, women’s suffrage, and even the abolition of slavery.

Reed: But among the theologically conservative churches—for lack of a better term, the fundamentalist and the evangelical churches—that was not the case. From the time of the Scopes trial, in 1925, when they suffered the humiliation of being seen largely as boobs and hayseeds and Neanderthals and anti-intellectual and anti-modernist, until—really—the late ’70s and early ’80s, those fundamentalists, Southern Baptists, and evangelical Christians largely had their noses pressed against the glass of the political culture.

Green: Reed’s mission was to tap this untapped resource. And so he built a political platform that would appeal to those groups. It was pro-life, focused on traditional family and bold expressions of faith in public life. Reed packaged this as the “pro-family agenda.” Then he went out to recruit believers.

(Persistent, up-tempo synthesizer music begins to play.)

Reed: We started with the idea that there were roughly 200,000 Bible-believing or evangelical churches in the country—that there was somewhere between 40 and 50 million people who were members of those churches or affiliated with those churches.

Green: But to get those people organized, Reed had to start from scratch. He began by gathering up church directories with lists of names and phone numbers.

Reed: And anybody who was a member of an evangelical church who wasn’t registered to vote, we called them, and we showed up at their house, and we got them registered to vote.

(Music becomes clearer, less distorted, and louder.)

Green: He didn’t just want a list of names, though. He wanted to build a group of people who knew how to do politics.

Green: We taught people how to build a precinct organization; how to do a voter registration drive in your church; how to make sure you were educating voters in a way that didn’t violate the tax-exempt status of the church; how to do a get-out-the-vote effort; how to write a news release. I mean, this sounds very basic, but for evangelical Christians who had never done anything politically in decades other than go to a rally at a church, this was all new.

Green: Many of the people Reed was targeting were allergic to the idea that God and politics had anything to do with each other. And so his pitch went something like this:

(Music fades out.)

Reed: The truth is that for people of faith in any society, in any civilization—but especially in a democracy—civic engagement is not something that will avoid you. If you choose to disengage, it will show up on your doorstep in public policies that will undermine and assault your beliefs, and elected officials who don’t share your values. So I think many of them felt that it was almost a defensive action.

President George W. Bush: Faith teaches humility. As Laura would say, I could use a dose occasionally. (Audience laughs.)

Green: All of the work that Ralph Reed did? It worked. In 2000, George W. Bush was elected to office with the support of evangelicals who he reached with his notion of a compassionate conservatism—this idea that promoting small government and helping people were not incompatible values. Bush was one of their own.

Bush: Throughout our history, in danger and division, we have always turned to prayer. And our country has been delivered from many serious evils and wrongs because of that prayer. (Fades under.)

Reed: I remember, uh, you know, the horror of September 11, and when President Bush proclaimed a National Day of Prayer. And I remember he said that we were meeting in the middle hour of our grief.

Green: Reed started running through the names of the people who would have been around Bush in this huge historical moment. The president’s head of speechwriting was an evangelical. The attorney general was an evangelical.

(A persistent beat enters, layered with sporadic electric strings.)

Reed: And that was when it really hit me. I knew at that moment that we were no longer the redheaded stepchild of American politics, that we had graduated to full-fledged participation. We were in the room where it happened.

Green: The Bush years were a sign of Reed’s triumph. He had left the Christian Coalition and started his own political consultancy. But all those old allies of his from the Christian right? They were now some of the most powerful people in the government. This included a guy named Jack Abramoff, who Reed knew from his College Republican days. Abramoff was one of the most powerful lobbyists in all of Washington—he even worked on the Bush transition. Abramoff brought Reed in on some of his projects, which got Reed into some trouble.

The most significant of these scandals had to do with casinos. Abramoff represented a number of tribes who ran gambling outfits. Those tribes faced competition from other casinos and other kinds of gaming in the area. So Abramoff asked Reed to create problems for the tribe’s competitors. Reed’s job was to build opposition on the grounds that gambling is un-Christian, meaning that Reed was rallying religious opposition to gambling while being paid indirectly by tribes who ran casinos.

Later, Reed said that he didn’t know his payments were coming out of casino profits. Here’s what he said at the time: “Had I known then what I know now, I would not have undertaken that work.”

Reed never got charged with any crimes, but his name got dragged through the mud at some high-profile congressional hearings. When Reed ran for lieutenant governor in Georgia a few years later, he tanked—probably because of his association with Abramoff. It was a low point in Reed’s career.

By the time Obama got elected, Reed and the mostly white evangelicals he represented were back out in the cold again. They saw the president as hostile to their beliefs and their way of life.

But then, after all those years of scandals and political exile, when it seemed like Ralph Reed’s chapter in American history was over, he met a man who he thought just might put evangelicals—and his career—back in the game.

(A moment of stillness in the music—a tension.)

Reed: I said, “Donald,” I said, “I don’t know you, and you don’t know me, but if you’re serious about this—” and he said, “Let me stop you right there. I am dead serious about this.”

Green: That’s after the break.

(Music out.)

Green: Ralph Reed spent the Obama years in political exile. But one day in 2011, he met someone who he thought could potentially be a ticket back to the White House.

Reed: I had gotten a call from a reporter who said, “I have been fishing around a little bit, and I think Donald Trump is serious about running for president.”

And this reporter said, “What do you think of that?” And I said, “Well, if he runs as pro-life—which is my understanding of what he plans to do—given the power of his celebrity, his money, his ability to finance his own campaign, and his name ID, which most candidates spend tens of millions of dollars buying, and he will have on day one, I think he will get a fair hearing from evangelical voters. And I think he could surprise a lot of people.” And the guy said, “Do you mind if I quote you?” and I said, “No, I don’t mind.”

And about two hours later, my phone rang. And it was Donald Trump. And, I mean, I couldn’t believe it, but apparently the guy gets Google alerts anytime his name is mentioned in the media—or at least he did then. And he was like, “Ralph,” he goes, “I just called to say thank you for what you said.”

Green: Uh-huh.

Reed: And I said, “Well,” I said, “Donald,” I said, “I don’t know you, and you don’t know me.” I said, “But if you’re serious about this—” and he said, “Let me stop you right there.” He said, “This is not a game. Don’t believe what you read in the media. I am dead serious about this. Do you understand what I’m saying? Dead serious.” And I said, “Okay,” I said, “if this isn’t just a way to get press or build the ratings for your show—if you’re really serious—then you need to get to know the evangelicals, ’cause they’re half the Republican vote.” And he said, “Well, I’d like to do that.” And I said, “Well, I’ll help you.”

Green: Did you think he was personally a Christian?

Reed: Well, I didn’t know that, and that’s not the nature of my relationship with him today. I’m not a pastor. I’m not a minister. I’m not a spiritual adviser. I’m a political operative. But I had a lot of conversations with him about where he stood on the issues, and there was no doubt in my mind that he was genuinely pro-life, that he supported religious freedom, that he was serious about appointing conservative and pro-life judges. He understood that the evangelicals were a key—if he was going to be successful, that he had to connect with them.

Green: So did you help him because you thought that he was going to be a really serious contender, and you wanted to make sure that your people had his ear? Or was it that you felt that he was going to be a great candidate—or a great president—for evangelicals, so you wanted to make sure that he won?

Reed: My thinking at the time—honestly, just boiling it down to honest, brass-tacks politics—I thought, In my career, there’s never been anybody like this guy. I mean, he’s got the money to run for president and write a check and pay for the whole thing. He’s one of the most famous people not only in the United States but in the world. He’s a natural and gifted performer. And I thought that if he got into this thing, it wasn’t going to be a big fish in a small pond. This was going to be a whale jumping in a bathtub.

And if I was right, then this was gonna happen, whether people wanted it to happen or not. If he had a chance of being president, it was very important—in my view—for him to have a good and mutually productive and beneficial relationship with the faith community based on trust. And it was equally important for the evangelicals to have a relationship with him.

Green: To Reed, it was obvious that evangelicals should take Trump seriously. But to other evangelicals, well, not so much.

Reed: They didn’t trust him at the beginning. You know, they viewed him as, you know, he’s given money to Democrats, he’s formerly pro-choice, he’s only been pro-life fairly recently, he lives in Manhattan. You know, that’s not exactly a deep-red precinct.

Green: Uh-huh. (Both laugh.)

Reed: He hasn’t really moved in our circles. You know, his life hasn’t exemplified our faith. The vast majority of evangelicals did not support Donald Trump—either when he got in or during the Republican primaries.

Green: If Reed was going to get anyone even remotely sympathetic to his goals elected to office, he had to bring conservative Christians along. Roughly a quarter of the country identifies as evangelical, and, at least among those who are white, they’re a bloc. They vote, and they vote Republican.

Reed needed to convince evangelicals that Trump could be their guy—that sometimes it’s worth setting aside your moral sensibilities if you can guarantee that someone will represent you well in Washington. Reed needed them to get on board with the idea that your political candidate doesn’t need to be your Sunday-school teacher.

Reed: I said, “Look. You’ve got to think the way the Black community thinks, and you’ve got to think the way the Jewish community and the pro-Israel community thinks. They don’t think, How do we make sure our guy wins? They think more wisely and strategically: How do we make sure that there’s somebody within our community, close to every one of these candidates, so that when one of them wins, one of our people is in the room?”

Green: So how did you overcome that trust problem and get people to be willing to take a flyer on Trump?

Reed: Well, I think there were three moments that really mattered.

One was the Scalia vacancy. There was a vacancy on the U.S. Supreme Court, and either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump was going to fill it. You had to figure you had a 50–50 chance of getting it right with Trump. And you had to figure you had a zero percent chance of getting somebody who was pro-life with Hillary. So that was a critical inflection point.

I think the second was when he selected Mike Pence.

And then I think the third moment was Hillary Clinton’s “basket of deplorables” comment, which was the line that really, really resonated in the evangelical world—which was “irredeemable.”

She said, “They are irredeemable.” And I think, at that point, I think a lot of even the last remaining evangelical Christians who had a lot of reticence and resistance to Trump went, “Well, gosh. I mean, if that’s where she’s coming from, I’m gonna vote for Trump.”

(Softly flowing sound washes over synthesizers and all, before ducking under the narration.)

Green: Which brings us back to the Access Hollywood tape. Reed had convinced people to get on board. He had sold them on the idea that Trump was the best hope they had. But that video! Wow. It just highlighted all of the things about Trump that a lot of Christians might have felt uncomfortable with.

Reed had to decide what to do. He hadn’t talked to anyone. But he made the political calculation in his head—fast.

Reed: I basically said, “You know, listen. I certainly don’t approve of the language that he used. It was highly inappropriate. But, in the hierarchy of voter concerns—including but not limited to the right to life, the vacancy on the U.S. Supreme Court, the Iran nuclear deal, support for the state of Israel, religious freedom, et cetera—I honestly think that this video, though it’s embarrassing and inappropriate, is going to rank very low on voter concerns.

But I have to tell you, that weekend, all indications were that his candidacy was over.

(The music fades out.)

Green: It’s not like every American evangelical was waiting for Ralph Reed to tell them what to do—most of them have probably never even heard of him. But Reed had the ear of major pastors and giants of the evangelical world. Christians around the country were listening to them to understand how to think about this.

Reed: I mean, I got a call from one of the top evangelical leaders in the country, who was a friend of Donald Trump’s, who told me they believed that it was over and wondered whether or not we should publicly say so.

Green: And so Reed intervened. Again.

Reed: I was on a call with the faith advisory group of the campaign, you know, which was major evangelical leaders. And there were people on that call that were wanting to issue a statement calling on the president to drop out of the race and be replaced by Mike Pence. And I guess it fell to me because I—you know—was more involved politically than some of the pastors and the preachers. And I explained to them he was going to be on the ballot, whether we voted for him or not. In several states people were already voting! And if we repudiate Trump and ask him to step aside and be replaced by Mike Pence, they’ll be a million votes thrown out. Florida’s gone. And if Florida is gone, the election’s gone. And—and that kind of ended some of that talk.

(Heavy, somber music starts to play.)

Green: Many remember this moment as hypocrisy. But this moment was actually a culmination of a movement that had been building for decades. Reed and others in the Christian right had spent years convincing evangelicals to participate in the political process despite their misgivings—teaching them to calculate trade-offs, making them comfortable with the idea that to get what you want, you sometimes have to play a dirty game.

Green: You know, I think this moment matters because it speaks to one of the core questions that has been asked about evangelicals and Trump. You know, you and I could both recite from memory the lede to every article about evangelicals and Trump: “He’s the thrice-married casino owner. He splashed his affairs across the front pages of the New York tabloids,” you know, “How can evangelicals support a man like this?” So I guess, um, why do you disagree when people say, “Aren’t these evangelicals just a bunch of hypocrites?”

Reed: My argument is “Which vote results in the greatest good and redounds to promoting the greatest amount of social justice? And which one advances grave moral evils? And which one will least advance the common good?”

And for me, I speak only for myself. I don’t claim to speak for every evangelical. I wouldn’t be that, um, presumptuous. But for me, the fact that Donald Trump was imperfect—the fact that he had led a less-than-perfect life—was something that I already knew. But when it came to the issues that I believe were moral issues—religious freedom, the right to life, the protection of innocent human life in the womb, the appointment of judges that would respect that life, the defense of the state of Israel and the Jewish state against its many enemies that seek to wipe it off the face of the earth—these are not just policy issues to me. These are issues of right and wrong. On every one of those issues, he pledged to, and kept his word to, advance every one of those moral goods, and Hillary would have done the opposite. And that was why I supported him, and I think it’s why the overwhelming majority of evangelicals supported him.

Green: Arguably, Trump kept his promises to the evangelicals. He nominated three pro-life Supreme Court justices, and dozens more on the lower courts. He showed up at the March for Life. He moved the American embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem—something presidents had long said they’d do, but never actually did.

But, ultimately, the Trump presidency was defined in the minds of many Americans, including a lot of Christians, by his cruelties: separating families at the border, turning away thousands of refugees, constantly trashing his enemies on Twitter.

Green: Did you ever have doubts during his presidency, either about supporting him or specific policies that he championed? And did you see a benefit to having his trust when those moments occurred?

Reed: Uh, I think the—you know, what I would say is, during Trump’s presidency, as with every other presidency that I have been involved in helping to elect that president, there were disappointments. But, to quote Ronald Reagan, an 80 percent friend is not a 20 percent enemy.

So if you want to be involved in politics without ever having to compromise, then you want something that has never existed and never will.

(Soft, smooth, and sad, a bed of strings begins to play.)

Green: But in every compromise, there’s a cost. And in this case, the cost might have been really, really high—a loss that could undermine the entire project Ralph Reed helped to build.

Lecrae: Yeah, absolutely wrecked my faith. It drove my faith into the ground.

Green: That’s Part 2 of this story, next week.

(The music picks up, incorporating a driving guitar line over keyboard.)

Tracie Hunte: This episode was produced by Katherine Wells and Alvin Melathe, with reporting by Emma Green. Editing by Julia Longoria, Tracie Hunte, and Emily Botein. Fact-check by William Brennan. Sound design by David Herman. Music by Tasty Morsels.

Our team also includes Natalia Ramirez and Gabrielle Berbey.

If you enjoyed this week’s episode, please be sure to rate and review us on Apple Podcasts, or wherever you listened to this episode.

The Experiment is a co-production of The Atlantic and WNYC Studios. Thanks for listening.

(The music, and the episode, ends.)

Copyright © 2021 The Atlantic and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.