Episode 6: “When they don’t behave”

Julie Kupchik: The one thing that I can tell you, most of the guys that worked at Carlton Palms, they’re big. They want big guys.

This is Julie Kupchik. She used work at Carlton Palms, the facility where Arnaldo lives, about ten years ago. She saw how the staff there used restraints to physically hold clients down. Keep them from fighting back. She says doing that kind of work, takes some muscle.

JK: But the one thing that I noticed. On their key rings, the guys, the workers, they would all have a little small black baton. Know what I’m talking about?

Audrey Quinn: No.

JK: You know what a police baton is right?

AQ: Oh yeah, like a nightstick.

JK: Mm-hm. Take one of those and take you thumb and your pointer finger and stretch it out.

About six inches long.

JK: They all had those little back batons on their key rings.

AQ: What do you think they used them for?

JK: To bend the fingers back on the kids when they don’t behave.

You’re listening to Aftereffect. I’m Audrey Quinn. In the last episode we got caught up on how Arnaldo’s doing at Carlton Palms. He’s been there since a month after the shooting. And Arnaldo seems happy. But his lawyer has concerns he’s being neglected, his therapist suspects he’s not getting a lot of help there, saw he’s getting restrained for leaving his room at night. And his mom Gladys and sister Miriam are sensing something shady.

On the one hand they don’t like the idea of moving him to another facility — again — but they can’t be sure what was happening to him there. Goodbyes are getting harder.

Gladys Soto: They tell me he’s okay. I need to believe them.

What really goes on at Carlton Palms? When Miriam and Gladys aren’t around? To know what’s actually happening to Arnaldo, I need to know what’s really happening in this place. That’s what I have to find out.

To start, I reached out to Carlton Palms directly about my concerns. Just like they hadn’t wanted to talk about Arnaldo’s time there, they didn’t want to talk about past allegations either.

And we tried. Contacted them from all angles. Sent an interview request with an eight day deadline to a Carlton Palms publicist, who forwarded my email to a superior, along with a note — which he accidentally sent to me instead. “Sounds like we have until the end of next week to either give her the standard blurb or decide on a different strategy.” I requested a different strategy. Ended up with the blurb.

They sent it my producer Aneri Pattani: It reads in part:

“For those who aren't familiar with our work, [we serve] families and individuals facing the most challenging intellectual and developmental disabilities...When incidents inevitably occur, we strive to address them responsibly.”

This is probably a good time to warn you that some of the incidents we’re going to talk about happening at Carlton Palms are really disturbing. Instance after instance of violence against disabled people. If you’re especially troubled by that, you may want to sit this one out.

When I visited Arnaldo at Carlton Palms, the staff seemed nice. Didn’t seem super engaged with the clients, but they were friendly to Gladys and Miriam.

But I had seen the way Arnaldo’s unit supervisor gripped him by his waistband, looked him in the eye told him, “Be good!” when we took Arnaldo off to the chapel. Like it was a threat.

Miriam and Gladys asked me not to tell current staff I was reporting on Arnaldo while he was still in their care, didn’t want to risk his safety, so I looked for ex-employees. Found them by getting to know locals, and through sending private messages on LinkedIn. Two ex-employees would go on record, four others talked after I promised to protect their identities, because they still work in the industry or are just too scared of being sued by Carlton Palms.

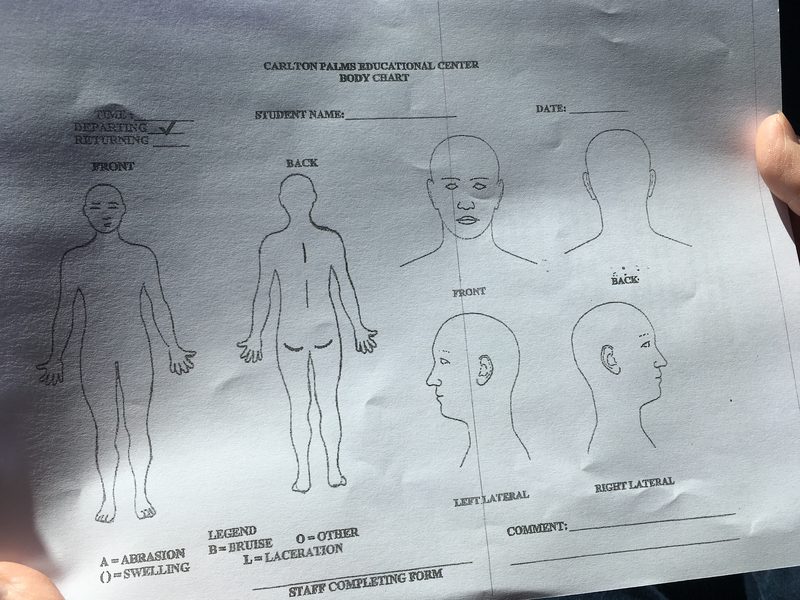

And there was also paper-trail to backup their stories — hundreds of pages of documents I received through public records requests.

What this all added up to about Carlton Palms was bad, deathly so. But what I also found out, is how many people have known this, for a long time. People that had the power to do something about it. And didn’t.

Arnaldo came to Carlton Palms in August 2016. After the shooting with Charles Kinsey and 35 days in the psych ward waiting for a place that would take him. And it had seemed like the only option, the only opening in a place licensed to work with people with needs like his.

People with needs like Arnaldo’s, people with developmental disabilities and “problem behaviors,” — if they get residential placement in Florida, almost thirty percent of them go to Carlton Palms. It gets more taxpayer dollars per person than any other facility in Florida. And instead of housing a handful of people like a group home, it has at times held nearly 200.

But back to Julie Kupchik. She was the woman you heard at the beginning...one of the former employees I found who was willing to be recorded.

JK: That was an eye-opener, that was a shocker. I just know that I couldn’t be a part of it.

Julie had been a classroom aide with autistic kids in Connecticut, doing a common kind of autism therapy, called ABA. When her husband’s job moved to outside Orlando in 2008, she got excited when she saw the Help Wanted ad for nearby Carlton Palms.

JK: So I thought Oh my god, this is gonna be perfect for me.

She started training right away, in a classroom with about six other recruits. Pay was just over ten dollars an hour, which might not sound like a lot but was pretty good money for Julie. The campus was beautiful.

JK: It was very interesting though because I felt kind of like a mouse in a cage where they would feed you just a little bit of cheese. Get you to do something and then feed you a little bit more of cheese but you weren't getting the whole picture but you knew you were missing something. It was just, it was very odd.

And then at the end of the training program, the instructor brought out a three ring black binder.

JK: It was, it was thick. It was big. And when you opened it up, this is where the reality came into play of — this was more than just dealing with children with autism.

Every single resident of Carlton Palms was in that binder. Julie took it home with her, read it multiple times. It included the very worst thing every client had done, written up like a criminal record. Cases of pedophilia, sexual assault, extreme violence. Employees would refer to these histories as lists of clients’ “crimes.”

They said the training set you up with the idea that clients would be very, very dangerous. It made me wonder what that binder says about Arnaldo?

And between you and me, I — I cried. I — I really thought long and hard about — I don’t know if this is gonna be the place for me or not. I don’t know if I can handle this.

But she decided to go for it. When she started, she worked the second shift. Two pm to ten pm. With teen boys.

JK: One thing that pissed me the hell off. There was no textbook or any sort of things to help communicate with them. That bothered me. It was just — honestly I felt like I was just sort of babysitting them until it was time for dinner.

The guys she watched over would spend the evening time in a central room with a few books, some balls. There was one guy who’d wash his hands repeatedly. Another guy who just rocked. Julie would sometimes read to him.

And this gets us to Arnaldo’s situation — what his therapist saw...where it looks like he’s not getting help with communication, not doing educational activities, basically just being left alone. That’s something other ex-workers also told me was pretty standard, so did a prior parent. What was more common, was just reacting. Address people’s behavior problems when they came up, forcefully, instead of taking the time to prevent flare-ups in the first place.

In the room where Julie worked with the teenagers, there was another client who would just pace. He was held in a waist chain. Just about all the time. They’d even strap him to his bed at night. All night.

JK: It was like a belt that was tied around his waist — and it had — like chain links that were attached to cuffs that went around his wrist. He could still move his arms but his hands would not be able to reach his mouth. At first I thought, ‘Holy shit, why is this kid in this belt?’ But when they explained that he had the particular disease of you know eating things anything everything to the point where he had been hospitalized because of his stomach and the issues you know it became more of a safety feature.

The young guy had Pica, it’s a serious eating disorder, a compulsion to put things that aren’t food in your mouth. It’s pretty common in institutionalized people. It can be treated with therapy. But instead, Julie said, Carlton Palms staff did what they do: physical restraints.

Restraints like the mask staff told Miriam that Arnaldo sometimes has to wear. Like the wrap mat his therapist saw employees hold him down on.

I learned that at Carlton Palms, most clients’ behavior plans include a blanket statement that allows staff to use of all kinds of available restraints. Reports show staff typically skip over the other steps — ways to calm someone down, give them space, try to communicate with them. They go right to the restraints.

A recent report cited one man who spent two-hundred and five minutes in a waist belt — even though he remained calm the entire time.

Another client was held down on a wrap mat, with wrist restraints, after the client tried to reach a telephone. To call the abuse hotline…

That young man Julie would see pacing, they just kept him in the waist chains all day, to keep him from putting things in his mouth. She had to keep an eye on the clock, had a spreadsheet where she’d check off preset intervals when she took one of his arms out of the chain for a few minutes at a time. Sometimes she’d let him out a little longer.

JK: One day in particular, I went in, and to my surprise, a TV had been brought into a room. And I thought, ‘Okay, well this is cool.’ He seemed a little bit — agitated that day. ‘Children do not like change. It’s new. What is this?’ I let his arm out and he just seemed very more — he was more hyper than normal. So I wasn’t going to extend the time I just kept it at the regular time and then went to put him back in it and he wasn’t having it. He picked the television up and he smashed it on my head.

AQ: Oh wow.

JK: Yeah.

I talked to another employee who had to run from a client who threatened her with a shovel. That same employee on another occasion was hit so badly she got a concussion. I heard of employees with broken bones, another who described staff injuries as, “Just routine.” I don’t want to minimize what these employees were dealing with — getting physically attacked at work, expecting to get attacked at work will take a toll on you. And in this setting, you then had to go back and serve your attacker dinner that night. It’s exhausting work, for eight, nine, ten dollars an hour. But by not getting trained to calm clients down, the staff at Carlton Palms seemed set up to fail.

In talking with former staff, I picked up on what seemed like a prison guard mentality: You gotta do what you can to keep residents down, or else they’ll take advantage of you.

But the thing you have to understand is the power difference between staff and clients. As a disabled person at Carlton Palms, yes, you can rebel. You can act out. Get violent. But the people watching over hold your entire life in their hands. Will you go outside today? Or be tied to a chair? What drugs will you take? Will you get to eat? Drink water? What time will you go to bed?

Another ex-employee who was willing to go on record is Emelia Andrews. She’s now an autism therapist in the Czech Republic. Halfway around the world. So she said, "Yeah, sure, I’ll talk." Had one memory in particular she wanted to share.

AQ: Will you set the scene?

Emelia Andrews: Yeah. There was a room called the solarium and it's just where the kids spend their time before going to bed or whatever.

I’d reached her over Skype. She also worked at Carlton Palms in 2008…

EA: And I remember being assigned to the solarium and just standing there and it was the shift change and I distinctly remember leaning against the wall and some guy came in and he was just in a really pissed off mood and he's like, "Man, I'm in such a bad mood I just want to mat somebody."

Mat somebody. As in wrap mat — strap someone down in a foam body pad. Saying you want to mat somebody is coming into work and saying I can’t wait to take somebody out. And Emelia says it gets at how permissive Carlton Palms was.

But what she said bothered her the most, why she ultimately left, was she didn’t feel like she was helping people…helping them to transition to somewhere less restrictive.

EA: I never felt like we were making measurable progress towards anybody transitioning out to a different place.

Because to Carlton Palms, graduating clients means letting money literally walk out the door.

One ex-employee said she saw more senior staff members intentionally provoke clients who were on their way out. Do stuff to cause meltdowns, to show they couldn’t leave…that they needed to stay there.

Another prior employee told me she’d see staff members provoke clients just to be petty, to make it so they wouldn’t get to go on fieldtrips, get meal privileges. No one I talked to ever saw a client actually transition out of Carlton Palms because they were doing better.

Why would families choose this? Do they even know? That’s next when Aftereffect continues.

Miriam and Gladys have heard rumors about Carlton Palms, have their own hesitations, but they told me they didn’t even want to read articles about what had happened there until Arnaldo was out. Didn’t want to feel even more guilty about him being in there.

How do other parents deal with this?

I got a list of current and past parents at Carlton Palms from another mother.

Denise Cosco brought her son Gene to Carlton Palms in 2007, when Gene was a teenager. Gene’s autistic, he’d had issues with aggression, had been kicked out of other group homes. Growing up, his mom Denise would call 911 on him several times a month, she’d get scared he was about to hurt himself, or her.

Denise Cosco: He started out with intense behaviors, of destruction of property, physical aggression.

Gene spent more than ten years at Carlton Palms. Denise can’t say enough good things about it. Just like Gladys with Arnaldo, Denise couldn’t see Gene’s bedroom…even though it’s against state policy. She didn’t like that but says Carlton Palms did right by her and Gene. He got less aggressive, more independent while there. He’d participate in work crews, different training programs. He now lives in a less restrictive group home.

Gene Cosco: It was nice. I used to go on the work crews and stuff.

Gene’s now 29. He left Carlton Palms in February 2017.

AQ: What was your favorite thing at Carlton Palms?

GC: Working on plaques and screwing the stuff and gluing like parts onto like plaques.

AQ: Did you like it there?

GC: Yes I did. I liked it a lot. I liked being there.

Denise prides herself on being on top of whatever services Gene’s getting. Gene’s a lot more verbal than Arnaldo, so he can tell her what’s going on, what was done to him. Denise has even sued people she thought weren’t treating Gene right. And she reads about the incidents of abuse at Carlton Palms.

DC: But there’s always stories that felt exaggerated. Who knows what really happened. Nothing can justify it. But who knows what really happened. I always try to see the other side and my experience was a positive one.

And she says she’d happily put Gene back in Carlton Palms’ care.

Catherine Kruger is another Carlton Palms mom. Her Jesse arrived seven years ago, he’s now twenty. Still lives there.

Catherine Kruger: We were very ignorant of what was available in the state when we came down here so we went on the recommendation of the APD.

That’s Florida’s Agency for Persons with Disabilities. Jesse’s also autistic, was having violent behaviors, issues with sexual aggression. The family had just moved from Pennsylvania, they had five other kids at home.

CK: And their referral was, that was the closest one that provided some of the services we felt he needed.

AQ: And when he first started, how did you feel about Carlton Palms?

CK: Just taking him over there was absolutely heartbreaking. He cried, we cried, he promised to be good. It was horrendous. Absolutely horrendous.

Catherine’s family lives even farther away from Carlton Palms than Gladys and Miriam, about an hour and a half. Only get to see Jesse every other week for two or three hours.

Catherine says when he got to Carlton Palms his behaviors got worse. And then he was sexually assaulted by another client. Staff had been in the room, apparently not watching. Carlton Palms called her and her husband to let them know it had happened, and that it was “dealt with.” Catherine looked into taking Jesse home, but child protective services said they’d take her five other children away if she brought Jesse back, said he was a danger to the other siblings. Catherine’s been closely following the news, the abuse reports at Carlton Palms. She’s looked for other options but at this point, hasn’t found another program that’ll take Jesse.

CK: He calls here every once in a while and he’s crying. He feels like a prisoner. He feels like he’s trapped, “Please, please, please let me come home, I’ll behave, I will — sorry.”

AQ: Yeah, Jesse calls home and asks to come home?

CK: Mm-hm. “I’ll be good, I won’t hurt anybody, I won’t do anything wrong, I can get a job.” Yeah. So he knows something is going on but I don’t think he’s aware of exactly what is going on.

Catherine says Jesse has seemed better in recent years, that his progress reports show that…but that Carlton Palms still isn’t letting him go.

CK: They give like a synopsis of the month and his sexual behaviors or his sexual aggression has diminished, his physical aggression has diminished, his self-abuse has diminished. He’s down to where I would say he’s dealable. But at the bottom it says, considering Jesse’s behaviors, he’s not ready yet for transition.

AQ: Huh, it doesn’t add up.

CK: No, and we have every one of those monthly reports since he went in there. We saved every single one of them.

AQ: What do you think’s going on?

CK: I have no idea. I have no idea.

AQ: how are you doing?

Shain Neumeier: I’m — I’m doing all right for — you know — insomnia and all.

Shain Neumeier is an attorney in Western Massachusetts. Also autistic, pronouns they/them.

Shain had stayed up late the night before we talked reviewing Carlton Palms records…ended up not being able to sleep.

SN: The part that for me really stands out as intolerable and disgusting is how state agencies — agencies such as the Florida Agency for People with Disabilities is completely unwilling to take a hard stance and really shut down this program — after years and decades of abuse. In doing so, they’re complicit in the abuse and in fact they’re legitimizing it.

Shain’s set up a law practice with the specific goal of shutting down places like Carlton Palms. Shain’s one of the most prominent advocates in the country against restrictive facilities. They say there’s places like Carlton Palms all across the country.

AQ: How’s this still a thing?

SN: A lot of it is out of sight, out of mind. Carlton Palms and many other facilities are — are located in remote areas. Often miles away from a town — sometimes deliberately to make escape harder for residents. And a lot of things happen when there’s no one around to watch them.

Between 2001 and late 2014, Florida’s Department of Children and Families carried out 148 abuse and neglect investigations at Carlton Palms. It’s up to Florida’s APD to react to those investigations.

We went back and forth with APD over months, while they decided whether to grant me an interview. Ultimately said no. Issued a three paragraph statement saying “APD’s number one goal is to do all we can to thoroughly serve the needs of Floridians with Developmental Disabilities.”

In 2011, the agency started writing up administrative complaints against Carlton Palms. First they requested a three thousand dollar fine for four counts of abuse against clients by employees. A resident kicked in the ribcage by a staff member. One lacerated with plastic by a staff member. Another hit so hard their tooth fell out. And a fourth resident punched in the chest by the person charged to care for them.

All for three thousand dollars in fines...This is a facility that receives over 20 million dollars a year in Medicaid funding. But then, instead of the fine, the agency settled for increased employee training at Carlton Palms.

SN: If I never hear another agency saying, “Training your staff is the solution for abuse,” it will still be too soon. These states are unwilling to crack down on these facilities both because of public perception of these schools and because they don’t wanna deal with the litigation or other — hurdles to closing them.

In 2012, the Agency had to write up another administrative complaint. Explicitly detailing four more just as disturbing counts of bodily harm done to Carlton Palms clients at the hands of staff. And this time APD looked serious. They asked for Carlton Palms to stop taking clients. For a year. But just two months later, the agency settled instead for more video surveillance at the facility. And went right back to sending clients there. They didn’t have a lot of options.

We made some phone calls. And discovered that the company Carlton Palms contracted to do this video surveillance, surveillance to keep them accountable, is a company operated by Carlton Palms’ founder, a man named Ken Mazik.

SN: There’s also — concerns about preservation of evidence. “Oops — we accidentally deleted that footage you asked for, state. How did that happen?"

The reason Shain’s brought up the deleted video footage, that’s from something that happened in 2013.

Paige Lunsford was a 14-year-old non-speaking autistic girl. She’d been throwing up for five days. On the fifth night, she threw up nearly 30 times. A staff member suspected she was doing it on purpose. So they tied her to a chair. By her wrists, arms, ankles, and waist. She died later that night. Of dehydration. Video of the incident was “accidentally deleted,” according to Carlton Palms administrators.

Again, the video surveillance is run by a company headed by Carlton Palms founder.

In 2015, ProPublica did an investigation into Carlton Palms. Pointed out another suspicious client death in the nineties. Brought all these accounts of abuse, the lack of action by the state, all into the light. Carlton Palms swore they’d do better. The state agency promised more oversight.

But what’s happened since then? I submitted a freedom of information request to track the progress. Carlton Palms had racked up at least 148 investigations into abuse and neglect in the 14 years leading up 2015. In the next three years? There were 149 more.

In 2016, the state of Florida made an agreement with Carlton Palms to stop admitting new clients...This was two months before Arnaldo arrived...and to close by March 2019. A few members of the Florida legislature have tried to pass bills to make sure this happens, but they keep getting defeated. Apparently thanks to parent advocates. Who don’t want to see Carlton Palms closed.

SN: They bring out their core group of parents who say this saved my life, the phrase or variations on it — “My child would be in prison or dead.” Some variation on that.

AQ: I mean are those responses not real though when parents say, like, “I don’t know what I would do with my child if Carlton Palms didn’t exist?”

SN: It’s in good faith on the part of the parents. It’s often out of fear based on what they’ve been told by schools, by the state agencies, “Oh, we don’t have another placement for this person or we don’t have the staff to help them in homes.”

The problem for APD — closing Carlton Palms means having to find other places for the over one hundred people still there. And you saw how long it took for Arnaldo to get into Carlton Palms after the shooting. These services are hard to come by in Florida. In a lot of states.

SN: The problem is, for the things that people consider a problem, is it requires a big up-front investment. It requires dismantling the current system or most of it and building something entirely different that looks like something we’ve not really seen ever.

Actual real community services. But that kind of dismantling takes a lot of money. In a state where disability funding is already stretched painfully thin. It’s cheaper to stick with what you know.

I’d set out this episode to figure out what’s happening behind closed doors at Carlton Palms. And I got answers. Count after count of abuse, a state hesitant to do anything about it.

Arnaldo has not suffered physically in the worst ways some clients have at Carlton Palms, as far as I know. But he’s still a victim of the same circumstances. A state disability system starved for resources. A facility taking in millions but pinching every penny possible. By overworking, under-supervising, underpaying their staff, who can take out their aggression on clients. Clients who don’t have a whole lot of other options, if any.

And it can seem like there’s no winning here. But there is one person who’s made a fortune off Carlton Palms. The facility’s elusive founder. He doesn’t give interviews. Rarely gets his picture taken, accounts of his wealth are the stuff of local legend.

It’s no accident Carlton Palms has the power it does in the state of Florida. This was actually a carefully orchestrated plan. By this one man, Ken Mazik, who had money and influence, and knew how to use them.

On the next episode of Aftereffect, the man who made Carlton Palms what it is. And how his current business dealings, help explain how this place came to exist, and may never go away.

Aftereffect by Only Human is a podcast from WNYC Studios.

Aftereffect is reported by me, Audrey Quinn, and edited by Ben Adair. Additional reporting from Aneri Pattani. Production help from Phoebe Wang.

Cayce Means is our technical director with engineering help from Matt Boynton and Jared Paul.

Hannis Brown is our composer.

Our team of talented reporter-producers includes Christopher Johnson, Mary Harris, Amanda Aronczyk, and Christopher Werth. With help from Margot Slade.

Michelle Harris is our fact checker. Our interns are Kaitlin Sullivan and Nicolle Galteland.

Jim Schachter is WNYC’s Vice President for News.

Support for WNYC’s health coverage is provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and Science Sandbox, an initiative of the Simons Foundation.

Thanks also to the Rosalynn Carter Fellowship for Mental Health Journalism.