The Drug War

( Neal Ulevich / Associated Press )

Speaker 1: Listener-supported, WNYC Studios.

Kai Wright: Last summer, as the presidential election heated up, we decided to spend some time hanging out with Donald Trump supporters in Suffolk County, Long Island. We expected to hear a lot of anxieties, economics, terrorism, immigration, and demographics, but here's something that caught us off guard.

Speaker 3: I messaged one of my old friends on Facebook the other night just to have a conversation with her, and I was like, "Oh, how's everything been?" She was like, "My brother overdosed." So there's a whole lot of overdosing going on around here.

Kai Wright: Suffolk County leads New York state in drug overdoses by a lot, not The Bronx, not hipster Brooklyn, but the suburbs of Long Island. In recent years, this has been true in white suburban and rural communities all over the country. It started with the overprescription of pills, it spiraled into cheaper and more affordable heroin, and now has grown into the drug fentanyl, which people mix with heroin, and researchers say it is the real reason opioid overdoses have reached historic highs.

Kai Wright: So now a lot of folks are finally taking real notice of this epidemic and asking what can be done to stop this crisis, which for other people is kind of frustrating.

Joe Turner: It's always been an epidemic, but it was an epidemic in the Black and Latino communities.

Kai Wright: This is Joe Turner. He's touring us around the halls of an addiction treatment center called Exponents in Lower Manhattan.

Joe Turner: We had 14-year-olds, 15-year-olds, dying in overdoses in tenement stairways, silence. But once it got into the suburbs and hit what is so-called middle America, then the alarm went out.

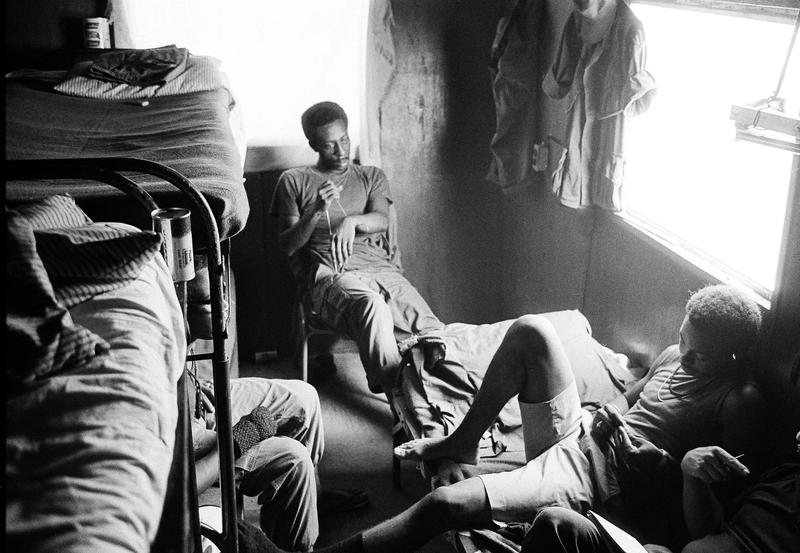

Kai Wright: Exponents started counseling people with opioid addiction in the late 1980s. Turner points to a photo of about seven men standing in a church basement on the Lower East Side of Manhattan not long after they'd left prison.

Joe Turner: These are the first graduates in 1988. Unfortunately, AIDS took no prisoners, so none of them are around today.

Kai Wright: It's an aging snapshot of a part of the mobilization against AIDS that doesn't get quite as much attention as the culture war over sexuality. They were pioneering a public health strategy called harm reduction, which basically means meeting people where they're at.

Joe Turner: Most of the programs had the rule that you could not get high that day, which really made no sense since an addict is in the business of getting high every day. So we said, look, dead addicts don't recover. So our lessons go way back on how to engage individuals successfully.

Kai Wright: The obvious question then is, why can't we just build on those lessons now? Why does it feel like we're starting from zero in dealing with today's raging epidemic?

Kai Wright: I'm Kai Wright. This is The United States of Anxiety: Culture Wars, and in this episode, we will try to answer those questions.

Crowd: USA, USA! Yes, we can! Yes, we can!

Kai Wright: We are taking another trip back to the Nixon era, another time when an opioid crisis was shaping national politics, mostly because of crime, and the federal government's response then both set up the successes Joe Turner found decades later and baked in the failures we are still trying to get past today. Reporter Christopher Johnson tells the story.

Crowd: [inaudible 00:03:49]

Nixon: Mr. Chairman...

Christopher J: Richard Nixon must've been savoring all of this.

Nixon: ... Delegates to this convention.

Christopher J: August 1968, Miami Beach, the RNC convention. He's at the podium.

Nixon: My fellow Americans.

Christopher J: Nixon had spent half the year beating back two popular Republican governors for the nomination, Reagan and Rockefeller. He'd already made one go at the presidency eight years earlier, barely losing to John F. Kennedy. It was finally his time.

Nixon: Tonight, I again proudly accept that nomination for president of the United States.

Nixon: But I have news for you. This time there's a difference, this time we're going to win.

Christopher J: Jump forward to late January 1969. Nixon is sworn in as the first Republican president in eight years.

Nixon: And riders on the Earth together, let us go forward firm in our faith, steadfast in our purpose, cautious of the dangers, but sustained by our confidence in the will of God and the promise of man.

Christopher J: He's got a problem though. Nixon knew that crime was on the rise. He promised a robust domestic battle that was going to shut down the chaos. He was also fiercely political with one eye already looking towards his '72 reelection. So Nixon couldn't not deliver, but Evan Thomas says the new commander in chief was preoccupied.

Evan Thomas: Nixon's primary concern was foreign policy, US-Soviet relations, Chinese relations, the war in Vietnam. The domestic concerns were much less important to him. He saw them primarily as political, as a way to get elected, but not something that you spend a whole of time on and he was not wrong.

Christopher J: Fortunately, he already had a deep bench of domestic policy experts. These guys were ready to start going live with the new conservative, get-tough agenda. It was a tight fraternity that included in Nixon's Advisor John Ehrlichman and his deputy Bud Krogh, Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman and Attorney General John Mitchell. Before many of these guys became famous as the Watergate masterminds, they helped engineer one of Richard Nixon's signature initiatives, the War on Drugs. Soon after the inauguration, this happened.

Dan Baum: There was a moment that took place in John Mitchell's office. He was the attorney general.

Crowd: Dan Baum is a journalist and historian. In his book Smoke and Mirrors about the war on drugs, he writes about this meeting in Washington. He spoke to some of the guys who were there in the room in Mitchell's office.

Dan Baum: And he's saying, all right, people, we won this election on a law and order platform. We are the Justice Department. How are we going to make the federal government a visible player in law enforcement? I want to hear how we're going to get our people on television making the country safer, restoring law and order.

Christopher J: They kick around a bunch of ideas. Mitchell shoots them all down.

Dan Baum: And then somebody says, what about drugs? They're imported. Right there, we've got jurisdiction and we can claim that we need to chase the illegally imported products into the smallest towns in America if we need to to track them down. And Mitchell says, I like that.

Christopher J: And there it was. What about drugs? Now drug enforcement had already been gaining momentum as a federal issue. President Johnson merged the powers of law enforcement and drug regulation into a whole new acronym, BNDD. Side note, this Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, in the next decade Nixon would transform it into the DEA.

Christopher J: Now today when we think of how America has dealt with its drug problems over the last half century, we're familiar with a blustery law enforcement-heavy approach. That's why what happens next is kind of strange. The Nixon White House starts to invest in drug treatment.

Dr. DuPont: Now, how did that happen? So your question is... I'm going to tell you how it happened. I can tell you how that happened. He did not come to that easily, let me tell you.

Christopher J: At the same time, Nixon's team was looking for ways to bring crime down as quickly as possible. Dr. Robert DuPont was working as a psychiatrist in a DC correction system. He'd been counseling inmates when he noticed a pattern. He put together a research team and discovered that nearly half of the 200 men they interviewed said they were heroin users.

Christopher J: DuPont felt he'd found a strong connection between crime, mostly low level stuff like burglary and purse snatching, and drug abuse, especially heroin abuse. He heard about a new treatment program. It included this drug the Germans developed during World War II to manage pain when opium was in short supply, it was called methadone. He asked the city for seven and a half million dollars and use it to set up the city's first methadone clinics.

Dr. DuPont: Within two months we had 2000 people in treatment and it became very large. Over the next three years, we treated 15,000 heroin addicts in Washington mostly, but not only with methadone and the crime rate went down. The overdose death rate went down and it was a public health triumph really. It demonstrated that a health intervention could make a difference in a community-wide problem of heroin addiction.

Christopher J: It didn't take the White House three years to notice DuPont's work. A few months after the clinic opened in 1970, Bud Krogh, part of Nixon's domestic team, got a batch of rough FBI figures. Crime in this city was already dropping.

Dr. DuPont: Krogh was a brilliant person and he just wanted to get the job done, but he carried this message to Richard Nixon and Richard Nixon was a desperate dude. He needed to do something.

Christopher J: 1970, Nixon's been in the White House for a year. Before anyone knows it, it's going to be campaign season again. He's calling Bud Krogh and he is impatient. Where are my slam dunks? Krogh sets up a gamble. Inspired by what he'd seen DuPont pull off in DC, Krogh tells his aide to find the best methadone treatment program in the country, something they can copy and make it national.

Kai Wright: Which brings us to this guy, a psychiatrist, an educator, a leader in addiction research, the man who helped pioneer a national methadone treatment program and who would become the country's first ever drug czar, Jerome Jaffe. Christopher got him on the phone and asked, what's he up to now.

Jerome Jaffe: I'm sitting here waiting to have dinner.

Kai Wright: We'll meet him after the break.

Kai Wright: I'm Kai Wright. This is the United States of Anxiety and Christopher Johnson is walking us through Nixon's response to that era's opioid crisis.

Christopher J: At this point, it's 1970. Richard Nixon is just a year into his presidency, but his team is already shaping two very different approaches to the drug issue and they're developing side by side, drug enforcement and drug treatment. Dr. Jerome Jaffe had built a successful methadone program treating mostly black men in their 30s on Chicago's South Side. That program did so well, he was asked to take it statewide and that's where Nixon's people found him.

Jerome Jaffe: I was called by the White House staff sometime, I guess, in June of 1970 to talk about what we were doing when I was the head of the treatment program in Illinois, and I was asked to write a kind of a brief or white paper to be submitted to the president and to gather together some experts. Frankly, we were given very little time to do it and we proposed a significant expansion of treatment and research.

Christopher J: Jaffe saw the Nixon was taking more and more of a law and order approach to dealing with addiction. Cut it out, Jaffe's report said. Law and order might've been what won the election, but a drug program required counseling, care and yeah, when it came to heroin, it might take methadone maintenance. So he submitted his report and went back to work. There we were, summer of 1970, on the very edge of getting a national treatment program and then...

Jerome Jaffe: Not much happened.

Christopher J: Nixon's guys had done exactly what they were told to do. They found the best guy to design a program that could help thousands of men and women hooked on heroin and other drugs, but as eager as the administration was to show it was fixing drugs and crime, there was still skepticism about methadone's effectiveness.

Christopher J: Meanwhile, Elvis shows up at the White House unannounced with a handwritten note vowing to help with the drug fight. Elvis shakes, Nixon's hand gives the president a Colt 45 pistol and trash talks The Beatles. He then requests and is given a special federal agent's badge from the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. He hugs Nixon and splits. The King's war on drugs never happened. His own death in 1977 is reported to be drug related.

Christopher J: Anyway, it's now spring 1971, almost a year since the White House first contacted Dr. Jaffe and all he'd really received for his report was a thank you note from the President. So then, well let me read you this headline from the New York Times, May, 16th, 1971: GI Heroin Addiction Epidemic in Vietnam.

Christopher J: A couple of Congressman had just come back from South Vietnam where they were checking out reports of rampant heroin use among US troops. They'd found out that one in 10 GIS was addicted. In some places, one out of four troops was hooked on dope. What was especially troubling for the administration was Nixon had already started to draw down, as many as 60,000 men hooked on heroin now heading home. Big problems says Michael Massing, who wrote The Fix, a book about the Nixon administration's drug policy.

Michael Massing: There were two aspects to Nixon's concern with drugs. One is drug use in Vietnam among GIs there and there was great fear that they would come back to America with their knowledge of weapons and a warfare and whatnot would wreck havoc in our cities and so that became a great preoccupation once he was in office.

Michael Massing: Early on, there was also the problem of crime. You had large scale heroin addiction and abuse in our cities and that was very much seen as linked to crime. So, the crime issue is something that politically could be taken advantage of.

Christopher J: America now had a drug issue on two continents. For Nixon's staff, this was also an opportunity.

Michael Massing: When they saw this problem of both crime linked to heroin use as well as soldiers in Vietnam who were doing heroin, the two sort of became merged and they looked around for ways of getting quick results on this, because they were already very early on looking toward reelection campaign and so how could they get quick results?

Christopher J: Things started moving fast. After a long radio silence, Nixon's team calls up to Jerome Jaffe at the end of May 1971. He flies out to DC a few times over just a couple of weeks, first to map out a plan for the GI epidemic and then on June 17th, just a month after that New York Times piece on GIs and heroin, Jaffe is whisked from the airport to the White House Cabinet Room. The president is there, so are the TV news cameras and the reporters. Jaffe had no idea what was about to happen.

Nixon: You want to join me here? Won't you be seated please, ladies and gentlemen.

Christopher J: With glasses and sideburns slicing down to his jaw, Jaffe gets invited by Nixon to stand to his left onstage with the rest of the President's inner circle.

Nixon: Come on, Dr. Jaffe, and Mr. Krogh, Mr. [inaudible 00:16:25], all right, all right.

Christopher J: Nixon opens by mentioning a meeting he's just had with lawmakers. What he was about to tell the country would be the culmination of all that work his team had done developing both its law enforcement and its treatment-based approaches to drugs. Nixon was synthesizing it into a well funded federal mandate. For the first time in US history, a president was formally declaring the War on Drugs.

Nixon: I began the meeting by making this statement, which I think needs to be made to the nation: America's public enemy number one in the United States is drug abuse. In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive.

Christopher J: Nixon was pledging to merge each of the federal government's drug programs, foreign and domestic, treatment and enforcement, into one agency. He wanted to commit a total of $350 million to the effort. More if necessary, and here America is the man who's going to head it.

Nixon: Dr. Jaffe, who will be one of the briefers here today, will be the man directly responsible. He will report directly to me.

Christopher J: Jaffe says he found out about the new gig on his way over to the press conference. He hadn't packed an overnight bag and definitely didn't have anything to wear on TV.

Jerome Jaffe: Well, the first thing I did is send somebody out to buy me a shirt. It was a size too big. There are pictures, you can see it. You want to know the next thing I did?

Christopher J: Yes.

Jerome Jaffe: Well, the next thing I did, I think, was to walk out in front of the press corps and have Nixon announced that I was going to take on the problem and then not having thought that anything was happening except that my shirt was too big, I was in left to answer the questions of the press corps.

Nixon: The briefing team will now be ready to answer any questions on the technical details of the program.

Christopher J: And how did you do?

Jerome Jaffe: I don't know. You can imagine how you would do under those circumstances. Nobody asked me anything about the pharmacokinetics of heroin.

Christopher J: Dr. Jerome Jaffe was now head of the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention, the SAODAP. They called it [say-oh-dap 00:18:41]. He'd been drafted as the nation's first ever drug czar. Jaffe's first job was to head to Vietnam, where he set up a urinalysis system and took to weaning troops off a dope. Operation Golden flow, they called it and it worked.

Christopher J: Back home, SAODAP built a national drug treatment and prevention program that included counseling and sometimes even job placement. Waiting lists in cities across the country were bulging with people seeking methadone treatment. Jaffe's team hustled to meet the demand. Crime fell off in dozens of cities, credited at least in part to the availability of treatment. But Michael Massing says Nixon had another problem. He couldn't get away from.

Michael Massing: Nixon being the canny politician that he was saw where the public sentiment was, and even though crime was going down, drug overdoses were going down, there was still a very large degree amount of concern in the population about crime, about guns, about the inner cities and so on and so forth. And it was there to be exploited.

Christopher J: The impatience with crime and drugs and disorder that helps sweep Nixon into the White House, it hadn't subsided. Polls going back to early 1971 indicated Americans wanted a show of force.

Michael Massing: It's a shame. It's a shame because they had really come up with a strategy that was both more humane and more effective and yet it seemed to go by the boards.

Christopher J: At the very same time, Dr. Jerome Jaffe is developing a national drug treatment program. Nixon's domestic team is building out their drug enforcement project. The image that we have today of the zero tolerance War on Drugs. This is where it's really taking shape. In his book Rise of the Warrior Cop, investigative journalist Radley Balko describes a White House driven PR blitz designed to tie heroin to crime in the public imagination. Not long after Nixon declares drugs "public enemy number one," he sends his customs chief to head a new agency called the Office of Drug Abuse Law Enforcement or ODALE.

Elizabeth H: ODALE was, as Nixon officials called it, this kind of cadre of presidential drug cops. This was essentially targeted anti-drug law enforcement outfit that was run directly out of the White House and it came very close to crossing constitutional lines about federal police forces.

Christopher J: Harvard History Professor Elizabeth Hinton writes about ODALE in her book From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime.

Elizabeth H: The idea was to attack kind of the supply side of narcotics trafficking and to get the big kingpins and the big drug pushers. But in the end in practice, when these federal agents are kind of unleashed and targeted Black urban neighborhoods, they're really kind of going after low level drug dealers and drug abusers. And so you begin to have these kind of raids on people who are thought to be drug dealers but also kind of stop and frisk arrests on a frequent basis.

Christopher J: This was the feds working with local cops, drawing guns and kicking in doors. That Blitzkrieg was done largely for the news cameras that had been told ahead of time to show up. ODALE only lasted 13 months, but agents managed to pull off more than 1400 raids, many of them botched and marginally constitutional.

Elizabeth H: When ODALE was exposed, then the program disbanded and Nixon eventually kind of dissolves its responsibilities into the DEA.

Christopher J: The DEA, the Drug Enforcement Administration. This was 1973, President Richard Nixon wasn't long for that office and then he has to watch as Rockefeller, the guy he'd bested for the Republican nomination just five years earlier, one ups the president's zero tolerance rhetoric. The liberal New York governor was beginning to roll out a set of draconian punishment-heavy drug laws that would come to bear his name.

Michael Massing: The Nixon people saw this and they wanted to get out ahead of this. They were sensitive to what Rockefeller was doing and sort of didn't want to be left behind.

Christopher J: Now there's one more glaring piece to Nixon's battle with heroin, marijuana and other narcotics. The War on Drugs as a cold, calculated racialized political tool. Nixon's top domestic policy guy, John Ehrlichman, has copped to exactly this strategy. Nearly two decades after he went to prison for his role in the Watergate scandal, Ehrlichman talked to Dan Baum, who was working on a book about the war on drugs.

Dan Baum: And he told me the '68 campaign and the Nixon White House had two political enemies, black people and the anti-war left. And we needed a way to destabilize both those communities, to demonize them on evening news, to arrest their leaders, to break up their meetings. And we figured that if we can associate Blacks with heroin and the hippies with marijuana, we could use drug enforcement and drug demonization to demonize these two communities.

Dan Baum: Now I've got to say, a lot of people have read that quote and said, you see, this is prima facie evidence that the Nixon administration was racist because they wanted to destabilize and screw up in jail and demonize Black people. But that is not at all what Ehrlichman is saying. Ehrlichman was an intensely political man and he was talking about those two communities as problems for the Nixon administration.

Dan Baum: Ehrlichman was right. Those communities were political problems for that White House, and they were looking for ways to fight back. That is not a cultural war and that is not prima facie evidence of racism. That is an intensely political White House waging political warfare.

Christopher J: But by the mid 1970s, historian Michael Massing says people were losing interest in the drug issue.

Michael Massing: There was so much else that was going on, oil crisis, the idea of maintaining the drug treatment network that had been set up under Nixon just wasn't as exciting, and so the I was taken off of it. And during the Ford-Carter years, it was like in a holding pattern. And then once Reagan got in, the whole idea of drug treatment lost favor. It was seen as coddling addicts. You needed the tough love approach, just say no, you should be able to get off.

Christopher J: There's been a lot of critique and lament over how the War on Drugs unfolded over the last 40 years or so. Under President Reagan, we saw an explosion of the US prison system. Men and women locked away for two and three decades, sometimes for life, on drug offenses. We've seen the violence of the street trade and the assault on those drug wars by Pentagon supply, militarized police. But one of the biggest victims of drug policy after Nixon has been treatment and it's a change Nixon himself may well have helped set in motion.

Michael Massing: From the second term of Nixon through Ford and Carter and then of course into Reagan, but ever since we have gotten away from making a public health approach the centerpiece of how we deal with drug abuse in America and the Rockefeller drug laws were in some ways the original sin on this that they became a model, and it was just insanity to use a mass incarceration as the way to deal with this problem.

Michael Massing: And we're now trying to fight our way out of it, and even with all we know now, the progress is very slow and nobody is looking at the question of how hard it is to get treatment in so many parts of the country, how hard it is to get rehabilitative services, to get methadone and other maintenance drugs that can help people. We could do such a better job in dealing with this if we realize what we once had and how we've gotten away from it.

Christopher J: What we once had, at least in a form of treatment, hasn't been without its controversies. Since methadone was first introduced in the 1960s in Black communities, protests had been fierce. Malcolm X, James Baldwin, and others said it was essentially substituting one form of addiction for another, that it was more an act of control than a gesture of care for Black Americans. Maia Szalavitz is a journalist who's written a lot about drug policy and addiction. She says the challenges with administering methadone have persisted over the decades.

Maia Szalavitz: It is the most regulated medicine in the American pharmacopia.

Christopher J: US drug law has methadone listed as a schedule two narcotic, that puts it in the same class as cocaine, meth, and fentanyl. The synthetic opioid at the center of our current overdose epidemic. Doctors can prescribe methadone for addiction, so the only way to get treatment is to go to a clinic but good luck finding one.

Christopher J: Methadone clinics have such bad reputations as places that draw addicts and crime, that residents put up fierce protests against them opening up in their backyards. So some of those places in America experiencing a new opioid problem can't get help. And even if you are on methadone maintenance, Maia Szalavitz says the experience can be frustrating.

Maia Szalavitz: People have to show up everyday to the clinic for at least the first 90 days and some states require it for much longer. You have to get urine tested all the time. It's very degrading in terms of that and they are pretty much chained to the clinic because if you go for more than 24 hours without it, you're going to have withdrawal. And if you're not allowed to take it home with you, then you're not going to really be able to travel.

Christopher J: It's been almost half a century since Richard Nixon put one of the leading authorities on opioid addiction at the head of our national drug program. Within just a couple of years, his agency succeeded in treating tens of thousands of heroin addicts, both in the US and those stationed in Southeast Asia. Today, we are waist deep in an unprecedented storm of opioid addiction and death.

Christopher J: The New York Times has estimated that as many as 65,000 people died last year from drug overdoses. Many of those were opioid related. 2017 is on track to be even worse. The heroin problem of the '60s and '70s was really different from our modern overdose crisis, but if we had a solution then could we use it now?

Kai Wright: Before we close this episode, we want to revisit our discussion about the fight for religious freedom. A couple episodes back, we hung out with culture warriors in Mississippi who were debating that state's law allowing religious exemptions from the growing body of law protecting LGBT people from discrimination. That's episode seven. Check it out if you missed it.

Kai Wright: Anyway, in the past couple of weeks, there has been a lot of news in this particular culture war. A federal appeals court has approved the Mississippi law that we discussed in that episode, the one that pastor Brandy Lynn has challenged in court. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court has decided to hear arguments for a case involving a Colorado bakery owner who refuse to sell a wedding cake to a same sex couple.

Kai Wright: And separately, it has ruled that the state of Missouri must provide public funds to fix a church playground. This is the first time that government has been mandated to directly fund a place of worship. So in light of all this news, we thought we'd share a few voicemails we got from you in response to our episode. A listener named Matt told us he was raised Catholic, but when he started to get politically active in his teenage years, he found that his faith was in direct conflict with the citizen's rights he was fighting for today. He considers himself an atheist.

Matt: I feel that not only does religion itself harm our political process, but it harms us on a deeper level because it teachers of a better life after death, much less time is focused on being good to ourselves and to others while we are here but the time we know we have.

Speaker 1: Given his understanding of our political system, Matt worries that his family could pay for his own lack of religion.

Matt: I have lost sleep over the years with the knowledge that my free thinking children could be ostracized from the political process based on their non-religious point of view. Catholic, Lutheran, evangelical, Church of Christ, even Mormon, all are accepted and embraced for their point of view. Yet most of them hear the word atheist and immediately think of Satanism or something that came to that. So that's the world I live in.

Speaker 1: On the other hand, a listener named Marlon in Houston, Texas is a self identified conservative Christian and as such he says he has conservative views about things like sex and marriage and gender definitions and abortion. But he says that sometime while he was in college, he decided that just because he holds those beliefs, it doesn't mean that they should be the law of the land.

Marlon: I can believe if I or someone can believe that a Christian marriage as defined by God as we understand Him from the Christian Bible is between a man and a woman. But that's a terrible idea. It's enshrined in the civil law. Our law, the basis on the basis of our law is that that the government shall established no religion. So how can we go to one religion and say, let's define marriage with the religion says, and which religion, which denomination gets to speak for Christianity? What about those that have no religion?

Speaker 1: Marlon says that this logic can be applied to other political debates too, like abortion.

Marlon: If you have a problem with abortion because you believe that God starts life in the womb or with contraception because you believe that God ordained sex for procreation only, again, that's a religious view of a particular religion or particular school of thought in a particular religion or maybe it's shared by many religions. But again, in society we have to protect people of all different religions and no religions. So I don't think there has to be a conflict.

Marlon: I followed God's law, not because I'm afraid that I'm going to go to jail or be persecuted or prosecuted by my peers in my state, I followed God's law because I want to serve God. That's not the purpose of our civil criminal law. The purpose of our civil criminal law is our society works together and so that's how I reconcile those differences when they come up.

Kai Wright: Thanks to all of you who have been calling in and leaving messages for us. They really help. And if you'd like to keep adding your voice to the conversation, do call us up, (844) 745-TALK. That's (844) 745-8255 or you can tweet us using the hashtag US of anxiety.

Kai Wright: We've been talking to you for almost a year now since we began reporting this series last summer, and so in our next episode we'll take stock of what we've learned. After all, it'll coincide with the 4th of July, a time when many of us get together and barbecue and bake pies and drink rose and maybe fight about politics.

Speaker 17: If you're a Democrat and you look at a Republican, you know you're a bad person, you're the enemy.

Speaker 18: That is true. Republicans are rich, privileged, not caring for the people and "take my money and screw you" kind of people.

Kai Wright: That's next time. The United States of Anxiety: Culture Wars is a production of the narrative unit of WNYC News and WNYC Studios.

Kai Wright: Christopher Johnson reported this episode. You should also check out Christopher on the podcast of 100:1, The Crack Legacy. He's the host and co-producer of that series and you can find it wherever you get your podcasts starting July 10th.

Kai Wright: The narrative unit team includes Reniqua Allen, Rebecca Carroll, Paige Cowett, and Patricia Willens. Bill Moss mixed this episode, and our technical director is Cayce Means. Hannis Brown is our composer and our theme was performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band. Andy Lanset is our archivist. Our digital team is Lee Hill. Diane Jeanty and Jennifer Hsu. Jim Schachter is vice president of news for WNYC. Jessica Miller is the narrative unit's producer. Karen Frillmann is our editor and executive producer, and I'm Kai Wright. Talk to you next time.