Enshittification Part 3: On Saving The Internet

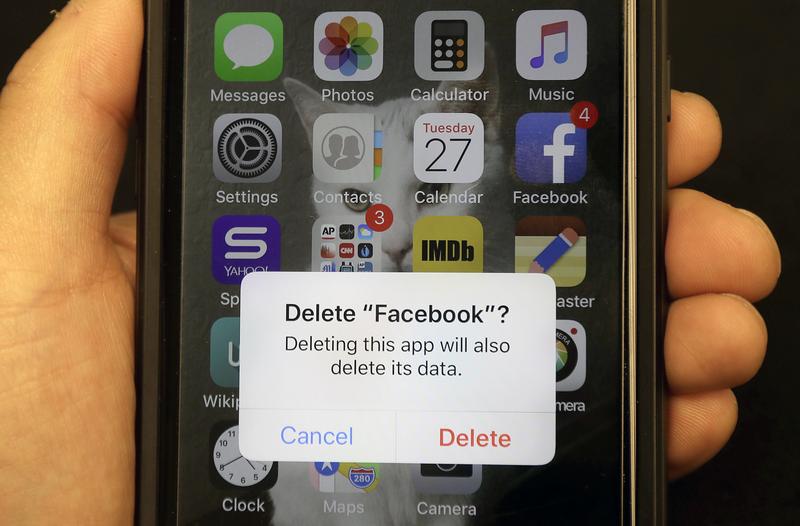

( Jeff Chiu / AP Photo )

This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone with the final part of my discussion with the great Cory Doctorow about the process whereby big platforms go bad. In this section, sometimes I'll be talking to Cory, sometimes to you to make it more concise because this is the solution section both uplifting and deeply problematic.

The problem, for instance, of passing common-sense regulation, which is hobbled by confusion over how the internet works, confusion abetted by platform designers and also by the fact that those designers are rich, and thus, effective lobbyists.

Cory: It's not that they're rich, it's that they're rich and united.

Brooke: A crucial distinction one only has to look back on the early days of this century.

Cory: Tech at the time was like 150 squabbling small and medium-sized companies that all hated each other's guts and were fighting like crazy. Lawmakers heard contradictory messages from tech. The consolidation of tech, that produced a common playbook. Now, we get a lot of tech laws that are very bad, that tech has pushed for because tech is able to sing with one voice.

Brooke: Congress offers bad solutions because they don't get the internet.

Male Speaker: The internet is not something that you just dump something on. It's not a big truck. It's a series of tubes.

Cory: You don't have to get the technology in-depth to be able to make good policy. The last time I checked, there weren't any microbiologists in Congress, and yet we're not all dead from drinking our tap water. What you need to be able to do is hold a hearing in which the truth emerges from a truth-seeking exercise where adversarial entities counter one another's claims and an expert regulator who isn't captured by industry is able to evaluate those claims. That's how you get good rules.

Brooke: Instead, we end up with regulations that are simply unworkable?

Cory: Since the 1990s, every couple of years, like a bad penny, someone proposes that we should make cryptography that works when criminals and foreign spies and stalkers are trying to break into it but doesn't work when police officers are trying to break into it.

Brooke: I'm not an expert. It sounds to me like, if you're going to try and create an encryption system that will protect you from crooks but not from each other, you're not going to get an encryption system.

Cory: Nailed it right there on the head in one. We have a name for what lawmakers do when we point this out, they say, "Nerd harder. We have so much confidence in your incredible genius as a sector. Surely, all you need to do is apply yourself." Sometimes they're right. Sometimes there's a dazzling act that goes on from tech where they say, "This is impossible," and what they mean is, we'd rather not do it. That would be things like, can you have a search engine that doesn't spy on you? They're like, "That's like having water that's not wet."

Brooke: Which brings us to the first of Doctorow's three prime solutions to en***fication, fixing the problem of user privacy. Platform designers say their services can't run without using our data. They rarely say how or why. Why not begin the fix by returning to a form of advertising we had two decades ago, ads based on context rather than behavior.

Cory: Let's start with how a behavioral ad works. You land on a web page, and there's a process where the web page, the publisher takes all the information they have about you that they've gathered through this ad tech surveillance system.

Brooke: Which includes what?

Cory: Everything you've bought, everywhere you've gone, everything you've looked at, all the people you know, your age, your address, everything. They say, "I have here one Brooke Gladstone, NPR host and proud New Yorker who last week was thinking about buying an air conditioner for her apartment." They say, "What are my bid for this Brooke Gladstone?"

That goes off to one of these ad tech platforms. The ad tech platform asks the advertisers, and they say, "Who among you will pay me for Brooke Gladstone?" There's a little auction that takes place. If you've ever noticed that the page lags when you're loading it? That's the surveillance lag, right? That's the auctions, dozens of them, taking place at once.

Brooke: What? How do I not know this?

Cory: Yes, it's terrible, right? Bandwidth gets faster, pages get slower, and it's the surveillance lag that's doing it, all this busy marketplace stuff happening in the background.

Brooke: Even if an ad company fails to win your behavioral ad auction, the process still gives them a lot of insight into your behavior. Whereas with context ads, they mostly have access to what's relevant and obvious.

Cory: You are reading an article about the great outdoors, and they look at your IP address and they go, "This is someone in New York." They say that you're using an iPhone. It's someone who has $1,000 to buy a phone, and they say to the marketplace, "Who wants to advertise to someone in New York who's reading about the great outdoors?" The same thing happens, and you get an ad, but the ad is not about you. It's about what you're reading.

Brooke: Not your Google searches or your health concerns or what's in your email address book.

Cory: If Congress says we're going to pass a comprehensive privacy law, the industry would have to respond with context ads.

Brooke: That's one potential privacy fix, but we need more than that. The legislative focus seems to be on children's privacy. Do we have a model in the Child Online Protection Act?

Cory: We could if we ever bothered to enforce it. COPPA says that you can't gather data on people who are under 13. If you recall, when poor Shou Chew, the CEO of TikTok, was being grilled by Congress, there was a congressman from Georgia who was just weirdly horny for whether or not pupils were being measured.

Congressman: Can you say with 100% certainty that TikTok does not use the phone's camera to determine whether the content that elicits a pupil dilation should be amplified by the algorithm? Can you tell me that?

Shou Zi Chew: We do not collect body, face, or voice data to identify our users. The only face data that you will get that we collect is when you use the filters to have, say, sunglasses on your face. We need to know where your eyes are.

Congressman: Why do you need to know where the eyes are if you're not seeing if they're dilated?

Shou Zi Chew: That data is stored on your local device and deleted after use if you use it for facial. Again, we do not collect body, face, or voice data to identify our users.

Congressman: I find that hard to believe. It's our understanding that they're looking at the eyes. How do you determine what age they are, then?

Shou Zi Chew: We rely on age gating as our key age assurance.

Congressman: Age?

Shou Zi Chew: Gating. Which is when you ask the user what age they are. We have also developed some tools where we look at their public profile to go through the videos that they post to see whether--

Congressman: Well, that's creepy. Tell me more about that.

Shou Zi Chew: It's public.

Cory: He's just baffled. Rather than the congressman from Georgia saying, "Wait, this is what everybody does? That's terrible." He says, "We're not here to talk about your American competitors. We are here to talk about what you're doing for Xi Jinping." You know what? They're all doing that.

Brooke: The Child Protection Act doesn't really do anything?

Cory: Does it? I mean, can anyone with a straight face look at Congress' legislative intent in passing a rule? On the one hand, they pretty definitely don't mean measure people's pupils and do some digital phrenology to figure out if they're over 13. On the other hand, they didn't mean give everyone a box that says, "I'm over 13." I mean, there's another way of thinking about this, which is to say, "Don't spy on anyone in case they might be under 13."

Brooke: That's how Congress is reaching back for some old-school antitrust-style legislation.

Cory: Mike Lee has got a bill right now that both Elizabeth Warren and Ted Cruz has sponsored, and it says that, at a minimum, the ad tech business should be broken up so that you can be a company that provides a marketplace where people buy and sell ads, or you can be a company that represents publishers in that marketplace, or you can be a company that represents advertisers in that marketplace. You cannot in the mode of Google and Meta be a company that is the marketplace that represents the buyers, and represents the sellers.

Somehow, even though you claim that this is a very clean arrangement, the share of money going to publishers keeps going down. The cost to advertisers keeps going up and your margins keep increasing. We could say that you can have a platform, or you can use the platform.

Brooke: Platforms claim that reigning in privacy would break the internet. They say the same thing about taking step two when Dr. Rose program to pull big media from the dong heap. Step two is interoperability.

Cory: When you buy a pair of shoes, you can wear anyone's socks with them. In theory, when you buy an iPhone, you could run anyone's software on it. There is this latent computer science bedrock idea that is very important, but esoteric, I apologize in advance, called Turing completeness, named for Alan Turing, the great Hero of Computer Science. Turing completeness, it says that the only computer we know how to make is the one that can run all the programs we know how to write.

You could hypothetically write a program that would allow you to install a different operating system on your iPhone, or a different app store on your iPhone. The real thing that prevents it is that, if you tried it, apple would destroy you with lawsuits. They'll drum up a thousand excuses that today we call IP, which colloquially just means anything that allows me to control the conduct of my competitors, my critics, or my customers.

Brooke: Like inducing confusion by turning knobs, by--

Cory: Twiddling. Twiddling is the ability to change the business rules very quickly. There are no real policy constraints on twiddling.

Brooke: Cory says, "Three factors gave rise to the new world of big digital and made en-bleep-fication inevitable."

Cory: The first is no competition. For 40 years, we let these companies buy their competitors. We let them do predatory pricing. We let them violate the antitrust law that was on the books because Ronald Reagan said that we shouldn't enforce it the way it was written. All of his successors, until Biden said, "That sounds like a good idea to me too." On the one hand, there's just nowhere else to go.

Then you have digital is different. The platforms can play this high speed shell game because there's no rules on how they can change the rules. There's no rules on how they can alter your experience or harvest your data or do other things that are bad for you.

Then finally, we can't use the intrinsic property of computers, this universality, this Turing completeness to step in where Congress has failed and put limits on their twiddling ourselves by changing the technology so it's twiddle resistant, so that when they try to spy on us, our computer says, "I'm sorry. No, I belong to Brooke not Mark Zuckerberg." Even though you've requested that private data, I am not going to furnish you with it.

Brooke: No competition and unbridled twiddling are the first two factors kettling users. The third taps into feelings many of you have had. You can't stay, but you can't go because, if you do, you leave your community behind, your history. You can't take it with you.

Cory: There's no right to exit. Facebook gives you this Sophie's Choice where either you go and you do what's best for Brooke, the individual, or you do what's best for Brooke, the member of a community. If you leave, you leave the community behind. Now, we could just make this a rule. We could say, if you have some user's data and the user asks for the data, you got to give them the data.

Then we could say to a company like Twitter that is just cruising for a bruising from consumer protection agencies and is probably going to be operating under a new consent decree, "Hey, your consent decree, now that you've abused your users, is you've got to support this standard so that users can leave, but continue to send messages to Twitter," and they can take their followers with them if they leave, and they can take their followees.

[music]

Brooke: To recap, to reverse the degradation of our online experience, we rest some control of our privacy by insisting on ads that collect only context rather than every known morsel of information about our earthly lives, then sue for interoperability. The right to use what we own from books' detractors and slap away the seller's cold dead hand. Finally, we lay claim to our right to exit. The simple idea that signing out of social programs should be as easy as signing up.

All these would take lots of public pressure, but all are possible. In fact, they were normal parts of our online experience, all of them, before being thrown on the dung heap with mission statements vowing to give people the power to build community, protect the user's voice and not be evil. Big digital's current mission statement should be, it gets worse before it gets worse. I wonder, has anyone ever stopped the process in its tracks? Have users ever rebelled before a platform or a service went south?

Cory: Well, I've got some good news for you Brooke, which is that podcasting has thus far been very en****ficationresistant.

Brooke: Really?

Cory: Yes, it's pretty cool. Podcasting is built on RSS.

Brooke: I know that. It stands for Really Simple Syndication, that lets pretty much anyone upload content to the internet that can be downloaded by anyone else. In turn, podcasts are extremely hard to centralize.

Cory: Which isn't to say that people aren't trying.

Brooke: Like Apple.

Cory: Oh my goodness, do they ever? YouTube. Spotify gave Joe Rogan $100 million to lock his podcast inside their app. The thing about that is that, once you control the app that the podcast is in, you can do all kinds of things to the user. You can spy on them. You can stop them from skipping ads. The BBC for a couple of decades has been caught in this existential fight over whether it's going to remain publicly funded through the license fee, or whether it's going to have to become privatized.

It does have this private arm that Americans are very familiar with, BBC worldwide, and BBC America, which basically figure out how to extract cash from Americans to help subsidize the business of providing education, information, and entertainment to the British public.

Brooke: The BBC created a podcast app called BBC Sounds.

Cory: That's right. One of my favorite BBC shows of all time is the News Quiz.

Show Host: Welcome to the News Quiz. It's been a week in which the culture sector is suggesting the BBC needs to look at new sources of funding, so all of this week's panelists will be for sale on eBay after the show.

Cory: You can listen to it as a podcast on a four-week delay. You can hear comedians making jokes about the news of the week a month ago, or you can get it on BBC Sounds. From what I'm told by my contacts at the B, people aren't rushing to listen to BBC Sounds. Instead, they're going, "You know, there is so much podcast material available more than I could ever listen to. I'll just find something else." That's what happened with Spotify too.

Brooke: Spotify paid big bucks to buy out production houses and big creators like Alex Cooper and Joe Rogan in an attempt to build digital walls around their conquests popular shows just to see their hard one audiences say, "I'll pass."

Cory: Now, Spotify is making all those pronouncements. We are going to, on a select basis, move some podcasts outside for this reason and that, and basically, what's happening is they're just trying to save face as they gradually just put all the podcasts back where they belong on the internet instead of inside their walled garden.

Brooke: Maybe it's because there's so much content or because, like the news business, people are used to getting it for free. Podcasting seems resistant even though no medium is safe from what Doctorow is describing, and en-bleep-ification sits at the intersection of some of our country's most powerful players, entrenched values, and the consumer's true wants and needs.

Cory: I have hope, which is much better than optimism. Hope is the belief that, if we materially alter our circumstance even in some small way, that we might ascend to a new vantage point from which we can see some new course of action that was not visible to us before we took that last step. I'm a novelist and an activist, and I can tell the difference between plotting a novel and running an activist campaign.

In a novel there's a very neat path from A to Z. In the real world, it's messy. In the real world, you can have this rule of thumb that says, "Wherever you find yourself, see if you can make things better, and then see, if from there, we can stage another climb up the slope towards the world that we want."

I got a lot of hope pinned on the Digital Markets Act. I got a lot of hope pinned on Lina Khan and the Federal Trade Commission's Antitrust Actions, and the Department of Justice Antitrust actions. The Digital Markets Act, and the European Union, the Chinese Cyberspace Act, the Competition and Markets Authority in the UK stopping Microsoft from doing its rotten acquisition of Activision.

[music]

Cory: I got a lot of hope for people who are fed up to the back teeth with people like Elon Musk, and all these other self-described geniuses, and telling them all to just go to hell. I got a lot of hope.

[music]

Brooke: Thank you for taking me on this journey with you. I am inspired. [laughs]

Cory: Thank you for coming on it.

Brooke: Journalist, activist, novelist, Cory Doctorow. His most recent novel is Red Team Blues.

Brooke: That is our show. On the Media is produced by Micah Loewinger, Eloise Blondiau, Molly Schwartz, Rebecca Clark-Callender, Candice Wang, and Suzanne Gaber. Our technical director's Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Andrew Nerviano. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.