Takeaway060519-prisonbooks

Transcript

(HOST) Tanzina Vega: The battle over access to educational materials for inmates is national and enduring. There are more than 2 million incarcerated people in the United States and for many of them, access to books and other learning materials is not guaranteed and can sometimes even be purposely denied.

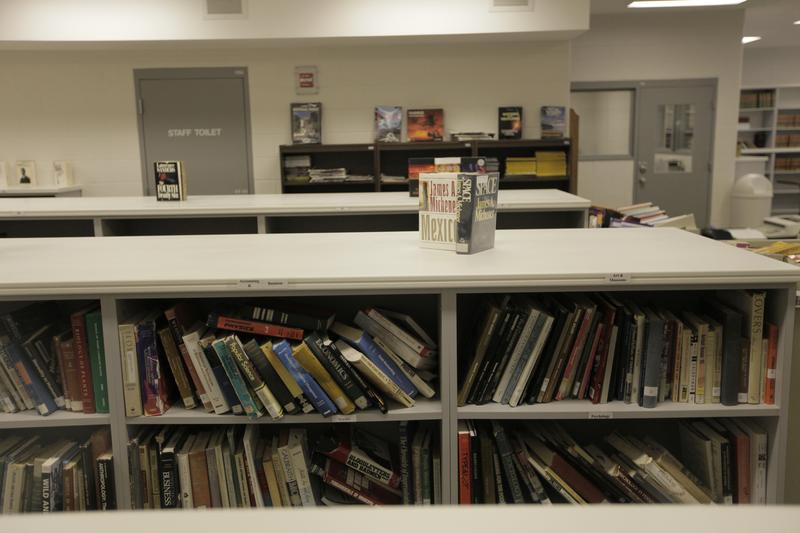

One Illinois prison recently removed more than 200 of its books, many of them about race from its library. An organization called the education justice project or EJP provides college level courses to inmates at the Danville Correctional Center and as part of their program, the EJP had built up a library of over 4,000 books in the Danville prison. Each of those books went through a review process to get there.

EMBEDDED CLIP

Lee Gaines: The Illinois Department of Corrections has a publication review policy. Something can be disapproved because it's obscene or it's sexually graphic or it encourages violence or hatred of other groups. The other criteria that they use is a little bit more vague. They say anything that might be detrimental to the safety and security of the prison, which probably could be interpreted in a lot of different ways.

Tanzina Vega: That's Lee Gaines, an education reporter at Illinois Public Media and Lee says the program has been running smoothly until last fall when a number of books were unexpectedly rejected by the Department of Corrections. Then early this year the program hit another snag.

EMBEDDED CLIP

Gaines: In January, the entire program was suspended for an unknown reason and during that time staff at the Danville prison went into the EJP library and removed 202 books from the shelves. And then they forced the EJP staff to take all of these books back to the University of Illinois campus and that is currently where they are.

Tanzina Vega: To learn more, I spoke with Lee and with Heather Ann Thompson, a historian at the University of Michigan and author of Blood In the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy and I asked Lee first why Illinois prison officials say that they removed the EJP’s books in the first place.

Gaines: I interviewed the outgoing director of the Illinois Department of Corrections and what John Baldwin told me was that these books didn't go through a review process. And when it was discovered that they didn't go through the review process, they were removed from the library. After I had that conversation with Director Baldwin, I was able to obtain emails that show that at least a portion of these books were reviewed and were approved to enter the facility by prison staff.

I've since gone back to the Department of Corrections and said, do you still stand by this rationale that the books were removed? Because they weren't reviewed despite this evidence that I found that shows that at least some of them were reviewed and improved. And the short answer is yes. They sent me a statement. They say that they also want to review the books and return them to the facility and while we have not yet received them back from the Education Justice Project, we remain hopeful this will occur.

Tanzina Vega: Heather, you have written a book about the Attica prison uprising that has been banned in many prisons, including prisons in Illinois. What reasons have you been given, if any, for those bans?

Heather Ann Thompson: Well, often there are no reasons given and that's one of the worst elements of this censorship. Oftentimes, the folks who have requested the books, the folks on the inside are not told why they were not given the book that they asked to receive and oftentimes the person sending the book and in many cases that's myself is not told why the book was denied.

And in fact, often they accept the book and the book just disappears into the bowels of the prison and you don't really know what happened. To the extent that I do know in the case of my book, it's usually security concerns that are cited, which is the blanket explanation for why many books are not allowed in and in.

In my case, it may seem on the surface that it would make sense. It's a book about a prison uprising in 1971, but in fact, content aside, it is every person's right to keep their brain alive, even if they're incarcerated. And in the case of my book, ironically, if they actually read it, it's a primer for how to avoid a prison uprising and how to keep prisons run in a humane fashion that would avoid the kind of violence that happened at Attica.

Tanzina Vega: I'm curious about a little bit more about what exactly those who are incarcerated are feeling. Lee, you spoke to a, someone who was formerly incarcerated, his name is Michael Tafoya. Let's take a listen to what he told you about the value that he places on books.

EMBEDDED CLIP

Tafoya: Yes. People like me that come from a poverty stricken neighborhoods, learn how to be much more and value ourselves, and we're going to be less likely to be breaking the law. And if that happens, then less people are going to go to prison. Less people go to prison and that means there's going to be less prisons. That means that a lot of people are going to be out of jobs in the future.

Tanzina Vega: Lee, tell me a little bit about Michael Tafoya.

Gaines: So Michael Tafoya grew up in Chicago. He grew up in a poverty stricken area, as he describes, and he was convicted on a murder charge when he was 18 years old. He spent 20 years in prison in Illinois. And during that time, he went through a kind of self transformation and a lot of that was driven by his access to education and his access to literature. So, he developed a level of self-awareness.

He told me at another point during our conversation that reading books, like the kinds of books that were removed from the EJP library, showed him how he became a part of the system of mass incarceration. And how it doesn't make sense to continue a life of crime. That the better way to fight that system is to empower people like himself, people of color, people from poor neighborhoods.

So that's how he described his experience.

Tanzina Vega: What does this say about our First Amendment, about the ability for people to obtain knowledge even if they're incarcerated?

Thompson: Well, for starters, it's a real reflection of just how punitive our culture has become. Most of these questions were resolved in a critical prisoner rights cases in the 1960s and 1970s. And censorship was an issue then. It was litigated. It was actually one of the reasons why prisoners at Attica rebelled -- it was the level of censorship in their own prison. And we had really come to a point where that was on the wane. Now we are yet again at this moment where we are preventing people from reading.

And the knee jerk reaction when people hear this is, “Well, that's not a surprise, you lose your rights when you go on prison.” And actually, you don't. There is nothing inherent in a sentence that says that when you are inside, you cannot read, for example. So this is returning to an older level of punitive response to prisons and it's used very capriciously to punish people.

Tanzina Vega: And I'm wondering, Lee, bringing us full circle here, going back to Danville Correctional Facility, what's happening there? Will there be an opportunity for the incarcerated folks there to actually have access to some of these books?

Gaines: So, according to the Department of Corrections, yes. And my understanding from the director of this Education Justice Project, Rebecca Ginsburg, is that she would like to submit the books through a review process. She and other advocates for the expansion of education in prisons in Illinois are launching a campaign, and it's called the Freedom To Learn campaign.

And what they're asking for, among other things, is that they have a transparent and a fairly applied book review process across the entire Illinois Department of Corrections system. And that there's also an appeals process that's part of that review process. So, if a book is denied, that there's some way to challenge that denial on the part of these advocates. That's something that they're fighting for. And right now, they're trying to get lawmakers and other organizations on board with their cause

Tanzina Vega: Lee Gaines is an education reporter at Illinois Public Media and Heather Ann Thomson is author of Blood In the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. Thanks to you both.

Gaines: Thank you.

Thompson: Thank you.