Dreaming of a Deaf Utopia

( Peter Musty, Urban Designer and Peter Harmatuck )

MARY: Hey guys, this is Mary Harris and we want to start this episode with a little bit of a clarification. Amanda Aronczyk is here with me.

AA: So last episode I told a story about a guy named Jay Zimmerman, and he was desperately desperately looking for a cure for his hearing loss. And re had the option of joining an experimental trial...

MH: Right, but in the end, he didn’t do it.

AA: He didn’t feel sure enough that it would work and so he decided to wait. But, I did something disingenuous in that story - I used the world “cure” and that word is really loaded. And it was the doctor who was running the trial who told me that. And he said that the medical community has a long and not very proud history of trying to cure deafness. This is what Dr. Lawrence Lustig said about it:

LUSTIG: We should be ashamed. As the deaf community will tell you, that’s uh, hearing is one way to be. Deaf is another way to be, it’s a value judgment.

MH: Ashamed is a really strong word.

AA: I know. On one hand you have this incredible research that’s going on that could help millions of people who’ve had hearing loss or who are deaf. But there are people in the Deaf community who see deafness as “another way to be.” It’s like being short, or being gay. And they don’t want to be “cured” of anything. So eventually the researchers come to using the word “treatment,” instead of “cure.”

MH: Ok so what does this have to do with today’s story?

AA: Well the whole idea of options for people who have hearing loss or who are deaf made me start to wonder, what would be lost if everybody who couldn’t hear could could hear? And the thing that is at risk is Deaf culture and American Sign Language. And that is when I heard this amazing story about a man who went to extreme lengths to try to protect that culture.

MH: This is Only Human. A show about how our bodies work and how they shape who we are. In this episode: one man’s vision of a sign language utopia on the great plains. Amanda, you’ve got it from here.

AA: This past spring, I went to Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C. to try to find this man – Marvin Miller.

AA: Hello! How are you?…

AA: You only hear me, because Marvin doesn’t speak. And as you might already know, Gallaudet is a university for Deaf and hard of hearing students. Marvin is finishing up his B.A. after a 24-year hiatus. We’re communicating through several interpreters. It’s complicated. But basically what you need to know is that the voice you’re going to hear — it’s not Marvin. But you can hear his laugh a little here, after I say:

AA: Marvin, your dreams are not small. (laughs)

AA: You hear it just a little. Now I said that to him - that his dreams weren’t small, because when Marvin Miller was kid, he had a vision... of building a town.

MILLER: I was probably 8 years old.

AA: It was 1980. He lived in New Lothrop, Michigan, population 564.

MILLER: I remember riding a school bus… I was going to school for the deaf.

AA: Every day he would take the bus 20 miles to Flint.

MILLER: And I was chatting with a friend of mine…

AA: In sign language…

MILLER: And I remember on the school bus I said you know why didn't we have a town where everybody signs?

AA: A town where neighbors meet outside, watering their lawns, signing hello…

MILLER: Where we could have a deaf mayor, we would have deaf entrepreneurs…

AA: Deaf would be the norm…

MILLER: The garbage truck driver would be deaf in that town.

AA: And it would be no more remarkable than wearing glasses, or being bad at baseball. That is what Marvin’s childhood was like.

MILLER: My parents are deaf and my grandparents are deaf…

AA: He’s a deaf child of deaf parents. That makes him what’s called Deaf of Deaf. And in the unspoken hierarchy that all groups seem to have, that puts him at the top in his community.

MILLER: Deafness was just a regular part of my everyday experience.

AA: When he was a kid and someone new moved into the neighborhood, he wondered what was wrong with them if they couldn’t sign, too. It was only as he got older that he realized his family was the only deaf family in town. So that dream of the Deaf town, it’s outline grew sharper. And by the time he was 32 years old, he had found the place to build it.

MILLER: It was farmland. It was just adjacent to the interstate. There was a pond there in the middle of the land and it was a parcel of 380 acres. We were going to start from scratch and build a whole new town right there on that land. And it was a nice dream.

AA: Marvin had found a place for his Utopia. Let me tell you what happened. There are many people — Mormons, Jews, African Americans — who have at some point in their history asked themselves: If we could have a place of our own, would we be better off? Do we need it for our survival?

Marvin’s idea for a Deaf community wasn’t new. He sees a problem that he thinks never resolves: Be together and use sign language? Or be out in the world and be forced to speak?

ARCHIVAL TAPE: Good afternoon, this is Ben Park, and this is the program, “It’s Your Life”…

AA: This health show from the 1950s promised “living drama straight from the real lives of your friends and neighbors…” In this episode called, “No Such Thing as Deaf and Dumb,” a reporter watches a teacher instruct a four-and-a-half-year old girl who doesn’t hear well….

ARCHIVAL TAPE - TEACHER: Look, sweetheart. What’s this?

AA: The teacher points to pictures in a book…

ARCHIVAL TAPE - TEACHER: Horse…

KID: Horse.

TEACHER: That’s better. What’s this?

KID: Co—

TEACHER: Cow.

KID: Co- Ugh.

MAN: Why is she having trouble with this? Is that a hard sound…

AA: The girl watches the teacher’s mouth and tries to make that same “k” sound. But try it, that “k” sound is made right at the back of the throat. If you’re watching someone’s mouth move, you’ll never see that sound…

ARCHIVAL TAPE - TEACHER: Now look. I’ll hold the front of her tongue down, with the tongue depressor. Listen, say, coffee!

KID: Coffee-

TEACHER: Listen, say, coffee!

KID: Coffee- …

AA: Teaching someone who can’t hear how to speak can be brutal work. Kids aren’t subjected to treatments like this anymore. But for the overwhelming part of the last century, many doctors and educators insisted on it… Marvin Miller calls it an assault.

MILLER: People being forced to speak and lip-read. People not being able to sign or being banned from signing….

AA: He says the overwhelming message has been: we will make you speak.

MILLER: I really call it a war for the past 135 years.

AA: Using sign language was failing to live in the wider world.

M.E. BARWACZ: You've always had a microwave, right?

AA: This is M.E. Barwacz. She was Marvin Miller’s mother-in-law.

BARWACZ: Are you old enough to have grown up without a microwave oven?

AA: I'm 41 and we had a microwave, but it was it was an old one, but yeah we had one.

BARWACZ: You had one. Well I'm 65 so when I grew up I didn't have one. So I never walked around as a teenager or a young mom or even a middle-aged mom saying, “I need a microwave, I need a microwave, I need some way to make chips and cheese, I need some quick fast way to heat up my leftovers.” I didn't miss it because I never had one, nor did I ever dream of what it might be… and if you are born deaf in a community where people sign, you're not losing something you never had and you have a wonderful life. My grandchildren were born. They came out and we signed to them, “Hello and welcome to the world.”

AA: M.E. isn’t deaf, but she carries the gene — some hearing loss is hereditary — and one of her daughters, Jennifer, was born deaf. Jennifer and Marvin Miller, the guy who wanted to start the town, grew up near each other in Michigan.

BARWACZ: They knew each other, they had nothing to do with each other, Jennifer was the spunky little cheerleader, Marvin was the nerd and I'm sure did the newspaper.

AA: They met again at Gallaudet, got married, had kids. M.E. said from the moment she met her new son-in-law, Marvin talked about building his dream town. He was losing patience.

BARWACZ: He just wanted to be together he didn't want to have to deal with hearing people, wanted to do things his own way. And you've talked to him so I don't want to put words in his mouth. But basically I sat down one day and said, “Marvin, if I introduced you to people who make towns happen would you be interested, are you serious?” And he about jumped up and hugged me and said, “Are you kidding? Of course!”

AA: M.E. had worked in real estate development, and was inspired by “New Urbanism”...

NPR NEWS: A new kind of town was built along the Florida panhandle, and was called Seaside.

AA: A movement that built towns the old-fashioned way: homes with porches, a town square, no high-rises. Places where people walk instead of drive. A town called Seaside is probably the most famous.

NPR NEWS: Today, the movement that began in seaside called New Urbanism has become enormously influential.

AA: Marvin and ME looked at looked at places like Seaside and thought, we could do this too.

BARWACZ: We met the people, and found out all of these people that are building new urban towns, all across the country.

AA: In 2004, M.E. and Marvin decided to become business partners. Marvin’s wife supported them, but she wasn’t directly involved. It was Marvin with the vision, and his mother-in-law was the voice.

AA: I think it’s interesting, I mean to me, it’s definitely like wow, that is a big idea I've never had that big an idea frankly, you know, I'm like “Oh I want to raise my kids and I want a job.” I never thought like, “Oh, tomorrow I'll start a town.”

BARWACZ: Well and, you know all those things are important, but the bottom line is that if you are deaf... you have many people that never communicate with you. My daughter - I see people who just kind of ignore them because their deaf. You wave out at them when they come and go if they're your neighbor, you know, they got a new car you give them a thumbs up, the weather's really bad you go over and say “Hey, you want me to help shovel out yours..?” But you don't get to know them. You don't know their names, you don’t know where they’re from, you don't know their history… You don't come over and sit around for an evening and visit, you know, you're not part of even your neighborhood.

AA: So M.E. Barwacz and Marvin Miller started to plan a town. They named it Laurent, after Laurent Clerc, who was a deaf educator. And they didn’t want some crappy subdivision, but a real town, like the towns that they’d grown up in. They wanted a high school and a performing arts center, a public pool and a donut shop. There would be town council meetings with debates over parking laws and off-leash dogs. A real old fashioned all-American town. In sign language. They had $300,000 but they knew that they needed more. So they quit their jobs to focus on raising money. Then everything started moving really fast. A friend suggested that they meet with a potential investor, and immediately, he said…

BARWACZ: We would like to make this happen for you financially.

AA: Wow.

BARWACZ: Yeah, we kind of picked our jaws up off the floor and said, “OK, be a little more specific, go through that again.” So we were picked up by angel investors who felt they could make this happen.

AA: Now where do you build your dream town? You might be thinking Florida or California. But Marvin Miller wanted to be somewhere with fewer people. He had a very specific purpose for his town. Believe it or not, the United States has never elected a deaf person to any real position of political power. So Marvin picked 380 acres of farmland in a place where it would not take long to get some political clout: McCook County, South Dakota. Population: 5,809.

AA: Marvin Miller moved his wife and his four kids to South Dakota and M.E., his mother-in-law and business partner, she moved there too. They set up the Laurent Company and then hired a firm called Nederveld, and designer Terry Sanford, who is a developer and sort of a dream maker…?

SANFORD: A little bit yeah.

AA: You build utopias.

SANFORD: Yeah, I think we all set for high ideals.

AA: Sanford went to see the land, and he found that the soil was good. The topography was fairly level, and zoning didn’t seem to be a problem...

SANFORD: So we were kind of like, “this is a little bit like a development utopia,” as long as you really have a base of people that want to live in South Dakota, we don’t feel like there’s a lot of difficulties here….

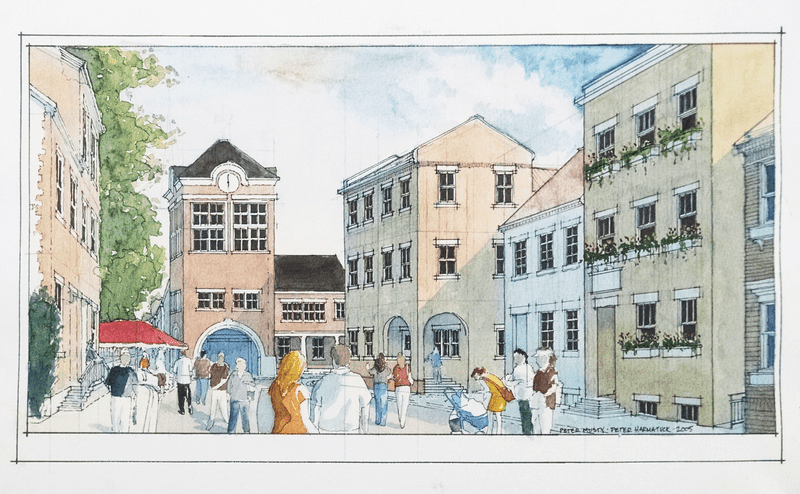

AA: So he and his team start making plans and drawings of Laurent based on Marvin’s vision…

AA: Can you describe what it might have been like to walk around?

SANFORD: Yeah, yeah definitely, it looked a lot like a European town…

AA: They had traveled to look at many towns, and something felt right about Quebec City.

SANFORD: We used a lot of imagery from the old town in Quebec City.

AA: They liked the closeness, and the intimacy…

SANFORD: Real narrow, quirky streets, real tight architecture.

AA: They wanted to have lots of sunshine...

SANFORD: A lot of windows, they really needed to be very visual and that was important to them.

AA: The land was very close to where “Little House on the Prairie” was set.

AA: Oh it’s a house on the prairies with Quebec City plopped on top of it.

SANFORD: Yeah, yes.

AA: Did the locals feel like you guys were crazy?

SANFORD: Yeah, I think there was a fair amount of that, sure.

AA: The area is surrounded by open fields and large farms. And not the we-have-a-few-chickens-in-our backyard kind of farm, but the we-have-two-thousand-hogs-in-our-warehouse kind of farm.

AA: Did it smell around there?

SANFORD: We didn’t experience that, although the neighbors warned us that, I believe the one phrase that stuck with me was flies of Biblical proportions.

AA: No kidding. Uh oh.

SANFORD: Yeah.

MARY: This is Only Human, I’m Mary Harris. We’re gonna take a short break. When we come back: how Marvin won over locals who wished he had takeN his idea somewhere else. Stay with us.

--

MARY: This episode of Only Human is one of a few we're doing about how we hear the world. But no matter how well you hear, you might not be a particularly good at listening.

We want to help you with that too - with our project called “Listen Up.”

Here’s how it’s going to work: starting Monday November 16th, we’ll give you a mini-podcast every day, Monday through Friday, instead of one big show for the week.

Each day we'll focus on something new, like reading body language or emotional cues, or paying attention. And we’ll give you a challenge designed to help you get better at the thing we’re focusing on that day.

Here’s how to play along: head over to our website: onlyhuman.org. We have a quiz there right now that will help you figure out what kind of listener you are. Then, subscribe to the show. And listen. Pretty simple.

Who hasn’t been told at some point, “You’re not listening to me”?

So, subscribe to the show. Take the quiz at onlyhuman.org and learn along with us next week.

--

MARY: This is Only Human. And when we left off, Amanda Aronczyk was telling the story of Marvin Miller, who dreamed of creating a kind of deaf utopia, an entire community where people would communicate using sign language. Marvin and his business partner found a spot in South Dakota, and they had plans drawn up. Here’s Amanda.

AA: The town of Laurent was controversial within the Deaf community. It reignited an old fight: isolate or integrate? The New York Times summed it up: “As Town for Deaf Takes Shape, Debate on Isolation Re-emerges.”

AA: And media of all stripes showed up - CNN, BBC, People Magazine… even our own NPR….

NPR NEWS: …Now South Dakota Public Radio's Curt Nickisch has the story of some people who have their eye on a patch of prairie for a new community of signers.

CURT NICKISCH IN TAPE: Summer in the city of Sioux Falls. Kids are sliding across a lawn on a wet plastic mat…

AA: Can you hear yourself?

NICKISCH: Yeah, yeah I can.

AA: This is Curt Nickisch. His family is from South Dakota. He was a reporter there for 7 years. I played him this story that he reported a decade ago.

AA: Do you think you sound like you, but more naive and younger and innocent?

NICKISCH: Yeah, pretty much. Unadulterated by the East Coast at that time.

NPR NEWS: They want to name it Laurent, after the man who brought sign to America…

AA: At the time, Curt wanted to get a sense of what the locals thought of Laurent, so he drove 3 miles down the highway, and stopped in at the Home Motel… Curt said The Home Motel was not the kind of place you find on Expedia. It was family run, reservations by phone. And Connie Weber, she didn’t much like the idea of a sign language town next door.

CAROL WEBER: Why should we have to change our whole entire lifestyle because these people have an idea. It's their dream not mine.

AA: She couldn’t understand it. What would happen if you wanted order or burger in Laurent? Or if your Chevy broke down nearby? What if the locals didn’t understand their new neighbors?

CAROL WEBER: It just seems like they want their own little world. Well, they decided that McCook County was a place to carve it out. And I wish they would have ff-found a place in Timbuktu and leave our lives alone.

AA: Was she going to swear?

NICKISCH: She's just you know, not welcoming at all. For somebody who works in the hospitality industry.

AA: Curt said that while not everyone shared her strong opinion, at first a lot of the locals shared her fear. Which he thought was really too bad.

NICKISCH: You know I just I feel like they had so much in common. In a way.

AA: Marvin Miller wanted to move to South Dakota to start a new life. Exactly as Connie Weber’s great grandparents had done more than a century ago. It’s the land they chose.

NICKISCH: You know, everybody there says it's the greatest state and it's sort of it's what you say, it's like we live in South Dakota, it's the greatest state and of course, it's not the greatest state. But they're there because the people that they love are there, the land that they grew up on is there, and it's just is just who they are now.

AA: People came as immigrants and homesteaders trying to stake their claim on the Prairie. The Deaf community was just the most recent iteration of that very same dream.

NICKISCH: Which is a beautiful thing. I mean it's such a, it's such a beautiful notion.

AA: So M.E. and Marvin Miller did not win over all of McCook County, South Dakota in that year they spent meeting with locals, with officials, with local officials… But by the time they held a kind of town hall meeting a few months later, things were looking more hopeful. The designers came to town for a week. They showed everyone their plans. People stood up and said, I like this, I hate that – and the designers adjusted accordingly. The guy who ran it said that these meeting have a proper cooking temperature – you need enough heat to make it work, but not so much that everything burns.

SANFORD: When we finally got to the last night…

AA: The designer, Terry Sanford, he said the room was packed. Which is hard to do in a sparsely-populated place like McCook county. Marvin got up and he presented the plan for Laurent – the narrow streets, the town square… and the people were sold.

SANFORD: I think at the end it was almost a celebration, like when can this get started?

AA: Sanford said that sometimes when you’re collaborating on a design, all you see is compromise. Not with Laurent. Everybody loved it.

SANFORD: It was just ah.. it was a great moment.

AA: Families from all over South Dakota signed up to move there as soon as the town was ready. Then families from Michigan, Missouri, Illinois, Maryland, Virginia signed up… Then Australia, the UK… All told, 150 families wanted to know: when can we move in?

SANFORD: I mean, people were going to uproot their lives and there wasn’t anything they weren’t willing to leave.

AA: Everyone I spoke with felt sure that Laurent was about to be built.

BARWACZ: Well yes, definitely.

MILLER: I believed it would happen with all my heart and soul.

KSFY NEWS: The plans are impressive. The economic development could be staggering. But work on the sign language community of Laurent is on hold…

AA: Not long after the celebration, Laurent had to stop. The money to build the town was quickly running out…

AA: So what is the first thing that happens that makes you realize that it might not work out?

BARWACZ: Our…for 18 months our angel investors said we're going to close on this in two weeks, we should be doing it in two weeks, we should be doing it in two weeks. Don't ever tell me you're going to do something in two weeks, Amanda. (laughs)

AA: How much do you think you lost?

BARWACZ: Oh, personally? Probably about a quarter of a million dollars.

AA: Wow, that's a lot of money.

BARWACZ: Oh yes, oh yes. Financially, Marvin and I both lost everything we had.

AA: Remember the angel investors? After a year and a half of promises, they didn’t come through. M.E. and Marvin lost everything. The design firm lost over $300,000. Marvin and his family quit South Dakota and moved to Indiana. When I called M.E. this past summer, she said it was the longest she’d spent reminiscing since it happened a decade ago. I asked her if she took any pleasure in digging up all these old memories.

BARWACZ: Oh it's a double-edged sword. You know, deafness isn't going to go away. And like I said I hope someday somebody will build a town. Not just a vacation town, not a retirement village, but a vibrant town where people like me who are, are hearing parents who now find out they have a baby whose deaf can say, “Honey, we’re moving to Laurent.” We’ve got to have our kid grow up where they’re part of it.

AA: We all have our reasons for doing what we do. There are the reasons we tell others and then there are the real reasons. M.E.? She said she wanted to build a sign language town. And that was one reason, but there was also a more personal one. She really wanted her family to be together. Over the past year she has watched all the people she loves move away.

BARWACZ: Here I am watching my family move off. They're going to be all scattered when… the whole intent of building Laurent was to have a place to put down roots.

AA: For Marvin building Laurent was something different. It was a calling. Here he is, speaking through an interpreter again.

MILLER: What we went through was a beautiful experience. It was beautiful, but very difficult particularly the end when we realized it wasn't going to work.

AA: Although he didn’t offer a lot of details, shortly after Laurent failed, his marriage fell apart too.

MILLER: It was very difficult. I mean it was tough on the family and particularly tough on me, I had four deaf children and so I was a family man so dealing with those challenges... But I felt like we were so close and then not to make it was very difficult for me.

AA: Last year, after 24 years, Marvin decided to go back to college to finish that degree he had started. That’s why he’s back at Gallaudet, the university for deaf and hard of hearing students.

AMBI FROM GALLAUDET GRADUATION: Welcome graduates, families and friends to Gallaudet’s 145th Commencement ceremony…

That same week that I went to speak with Marvin Miller also happened to be the school’s graduation. Everyone had gathered in the campus’s main hall, and a drumline marched up the aisle. If you can’t hear drums, you can certainly feel them. The entire room was vibrating.

There are three jumbo screens so you can see all the speakers signing, plus there’s closed captioning. Each student appears on stage - they pause, wave, hug a teacher. They cry. We cry.

AMBI FROM GALLAUDET GRADUATION: Congratulations to the class of 2015! (cheers)

AA: Graduation here is not like at other schools. People describe Gallaudet as a home. Or a birthright. And when Marvin graduates, he’ll be going back to a world where people don’t speak his language.

Marvin still has two years left in his BA so he wasn’t graduating. But he’s happy to be back on campus, communicating in sign language. He’s in the majority here.

MILLER: We have Gallaudet University and this is a community and it's an important community… It's a place of academic learning, it's a place where people have a good time and party and it's very important.

AA: But there’s one thing it’s not.

MILLER: But it's not a town.

AA: A few months after I spoke with Marvin Miller and M.E., I realized that I’d never actually looked at where Laurent was supposed to built. So I Googled it and look at the satellite photos and at a few images from the highway. It still looks exactly as Marvin Miller described it.

MILLER: It was farmland. It was just adjacent to the interstate. There was a pond there in the middle of the land and it was a parcel of three hundred eighty acres. We were going to start from scratch and build a whole new town right there on that land and it was a nice dream. And I think we need a new dream and a better one.

AA: The next thing we discussed was how long it would take to gain political representation in, say, Vermont or New Hampshire or maybe Maine.

AA: Marvin it sounds like you’re still making plans.

MILLER: (laughs). Perhaps.

AA: Marvin Miller says Laurent was a good first try. And maybe, he’ll try again.

MUSIC

MARY: That was Amanda Aronczyk. While Marvin Miller had a dream of creating a separate community for the deaf, there are others who long to get their hearing back. And it’s more and more possible to do that. There have been huge advances in treatments.

But at each step of the way, there’s been controversy. When cochlear implants were first made available 30 years ago, they were really divisive. Some people thought they’d never work. Some people thought they would ruin Deaf culture.

But they’ve changed lives. There are these videos on Youtube, so many of them now it’s basically its own genre. They’re called “activation videos.” It’s the moment when someone has their cochlear implant turned on for the very first time. There’s one of a teenager - a girl with a ponytail and braces. And you can see the moment when the implant is turned on - it’s the reaction on her face. She leans forward and hits a toy xylophone.

You can’t watch one of these videos and not cry. That’s what makes this complicated. The advances are amazing. But people choosing devices and treatments - it changes the Deaf community. Is deafness a disability? A medical condition? Or a culture, with its own language?

Tell us what you think about this episode at onlyhuman.org. And while you’re there, subscribe to the show to join our Listen Up! project.

A reminder: we’ve partnered with an app called Mimi that will test your hearing. A lot of you have already taken that test… Rebecca from New York City shared her results with us. She says she started losing her hearing as a teen. She avoids loud parties and bars. “It makes me feel like I’m the oldest 27 year old ever,” she says. “Thanks for covering this topic.”

Go to only human dot org to find out your hearing age. And play along with us next week, when we’re all going to work on becoming better listeners.

Only Human is a production of WNYC Studios. This episode was edited by Molly Messick. Our team includes Elaine Chen, Paige Cowett, Fred Mogul, and Kathryn Tam. Our technical director is Michael Raphael. Our executive producer is Leital Molad. Thanks also to Andy Lanset, Winn Periyasamy, and Lena Walker.

Special thanks to KSFY News in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and Rick Pickren, who performed that state’s song, “Hail, South Dakota.”

Jim Schachter is the Vice President for news at WNYC. And I’m Mary Harris. Talk to you next week.