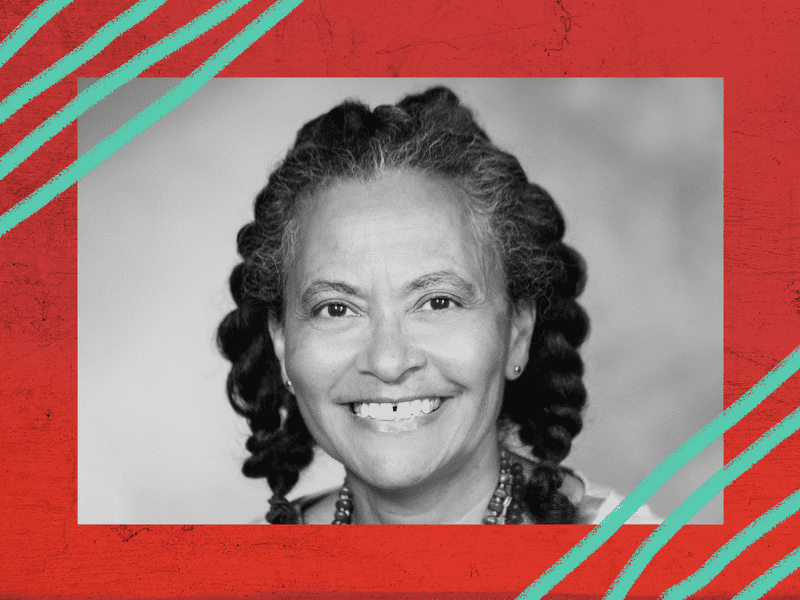

Dr. Camara Jones Saw the Tsunami

Rebecca: I’m Rebecca Carroll, and this is Come Through.

This podcast started out as a project focusing on 15 essential conversations about race in a pivotal year for America — an election year with especially high stakes. My producers and I began working on it a couple months ago and we were taping episodes with some amazing guests. Writers, activists, brilliant thinkers. The global pandemic hit. And things took a sudden turn.

Our lives and realities are shaken. And it feels like we’re being confronted by a moment that is hell-bent on putting America to the test. An era that is forcing us all to double down on the things we deem as being essentially American — freedom, health, happiness – and racism.

We know that it’s during times of crisis that racism really digs its heels in and reveals itself as the enduring, divisive and violent construct that it has always been. So that’s what we’re looking at.

Over the course of this series, I'll be talking with people from across the social and political spectrum about what's keeping them up at night: Bishop TD Jakes, who preaches to congregations around the world. Author Robin DiAngelo, who coined the term white fragility and is calling it out all across the country. Activist and organizer Brittany Packnett, AND Kay Oyegun, a writer on the TV show “This is Us” — all people who are wrestling with how their lives and work are shaped by race.

So I’m also making this show from New York City, the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the place where I’ve lived for nearly all of my adult life. And suddenly, we’re all working from home, and I’m conducting interviews from my husband’s sneaker closet.

I’m launching this podcast with an episode that’s raw, and urgent, and painfully real. Talking about race and racism is directly in my wheelhouse. Talking about a pandemic - is not.

This podcast is called Come Through, a concept that is about the ease and comfort of creating and maintaining conversation, especially within the black community. Now that we’re quarantined, how and where do we find that ease? That connection. That sense of home. What if we can’t? And then what will we do without it? What if it changes how we talk to each other? How we understand and love each other?

Maybe it already has changed the way we care and show up for each other. A day or so after the coronavirus outbreak was officially declared a pandemic, I called my friend Caryn. Because we’ve known each other for 25 years and her voice is very soothing to me. Because we were supposed to be leaving for vacation together with our families this week. Because she is my community, and because I’m feeling levels of worry I’ve never felt before.

Caryn and I are usually in touch on a daily basis— we know each other very well, but we know almost nothing for sure about this virus. So, how do we comfort each other?

Rebecca: So, um, first of all, how are you doing?

Caryn: I am well. I am well. And that was the question that now that we have this situation with this virus, it's like - what a loaded question? Because for most of our lives, people ask that question, and you just give them a quick answer. Now they ask that question. They really want to know a true answer.

Rebecca: Well, I mean, the other thing is that you and I, we check in a lot. I mean so…

Caryn: Right, right.

Rebecca: Now, it's sort of like, even with your closest people, it feels like it's changing on an hourly basis.

Caryn: Yeah, yeah.

Rebecca: And I'm struggling a little.

Caryn: Yeah, I know.

Rebecca: My son Kofi, and Caryn's son Anwar are just a year apart in age -- they're both teenagers.

Caryn: So, Anwar hasn't shown me any signs of freaking out. We've been talking about it. I want you to know that like my child and I haven't spent this quiet time together, as you know. Right? Usually this thing doesn't last for more than a couple, you know what - three days? Before there's like something to do. So, the fact that there's nothing on the calendar is such an odd new place, for Anwar and I.

That I'm very interested to see. I'm just kinda sitting back to see where are the places and spaces in a day where we actually seek each other out? Without telling someone what to do or needing someone to do something. Where you just literally do a touch point. Like yesterday I noticed, Anwar, I was walking past, and he said, mom, and I said, yes, and I poked in. He's like, I just want a hug.

Rebecca: Yes, absolutely.

Rebecca: Caryn and I moved to New York together in our early 20s. She knows my back story - that I was adopted by a white family, in a white community - and how lonely that felt.

Rebecca: it's like so heartbreaking to me that, you know, I grew up in a kind of isolation. Um, without my people. And then when I found my people, and chosen family of which you are, it's, you know, it just feels like it's so heavy. It's just so heavy.

Caryn: Yeah, it is. And it's, and think about it, it's like drawing that heavy curtain down at the end of the show. Right? And we are being asked to, citizens are being asked to pull that heavy curtain down on their neighbors, their elders, their little ones. Grandparents are being told to pull that heavy curtain down on their little ones. And it really begs the question: well, shit, if I have to not see my grandchildren for a month. I'm not sure if I'm not willing to take a little bit of a risk. If we're super careful, can we still hug? You know what I mean?

Rebecca: I totally know what you mean

Caryn: I think the United States is actually going to have a really hard time containing this, because we're so used to doing what we want, and we have very little faith in government.

Rebecca: Little faith in government, totally. But what about faith in our families and how we feel in our families, and how we are together.

Caryn: We still have to do. Rebecca, we still have to do. Right? So if you sent Kofi here, he's coming. There's no question If he’s coming. He's coming. There is no question.

[MUSIC]

Rebecca: Whatever comfort I thought I might be looking for when I called Caryn, I realized after we got off the phone that pretty much all I needed to hear was that if Kofi showed up on her doorstep, he’d be welcomed inside. Because in this time of crisis and the unknown, I find a small but potent mercy in knowing that my son has black family that will always embrace him, no matter what.

But even with that assurance, I still wanted to understand the pandemic and its immediate impact — is the situation entirely hopeless? What, if anything, can we do about it? So I called Dr. Camara Jones. She’s an epidemiologist and family physician, and the former president of the American Public Health Association. Dr. Jones has studied the intersection between race and medicine throughout her decades long career.

Dr. Jones: We see that racism has already made black folks sicker. We already see that resources have been taken out of our communities many times, and, and we don't have the same access. And now with this Coronavirus, even though it's making people pull together as a nation and as a community, I am afraid that the impacts of the virus is always going to be worse. You know, like when white folks get a cold, black folks get pneumonia. While I think it's going to be that in spades, unless we take special care. And the we that has to take special care, is of course individuals and families and communities. But we need to get through to policymakers.

Rebecca: So, I'm really, I'm super interested in looking at the pandemic through a nonwhite lens and specifically through the lens of a black woman, given the weight of what that intersectional identity means. What is your approach to the pandemic and what are you curious about? And do you feel like you're being heard and listened to.

Dr. Jones: Well, I'm grateful to you, for example, to reaching out to me. And others have reached out to me, and I'm also parts of collectives that are trying now to put out guidance. How can we have a health equity lens to our Covid 19 response?

And I know a lot of people hear the words health equity, and they're like, well, what is that? So health equity is basically making sure that everybody has the conditions for optimal health. Getting there requires at least three principles: valuing all individuals and populations equally, recognizing and rectifying historical injustices, and then providing resources according to need.

Rebecca: The first tenant, valuing populations equally - I mean, we know that that is not the case. We know that that is not in effect. And so how do we do that?

Dr. Jones: Well, so we, we do absolutely know that all people are not valued equally. How do we make it so? It’s through making it plain. So, it's through the naming racism. Then looking at mechanisms of decision making, who's at decision making tables, and who's not. What's on the agenda, and what's not. So that's about, uh, making sure that affected communities even now are at decision making tables when they're trying to figure out what to do. So let me get back to how it has already started. How this differential valuation, the fact that we're not valued equally is already manifesting here.

The first COVID 19 hospital that's going to be specifically for, uh, treating, isolating and treating people with COVID 19 and therefore not doing anything else that hospitals do, was named as Carney hospital, which is in the Dorchester neighborhood of Boston, which is a predominantly black neighborhood. That has two effects. It means that people will not be able to go to Carney Hospital for their heart attack or anything else, and it also means that there's going to be an influx of people who are infected with this virus right there in the middle of the neighborhood.

We need to stop being the sacrifice zones in this. So then how do we stop that from happening? We have to first of all say, this is not okay. We have to point out that it is happening again and we need to have people at those decision making tables who are going to either have those interests or be able to, at least in the short term, represent the interest of people who are, who are going to be differentially affected.

Rebecca: So the sacrifice zones are very real. Uh, and we've seen it throughout history. It's the theme of gentrification. It's the theme of Hurricane Katrina. It's, I mean, again, and again and again, but there's also, I don't know if you saw or are aware, you know. It wasn't until, the actor Idris Elba posted that he had tested positive for COVID 19 that folks on black Twitter were like: Oh, yo fam, we can get this.We can get this thing too, which is, which is so emblematic of who we are as a community, right? Because we're, we're skeptical of something that is positioned as effecting everybody because we're so used to everybody, meaning white folks.

Dr. Jones: So I think that's true. But yeah, fam, we need to, we need to know that we can get this.

And when we get it, we might get it harder. And the reason we might get it harder is first of all, because of the way that our neighborhoods have been structured by the federal government over decades and centuries, for example.

Then we have more crowded housing. We have less access to fresh fruits and vegetables, less green space and walking space. So, so therefore we have more diabetes, more heart disease, more kidney failure. But we have more of these diseases already, and we know that those diseases, irrespective of age - are making people get a more severe form of the disease because they affect our immune system. And we need the strongest immune system so we can fight off this virus. So we have to know, not only can we get it, but we can get it, and it might affect us more. So that means we have to be more serious. I'm not trying to say that we need to be living in fear, but we need to have some situational awareness - is what I call it. About social distancing.

I am in my house for the next three months - I'm prepared. You know, I've got some beans and some rice and some canned tuna, right? And I can live in here. No, for real. For real. Right? And I'm can live in here for the next three months. And the reason I'm doing that is because I'm 64 I'll be 65 next month - God willing, and my children texted me urgently on Monday - mom do not go outside. So, I am saying all the children listening to this, talk to your elders and tell them, do not go outside. Right? And then you have to realize, you also as children don't need to go outside. Right? You need to be not bringing the infection into people.

Right. But anyway, so we digress on that, but what I see – yes. We need to know we can get it.

Rebecca: I think that's really important too, though, what you're saying about your kids and generational roles. And you know, there's a lot of folks who have been talking about elders, you know, continuing to go to church, continuing to go to gatherings, you know, because that is sort of the core and the backbone of black community. So, what do we say to each other, when we do what makes us who we are?

Dr. Jones: I'm just going to give you a little example. So, my sister also lives up here in the Boston area. The Harvard Memorial Church has for two weeks already been online with its services and they put an online bulletin in the hymns, so you can sing along and the whole thing. Last weekend, my sister's church people were still up there, in the church building. So, that's not all right. And so, if the church isn't already online, then maybe the young people can help the church get online. Right?

Rebecca: So you had said that there's a moment of stepping up for young people, right?

Dr. Jones: There is. Young people have to realize that all of their actions are not just about them anymore.It's about their family, the community – it’s about this whole country, actually.

So young people, don't be like: “Oh, you know, I'm not worried about this.” You have to worry about it, not just for yourself, but for the elders, for the rest of the community, for the health care system. Because, at the point with those of us who are older like me, or have some underlying disease - even like HIV- we got more of that in our community. We got more of everything bad in our community, which is gonna put us at higher risk. When that happens, people be trying to get into the hospitals and trying to be careful in the intensive care units, and then that's - if we run out of ventilators in the intensive care units - then doctors are going to start making decisions.

Who gets this one ventilator? That one. Or that one? And they're gonna be using a few criteria so far. We need to work against this too, but they are going to use – age, where an older person may not get it, and they're going to use, do you have any other health conditions? Do you have heart disease? Do you have asthma, which we have more of in our community. Do you have kidney failure, which we have more of in our community. And they might, in Italy at least are saying, if you have those things, we're not going to try to save you. Now, I think that's the wrong criteria. But what we need to do as young people is make sure that that we aren't spreading the disease so much that then in, it peaks so fast that then our people are in the hospital needing those ventilators and might be getting turned down. Because they have other conditions.

In just a minute, Dr. Camara Jones on how to stay safe -- and keep your family safe too.

Rebecca: Today I woke up feeling kind of a - sense of grief? Like I'm grieving the loss of something? Like going through like a really difficult breakup? And I don't know what it is exactly, like losing a friend maybe? Or it's just, I guess it's a sense of grieving the loss of safety. Maybe.

Dr. Jones: Right. And grieving that this crisis might not be met in the best way, but might even be used as an opportunity for something really bad.

Rebecca: It’s Karma

Dr. Jones: Yes, that's my fear. Can I just give you an image that was with me? It was the way I was feeling all last week. So all last week, I was feeling like I lived on a seashore. I felt the earthquake. I knew the tsunami was coming, and yet I was standing there watching the children collecting shells and fish off the beach.

Rebecca: Wow.

Dr. Jones: It was sort of like how I felt the nation was dealing with this. Because we'd already seen China. We had already seen a better response in South Korea. We were seeing Italy. Which we are just 10 days behind Italy, right? And we weren't acting. The thing is we need to get to high ground.

We need to grab the children. Who may feel like they can swim, right? But we need grab, and get them high ground. But then I've been thinking also that high ground is not the same for everybody.I've even been thinking about people who now are able to work from home. Like I'm working from home, you know. And I have a base, and I'm still gonna get some kind of salary, at least through May. Okay? That's some kind of platform. I was connected, but there are many of us who were not connected to any kind of platform. Or if we were connected to a platform, it was a very tenuous connection. And this sea that we're finding ourselves in - this tsunami - is going to shake us off of that connection. And we're going to be drowning.

So, I think that some of the efforts that policy makers are making like: Families First and Coronavirus Response Act is about, you know, throwing little, little life flotation devices. Like you see in a pool. To people who've been shaken off of a tenuous connection to a platform.

They aren't even really getting to the people who had no platform in the first place. So, those people who are salaried, are going to have better survival than those who are not. Those people who have a job are going to be able to get unemployment or paid sick leave in relation to that job. And those people who do not have a job, are not - right? So that's already going to be differential.

All of those structures that we have are already operating against us getting resources to everybody equally.

Rebecca: I think one of the biggest things I'm struggling with is whether or not things will “be okay”. I have a teenage son and, that's the kind of thing that we tell our children a lot of the time - that things are going to be okay. But as parents of black children, specifically, there are occasions when that's just simply not the case. And you know, our children are at higher risk of being profiled by police, deprioritized in education and health, as you've mentioned. Are things going to be okay for our black children on the other side of this pandemic?

Dr. Jones: Only if there's political change, and only if there is a residual sense of - we are all in this together and there, but for the grace of God go I. So do I think we're going to have that change? I think this is an opportunity for us to try to do that. So, I am ever hopeful. I could not be working on racism if I were not hopeful. Right? Because why am I going to beat my head up against a wall when it seems like things can't change - and it's because I have the long view. But maybe we can foreshorten what I think is three generations - into this one generation.

Rebecca: What is it that’s getting you through?

Dr. Jones: My daughter, again who's 29, and lives in London, and is going through it over there, gave me the suggestion. That every morning I should journal, at least three pages. So, I started that this morning - and it was great! Then I told her, I said, “Kayla, I did it” and it was great! And she says, yes, it's magic. Because it helps your mental health and it also unleashes your creativity. What I'm going to be doing in these days is I'm going to be writing the books that I have been up here for months, as a Radcliffe fellow at Harvard, to write. But I've been easily distractible, and I've been going to this and that and you know. And I haven't sat down to write. So, I'm going to write these books.But that thing of journaling every day, we text between us. All the family; my sister in Cincinnati, my sister here in Boston, but far away, my husband in Atlanta, my son in San Francisco, my daughter in London. Each of us makes sure that the other one is okay. You know, cousins like - talking to people I haven't talked to in years. So everybody's checking in on everybody else.

Rebecca: And still in community.

Dr. Jones: And still in community.

I don't even know what I'm going to do to exercise. Cause that's going to be an important thing too! We have to keep our spirits strong, and our body strong. And so I don't know what I'm going to do? Is it can be jumping Jackson, the apartment…

Rebecca: Are you really, literally, not leaving at all?

Dr. Jones: I am literally not leaving at all, until I have to. Because I am 64, almost 65. I had a breast cancer diagnosis last year. I am in the high risk group.

Rebecca: Sorry to hear that.

Dr. Jones: Yeah, I'm good. I claimed the cure. But I am in the high-risk group. I am not going out, at all. No, I am not.

Rebecca: Well, I am so grateful for your clarity. And for your ease and faith in us. Not just as black folks, but as a country. And I feel so much respect and gratitude for what you do. So, thank you.

Dr. Jones: Oh, thank you. Thank you for what you do.

That was Dr. Camara Jones. And earlier in the show, my friend Caryn Rivers.

Come Through is a production of WNYC Studios.

Christina Djossa and Joanna Solotaroff produce the show, with editing by Anna Holmes and Jenny Lawton. The show is executive produced by Paula Szuchman. Our technical director is Joe Plourde, and the music is by Isaac Jones. Special thanks to Anthony Bansie.

I’m Rebecca Carroll - you can follow me @Rebel19 for all things Come Through - and, this is one of our very first episodes - if you liked it - please share, review and rate us. Thanks - until next time – take care.