How a Prenatal Test Is Transforming Modern Medicine

( SMC Images / Getty )

Mary Harris: You can tell how tough pioneering biologist Lee Herzenberg is when she talks about the birth of her third child, Michael.

Lee Herzenberg: it was a little bit painful – but that you forget very quickly – and it was just really good.

MH: Her obstetrician was a friend, actually.

LH: The doctor was a woman, she was a really wonderful woman and we just had a very good time having this baby. It was just, it was cool very, very cool that birth.

MH: Was anyone with you during the birth?

LH: No (laughing) You weren’t allowed in there, not at that time! Fathers stayed outside – this was like an operating room!

MH: This was 1961. Lee had just moved to Stanford with her husband, Len. Len was a biologist, too. Lee was working in his lab while raising their kids. Michael was their first boy. But as soon as he was born, things started going wrong.

LH: and before we got through the door – one of the nurses noticed Michael was cyanotic...

MH: What does that mean?

LH: Means he’s turning blue – which means he wasn’t getting enough oxygen - so they took him very quickly into the nursery.

MH: Back then, there weren’t any ultrasounds or prenatal tests. Women like Lee simply spent nine months anticipating a child, and hoping for the best. And Lee noticed right away that Michael did not look like her other kids.

LH: And then nobody came around for several hours – and I couldn’t figure out - when am I going to see this baby? This crazy new practice in this hospital, they don’t let you see your baby?

MH: Michael had eyes that slanted up, and a flattened head - all the characteristic features of Down Syndrome. The doctors couldn’t decide what to tell her, so they told Len instead.

LH: and then Len came up and told me. That brings emotions back – anyway –

LH: the baby was lost. We hugged each other and it was a terrible conversation to realize that you’d lost the baby. So but we knew immediately what we’d do – we had already made the decision that it was not a good thing to take the baby home, and so we didn’t.

MH: So you’d already made the decision – like beforehand if something was wrong we’ll wouldn’t

LH: We hadn’t thought about it – but they believed he’d die within first 2-3 months.

MH: But Michael -- wasn’t lost.

I’m Mary Harris, and this is Only Human. After Michael's birth, his parents dreamed of a simple blood test to screen every pregnant woman for Down Syndrome. Now, that test is a reality. For parents, it means making tough choices about whether babies like Michael will be born at all.

Lee Herzenberg is 81 now. Her husband Len died three years ago. She’s still running the same Stanford lab she was working in when Michael was born. Before she had any of her kids, she knew she had ambitions beyond motherhood. And her husband made that possible. They met in 1951 at Brooklyn College.

LH: He was a senior, I was an entering freshman. And we both belonged to a club - that was called the society of biology and medicine.

MH: Did you know you were going t o be a scientist?

LH: No! I knew I was going to be something, but I wasn’t quite sure... The one thing I was not going to be was a gum chewing socks knitting freshman at the college, that I knew I was not going to be.

MH: They got married when Lee was just 18. She moved with Len to Cal Tech, where he was getting his PhD.

But Lee was ambitious.

Even though women weren’t technically allowed to attend Cal Tech, she started auditing courses. At night, she worked with Len in the lab.

When they had children, Lee would simply bring them into the lab and keep running experiments. By the time they got to Stanford, they had two daughters.

But when Michael was born - he had some of the worst physical complications of Down Syndrome. So they never even brought him home.

LH: He probably would have died in my hands.

MH: You think that?

LH: Yeah i do - he had the heart problem, stopped breathing several times - there was just no way that i could see that i could put that incredible amount of energy into the child knowing that he was compromised.

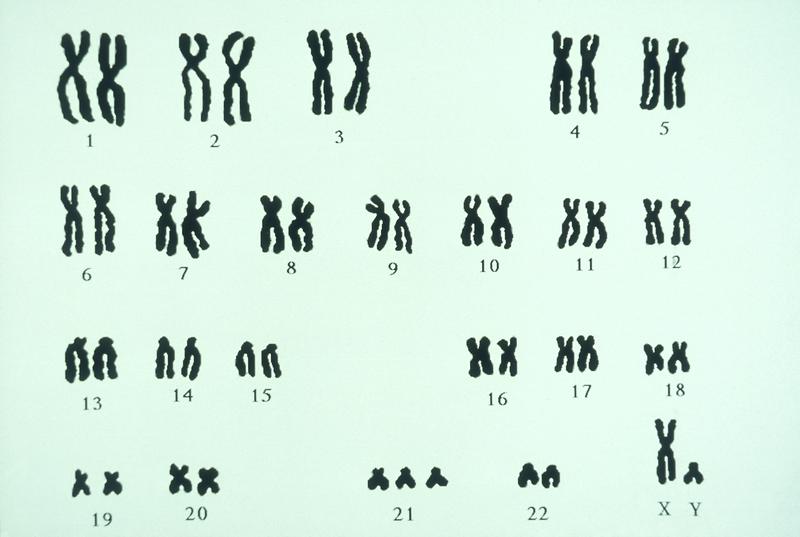

MH: At the time, doctors didn’t understand much about babies with Down Syndrome. It was only a couple of years earlier that a French researcher had discovered the biological cause — an extra copy of chromosome 21.

LH: My grandmother was staying with me and my // grandmother was convinced – that all we had to do was take this baby home he was going to be ok – and we couldn’t explain to her this is a chromosomal abnormality grandma, you don’t get over this. (laughs)

MH: So their pediatrician helped them find a local woman to care for Michael.

LH: My life was really working in the lab by then // our life is emotionally committed to science. So we understand this. It’s part of how we make our decisions // and I just knew that - I would give this up and this would be for no good reason because I could never make this baby normal

MH: It sounds like a pragmatism that very few people have

LH: It’s a gift to be doing science – it really is. It’s a gift to understand the physical and the biological world.

…

MH: OK, show me around!

MH: The search for a blood test for Down Syndrome started when the Herzenbergs invented a machine that changed medicine.

Catherine: So this is one of our sorter suites…

MH: I visited Lee’s basement offices, and asked a lab director to show me around.

C: I’m going to start a side stream so you can see what this baby does

MH: This machine is called a flow cytometer, or a FACS. Some people call it the first biotech device.

MH: When it’s all closed up it really does look like a little printer or something and then you open it up and it’s like seeing the magic inside.

C: That’s exactly right. And it really, truly is magic.

MH: Before this machine existed, finding a cell on a slide was like - well imagine “Where’s Waldo” - but the page is ten times bigger, and Waldo is ten times smaller. It took hours staring down a microscope.

Now, you literally pour cells into this machine and then those cells get separated and sorted.

MH: so then you get a big bucket of t-cells?

then you get a big bucket of those cells that has some specific signature that you’re interested in studying

MH: It takes seconds.

C: Just the fact that you can separate them is really the magic.

MH: The FACS can count up T-Cells and diagnose AIDS. And it’s been crucial in finding stem cells.

But in 1975, the Herzenbergs were still trying to prove how important this machine could be. They saw an opportunity in what seemed to be an outlandish claim by another researcher.

He said he’d found cells from a baby -- fetal cells -- in a pregnant woman’s blood. Nobody believed him.

But Len thought maybe he’s right. Let’s put that blood in the FACS - and sort those cells out. Because once you have those fetal cells, you can understand a lot.

Including, whether that fetus has Down Syndrome.

DB: They had a very personal reason for doing this, because of their son, Michael...

MH: Diana Bianchi was a student working in the Herzenberg lab at the time. Len Herzenberg made developing this test her project.

DB: And they wanted to have a test that could be offered to any pregnant woman – that would be non invasive and that would allow them to know if their child had down syndrome. The first step, however, was to show that you could pull out fetal cells.

MH: They needed blood samples…

DB: So as a medical student of course – I was the lowest person on totem pole so I was sent out to various people’s houses actually to draw blood on the mother and the father

MH: They were looking for couples where the father had a kind of marker -- a protein -- on the surface of his cells...and the mother -- didn’t. That way, if they found the protein on a cell in the mother’s blood, they’d know it had to come from the baby.

DB: So they literally sent me out driving all around the Bay Area with my blood drawing equipment – and it was good experience as a medical student because more than one father fainted in his own home

MH: Scientists now estimate that for every 200 billion cells in a mother’s bloodstream - only about 10 of those are fetal cells. Diana Bianchi was one of the first people to see them.

DB: It was really in the analysis of the data when we realized, yes, we were physically isolating fetal cells, the intact fetal cells from maternal blood

MH: At the time Len was quoted saying your work was a first step towards a blood test all pregnant women might get. Did you feel like that? Did it feel like this might be around the corner?

DB: No. (laughs)

MH: It would take almost thirty years for this test to become a reality. When we come back: the massive amount of genetic information parents are now getting. And the life and death decisions they’re confronting because of it.

MH: You’re listening to Only Human, I’m Mary Harris.

To understand why this blood test the Herzenbergs were dreaming of would be so transformative, think about how vulnerable it can feel to be growing a tiny human.

Fifty years ago, Lee knew nothing about Michael before he was born.

But even eight years ago, when I was pregnant with my first child, figuring out my risk for Down Syndrome seemed almost like witchcraft. First, I got an ultrasound to measure the baby’s neck. Then I got a blood test to check my hormone levels. A month after that, I got another round of blood tests.

Then, I was told my risk of having a baby with Down Syndrome was something like “1 in 100,000.” Which sounded great. But if I wanted to know anything definitive, I needed to biopsy the placenta, or take a sample of the amniotic fluid.

So, when Diana Bianchi found those fetal cells in a mother’s blood, back in the ‘70s - she knew - this could be a first step towards ending all that. And she kept working at it for decades.

MH: when did it become clear to you - oh! this is m y lifes work?

DB: That’s something I think about a lot – // why didn’t I give it up? There were a lot of frustrations along the way...

MH: Including this one: there just weren’t that many fetal cells floating around, remember it was just 10 for every 200 billion.

But there was something else - little tiny fragments of fetal DNA just floating around in the mother’s plasma. A lot of it.

And as mapping the genome got cheaper and cheaper, a few labs were able to --

DB: develop a sophisticated molecular counting technique.

MH: It works like this: a fetus with Down Syndrome has an extra copy of chromosome 21. So if a pregnant woman has more DNA coming from chromosome 21 then she should - her fetus is probably affected.

DB: And that was the ah-ha moment; that was the breakthrough

MH: This breakthrough moment happened in 2008. The first researcher who made this discovery sent his work to Lee and Len. And Len made sure it was published. Three years after that, the tests were on the market.

DB: At the end of the day it’s hard to think of another test that’s used in medicine that has been incorporated so rapidly into care and has totally transformed prenatal screening and diagnosis worldwide.

MH: I know this first hand. When I got pregnant a second time, the prenatal screening process was totally different. At 10 weeks, I gave a blood sample. And a few days later, I got this call. My risk for Down Syndrome was “low” -- really low. As in - virtually none. No ultrasounds, no odds ratios.

But having this kind of information, so easily, and so early on, alarms some parents.

KK: How was school today, honey? Good!

MH: This is Kurt Kondrich. His daughter Chloe is thirteen. And she has Down Syndrome. But unlike Michael, she’s being raised at home.

(sound of Donna Summer’s “On the Radio”)

KK: You want something to eat?

CK: Yup

KK: What do you want to eat?

CK: Chicken, applesauce and milk.

KK: What kind of milk do you want?

CK: Chocolate.

MH: Intense therapy from an early age has had a huge impact on Chloe. She’s reading at grade level. She plays on a baseball team. And when we visited her home in Pittsburgh, she was getting ready to go see her big brother Nolan play volleyball.

KK: The manager of the volleyball team is a high school student. What does Brendan have?

CK: Down Syndrome.

KK: Down Syndrome. So what did Jesus make him?

CK: Perfect.

KK: That’s right.

MH: Kurt Kondrich is a religious guy. He is pro life. But he says that like Lee and Len Herzenberg, he’s also pro-information

KK: I call myself a Dad-vocate --

MH: And when he started meeting other parents of kids with Down Syndrome --

KK: I didn’t run into one family that was told anything positive about the prenatal test. I’d say what happened after you got the diagnosis and they’d say well we were basically told to terminate the child.

MH: And that made him frustrated -- so frustrated he started driving to the statehouse in Harrisburg - that’s a three hour drive, each way - just to pass out information about kids like Chloe.

And then, he went even further. He worked with legislators to pass a law that mandates the kind of information you can be given when you’re given a prenatal diagnosis. The law is actually named after Chloe. Now, parents in Pennsylvania get this fact sheet. It doesn’t mention abortion. But it does mention support services for kids with Down Syndrome.

KK: Nobody was being given facts. They were just told to terminate the child. If you had a daughter that had brown hair & brown eyes and prenatally they were able to screen & determine that & the culture decided that everyone should have blond hair & blue eyes & they were telling you to get rid of your daughter and you knew -- wait a second, my daughter’s cool! You gotta meet her. She’s really neat. That was me. I want you to meet my daughter, see how cool she is, I want you to see the impact she’s having on this community.

MH: As non invasive Down Syndrome screening has become more accessible, advocates like Kurt Kondrich have helped laws like this one spread to other states. And North Dakota and Indiana now explicitly ban abortion if Down Syndrome is the reason.

MH: You had Chloe before these blood tests became available that would screen for Down Syndrome prenatally. Do you feel like your work took on more urgency after those tests became available?

KK: Yes I do because I want Chloe to have peers… I want her to, you know. By not giving the facts out about these children, what we’ve done is -- I’ll just say it, it’s silent eugenics. You’re identifying, targeting and eliminating a group of people based on misinformation and based on what you perceive as a mandated perfection.

MH: The word “eugenics” sounds kind of extreme. But Kurt Kondrich has a point -- prenatal information lets parents decide if they want to keep or terminate a pregnancy.

Diana Bianchi, that researcher who helped start the hunt for this test, is trying to figure out whether Kurt’s fears are justified.

MH: What do you say to people who worry about the kinds of information that can be found with these tests?

DB: Not everybody who finds out that their fetus has Down Syndrome aborts and I think that’s extremely important.

MH: Do you think that’s misunderstood?

DB: It’s a very politically charged issue…

MH: There’s this statistic you’ll hear quoted sometimes - that 90% of parents who find out that their fetus has Down Syndrome, will abort. But that statistic is from a study done in the United Kingdom. In the US?

DB: We have good data to suggest that approximately 40 plus percent of women who know their fetus has Down Syndrome continue their pregnancy. There are many women who speak very highly of the fact that this allows them to prepare.

MH: And Diana Bianchi is hoping her latest research will help parents prepare even more.

DB: You know - we have to unpack this connection between prenatal testing and abortion, and that’s important because a large part of our lab is focused on developing prenatal treatment for Down Syndrome.

MH: Prenatal Treatment for Down Syndrome. Her new goal sounds kind of wild. But she says it makes perfect sense. Because now, there is this critical window -- you get your blood test results at 10 weeks, but -- with Down Syndrome --

DB: You begin to recognize the differences in the size and the shape of the brain around 16 weeks.

MH: So, theoretically, you could treat fetuses before some brain damage happens at all.

She’s testing drugs that could help protect the brain from what’s called “oxidative stress.” It’s research that is at its very earliest phase - mouse trials. But the drugs she’s testing are all FDA approved. And her goal is to move to humans as soon as possible.

DB: It’s somewhat frustrating as a physician if you have information and you’re not able to help the patient at all. Great you made the diagnosis but what are your options. So it’s much more exciting if you are able to say to a pregnant woman we made the diagnosis and now you have a potential therapeutic option.

MH: But it’s hard for these therapeutic options to keep up with the massive list of conditions mothers are getting testing for. Because it’s not just Down Syndrome anymore. Now, this test screens for a baby’s gender - and all kinds of chromosomal abnormalities.

As I was getting ready to leave her office, Diana Bianchi told me we need to talk more about the implications of these prenatal tests. She singles out one testing company in particular --

DB: So they’re looking across the genome, and reporting on any variation that’s either too much or too little.

MH: If it’s too much or too little, right, what does it mean?

DrB: We don’t know. It hasn’t really been fully evaluated….

MH: She says, take, for example, an extra copy of chromosome 16, called a trisomy.

DB: If you screened positive for trisomy 16, you probably are going to miscarry the pregnancy. Or you’re at high risk for fetal growth restriction.

MH: Some children with abnormalities in chromosome 16 are just a little bit small. Others need intense care. And now parents have to decide: how much do we want to know? And what are we going to do about it?

…

MH: Michael Herzenberg -- the Down Syndrome baby who helped start this search -- is 54 years old now.

LH: It’s this one

MH: the white one...

MH: I asked Lee Herzenberg, to take me to visit her son. In the car, we get lost on the side streets of Redwood City, California.

LH: Let’s hope we have the right house.

MH: So we walk into the squat one story house that he shares with five other adults with developmental challenges. Lee doesn’t get the chance to come here very often.

LH: Hi Sweetheart. You have a big kiss for me, hm?

MH: When Michael was growing up, his parents would visit him every month or two. But they never thought about bringing him home. Lee says she wouldn’t have wanted to take him away from his adopted mother, Barbara, who died a few years ago.

Michael has brown hair and a high voice.

Michael: Me and J on TV pretty soon?

MH: Tell me again?

MH: It’s hard to tell how much he understands.

MH: How old are you?

Michael: 11 2 61

MH: I don’t understand.

MH: It takes a couple of minutes to figure out that when I ask how old he is, Michael is answering by giving me his birthday.

But it’s clear that he loves getting a chance to see his mother.

MH: So you have so many pictures here, you have a lot of pictures of your dad…

MH: Michael’s room is covered in photographs of family - his birth family and the people he grew up with.

Michael: Pat, Joey, Mary, Steve...

In one corner is a big poster of Len Herzenberg, from when he won the Kyoto Prize -- which is sort of like Japan’s version of the Nobel Prize -- for his contributions to biotechnology. Michael goes into photo albums to show me pictures of the woman who raised him.

He calls her “lambie.”

LH: Who’s that?

Michael: A cousin. Rainey and Janine.

LH: That’s Rainey, yes.

LH: There’s a picture of your Lambie.

MH: He actually says he has two “lambies.” The woman who cared for him growing up, and the woman who gave birth to him.

LH: Yeah and you’re dad….

MH: I must have asked Lee five different ways if she ever regretted giving Michael to another family. She says she doesn’t. But I asked one more time, before I left.

MH: I know some of the people who hear this - they’re just not going to understand the decision that you made not to raise Michael - I just wonder what you would say to them?

LH: That’s an interesting question -I don’t really know it’s - it’s selfish if you like, because we had things we wanted to do. In retrospect - a lot of things would never have gotten done - there would be no FACS had we decided to do this. Because it would have been a very intensive kind of upbringing. But, on the other hand, he wasn’t being put in a cot in an institute. And I was thrilled to have someone share my child with me. And so - it seems like a hard-hearted decision - you say OK I’m not going to take this child home - but it wasn’t that.

MH: These decisions are so personal. Lee is thrilled that the Down Syndrome test she and Len first dreamed up decades ago eventually became a reality. But what information is important to an expectant parent depends ...on the parent. So for Lee, who fought so hard to build a career, screening for a disability isn’t upsetting at all. But --

LH: Suppose everybody just did their prenatal diagnosis and told whether they were carrying a boy or a girl?

MH: That’s exactly what happens right now.

LH: That’s right, it is done and inappropriate. //

MH: Lee’s fears aren’t unjustified. There are reports of women in China using these blood tests to screen for gender, and terminating if the baby is a girl.

MH: But here are people who see detecting chromosomal abnormalities as the same thing?

LH: No I don’t see how.

MH: But if Lee had the choices women have now, she might have chosen differently, too.

LH:I see no reason why Michael has to live the life that he leads. The fact that we made it very happy for him or he’s made it very happy for us– all of that’s adapting to a situation but I don’t really, I just don’t think it’s fair or proper. // Truly I would say if I had the choice of not pushing Michael into this life, if I at that point would known I – I would have aborted the child.

MH: When I talked to Kurt Kondrich, the dad-vocate from Pennsylvania, I asked him about parents who feel they just can’t handle a child with special needs. He said -

KK: All of us are one accident, one illness, one mishap away from becoming completely disabled. If you live long enough, someone’s going to change your diapers again. So how you support people who are vulnerable and at risk, all people, will reflect on you, who you are in your soul, as a culture.

MH: When I was pregnant, I remember wondering what I would do if that test for Down Syndrome came back positive.

And as I thought about it, it seemed to me that having a diagnosis isn't the same as knowing how that diagnosis was gonna affect me.

Down Syndrome makes expecting parents really nervous, but there’s good data showing families who raise these kids are pretty happy, long term. Maybe happier than parents of kids with issues we can’t screen for at all.

And I wonder if all this testing isn’t just trying to make us feel more certain about one of the most uncertain things in life.

Because that baby you’ll fantasize you’ll get when you’re pregnant -- no one gets that baby. No one.

Some parents just realize it a little bit earlier.

If you have a story you want to share about an experience with Down syndrome, we’d love to hear about it. Write us at onlyhuman@wnyc.org.

CREDITS

This episode was produced with help from Jillian Weinberger and edited by Ben Adair.

Only Human is a production of WNYC Studios. Our team includes Amanda Aronczyk, Elaine Chen, Paige Cowett, Julia Longoria, Kenny Malone, Fred Mogul, Ankita Rao, and Ariana Tobin. Our technical director is Michael Raphael. Our executive producer is Leital Molad. Thanks also to Megan Cunane and Eleni Murphy.

Jim Schachter is the Vice President for news at WNYC.

I’m Mary Harris. Talk to you next week.