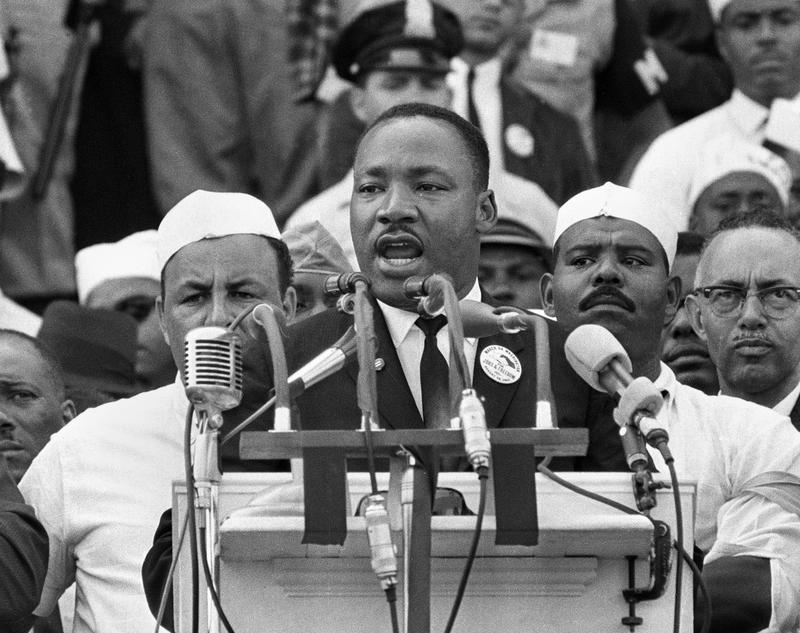

Do We Understand The Full Breadth of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s Message?

( Uncredited / AP Photo )

[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: I'm Melissa Harris-Perry, this is The Takeaway. In 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed Public Law 98144, designating the third Monday in January as an annual federal holiday to honor the life and work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The President's signature was the final step in a journey that began in 1968, shortly after James Earl Ray assassinated Dr. King in Memphis, Tennessee. Civil rights activist led by King's widow, Coretta Scott King, began fighting for official recognition of his work and contributions to the American project.

The journey to the holiday was fraught with racial and partisan tension. Nearly four decades after the holiday was established, we continue to have a complicated relationship with the memory and legacy of Dr. King. Far too often lesson plans and public observances of King Day are limited to recitation of a few words from a single speech delivered in 1963.

Martin Luther King: I have a dream.

Melissa Harris-Perry: The King we recreate with our limited interpretation is solitary and frozen. His words are inspirational and symbolic. This King is safe. The living King did not stand alone, he was embedded in community. His vision for racial justice was not simple and fixed, it was complex and dynamic. His words and voice were important tools but represented only one part of an evolving strategy. The living King was not safe, he was dangerous, a threat so formidable he was subjected to surveillance, violence, and ultimately, assassination.

Melissa Harris-Perry: With me now is Scott Roberts, Senior Director of Criminal Justice and Democracy Campaigns for Color of Change. Scott, welcome back.

Scott Roberts: Thanks for having me.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Here also is Patrisse Cullors, New York Times bestselling author, educator, artist, and abolitionists. She's also the co-founder and former executive director of the Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation. Patrisse, always great to talk with you.

Patrisse Cullors: Oh, so good to be here. Thank you so much.

Melissa Harris-Perry: All right. Patrisse, I actually want to start with you. Help us to understand some of the ways that mainstream narratives about King misrepresent who he was and what he could potentially represent to next generations of activists.

Patrisse Cullors: Well, it's important for people to understand that King was challenging white supremacy. In that, he was challenging how the world viewed society and was often a target of misinformation, disinformation was often a target. Often he was receiving death threats, he was receiving so much vitriol on a daily basis. I think in the age of King, if there were social media, he would obviously be the target of bullying, and bots, and social media trolls.

Melissa Harris-Perry: I so appreciate that. Scott, I want to come to you because I think there is this, oh, of the many misrepresentations, one that I dislike and most galls me is this notion that King was safe, Malcolm X was dangerous, and so King was celebrated. I keep thinking, do you not know what actually happened with King around surveillance and violence and ultimately, assassination? I'm wondering why in our remembering of King, we so frequently write out just how dangerous to the status quo he and the movement he was part of really were?

Scott Roberts: I think it's because, for the last 50 plus years, Dr. King's legacy has been really contested. There's been a battle over what he stood for, what he did, how he helped to accomplish the things that he did. There's a version of Dr. King presented [unintelligible 00:04:12] by the right of colorblindness, that one quote from his speech, that he wants his children to live in a society where they're not judged by the color of their skin, but the content of the character, is turned into a whole--

Some of his beliefs and ideology versus the real Dr. King, which was a man pushing for voting rights. Also, there's this portrait of him tactically, I think that's really important, the idea that Dr. King, though the focus on non-violence, as opposed to looking at how confrontational the actions and tactics that he employed were.

I think, Ava DuVernay who obviously is one of the real leaders in terms of portraying Black folks but also leading on racial justice issues and Hollywood did a good service with the movie Selma, to show how confrontational and radically was to do that and the resistance that he got even within his own movement there. I think there's been this struggle over his legacy. Even, one of the things that used to annoy me the most on the Martin Luther King Day during the Obama administration, was the email that you would get telling you to go into a community service action.

I think, even within the Democratic coalition, there's a contest over whether Dr. King's legacy is one pushing for radical and transformative change versus doing right by your neighbor, which obviously is a part of what he had to say when I think it's frustrating when it's reduced to that.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Patrisse, on that kind of reductionism, even this notion that we should keep looking back and say, "What would Martin Luther King do? What would Martin Luther King say?" How as an inheritor of the work for justice, do you think about King within the context of your own work?

Patrisse Cullors: I really see King as not just someone who was working on domestic issues, but honestly a leader that was looKing at the international politics of his time. He was really challenging the war, he was challenging imperialism, he was challenging capitalism. That is often so left out of his legacy, but so critical for us to understand. What we have inherited as movement leaders, as people who are challenging capitalism and challenging the role the US government has played, not just here in the country, in the US, but also around the world.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Scott, let me come to you because you were talking about strategy before the break. I want to think around the strategy piece because there are ways that we can look to Dr. King's strategy, his understanding of himself, his use of media. There were also real challenges with his strategy, maybe specifically the lack of intersectionality. Maybe you could speak a bit around how today's movements, how the work that you're doing at Color of Change is seeKing to in part be a corrective around gender and queer identity and other intersections of racial struggle.

Scott Roberts: One was just the centering of Dr. King within our movements, is important and critical as he was to the advancement of racial justice is in itself, just focuses attention once again on a cisgender straight man, but also the politics of the time. We just think about the posters of the marches when folks are carrying signs, "I am a man," just erasing the women and non-gender conforming folks in the Black community.

You see this. If you read up on the stories of Dr. King's relationship with Bayard Rustin, and the way that Bayard Rustin was a brilliant strategist, really behind a lot of the best work that Dr. King did, as a gay man was forced to work in the shadows and eventually pushed away from the inner circle of Dr. King. I think today's movement and I would credit people like Patrisse far more than myself and Color of Change for this.

Organizations like the Black Youth Project and Black Lives Matter, so many other groups around the country, young people who have really pushed back against those oversimplifications, I think there's a need. We're seeing more and more leadership today, I think from women, from queer folks in our movement and that's critical. I think we also have to-- I think even myself, I can speak from my perspective, as a straight cisgender man who has been in his work, tried to take a backseat in a lot of situations, and push for leadership, and create the spaces and the room for folks to speak. With that, I think, I'd love to hear Patrisse's thoughts on this myself.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Absolutely. That's exactly where I was going to come to hear Patrisse's, is to reflect a bit on how Dr. King's sometimes problematic legacy around issues of gender and queer identity, as well as others, class was part of all of that, influence that building on King but also diverting from him.

Patrisse Cullors: The biggest moment for us, especially as folks who have taken on his legacy, is to both understand it as something that we are inheriting, but also understand it as something that we are challenging. Many of us movement leaders who are Black women queer, understood that while King challenged white supremacy, he didn't challenge patriarchy and that's not something to look back at and completely judge him on, but it is to look back say, hey, this is something we want to do different in this generation. I do also want to say that, King was someone who was really evolving in his understanding and of his role and the role of the US, and the role of the police and the military.

So much of what gets lost in his legacy and his current legacy is this conversation about how he challenged the military, how he challenged the police. I think that's so important because so much of this generation is pushing back and challenging policing and the military and imprisonment as we know it.

Melissa Harris-Perry: It seems hard, but the truth, would you imagine that someone misses that King is challenging policing? In fact, again, if we're thinking about some of those misrepresentations, it's sometimes that notion of, as Scott was saying earlier, of a non-violent social movement, rather than reflecting that the movement was quite violent. It was provocative of violence, provocative of police violence as a way of demonstrating, of laying bare what the state had done as a matter of violence over and against Black bodies.

Patrisse Cullors: There's a quote that I wanted to read to y'all, which is, King, said, "A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than programs of social uplift, is approaching spiritual death." That feels critical to me because, if we think about this movement to defund the police, to abolish the police, I wholeheartedly believe that King would be a part of that movement. He would be saying, "Hey, you guys, we are spending way too much money on the military, way too much money on the police, and there's no social welfare institution in this country anymore."

We see that right now in the middle of COVID, while we're watching this pandemic rage on and having this medical, industrial complex that is so unable to really fit the bill in this moment, I think King would be challenging all these things right now.

Melissa Harris-Perry: I wonder Scott, to Patrisse's point about, where King would be, what he would be challenging. It seems to me that undoubtedly would have to do with what relationships, what community he found himself in. That he was always responding to and part of a broader conversation and yet when we represent him, when we think about him on King day, he does end up almost like the monument of him in DC. Like it's just him carving out of mountain as though he's not from community.

Scott Roberts: I was hoping to get a chance to talk about this. I think one of the challenges of the way in which Dr. King's legacy has been contested and the way he's been portrayed has as I think I said earlier, taken about an outsized portion of the history of the movement. A lot of times we miss not only the folks who were behind the scenes working with King, like Bayard Rustin, who I mentioned earlier, but also the broad range of organizations and tactics that were being implemented.

I mentioned Selma earlier, even in the arguments there, you didn't actually see for instance, in John Lewis' story arc, where he had the tensions with SNCC. You didn't actually see the work and the tactics that SNCC had been doing just the summer before in Mississippi in the Mississippi Summer Project, which a lot of folks now will refer to as Freedom Summer, which was not a bunch of marches and not violent actions, it was people on the ground, organizing door to door, registering people to vote which engendered the same types of violence and also captured the nation's attention and shifted a lot of hearts and minds on the issue of voting rights.

I think I would encourage people this MLK Day to try to dig in and learn more about the broad range of tactics because I think it would help people put today's movement more in perspective and help us move beyond this notion of who's right, who's wrong, which is the right thing to do and not-- and understand in a movement where there's going to be a diversity of approaches and we have to have that in order to advance things.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Scott Roberts, Senior Director of Criminal Justice and Democracy Campaigns for Color of Change and Patrisse Cullors, New York Times bestselling author, educator, artist, and abolitionists. Thank you both for joining us today.

Patrisse Cullors: Oh, thank you so much for having us.

Scott Roberts: Thank you.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.