BROOKE: Conventional wisdom says that new media have ushered in a new kind of journalism. And the fact is, despite all the conferences and anxious op-eds, we really don't know where we're going. Veteran journalist, educator and historian Loren Ghiglione was tasked with writing about the future of journalism. And his search for answers to him pulled him in an an unusual, though perhaps inevitable, direction. He immersed himself in a genre he'd always disdained, science fiction, also known as speculative fiction. When we spoke with him a few years back, he had found that when authors imagine with reckless abandon, their predictive powers often outshine the experts...

GHIGLIONE: I mean, this started for me when I was guest curator for a Library of Congress [exhibit] on the History of the American Journalist. And the Library said the last chapter must be [LAUGHS] on the future. And I started reading futurists, and then I started reading [LAUGHING] science fiction writers. I decided that the science fiction writers probably were more worth reading than the futurists.

BROOKE Because, as you quote Ben Bova observing in your piece, “Futurists could not have predicted the transistor because there wasn't any science to underlie it back in the early days of the last century.”

GHIGLIONE: Right.

BROOKE: But speculative fiction writers, science fiction writers, did. They predicted miniaturization all over the place because they just assumed it was going to happen, eventually.

GHIGLIONE: Exactly.

BROOKE: So let's talk about how speculative fiction has treated the news media. French writers distinguished themselves early, beginning with Emile Souvestre in 1846?

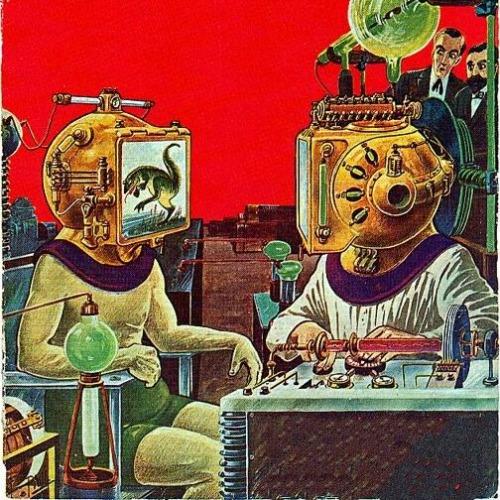

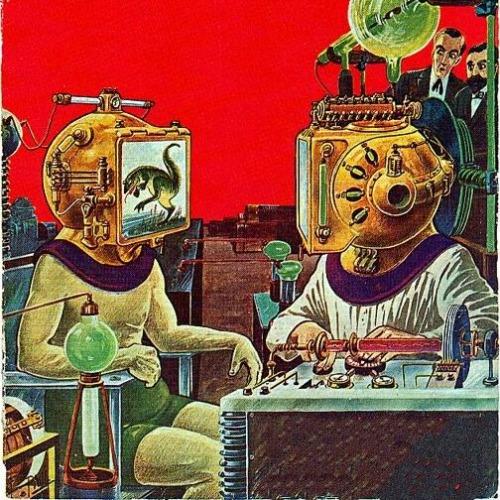

GHIGLIONE: Yes well, they extrapolated from the newspapers of the day to have a, a newspaper that would be one large spool of newsprint with type on it, running through a village and going up to the third floor apartment and down to the street, and people would read this moving roll of newspaper. But they also anticipated, more dramatically, news on television and interactivity.

BROOKE: We should stipulate this is fully 100 years before television.

GHIGLIONE: Exactly right. And the illustrations in the novel show people looking at a screen in their homes.

BROOKE: Albert Robida wrote The Twentieth Century in 1887. What was his vision?

GHIGLIONE: He’s the one who had the all-electric home with telephonographics, news bulletins delivered automatically through telephones, and he had wall-sized telephonoscopes, which were televisions – [BROOKE LAUGHS] - that were interactive so people could react to the news and communicate with other people who were seeing the news. And -

BROOKE: What a bizarre idea! Now, if we get to the American midcentury, we inevitably trip over Clark Kent. Does he have anything to say about the of the news business?

GHIGLIONE: For reporters, you know, the ability to see through buildings and see somebody is lying, that anticipates a lot of science fiction, which focus on the eye, a super-eye that can tell us much more than the human eye can tell us.

BROOKE: But, of course, Superman comes by his superness naturally. In the 1979 film Death Watch, starring Harry Dean Stanton and Harvey Keitel, journalists are modified.

GHIGLIONE: Yes, Roddy the reporter, played by Harvey Keitel, has a miniature camera implanted in his head so that he can watch human death occur. And, at that point, death is no longer occurring, so this is a major news event.

[CLIP]:

HARVEY KEITEL AS RODDY: Whatever I see, mysterious, terrifying, I just watch it, and it’s on film, forever.

[END CLIP]

GHIGLIONE: And then there’s another similar kind of story where Maya Andreyeva, the News One telepresence camera in Raphael Carter’s The Fortunate Fall -

BROOKE: In 1996.

GHIGLIONE: Right, she can transmit to viewers the holographic memory of interviews. And so, the event is vivid and complete, as if it’s happening right there.

BROOKE: But before implanted cameras and transplanted memories, there was the indelible Max Headroom, a computerized reporter in the days before computer technology was good enough to actually depict a computer reporter. So he was covered in foam and latex and he wore a fiberglass suit.

[CLIP]:

MATT FREWER AS MAX HEADROOM: M - M – Max Headroom here. [LAUGHING] Actually, I'm not here, because I live 20 minutes into the future. You want to join me here?

[STATIC NOISE]

[END CLIP]

BROOKE: Let's talk about another image that science fiction writers came up with, with regard to news, and that is journalist-free dystopias -

GHIGLIONE: Yes.

BROOKE: - like, like those described by novelist William Gibson, who created the cyberpunk genre, starting with Neuromancer in 1984. That is a world where all your information comes by and through essentially hackers.

GHIGLIONE: Yes, and I think there are many people who would say today, we are all journalists, so there’s not a special class of professional that’s necessary anymore. I don't believe it. The society depends on aggressive reporting. The world is extremely complicated and so to get at the truth, or a version of the truth, requires real work.

BROOKE: Is there any prediction that struck you as more likely than another?

GHIGLIONE: Oh, I don't know what’s more likely, but I am intrigued about moving beyond the handheld devices. I remember hearing somebody who’d invented the handheld device talking about implanting various devices in the human body that might take care of delivery of news and everything else. So who knows where all of this is headed?

BROOKE: As you quote Einstein, “If at first an idea does not sound absurd, then there’s no hope for it.”

GHIGLIONE: Yes, I love that. The future is likely to be counterfactual and not built on what has just happened.

BROOKE: Thank you very much.

GHIGLIONE: Thank you.

BROOKE: Loren Ghiglione teaches at the Medill School of Journalism.