Detainees Detail Troubling Conditions within New York City Jails

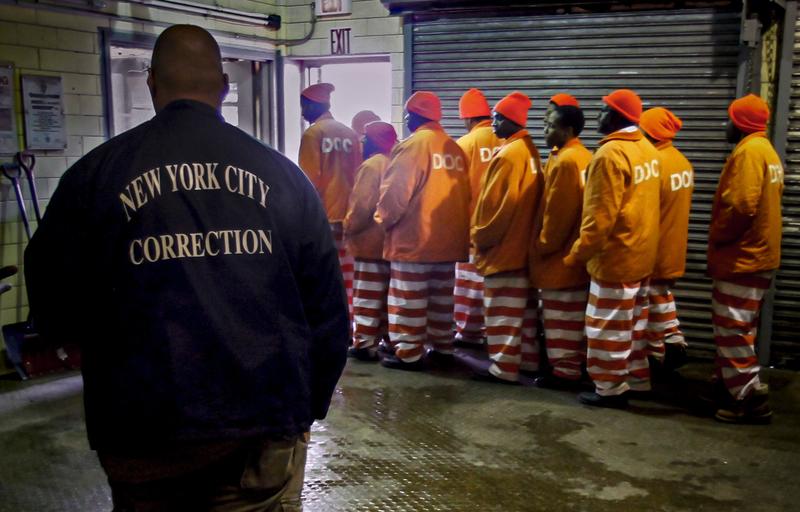

( Bebeto Matthews / AP Photo )

[music]

William Sanford: There's been people with no mattresses, just cuffed in the cells, and it'd be one officer ignoring them. There was maggots all over the garbage cans, there's big waterbugs, roaches, and everything. They really just leave you in there. It's like they pay you no mind.

Melissa Harris-Perry: That was William Sanford, a 35-year-old man currently detained in New York City's Rikers Island jail facility. He spoke last week with WNYC reporter Jake Offenhartz. Now, recent visitors to Rikers have described similarly disturbing conditions. I just want you to remember most people in Rikers have not been convicted of a crime. They are living in these conditions while awaiting trial. New York Governor, Kathy Hochul has sought to reduce the Rikers population with her recent signing of the Less is More Act, ending the policy of sending people to jail for parole violations, including marijuana use and missed curfews.

Kathy Hochul: The Board of Parole under my direction will have 191 people released today. They have served their sentences under the dictates of the new Less is More, but they shouldn't have to wait for the enactment date.

Melissa Harris-Perry: The nearly 200 people that the governor mentioned there had all been detained at Rikers Island. Last week, New York City Mayor, Bill de Blasio toured Rikers, a visit he had reportedly been putting off for weeks. In a combative press conference, the mayor declined to give specifics on the conditions he witnessed, instead repeatedly focusing on his administration's plans to close Rikers by 2027.

Bill de Blasio: I'm going to tell you what I've done under my watch. I've put the plan in place to get us the hell out of here. That's the bottom line. It's a place that is structurally broken, but within that, we can make a lot of improvements in the short term. The real answer is to get off Rikers Island once and for all.

Melissa Harris-Perry: The mayor also said that recent changes to policies on Rikers are already having a "real impact" but according to Alfred, another man detained at Rikers, who spoke with

WNYC last week, that simply hasn't been the case.

Alfred: Nothing changed. They had the people, the Mayor come through here, they hid the people at intake. There was two intakes, a [unintelligible 00:02:29] intake and a regular intake. They hide people in the gym, you know what I'm saying? When people come there like the Mayor, the Governor, or whatever. Whoever comes here to see what's going on, there's nobody in intake. You know what I'm saying? Usually, it'd be 30 people in one cell and every cell packed. When I came through intake, it was 30 people in one cell. I got here on a Saturday and I ain't get to the house that I went to until Tuesday.

Melissa Harris-Perry: The problems extend beyond Rikers. 12 people detained in New York City's jails have died this year, and at least 5 of those deaths have been suicide. Recent COVID outbreaks have led to delays in court hearings for a growing number of detainees. As of last week, 5,600 people were being held in New York City's jails. The vast majority of them have not yet been on trial. I'm Melissa Harris-Perry and today on The Takeaway, we're going to examine exactly what is going on in Rikers Island, one of the world's largest jails.

For more, I'm joined now by George Joseph, law enforcement reporter for WNYC. Thanks for coming back on the show, George.

George Joseph: Hi, Melissa.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Now, you've been reporting extensively on the self-harm that's been happening in New York City's jails during the pandemic. What are some of the reasons that detainees are hurting themselves?

George Joseph: I think it's been a really hard time for people who are incarcerated in jails across the country during this pandemic. The reason I say that is because at the height of the pandemic, which as you remember, hit New York City here really hard first, a lot of services were suddenly shut down. All of a sudden, people can no longer go outside to get recreation time, they can't have visits from families, they can't access commissary to get really basic supplies like extra food. All these extra services that people rely on to get through in jails are suddenly cut off.

What was unique in New York, especially compared to other cities across the country, is that throughout the year, we also saw a big staffing crisis. Meaning hundreds to thousands of corrections officers were calling out sick, or even just going AWOL, not showing up to work. In recent months, it's built up to a crisis where the Department of Corrections cannot get detainees basic services. Getting them to housing units, cleaning up facilities, getting people food on time. This is coming to a boiling point where people are so desperate and in some cases they are taking their lives.

Melissa Harris-Perry: The conditions you describe, it recalls for me that at least early on, I think most of us have moved to the language of quarantine, but there was this language of lockdown. We're all on lockdown. This is a reminder that while many of us may have been living under a stay-at-home order, being on actual lockdown is a different set of conditions.

George Joseph: One of the things that gets people through jail time the most is family visits. That being cut off is really hard on people, especially as you mentioned at the top of the show, a lot of these people aren't necessarily used to being in jail. They're there pre-trial, they're awaiting charges, they are still having a hope in their mind that they may get out or they may beat their charges, or they may be proven innocent.

They are in this moment where not only do they not have access to family or services because of the pandemic, everything is being delayed. Court dates are being put off for weeks, and months. They have no idea when they're actually even going to get their day in court because of the shutdown. That's another psychological element where people are waiting and waiting and waiting, and feeling like I'm being tortured here but I don't even get to argue my case.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Given that there have been at least five deaths by suicide, and given what you're saying about the lack of even basic services like trash removal, and daily food on time. Are there protocols in place to prevent suicides in New York jails?

George Joseph: There are protocols, there are training of some corrections officers, and the Department of Correction has tried to assure the public that it is doing everything possible to train people in suicide prevention work. Not that guards hadn't gotten any training before, but they continue to train them. However, medical professionals that we've spoken to in the jails argued you can't really rely on those very specific trainings to stop this overall problem. By the time someone has gotten to such a point of desperation that they want to take their life, and there are many people in the jails like that. It can almost be in some cases too late because you're not going to catch and stop everyone.

On top of that, you have some of these guards who are working double, triple shifts by themselves in some of these housing units. There's a question of if they're capable of every time stopping these kinds of incidents from happening. Both one, capable physically and two, able mentally? Are they willing to go do those thorough checks? Do they care enough to stop things as they're happening? Those are concerns and fears that a federal monitor that is currently regulating and overseeing Rikers Island has raised in recent weeks.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Can you say more about that federal monitor? How did they get there and what is it they're meant to be doing?

George Joseph: New York City jail system has been a mess for a long time. In recent years, a federal judge appointed a person to regulate and oversee the jails. Every couple of months, they put out a new report recommending changes and showing progress on how the Department of Corrections has been doing in terms of violence and other indicators.

A few years ago, not that jail is a good place ever, but conditions were getting somewhat better, the population was going down. It looked like the city was on this path as Mayor de Blasio has envisioned, closing Rikers Island down and opening new community-based jails that are supposed to be better than the Island right now.

However, in the last year and a half since the pandemic started, the population has dramatically increased, putting those plans potentially in doubt, because the Close Rikers Plan relied on having a low population and we're not seeing that right now. It's not the highest it's ever been historically, but it's much higher than the plan requires.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Let's talk about that population growth for a moment. Certainly, part of it is about the pandemic and therefore the slowing of the judicial process due to COVID infections as you pointed out of both those who are being held as well as members of the court, that's obviously created a backlog. There's this other piece around the repeal of a certain bail reform. I'm wondering if you can talk us through a little bit how that has also contributed to the growth of the population at Rikers.

George Joseph: Like you mentioned earlier, the vast majority, almost 80% of people in Rikers Island and New York City jails are being held before a trial. They haven't been convicted of anything. They're there for a charge that they're waiting to have adjudicated. There are decisions that are made in court before they get to jail about whether they're going to stay in jail and a lot of this has to do with what's known as bail. When you first get to court, based on your charges, in New York, judges are supposed to determine whether you are a flight risk, meaning, are you going to skip out on court. If you are not a flight risk, they're supposed to release you.

In some cases, if you are a flight risk, they're supposed to release you with supervisory conditions, or in some cases with bail. That was part of a reform that New York State passed a few years ago to try to ensure that people are being detained more because of their flight risk rather than because of how much money they had. We've seen since mid to late 2020, judges are increasingly setting bails that people can't afford more often, and that has resulted in an increase in detention. A recent study found that about 700 fewer people would be in New York City jails if judges just reverted to their behavior from early 2020.

The same study found that about 1,000 people fewer would be in the city jails if judges followed the city's release recommendation. Which says that when someone is statistically likely based on an algorithm to return to court, which is the point of bail, theoretically, you should simply release them. What judges are doing, as we've reported right now is assessing, "Well, I think this person is a potential danger to community, if they pose any risk at all, I'm going to set a bail." Because so many of our people who were in the criminal justice system are so poor, they can't afford these bales and they end up going to places like Rikers Island where they experienced violence and in some cases take their lives.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Let's pop back for a second and talk about the Mayor's visit. Clearly we played a bit from the Mayor's press conference and he wasn't really clear about what he saw. Do you have any insight on what conditions the Mayor actually observed himself?

George Joseph: Well, we don't exactly know what the Mayor saw because his visit was something the city was obviously aware of, they could prepare for it. They allegedly had freshly painted the walls of that facility he visited, it appears that he's got some staged tour. What we can say from having spoken to many detainees and people working in the jails right now, is that over the last few weeks, the conditions have been just simply completely unsanitary. Excrement, urine all over the floors, people are screaming all the time. People are begging staff to give them some small morsel of food. It's just not meeting any basic humanitarian conditions.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Isn't that constitutional violation? I mean, we actually have documents that require at the core of who we are as a nation not to hold particularly American citizens, but really anyone in those conditions.

George Joseph: Well, I'm not an attorney, but I would bet money that there are going to be many civil rights lawsuits that are filed from this period that will be successful.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Have media had access? We know that there is this potentially staged, freshly painted tour for the Mayor, but part of the way that we managed to ensure that our elected leaders and our institutions are doing what the law says is we shine the bright light of media on them. Do reporters have access into Rikers? Acknowledging that it's the COVID period.

George Joseph: We have not gotten a tour of Rikers and in the way like the Mayor and some elected officials have gotten to see, wander the halls, talk to detainees, talk to staff, hear for ourselves, how it's been. However, reporters like myself covering this issue have spoken to people who are recently incarcerated, staff members who work currently there. There was a press conference that was held at Rikers Island in which the Department of Correction Commissioner here in New York basically begged staff to come back to work to try to help the jails run better.

To some extent, yes, but, of course, jails are a much more isolated institution than other institutions in society. That's especially the case in New York where our biggest jail complex Rikers Island is on an island separate from the rest of the city. There's a bridge to go in and there's a bridge to go out. You can only visit on certain days, you need to have permissions to get in, you have to give your press credentials beforehand and you can't just proactively call someone, you have to wait for them to call you. These information flow is not ideal certainly.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Talk to me about policy reforms, what is possible? Maybe what other states, not that jail is a happy and highly functioning place really in any of the 50 American states. Are there other states where advocates are moving so that conditions don't look like this?

George Joseph: How to fix or address the solution is a very political question right now. In New York City, we have two sides, where one coalition of advocates who represent corrections officers are pushing for more hires. They want to improve the ratio of staff to incarcerated people, arguing that that way, their members won't have to work double and triple shifts, and these overstressed and overstretched and unable to meet basic needs. However, that federal monitor who I referenced earlier who's overseeing the city jails, he has found that New York actually has a higher ratio of staff to detainees than most other comparable jail systems across the country.

His argument is, "Look, DoC is not using the staff they have properly. Not putting enough of them in detainee facing roles to where they're actually using their staff efficiently to get people their basic services." He doesn't think the problem is one of staffing, he thinks it's one of management and resource allocation. Then on the other hand, on the other side, you have the criminal justice reform advocates who inspired by the Black Lives Matter, Defund Movement, in some ways, are arguing that you need to reduce the jail population.

That that is a better way to improve the staff ratio by sending fewer people to jail in the first place so that with the few people that you have there, you can ensure that they get treated with dignity and get basic resources. Right now the Mayor has leaned more to the former solution. He's promised to hire some more guards, a new class of recruits is coming in. The city is attempting to recruit older guards who can come in from retirement on a faster basis, but it's not the amount that the corrections officers union has called for.

At the same time, as we've mentioned at the top of the show, Governor Hochul has moved in some slight ways towards decarceration, releasing about 200 people from city jails and moving some others to state facilities. It's not the major chunk that would ultimately change that ratio.

Melissa Harris-Perry: As you talk about the politics involved, obviously, New York City has an election happening next month. Is it possible that the results of that election can affect the future of the city's jails?

George Joseph: That really remains to be seen. The person who is expected to become the next mayor of New York City, Eric Adams, a Democrat, has promised to continue with the Mayor de Blasio, our current mayor's vision of closing Rikers rather. However, that would be contingent on getting the jail population down to pre-pandemic levels and even a bit lower. How he's going to do that is unclear because he hasn't articulated a vision for doing so. Similarly, he has expressed some concerns about what the Mayor's plans are to close Rikers and replace it with borough based jails. Things are really up in the air right now and this is a major question mark in New York City Mayor, Bill de Blasio's legacy. Because he has long rested on the achievement of having closed Rikers in the future and now that future is uncertain.

Melissa Harris-Perry: You and the On the Media Producer, Micah Loewinger, recently broke some news after reviewing documents that indicated that there are current and former New York City law enforcement officers with ties to the Oath Keepers, which is a Far Right extremist group. Can you just say a bit about that reporting?

George Joseph: Sure, last week, a hacker breached into the servers of this extremist antigovernment group, the Oath Keepers, which had some of its members linked to the Capitol riots or insurrection on January 6th. When that hacker got those documents and records, he or she, we're not sure who the person is, gave them to a internet transparency collective, which publishes hacked records like this. They posted the documents online and my co-reporter and I, Micah Loewinger started going through, combing through the records. Particularly we were interested in are there current or former members of law enforcement and the military that are shown to be members of the Oath Keepers. Because this group has long prided itself on having that tactical military like prowess.

For those who remember seeing some of the people who were accused of storming the Capitol as part of the oath keepers, they were wearing a cammo military looking stuff, along side having the Oath Keeper symbol. When we went through these records and there are hundreds of them for people in New York, and thousands of them for people across the country. We did find that there were several active and former law enforcement personnel in them, at least the same names.

Unfortunately, when we called those people, they declined to confirm their status as active members of the Oath Keepers right now, but we did find matching names. Not only to police officers who were on the force today in New York City and across the state, but also corrections officers, jail guards, current and former in some cases. Quite a spectrum here in New York state.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Do you see a main takeaway from that reporting, it's pretty jaw dropping?

George Joseph: I would say the takeaway is that, this issue of Far Right infiltration has been on people's minds for quite a while. What our elected officials are willing to do about this, how much they're willing to confront this issue is still unclear. When we presented our findings, the Mayor's office promised an immediate investigation, but also said later at a press conference, Mayor de Blasio said that a full department wide audit of the NYPD was not necessary.

He likened such a search for extremist ties to a McCarthy witch hunt, and to the gubernatorial level it's unclear to us what the governor is willing to do on that side of things. Whether she will do a more broad, comprehensive search beyond our initial findings is unclear. Because you've got to think that there are some people who didn't have their names in membership logs, but have these sorts of affiliations, perhaps more covertly. Are we as a government actually addressing this? That's one of the questions I have from this.

Melissa Harris-Perry: George Joseph law enforcement reporter for WNYC. Thank you for all of your reporting.

George Joseph: Thanks for having me. This was fun.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.