BROOKE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. On this episode we’ll be strolling down one of our Memory Lanes; a bi-way lined with bones and running with blood (is my prose too purple for this season of red and green?) Then I’ll just say that we’re devoting this week to True Crime. It’s all the rage…

CLIP FROM SERIAL- YOU’RE RECEIVING THIS CALL FROM ...PENITENTIARY…

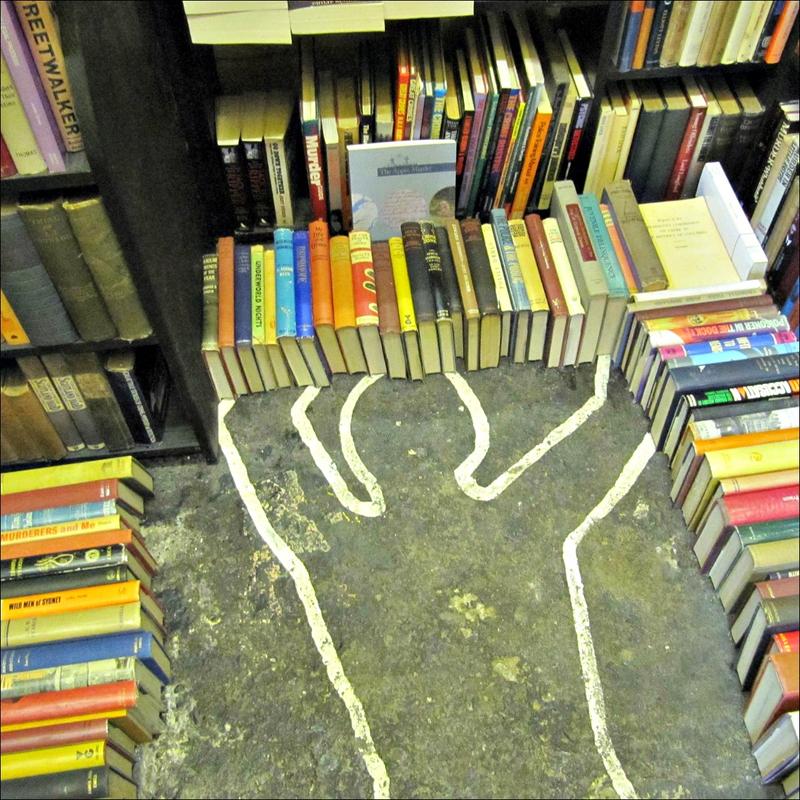

No, we won’t be talking about Serial. I mean, what else is left to say? Its the podcast that, more than any other, introduced the nation to the idea of podcasts. A gripping, thoughtful offshoot of This American Life, Serial spent 12 half hours exploring one 15-year old murder, and it ended 2 weeks ago, leaving the nation stoked for more true crime on the radio. Until Serial, radio was maybe the last narrative platform not conquered by true crime. Certainly it had long dominated TV, and movies, and been a best-selling book genre. In fact, when we picture true crime, that’s what we see.

BOB: ...You know, the glossy paperbacks full of crime, punishment, and ordinary people behaving badly that decorate the supermarket checkout aisle. But don’t let those foil covers fool you, says Salon senior writer Laura Miller: much True Crime rises above mere pulp. And she should know - she’s been a true crime aficionado since childhood. Helter Skelter, the book about the Manson Killings, was Miller’s first entrée into the genre.

LAURA MILLER: I first probably read Helter Skelter when I was babysitting, which is a very important vector of introduction to true crime for young women, is when you're babysitting and you look for the dirty books –

[BOB LAUGHS]

- and the sugary snacks. But probably the one that really just electrified me the most was on television. It was a docudrama with Robert Stack about the Black Dahlia killer. At the very end, he looks out at the audience from the television screen and he says, “You're out there, I know you're still out there,” to the killer. And it just — oh, the hair stood up on the back of my neck, and that was when I was really hooked. It was the way that this outrageous thing that they were showing on the screen - but they wouldn't show you all of it because it was too gruesome - was connected to the real world that I inhabited, you know, like maybe the Black Dahlia killer was not just out there but right outside my window.

BOB GARFIELD: And yet, there’s kind of a stigma attached to true crime, and I guess it's not hard to figure out why, but why don’t you tell me why.

LAURA MILLER: Most true crime really is pretty trashy. I mean, it's voyeuristic, it's lurid. You know, that’s been an earned reputation. It's just that not all of the genre has those characteristics, and there are things that the genre can do that really no other genre can. And, given how much of a factor crime is in all of the entertainment that we consume — Law and Order or detective fiction, which is pretty much the most popular form of genre fiction there is — you’re just consuming a huge number of narratives that are not necessarily representative of what crime and justice and detection are like in real life.

BOB GARFIELD: I have read Helter Skelter about the Manson killings. I read The Onion Fieldand I read Fatal Vision. None of those are prominent on my –

[MILLER LAUGHS]

- in my bookcases, at this point. And yet, In Cold Blood –

LAURA MILLER: Yeah.

BOB GARFIELD: - sits there right prominently.

LAURA MILLER: Capote is a great stylist, so it’s a high-class piece of work. Also, there's not a whole lot of mystery about the killing of the Clutter family, which was what Capote was writing about. But there is a mystery about why it came to be committed because the people who committed it, they were monstrous without being entirely monsters. It's a book full of unanswered questions. I mean, that to me is what defines a great true crime book, is its willingness to accept to be unanswerable about humanity and the impossibility of achieving justice.

BOB GARFIELD: If there’s a definition of serious journalism, it’s that the story matters. It has some significance to the reader, beyond the lurid particulars. Is that the litmus test for differentiating good true crime from pulp?

LAURA MILLER: I think that the right writer can make a particular crime matter, when the wrong writer cannot. And a great example is Robert Kolker's recent book, Lost Girls, which is about some bodies of young women had been found on Long Island, and no one is really sure if it's a serial killer situation. It's pretty ambiguous. Most of his book is the story of these young women and their lives and how they came to be in the situation where they were killed.

Now, there is a New York Post way of telling that story, which is that they were all call girls who were working off of mostly Craigslist and there's this scary monster, bogeyman-like figure out there. Or there's the question of how someone becomes a victim, told in a way that brings in the whole social context, so that it becomes something more than just a freakish scary occurrence that you kind of goggle at. And it, instead, looks at it as an inevitable symptom of some aspect of our society. The stories, together, move our frame of mind to a fuller grasp of reality.

BOB GARFIELD: In addition to your other duties for Salon, you write a book column every week.

LAURA MILLER: Right.

BOB GARFIELD: You believe that we are in a “golden age” of true crime. How so?

LAURA MILLER: Well, some of the great books that have come out just in the past couple of years have been Raymond Bonner's Anatomy of Injustice, which is the story of a wrongful murder conviction. There is a book that’s just published by a group of people at the Columbia Law School, called The Wrong Carlos, which is about another wrongful conviction that resulted in an execution in Texas. There's Errol Morris’, A Wilderness of Error, which is a reconsideration of the Jeffrey MacDonald conviction for the murder of his family.

BOB GARFIELD: Possibly one of the most written about true crimes –

LAURA MILLER: Yeah.

BOB GARFIELD: - outside of the Kennedy assassination.

LAURA MILLER: It’s – it was written about by Joe McGinniss and then Joe McGinniss was written about by Janet Malcolm, and now the whole kit and caboodle has been written about by Errol Morris.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, we’ve discussed some classics.

LAURA MILLER: Yeah.

BOB GARFIELD: What is the ultimate desert island classic in this genre?

LAURA MILLER: Oh, God, what a question! You’re supposed to say In Cold Blood, which is a really magnificent piece of work. But I think I would pick A Wilderness of Error. What it really brought home to me is the way that we think that we can look at the evidence and get a definite answer, but the more you look at it, the more you see. And, the more you know, the less certain you become. And that, to me, is really the best message that the best true crime delivers.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Laura, thank you very much.

LAURA MILLER: Thank you for having me.

BOB GARFIELD: Laura Miller is a senior writer for Salon. Her piece on the subject is titled, “Sleazy, bloody and surprisingly smart: In defense of true crime.”