BOB GARFIELD: Harvard Professor Peter Galison has calculated that since the late 1970s, the US may have produced a trillion pages of classified info, more than 200 times the entire Library of Congress. According to government figures, an estimated 1.4 billion pages of government documents have been declassified since 1980. These pages are out there, in various stages of redaction and variously dispersed, in archives, law offices, in the basements of journalists. What there is not is a database of all declassified documents available to researchers.

Enter then, The Declassification Engine, a project of Columbia University faculty and graduate students to amass a central database and use data mining techniques to understand the mechanics and mentality of secrecy, and perhaps to unlock some secrets along the way. Historian Matthew Connelly, who is leading the team with statisticians and computer scientists, says it's all about identifying patterns in what gets left out.

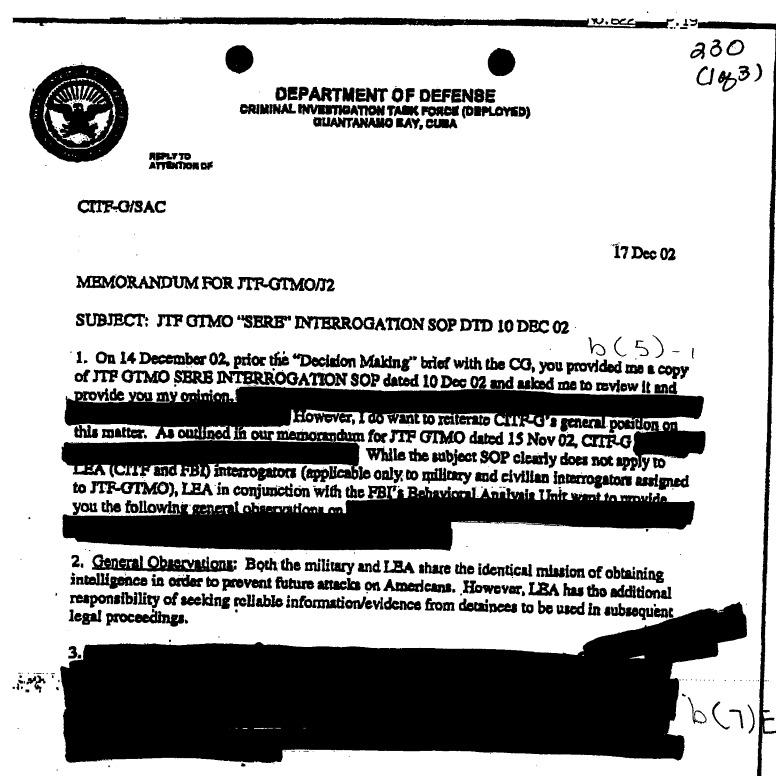

MATTHEW CONNELLY: In some cases, over decades, people will keep asking for the same document. They’ll keep asking for that UFO schematic from Area 51. And if you collect enough of these – and we have thousands of them now – you can begin to make out the broad patterns in the kinds of things that are kept secret.

BOB GARFIELD: Where do you get them?

MATTHEW CONNELLY: We went to the National Archives and we asked them nicely if they would give us 1.4 million State Department cables, and they did.

[BOB LAUGHS]

[LAUGHS] We also had the help of a big and great research library, Columbia University. You know, I should also mention, we, we've gotten a lot of support from the Journalism School at Columbia, the Brown Institute for Media Innovation. We've also gotten some commercial vendors who sell databases to libraries to let us look at their data. And what we’ve begun to do is to put together what I think will soon be the largest collection of declassified documents in private hands in the world, where people can explore this history and have a whole set of web applications to begin to analyze them.

You can run a statistical analysis to find the kinds of words that are typically redacted. You can also look for names. You can even create a kind of word cloud and see which names jump out at you. And the biggest name of all is Mohammad Mosaddegh. He was the Prime Minister of Iran in 1953, and he was overthrown by a coup that was instigated by the Central Intelligence Agency. Even now, and for decades, officials would deny any knowledge of the coup that overthrew Mosaddegh. And this is something that you find systematically through the whole process of redaction. It’s particularly covert operations that tend to be concealed, even when those operations become common knowledge.

BOB GARFIELD: Operation Boulder, tell me about that.

MATTHEW CONNELLY: There is a program that started just after the Munich Olympics, when the US began to worry about international terrorism, whereby anyone who had an Arabic-sounding last name and applied for a visa to come to the United States was gonna get investigated by the FBI. Now, the reason why we know about this is precisely because government officials were withholding those cables from researchers, about 30 years later, which was - that is just after 9/11.

And so, precisely at the moment when we really needed to know more about that history of how it is we’ve tried to - you know, in the name of national security, you end of profiling ethnic communities, that history, which would have been most valuable to us, was exactly the history they didn't want us to know about. So that's what you can do with this kind of data mining that we should be grappling with, as well.

BOB GARFIELD: What else gets redacted that defies the logic of secrecy?

MATTHEW CONNELLY: Well, I tell you, one of the real concerns that motivates us is whether officials are actually following policy, whether they’re following the law in the kinds of things that they redact. So one of the things that we can begin to do is we can cluster these different redactions, according to the specific clauses and executive orders that officials are invoking. Now, there are examples, you know, many of them, about how it is that officials will sometimes withhold information, simply because it's embarrassing. So what we can begin to do is to look, with real data now, as to whether officials are actually following policy and following the law in the things they choose to withhold from us.

And so, what we're trying to do is to correct the inherent bias in the public record. And if we can begin to do that, again, just to make out the broad patterns of the kinds of things that are typically kept secret, we can begin to infer what it is that we’re not seeing behind that redacted text.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, you went to the CIA, which already has a database of declassified documents, and they told you, hey, listen, you can look at them one at a time, you know, in some hangar somewhere in Maryland, but we’re not giving you access to the database. Why do you suppose they refused that request?

MATTHEW CONNELLY: Well, the CIA has anticipated for many years now that researchers are gonna begin to use computational methods to try to put together the pieces. It’s called the Mosaic Theory. And the idea is that even if you are only looking at what seems like an uninteresting banal information, if you can find enough of it and you can start to put it together then you’re gonna make out a bigger picture; you’re gonna see the mosaic the CIA would rather you didn't see. So for many years now, the Central Intelligence Agency, the NSA, etc., they have withheld a lot of documents, a lot of information that really, on the face of it, doesn't pose any security risk to anyone. And they’ve been doing it in anticipation, you know, of people doing this kind of data mining research.

BOB GARFIELD: Inasmuch as the declassification engine, by employing the Mosaic Theory, is already something of a decryption engine, won't its existence make the government more, not less, heavy-handed with classification and redaction?

MATTHEW CONNELLY: When people hear about supercomputers and they hear about machine learning, and so on, they have visions, I think, of, of how it is that we could blow every government secret. Well, we can't. And, even if we could, we wouldn't. Nobody on this project thinks that there isn’t a role for official secrecy. And, in fact, the, the current system is one that is so complicated that it’s actually doing a poor job keeping the secrets that really have to be protected.

So, Bob, you know, the irony here is that government officials themselves realize that official secrecy is growing out of control. There’s been a whole series of panels and commissions that have called for the very thing that we’re trying to do, that is to develop new technology that can automatically review documents to identify sensitive information or, at the least, prioritize those millions of documents to figure out which ones require closer scrutiny. So, in fact, this technology is something that can be useful, important for the citizen, for the scholar, for the journalist, but it's also something that government officials themselves are asking for, because they can't do their job without it.

BOB GARFIELD: Matt, many thanks.

MATTHEW CONNELLY: Thank you so much, Bob.

BOB GARFIELD: Matthew Connelly is a historian at Columbia University.