David Byrne on Musical Democracy

[music]

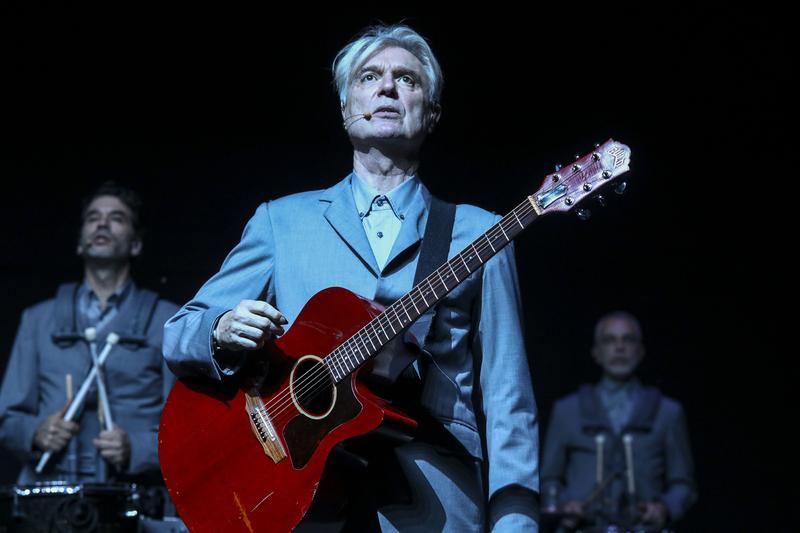

Kai: Hey, everybody. This is Kai. We have a podcast special for you this week. You might recognize this song. It's Slippery People by The Talking Heads performed here by their front man, David Byrne. It's a song that evokes thoughts about faith. Not just about religion. That's in there too but I mean, faith like faith we put in people, in each other about how we all try to navigate the challenges of our lives together. That might be why this song is a good fit for Byrne's show, American Utopia.

It's a live Broadway show in which he performs his music almost as a catalyst to a wider conversation about living in a plural society, you, me, us, and what's possible if we can make that work. I was lucky enough to talk to David Byrne about all of this recently, about his music, about the show, and about the musical democracy that is on his mind. Check it out. I hope you'll enjoy it. Here you go.

David, thank you so much for this time.

David: Thank you. Thank you for arranging this.

Kai: I want to start with you spoke with a friend of mine actually, Rich Benjamin for The New Yorker recently and you said something to him that really stuck with me. You were talking about the love that you feel coming from the audience while performing American Utopia. You said though that you try not to take it personally because you know it's not really about you. You also nonetheless try to reciprocate it in the moment.

I have to say, that almost made me cry because while it's really beautiful to me, it also sounds like a lonely thing to experience. I bring that up because it just reminds me how I felt watching the show in general and your work in general of having these overlapping often conflicting emotions. I don't know. I just wanted to start with asking you to say more about that feeling you described around love.

David: Okay. It’s like a lot of whether it's actors or musicians, performers in general, we as audience members, we confuse that person's work with the real person. It happens all the time. People think they know an actor because they've seen them in a lot of roles and they think that's what they're like and that they feel like they know them personally but you don't. That's their work. That's their job. I feel like a lot of the appreciation and love or whatever that's coming from the audience, I think is coming from the work and it's not about me, personally.

I have to try and not get a swelled head and big ego about all that and not think, “Oh, they love me. They love me. I'm so great. I'm so great.” To a large extent, it's the work that they love that is affecting them. I'm the delivery service for that. Okay, maybe I'm doing a pretty good job of it but I also feel like there is a little bit of a difference between the work and what that means to people and me as a person.

Kai: Well, American Utopia, in general, seems to me to be interested in, I don't know, in the contradictions and challenges and joys of being social creatures. That's a lot of what I take from it, craving connections as humans and the complications of that. Is that right?

David: Yes. A lot of it is the journey of this person embodied by me, and is based on loving my own experiences, from being socially awkward and gradually over decades, finding oneself in a little community where you feel comfortable. In my case, that might be a band. Then gradually becoming comfortable enough that you can engage with strangers and also become socially engaged, socially active in terms of issues and things like that. For me, anyway, I find that that's a step-by-step project. The show starts with me holding a brain.

[music]

It's like I'm living inside my head. Then by the end of the show, we're talking about the whole society.

Kai: Along those lines, when you introduce the song, Everybody's Coming To My House,

[music]

You say that in the show that when people cover it, it comes off as this happy celebration, but for you, it was all about anxiety that everybody's coming to my house. Tell me about that. It's interesting even that you notice the difference.

David: Yes. We invited a high school choir in Detroit to cover the song, to do an interpretation of it.

[music]

I don't know exactly what they did but the feeling I got from the song was very different from the feeling I got from my recording of it.

[music]

In my recording, you could sense that this is a guy who's a little bit apprehensive about having to deal with, socially with a whole bunch of people.

[music]

Whereas these kids, when they did it, they couldn't wait to have a bunch of people over. They were just welcoming everyone and inviting them to come over.

[music]

I thought that was wonderful and maybe I can learn something from this.

Kai: The show grew out of your 2018 album. Obviously, it was conceived before we all experienced a lot of the hard stuff that complicates our American Utopia as it were now, COVID, the near-collapse of democracy, the reaction to George Floyd's murder. But what were you seeing in our lives that did creep into this show as you were conceiving it back then because it's not a literal statement about utopian America.

David: No, it's not that and it's not to be taken that way that hear the saying that we live in a utopia or me giving prescriptive directions like, “Oh, well, this is what we need to do,” but yes. We touch on immigration, we touch on race, we touch on voting, we touch on a lot of subjects that have since then become the main focus of our lives in some ways but it was definitely in the air already. As with a lot of things, the pandemic just threw things into bigger relief but it was more the tour.

When I started thinking about how to perform this material and mixing some older material, I became very concerned with what I saw happening in the world, in the country that I live in. I thought I need to at least acknowledge that. I'm not going to provide everybody with a lot of answers but you have to acknowledge what's going on in the world that we live in and not only provide an entertainment. Although that's-- I have to do that too, otherwise, people are just going to walk out.

Kai: It is ultimately quite a joyful celebration. That's the experience of it. At least watching it, people literally dance in the aisles. I watched the HBO version, which was directed by Spike Lee so my boyfriend and I danced on the couch instead of in the aisles. But the film version really does still capture how much fun the audience appears to be having throughout the show. How important was that to the experience as a whole?

David: I thought it was very important that people experienced that utopia that we're talking about, just a little bit. They just get a little taste of it whether it's dancing or the joy that I see in the audience. As I said, a lot of what the show does is not prescriptive or descriptive. It's not me telling people, “This is what's going on, this is what I see and this is what we should do.” I want them to witness it. I want them to witness what's possible. That's to me, what a lot of the show is about. They see what we can be. Granted, it's just a show but it still is very affirmative that way.

Kai: Along those lines, I'm struck by the mobility of the performance. For anyone who hasn't seen the show, all the musicians, including the drummers are equipped to walk and move freely anywhere on the stage as they play. How did that format then shape what you were trying to achieve?

David: That was something I'd been building to for many years. I myself had gone wireless for a while. Then on a tour that I did with St. Vincent, we had a brass section and the brass section was completely mobile and wireless. I just thought, “Can we take this further? Can we have everybody, even the drummers, keyboard player, can we have everybody mobile?” When we did that, these other things happened.

One thing is that the stage- -becomes more democratic. The drummers can come to the front. They're not relegated to a platform in the back. They can be in the front and I'm in the back.

We're constantly in motion so that everybody's at the front at some point. That's a big thing. The other thing is that by eliminating all the stuff that's onstage, it really does become about the people, how they relate to one another and how they relate to the audience. It's not about special effects and video screens and all the other kinds of stuff that we often use in shows.

Kai: It's stripped down. Again, for people who haven't seen it, the set is also quite stripped out; gray suits, gray background, without shoes. All of that, I gather then is about this point of just it's us as humans together.

David: Yes. If we take everything away, all this left is us.

[music]

Kai: It's a large company of musicians, and it must be said that it seems like an intentionally kaleidoscopic company to me in terms of race and gender and background, but also styles and instruments and roles. It's kind of beautiful chaos on the stage. I have to assume that is also intentional.

David: Well, yes. Obviously, we want to show the diversity that exists in this country that isn't always represented on stage, but it's there. The talent is out there. Lots of musicians I work with-- well, I could protect the drummers. The drummers, in order to get all these different sounds like what we'd have on recordings, they've started bringing in Afro-Latin instruments and Brazilian instruments and all kinds of stuff. There's a real drum and percussion symphony going on back there to achieve all these sounds.

[music]

Kai: Now that having heard you talk about the democracy of the stage, it's also a democracy of sound. It feels like there's moments where it's almost cacophonous.

David: We tend to see it as being very organized, but yes.

[laughter]

There's a lot of grooves going on.

Kai: Toward the end of the show, you cover Janelle Monae's protests song, Hell You Talmbout?

[music]

How do you choose to include that?

David: We included that in the tour. Before we did the Broadway show, I felt as an artist, as human being, we have to reflect the world that we live in. Although we want to be entertaining, we want to also reflect what's happening around us.

[music]

I heard that song a little bit before that, and just thought it was very moving and beautiful in that it doesn't tell you what to do. It just tells you, “This happened, don't forget these people. These are all human beings whose lives have been taken.” Yes, I felt it was a beautiful way of putting that forward. She liked the idea that we were doing it and that meant a lot. Yes, so we just kept doing that when we moved to Broadway.

Kai: It's followed by One Fine Day, the song One Fine Day, which is just this gorgeous choral rendition.

[music]

Part of me, David wanted to reject that song, if I'm honest. Like it was too beautiful, with too hopeful of a response, but of course, I couldn't because it is so beautiful, and it is so hopeful. I just wonder how you reacted to my experience with that.

David: We had exactly the same experience. When we were on tour, we would do Hell You Talmbout as like an encore number and we couldn't follow it with anything. We felt like, "No, we can't follow this with anything else. We're going to leave people with this." Then for Broadway, we thought, “No, let's see. Let's experiment and see if we can leave people on a slightly more hopeful note.”

We present them with reality, but then offer them the idea that we can actually move on from this, we can be better than this. We tried a whole bunch of different endings. We did out-of-town tryouts in Boston. I think we had like three different endings for the show and that's the one we ended up with.

It does take away some of the punch that you've received, the punch in the gut you've received from Hell You, but it also gives you the sense that, "No, we can actually do something. This is not impossible. There is actually a possibility that we can actually move on from this."

Kai: We talk a lot on this show, editorially on our team about not leading people down dark alleys and leaving them there given that stuff that we cover so often and it sounds like a similar conversation.

David: That's a really good way of putting it, yes. You want to let people see the dark alley, but you don't probably want to leave him there.

Kai: At least the version that I saw you, the encore does become the classic talking head song, Road to Nowhere.

[music]

Maybe that's just a crowd-pleasing encore, but I'm guessing not from the way you think about your work. Why did you decide to end a show called American Utopia with a song called Road to Nowhere?

David: [laughs] Well, it is a crowd-pleaser. Despite the title and the lyrics, it's actually very uplifting. That's one of those songs that does that. What it says and how it makes you feel, is a contradiction.

[music]

Kai: This is what I said at the beginning. Honestly, for me, that's almost definitive of your music in general. Is that a fair take?

David: Yes, it happens. It happens occasionally. I love that about music. It can hold contradictions like that or it can hold different feelings and ideas at the same time, I’ve often felt that, in a lot of Latin music for example, the lyrics can be really sad, very melancholy and tragic, but the music, the music is giving you hope. It doesn't say anything in words, but it gives the singer and the listener hope. You have these two different things imbalanced, trying to achieve a balance between each other. I thought music can do that. You can't do that in too many forms.

Kai: How does the meeting feel now compared to when you first wrote it?

David: It has stayed as being uplifting despite what it says. If we took it literally, people would think, "Oh, he thinks we're in a hopeless situation, climate change, everything else, we're just going to hell in a hand basket and he's just saying, well, it's been a nice ride. Here we go. We're all going down with the ship here." I don't think that's what comes across, but as I said, that's what music can do.

[music]

Kai: David Byrne's American Utopia is running at Broadway's St. James Theater through early April. You can also stream a filmed version directed by Spike Lee on HBO Max. You can find us on Sunday evenings, 6:00 PM Eastern. Stream it at wnyc.org/radio. See you there.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.