Critical Race Theory: What It Actually Means

( ASSOCIATED PRESS / AP Images )

Announcer: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

Regina de Heer: Have you ever heard of Critical Race Theory or the debate about it?

Speaker 1: I haven't, unfortunately.

Regina de Heer: Have you heard about Derrick Bell?

Speaker 1: No, I haven't. Definitely, if I could write down his name, I'll Google him.

Speaker 2: I think critical thinking is very important.

Speaker 3: Critical thinking or Critical Race Theory?

Regina de Heer: Critical race theory.

Speaker 3: Oh, it's Critical Race Theory.

Regina de Heer: Critical race theory. Have you ever heard of that?

Speaker 4: No, what happened?

Regina de Heer: Have you heard of Critical Race Theory?

Speaker 5: Who?

Regina de Heer: Critical race theory. Have you ever heard of that?

Speaker 5: What is it?

Speaker 1: I don't know. I feel so silly because I know there was a point where I knew what it was. Isn't it just of examining your actions or kind of like what you see through like a race-conscious lens maybe?

Speaker 3: Yes. I'm not sure how I would define it. I feel like I know what it is but I really don't know how to like put it into words properly.

[pause 00:01:00]

Kai Wright: It's Notes From America. I'm Kai Wright. Welcome to the show. A special welcome to those joining us for the first time this week from KSJD in the Four Corners region of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. Glad to have you in the conversation. It's totally understandable if you cannot define Critical Race Theory. Honestly, if you've not been to law school or had some form of graduate education in the humanities, it's just really unlikely you would have even heard the phrase before it became the latest jumble of words loaded into the pull-string doll of right-wing media.

Another incantation to fear for those who feel threatened by a changing America. Phrases like, defund the police or Antifa are, for you old-timers out there, remember Benghazi, Benghazi, Benghazi, Benghazi. Or even death panels, remember that one from the early Obamacare debate? Anyway, the thing is that this one is particularly sad to me because Critical Race Theory is actually rooted in a really thought-provoking set of ideas, and it has a fascinating backstory.

We're going to learn that story this week. We're not going to take calls, but we are taking voicemails. You can always talk to us by going to notesfromamerica.org, look for the record button, and chime in. Just be sure to include at least your first name and where you're calling from. Our guide through the history of Critical Race Theory is New Yorker writer and Dean of the Columbia University School of Journalism, Jelani Cobb. He wrote about this history in an essay for the magazine a couple years ago.

Kai Wright: Hey, Jelani, thanks for coming on.

Jelani Cobb: Thank you.

Kai Wright: I learned a new phrase that I do love reading your piece. You talked to the legendary, to my mind, legendary legal scholar and nation columnist, Patricia Williams, who said, what's been done to Critical Race Theory is quote, definitional theft. I love that phrasing. Explain what she meant by it.

Jelani Cobb: She meant that they had taken a term that existed that had a definition and completely usurped it. Stolen effectively the name Critical Race Theory and applied it to a completely different set of ideas that have nothing to do with what the originators and the scholars who founded this field were really thinking about.

Kai Wright: You quote the right-wing activist Christopher Rufo, who pretty clearly spells out the plan of attack for that definitional theft on what he calls the brand of Critical Race Theory. Who is this guy and why is what he said important to understand before we even get into this conversation?

Jelani Cobb: He's really the person who's at the center of the uproar about Critical Race Theory is a right-wing political operative. He said literally that he wanted to take the brand and, quote, freeze it, as an association with a whole array of negative things in people's minds. This was done really as a counter-offensive after millions of people saw that video of George Floyd's death. Really would driven to literature, to research, to history to try to understand how this could come about, what society are we living in?

That really unsettled, I think people who were in the right-wing part of the political spectrum. This was an attempt to discredit Critical Race Theory, but really a more substantial attempt to discredit a whole body of anti-racist scholarship that people have turned to after George Floyd's death.

Kai Wright: I think it's so interesting that he even used the word brand. This is a set of ideas and he called it a brand.

Jelani Cobb: I think that's one of the more grotesque parts of modern life that everything is a brand. I'm old enough to remember when people were trying to establish a good reputation and people want to establish a brand. It's imported the language of marketing into our daily lives and in this case into our intellectual lives and into social policy and activism.

Critical Race Theory is not a brand [laughs] it's a movement with distinct intellectual roots with parameters and specific questions about the legacy of civil rights, discrimination, and anti-discrimination law, and the ways in which racial hierarchies have been able to reassert themselves despite the best intentions and successive waves of attempts to reform.

Kai Wright: Of course, the irony of all this is that both Critical Race Theory specifically and the man whose work it grew out of, this was all a critique of mid-century liberalism and really of the civil rights movement itself. I'll be honest, Jelani, I didn't fully appreciate that before reading your piece.

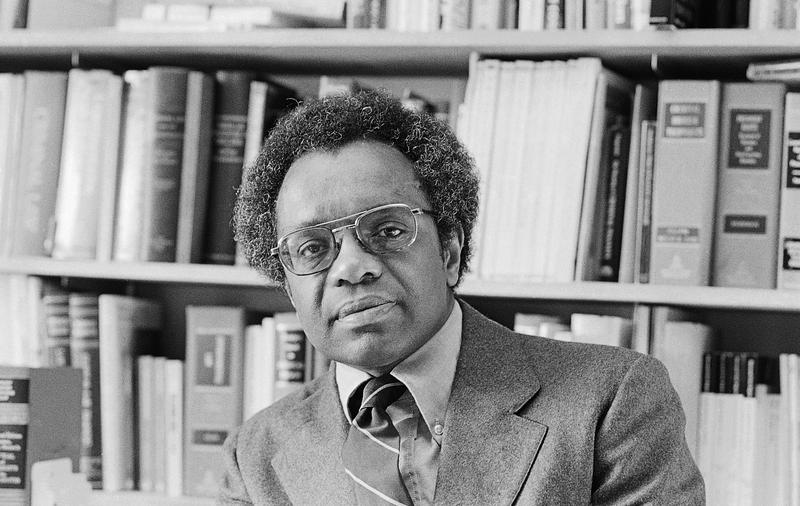

I actually suspect there are a lot of people on all sides of the political spectrum out here talking about this idea who don't actually know what it is and where it came from. That's why we wanted to sit down with you. You tell the life story of Derrick Bell. Introduce him in a few sentences for those who haven't spent their lives in the halls of academia. Who was Derrick Bell?

Jelani Cobb: It's really hard to introduce Derrick Bell in a few sentences, but I'll do my best. Derrick Bell was activist. For the first part of his life, he was a legal activist who risked his life to file and fight desegregation suits in Mississippi between 1960 and 1966 when he worked for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

The second part of his career was in academia as a law professor, when he began pioneering work that essentially critiqued what he had done as an activist lawyer. That sent him down the route of questioning the underpinnings of the legal and to a certain extent the social strategies of a civil rights movement and the ways in which liberalism had failed to uproot racism in American society.

Kai Wright: I think you did it well. Let's walk through and unpack all of that. His first job was out of law school at the Department of Justice. This is 1957, I believe. He's a registered member of the NAACP and the DOJ wants him to quit that group and instead, he resigns.

Jelani Cobb: Yes. Which becomes a theme in his life. Derrick Bell was the first Black attorney in the Civil Rights Division at the Department of Justice. Being hired there in 1957 was no small deal. This was a very prestigious and significant position that he had attained, but he was a member of the NAACP. When they told him that he would have to quit, he just decided that he would quit, but he wasn't going to quit what they thought. He wasn't going to quit the organization. He was going to quit the DOJ.

This came up again and again in his career, subsequently. He quit as the Dean of the University of Oregon Law School because they refused to extend a job offer to an Asian female candidate who was the third person on the list after two prior candidates, both white men, had declined the position.

Kai Wright: It suggests, and you talk to people who knew him who suggest this, that a certain personality.

Jelani Cobb: Certainly, right.

Kai Wright: Talk about that, it's more than just his ideology. It sounds like he was a person who was a bit of an absolutist, I guess.

Jelani Cobb: I think he was an absolutist about matters of principle. In the third instance where he quit yet another job and even possibly more prestigious in the DOJ was when he quit in 1990 Harvard Law School over its failure to hire and tenure a Black woman faculty member or any women of color. He said at the time, he gave a speech where he said that he could not afford to walk away from that job, but he also felt that he could not, in good conscience, tell his students to live out their principles if he failed to do the same, and you just find that as a theme in his life.

I also think that the one last thing I'll say is that one of the things that stands out to me about him and having learned more about him in the process of writing this was that he really was a person who was driven by integrity and driven by his sense of principle. He countenanced the beliefs and arguments with people who thought differently than he did and encouraged people to express themselves. He was by no means a zealot or an ideologue in any kind of way. He was trying to follow, I think, the most honest, intellectual path that he was capable of.

Kai Wright: Also, after he quits the Department of Justice in 1957, he lands a job at the NAACP instead. This is a really interesting moment in the history of civil rights, 1957. This is right after the end of the Montgomery bus boycott, and NAACP has litigated and won in the Supreme Court.

Jelani Cobb: That's right.

Kai Wright: He steps into that. In some ways, this is perhaps maybe the most idealistic time for the movement. Now, help situate us in time for the civil rights movement that he steps into, at that time.

Jelani Cobb: It's really a time of harvest, especially the legal part of the movement because beginning in the 1930s, when Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall were filing these cases across the country, and laying the groundwork for what happened in the 1950s it was lonely work, swimming against the tides, trying to get these desegregation suits past these judges. By the 1950s, they reach a point where all of a sudden, they have the wind at their back. It's a mixed metaphor here.

They are really moving. There's obviously Brown v. Board of Education, Montgomery bus boycott lawsuit, and then they began essentially an offensive across the South, filing thousands of desegregation suits, many of which were overseen by Derrick Bell. By the way, he's very much influenced by Thurgood Marshall. As a young lieutenant in the Air Force, he sees the Brown v. Board of Education decision and is immensely inspired by it. That's part of the reason that he goes to law school.

When you look at the moment that he arrived at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, that is one of the most exciting and fertile moments in that movement's history.

Kai Wright: Coming up the unexpected lessons that Derrick Bell takes from his time at the center of the civil rights movement, and how he arrives at a searing critique of liberalism. Stay with us.

Regina de Heer: Hi, my name is Regina, and I'm a producer with the show. You may remember that last year, we started the Notes From America summer playlist. We collected submissions from you and curated playlists that everyone could enjoy. While summer is here again, and I'm happy to announce we're launching our second summer playlist. A couple of weeks ago, I had a conversation with the guys from a band called Wake Island. They talked about how music has become such a powerful outlet for identity, filling a need as a search for their place in the Arab American diaspora.

Now it's your turn. What's a song that represents your personal diaspora story? Here's how to send us your response. Go to notesfromamerica.org and look for the record button to leave us a message. Start with your name and where you're recording from. Then tell us the name of that song, the artist, and a short story that goes along with it.

Feel free to include a little bit about your background as well. Make it your own and please make sure that your recording is at least a minute long. We'll gather all the songs and your stories and Spotify playlists that will drop regularly all summer long. I think that's everything. Thanks for coming to my TED Talk and I can't wait to hear from you.

Kai Wright: Welcome back, it's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright and this week, Jelani Cobb, who is Dean of the Columbia University School of Journalism, is telling us the true story of Critical Race Theory and of Derrick Bell, who is the man whose work inspired the set of ideas that have sadly been reduced to a political catchphrase.

Before the break, Jelani was explaining that Derrick Bell began litigating civil rights cases for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in 1957 on the heels of Brown v. Board of Education and just one of the most active promising moments in the legal movement. He was at the center of the action and he started having these experiences that made him not so sure whether what he was doing was actually helping. Jelani talks about a school desegregation case that came to belt from Mississippi.

Jelani Cobb: There is a Rosenwald school in the beginning, turn of the 20th century, a philanthropist by the name of Julius Rosenwald allotted money to build 5,000 schools for Black students across the South, tremendous act of philanthropic giving that transformed many communities. There was a Rosenwald school in a place called Harmony, Mississippi. The school's board, all-white school board, was opting to close the Rosenwald school there, the Harmony School.

That prompted a group of activists to form an NAACP Chapter and to start talking about what they could do to keep the school open. A woman who was the vice president of the chapter, a woman by the name of Winson Hudson, reached to Derrick Bell, and said, "We would like to keep the school open." Bell describe himself as being astounded because he said, "You do know that we are trying to desegregate schools so we can't fight a lawsuit to reopen a segregated Black school."

The fact of the matter is that the community was much less interested in desegregating the school than they were in keeping what they felt to be a quality Black school open in their community. This is the point at which there's a divergence that Derrick Bell comes back to time and again, in his work, a divergence in the interests of the NAACP, and the plaintiffs who they represent.

We ultimately do wind up representing these families in Harmony, Mississippi, and suing to have the schools they're integrated which happens. It gives you a sense of how people who appear to be operating on the same side are really sometimes operating at odds or have different interests.

Kai Wright: What did he do with that? You said he notices this divergence between somebody like Winson Hudson who's like, "No, what all I want, is quality education for Black kids. I don't care about the integration piece of it," and then NAACP wants the integration piece of it. That leads to this larger critique. What did he take from the divergence that he saw there?

Jelani Cobb: In order to understand how he evolves, we have to add in a little bit of history. There's lots that happens but we can just summarize it by saying, many of these school systems are integrated, at least in theory, which in turn sparks, a mass exodus of white students from the school systems into what they called segregation academies and effectively ensured that Black students would be going to overwhelmingly Black schools, even after so-called integration had taken place.

In turn, many of the public schools whose were never great in the South, never really wonderfully funded became even more poorly funded because there was less reason for white taxpayers to be invested in what happened in public schools. Derrick Bell looks at this play out in the 1960s and 1970s and he tells Winson Hudson, who he sees at a conference, who says, "I'm not sure I gave you the right legal advice."

She tells them, "I'm not sure you did either," which is fascinating moment. Because the fact of the matter is, a decade, two decades, after Brown versus Board of Education, you are still seeing Black students going to overwhelmingly Black schools. We also add an asterisk here or a footnote here to say that the problem was never that they were going to overwhelmingly Black schools.

The problem was that as long as Black students were segregated in one particular set of schools, it would be easier to underfund those schools, it'd be easier to sear up inequality. The ideal of integration was that if you put Black students and white students in the same schools, they would have to fund them because you would not want to deny a quality education to white students either, if it meant denying it to Black students.

This was one of the ideals that was at play but it ultimately plays out very differently. By the 1970s, Bell, he's really beginning what becomes a multi-decade effort at reassessing what happened in the course of the civil rights movement, and that reassessment is really the cornerstone of Critical Race Theory.

Kai Wright: That distinction was initially lost on Bell but it began to trouble his thoughts about the pioneering civil rights work he'd done. Jelani Cobb says that in the early 1970s, those misgivings became the foundational ideas of today's Critical Race Theory and they were in fact disturbing ideas.

Jelani Cobb: He also felt that if you were to institute as massive a set of changes as the civil rights movement brought about, and still wind up with outcomes that were reminiscent of what happened before the civil rights movement, then it meant that racism would not be easily uprooted from American society. It's around this point that he begins saying that we should consider racism to be a permanent feature of American life, which was enormously controversial when he first said it.

People believed, and one of the ethics of the civil rights movement had been that the society could change and that people could uproot racism. Here is a person who was a soldier on the front lines of the movement saying, "I don't think this is ever going to change. I think this is always going to be a permanent feature of American life."

This was just not really said. These were things you didn't really hear from the crowd that Derrick Bell was associated with. For a time, it created tensions, even in some of his personal relationships, as people wondered if he had just become jaded.

Kai Wright: To be honest, that is my perspective, that it's a permanent part of American society. I never really understood, and I've said it for many years, and I didn't understand that I was in a line of thought that started with Derrick Bell.

Jelani Cobb: Yes, I think a lot of people have that experience. A lot of people have that experience, that we have ideas that are attributable to what Derrick Bell was trying to figure out. We have had an easier route to drawing some of these conclusions precisely because he wasn't so invested in his own glory.

A lot of people would have just recounted their tales of great courage and achievement and never had the intellectual honesty to question whether or not this actually made the difference you were trying to make. Derrick Bell was one of the people who was willing to do that.

Kai Wright: At this point, we're in the mid-'70s or so that he starts to recognize this and it's a controversial idea at that time. There was another big Supreme Court case you point out around that time that shaped his thinking. That's in 1978 and it's the Supreme Court case that reaffirmed the purpose of affirmative action and college admissions but did so in a way that troubled Bell. How so?

Jelani Cobb: He's talking about the Bakke case, which is famous. It's the famous reverse racism argument. It is that a man by the name of Allan Bakke, who had applied to medical school, University of California system twice and had been rejected, but found that there were Black students who had lower scores who had been accepted, sued and said that he had been a victim of reverse discrimination.

The Supreme Court decision on it narrowly preserved affirmative action on the grounds of diversity and saying that it was permissible if you were diversifying the population, et cetera. That's been one of the main buzzwords ever since. Derrick Bell was incensed and deeply troubled by this. It really distills a lot of what his uneasiness had been, that in essence, the court was responding to specific racially intended policy and legislation that had excluded Black people from institutions of higher learning but they can only respond to it with the tool of color blindness.

He does not think that what happened to Allan Bakke in the admissions process is the equivalent of what happened to Black people who were turned away from universities irrespective of what their scores were. He said that as long as we are making these two things equivalent, as long as we engage in this false equivalency, we'll never actually be able to achieve racial progress. That's why I think Bakke really is at the cornerstone of his evolving thought about the shortcomings of liberalism and the shortcomings of the civil rights movement as a product of it.

Kai Wright: Because it's this moment where it's no longer about Black people have been wronged and so that needs to be fixed and it's more about this vague principle of race shouldn't matter.

Jelani Cobb: Right, because you can't really do anything to fix the conditions imposed upon Black people because we're supposed to adhere to a colorblind standard of the constitution. If that's the case then you mean there are lots of contentions that you can make about just how colorblind the constitution actually is, but if you are operating under that presumption, you're going to immediately run into a roadblock of actually correcting the situation that was created in the midst of all those years.

Kai Wright: It also seems like it connects to this other big idea he lands on that you've described. I want to hear you talk about is the notion that the gains that did come from the civil rights movement leading up to this Supreme Court case, they were not the result of a mass moral awakening amongst white people, but rather just a product of the convergence of our interests. What did he mean by that and why does it matter?

Jelani Cobb: Derrick Bell talks about what people would immediately say, it was a rather cynical estimation of what made the civil rights movement possible. Bell argued that Black progress had overwhelmingly been achieved in this society when it aligned with white interests and you can walk through the history of Black America in this way that Black people were emancipated because it was in the interest of the country to preserve the union.

Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party and many other northerners came to understand that they could not win the war and preserve the union without also emancipating the enslaved Black people in the South, and veto for the enfranchisement of Black men with the 15th Amendment, which was done as a counterbalance in the South against the solidly Democratic ex-Confederate population. With the civil rights movement, one of the dynamics there is that this also occurs against the backdrop of decolonization and the emergence of former colonial states as free countries in Asia and in Africa and in Latin America, and in the Caribbean.

This occurs in the context of geopolitical competition between the United States and the Soviet Union. It made racism in the US a geopolitical liability that at the same time that the US was trying to reach out and create diplomatic ties and outflank the Soviets in newly emerging nations which were overwhelmingly people of color. At the same time that was happening, there were Black people agitating for freedom at home and it looked bad. It was international liability. Derrick Bell argued that international affairs had as much to do with the timing of the civil rights movement as any domestic development.

Now, of course, the other narrative was that this was simply a moment in which the nation's moral conscience had matured and that there were individual people, which most certainly were, there were individual people whose hearts were changed and who came to understand the evils of racism. All things are true, but I think that Bell was talking more about the active ingredient, the element that allowed all these other things to come into existence, and he thought that overwhelmingly the Cold War was responsible for it.

Kai Wright: Can we dig into that a little bit more? Do you agree with Bell on this too? Because I think people hear that, okay, this was not about the fact that America had a moral maturation in the white people, in particular, had some kind of moral maturation it's just was cold realpolitik. Then your mind immediately goes to individual white people of course who did have a moral maturation.

Jelani Cobb: What's not really up for dispute anymore was that the Cold War was a factor in how the civil rights movement came about. I think that what people would argue would be relative degrees of influence. There were things happening in the United States, like one instance, an Indian diplomat in DC wandered into Virginia and was refused service because he was a dark-skinned person.

Then as these nations decolonize and as they achieve independence, they're politicians, they're ambassadors, they're envoys who are coming to Washington DC with their segregation. All these things are really very difficult and an embarrassment on the world stage. We also know that in the Supreme Court, people were very much aware of the international implications of Brown versus Board of Education when the case came to the court was actually heard twice but when the case was heard in the 1954 decision was handed down.

Also, for the presidency, if we think about the success of administrations even going all the way back to Truman in the 1940s, they're very much concerned about the way that the Soviets will use, any racial discord or any negative racial publicity from the United States to their propaganda advantage. These things are part of the ambient context in which the civil rights movement takes place and it certainly is a catalyst for the development of the movement.

Now, that said, there are important instances of people whose minds are changed. Stokely Carmichael, Kwame Ture told a story about a man who attacked him, physically attacked him during a civil rights protest, who later tracked him down and begged his forgiveness and said that he was just beholden to ignorance and hate and that he had come to see how wrong he had been.

I don't think that those things should be dismissed. There is a certain sepia tone to that narrative and a certain kind of romance to think that things just happened without there being any broader political considerations of how and why and when, and so on.

Kai Wright: Before we move on from this, why does it matter? Why does this distinction matter to Bell?

Jelani Cobb: Because I think that Bell is trying to, at its heart, trying to work through the durability of racism and what he comes up with is self-interest. We're clear, we understand the vested interests in racism and how people benefit from it. How white people benefit from a system in which they're at the top of the racial hierarchy. I think Bell was saying, "How do you reconcile that with these moments of advancement in progress?" It was like, "At some point it was more advantageous to part with the racial traditions of the country than it was to maintain them."

Also, I think in talking to students and young people, one of the things that I always point out is that most of the tremendous changes are the product of years or decades of work in the shadows. I think the implication of Bell's argument is that people have to work until there are these moments when people's interests align in these particular ways.

Kai Wright: I'm talking with New Yorker writer Jelani Cobb, about the true story behind the much-discussed phrase, Critical Race Theory. Up next, the generation of scholars who heard Derrick Bell's ideas and turned them into a massive intellectual movement, the one that's causing so much agita in right-wing media lately. I'm Kai Wright, stay with us.

[pause 00:33:00]

Welcome back. I'm Kai Wright and New Yorker writer Jelani Cobb is telling us the real story behind the phrase Critical Race Theory and the man whose work it grew out of, Derrick Bell. He was one of the architects of the civil rights movement's legal strategy but he eventually came to question the movement he helped to lead. By the 1970s, he'd become deeply skeptical of liberal ideas about how to achieve racial justice, but his critique didn't really find an audience until the next generation of legal scholars started thinking, "Huh, maybe he's got a point."

Jelani Cobb: Bell was really a kind of man in the wilderness at the beginning of his career. Certainly, people understood that law had been used in racist ways, but his approach to trying to understand how the law was complicit in these issues was not a wellspring of academic interest at that point. He published a case book Race, racism, and American law. He published it in 1970 and 1971 but by the 1980s this is the Reagan era, people are really worried that the advancements of the civil rights movement are being rolled back.

There is an increasing interest in the points that Derrick Bell had been trying to make, or the questions he had been trying to ponder. In early 1980s when Bell had gone to Oregon, Harvard failed to assign his class to anyone. A group of Black students were very concerned about whether or not these courses would just vanish in his absence and so they conspired to teach the course themselves and brought in different speakers and created a syllabus and so on.

That was the beginning of a cohort of people who coalesced, and they became the core group of Critical Race Theory scholars. Many of them are younger people, native and people of color. Kimberlé Crenshaw, who is very highly recognized law professor in her own right was one of these students at Harvard pushing to have this class organized and taught by the students themselves.

This group begins a wide ranging set of inquiries around discrimination, around anti-discrimination law, around the way that the law functions to bolster particular social relationships and hierarchies. Very much influenced by another group, the critical legal studies group, who were looking at the law and saying that it wasn't neutral, it's not objective, it's not this kind of distant arbiter of constitutionality but it is an animate, almost element of our society that reflects social interests. Critical Race Theory comes out of both of those tributaries. By the mid late 1980s, you begin to see the cornerstone scholarship that really defines the movement.

Kai Wright: I often think about that group of scholars as the beginning of the debate we're in today, still. It feels like so much of the current backlash from the right in particular is about trying to put that toothpaste back in the bottle about trying to rein those people back in. That's my big theory of the world over the last 30 years. Does that ring true to you?

Jelani Cobb: In a sense that the Critical Race Theory was really crucial to giving people a language to understand what was happening in the world around them. If we look at what happened in that time period, I think that it became a critical rubric for people to understand, "Oh, this is why we're seeing the schools resegregate in our society despite everything that happened in the 1950s and '60s. Oh, this is why we have anti-discrimination law on the books, but Black women are also still the last hired and first fired in ways that don't seem to be contravened by the existence of anti-discrimination law."

What are the premises that people are operating on? How faulty are those premises? How is racial hierarchy and racism able to manipulate and utilize those blind spots to its own advantage? I think what was refreshing about it was that these were things that people could see and they could recognize but it wasn't that easy to articulate what all was happening and why it was happening.

Kai Wright: How do you think that group of people changed academia and changed universities?

Jelani Cobb: For one, if we're just talking about legal studies, this creates a tremendous controversy and lots of dissension. For me, around the time when I first began to take things like this seriously, or pay close attention to it, Critical Race Theory was just everywhere.

It was one of the most prominent debates that people were having in legal academia. Over the course of subsequent years and decades, really, the ideas of Critical Race Theory came to be incorporated by scholars of history, scholars of literature, scholars of sociology, and recognizing in criminal justice and in all these different ways, seeing how this set of ideas could help explain the way that the world operated.

When I was talking with one of my students, if you forgive the cliché, I gave the example of the scene in the Matrix where Neo looks around and realizes that he can see the coding and he can read what's happening. I think that's what Critical Race Theory was trying to do for the law.

Kai Wright: One of the things that stood out in your article to me about Derrick Bell is that you were in conversation with him at the time that Barack Obama was campaigning and winning. Barack Obama was one of his students, I believe at Harvard. It wasn't a source of optimism for him, Barack Obama's campaign.

Jelani Cobb: It was not. I don't think Obama ever took Bell's class directly, but he did know Bell. As a matter of fact, at one of the rallies where Bell was explaining why he had to leave Harvard or take a leave from Harvard over their failure to hire or tenure any Black women, he was introduced at that rally by Barack Obama, who was then the president of Harvard Law Review. They knew each other.

In the context of this, having a conversation by this point in 2008, I actually knew Derrick Bell, not very well but we occasionally corresponded via email. In the course of exchange about James Baldwin, the prospect of having a Black president came up and he was not at all optimistic. He said that he thought that if Obama was elected, what we would see would be something that was like Brown versus the Board of Education or like the '64 Civil Rights Act that promised much delivered nothing and only assisted the country in moving closer to its premature demise.

That's a pretty close quotation of what he actually said. I remember reading that and being stunned. I'd always known that Derrick Bell was very skeptical but I felt like his skepticism had soured into fatalism when I read that exchange, and that remained my view until the worst stretches of the Trump era. When [unintelligible 00:41:13] I revisited that email and thought, "I don't have the same vantage point on this that I did when he wrote it a decade ago."

Then on January 6th, as I watched, mostly white mob, mostly white, mostly male mob climbing into the United States Capitol, and a brazen attempt to overturn an actual election. At that point, Derrick Bell's email seemed almost prophetic to me.

Kai Wright: Jelani Cobb writes for The New Yorker and his Dean of the Columbia University School of Journalism. We have a link to his New Yorker article on Derrick Bell in the show notes for this episode. Thanks for coming on Jelani.

Jelani Cobb: Thank you.

[pause 00:42:00]

Kai Wright: Before we wrap up this week, I want to check in on our ongoing project, the notes from America's summer playlist, and I'm joined by our producer Regina de Heer. Hey Regina.

Regina de Heer: Hi Kai.

Kai Wright: We are deeply underway in our listener generated summer playlist. The theme this year is music of our diasporas. Listeners have been sending us songs that represent their own personal stories of identity as part of some kind of diaspora. We're taking those submissions and we're making a Spotify playlist that listeners can stream right now.

Regina de Heer: Yes, it's available to stream right now. Just go to wnyc.org/playlist to listen. In our last installment, I added my own song to the playlist stability by RSR.

[MUSIC – Stability by RSR]

Kai Wright: It is a gem.

Regina de Heer: These are definitely [unintelligible 00:43:01] gets playlists. Kai, the real heartbeat of this project is the responses we're getting to our question, what is a song that represents your personal diaspora story? That can be any diaspora to be clear, whatever it is, what's a song that represents your connection to that community?

Kai Wright: We are including your voice recordings as part of the playlist itself. Listeners, when you go to wnyc.org/playlist, you can hear not only the songs but the stories behind the songs, which is really cool.

Regina de Heer: Exactly. I have a few of those submissions to give everyone idea of what they'll hear. First up, we heard from a listener named Junior who is based in Houston. Shout out Houston.

[MUSIC - Jean and Dinah by Sparrow]

Junior: My name is Junior. I was born in Trinidad and Tobago in 1974. A song that I can say is a song that I remember as a kid, it was by a calypso artist named Sparrow. The song was called Jean and Dinah. It's so weird from listening to Jean and Dinah and many other Calypsonians, when I was in a kid in the '70s and '80s growing up here in Houston, Texas, my older brother, he was four years older than me, I used to listen to Kool Herc, Ice Tea.

I bought the NWA first album when they first came out but I still go back to my original roots Jean and Dinah calypso artists Sparrow. Wow.

Kai Wright: Regina, calypso is specifically from Trinidad?

Regina de Heer: Yes. It began there and spread throughout the West Indies. It's actually a close relative to this West African music called Kaiso out of Nigeria. There's a really cold diaspora story there too. The next voicemail is from Tarek in Seattle, Washington. He started off his voicemail by sharing that growing up he really wanted to assimilate to be like the people he saw on TV and in movies. A few years ago, a sudden death in his family sparked an interest in exploring his own Palestinian culture.

Tarek: It wasn't really until my grandmother died in 2019 that I was thrust back to this world of culture that I had ignored my whole life. Oh, I have to like see this family members and all these people that I haven't seen in years. When I was in that room not being able to understand the Arabic, I realized what a mistake that I made. Ever since then, I've been trying to like reincorporate this culture back into my life.

The song I picked for this was, The Snake for Lana Lubany. It's so funny because ironically, I don't know how to say her last name, it's just a testament to like how far from this relationship that I am. I picked it because it was one of the very first massively popular US songs with Arabic in it. The way that it incorporated Arabic music so beautifully and naturally really spoke to me.

[MUSIC – The Snake by Lana Lubany]

Kai Wright: Oh, wow. Tarek, thank you so much for sharing that story. I'll also note that a lot of our voicemails are coming from people in an Arab diaspora community like Tarek, which is very great. I suspect that's because our first segment in this summer series was on music of the Arab diaspora. I do want to emphasize that we want to hear from everybody, whatever your diaspora story is, whatever diaspora you feel like is part of your story, it is very much welcome in this playlist.

Regina de Heer: That's exactly right. Also, I've been really blown away by the vulnerability and thought given to this assignment. Not going to lie, I've even gotten quite emotional a few times hearing the stories from our listeners. For example, here's a submission from Shaza who is originally from Syria.

Shaza: The singer is Édith Piaf and the song je ne regrette rien it's mean I don't regret anything.

[MUSIC – Non je ne regrette rien by Édith Piaf music]

It's because I've been through a lot in my life. I have to make a very big decision. Like because of the war in my country because of my divorce because I'm a single mom my girls had to live far away from me. Sometimes I had like a very big things happening in my life, very challenging ups and down and stuff. Sometimes I feel like, "Yes, I made good decisions." Sometimes I feel, "Oh no, I should not do that." I could have done better.

Then I realized that, "No, me, I'm not going to regret anything that happened in my life, good or bad. I'm not regretting any decision I made because at the end of the day, I think that what's happened with me make me the person I am now and make me strong, independent now," and I like it. This is what I tell my two daughters too.

[MUSIC – Non je ne regrette rien by Édith Piaf music]

Regina de Heer: By the way, it's worth pointing out that Édith Piaf is not herself Syrian but her music represents something to Shaza and I want to underline that's completely valid. Your song submissions can be anything. The point is that they mean something to you about your relationship to the diaspora.

To that point, the last voicemail I have for you is from Jenny. She shared that her Lebanese dad met her white mom in a nightclub parking lot in Tucson, Arizona. She has this vivid memory of getting to know her Lebanese side during her first trip to the region. It's attached to a certain song from a very famous movie. You may have heard of it, Titanic.

[MUSIC – My Heart Will Go On by Celine Dion]

Jenny: When I got to Lebanon and connected with my cousins for the first time, one of my cousins Ruba absolutely was obsessed with this movie. We're talking, I met her in a Titanic t-shirt, like there was a hand sewn pillow on my bed with the Titanic movie poster embroidered into it. Absolutely obsessed.

I remember sitting in my uncle's kitchen in my dad's hometown in Baalbek and finally getting permission to watch Titanic on this like little tiny VHS TV. I remember absolutely loving My Heart Will Go On by Celine Dion, obviously.

[MUSIC – My Heart Will Go On by Celine Dion] I was so excited to finally connect with my family and this cousin who was pretty close to my age over this American piece of cinema. To this day, whenever I visit, I always listen to the Titanic soundtrack and it reminds me of that day in my uncle's kitchen, having this moment with my cousins for the first-time watching Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio struggle to get on that little rickety door in the ocean.

[MUSIC – My Heart Will Go On by Celine Dion]

Kai Wright: Okay, Leo and Kate bringing together this Lebanese family. I love it. Okay, so Regina, remind everybody how do listeners get involved.

Regina de Heer: Yes. Listeners, we want to hear from you. Tell us what song represents your personal diaspora story. Go to notesfromamerica.org and look for the green record button to leave us a message. Start with your name and where you're recording from. Then tell us the name of the song you picked, the artist, and a short story that goes along with it. Feel free to include a little bit about your background as well.

Kai Wright: You can also stream the playlist now. Remember you just go to wnyc.org/playlist right after you listen to this. We're going to keep updating it throughout the summer with your submissions and thank you, thank you, thank you for being willing to be part of this project. Notes from America is a production of WNYC Studios.

Follow us wherever you get your podcast and on Instagram @noteswithkai. Theme, music, and sound design by Jared Paul. Our team also includes Billy Streams, Karen Frillman, Regina de Heer, Rahima Nasa, Kousha Navidar and Lindsay Foster Thomas, André Robert Lee is our executive producer, and I am Kai Wright. Thanks for listening.

[00:52:12] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.