The True Story of Critical Race Theory

( ASSOCIATED PRESS / AP Images )

Regina de Heer: Have you ever heard of critical race theory or the debate about it?

Female 1: I haven't, unfortunately.

Regina: Have you heard about Derrick Bell?

Female 1: No, I haven't, but definitely, if I could write down his name, I'll Google him. Yes, I think critical thinking is very important.

Regina: Critical thinking or critical race theory?

Female 1: Critical race theory? Oh, it's critical race theory?

Regina: Critical race theory, have you ever heard of that?

Female 2: No. What happened?

Regina: Have you heard of critical race theory?

Male 1: Who?

Regina: Critical race theory. Have you ever heard of that term before?

Male 1: What is it?

Female 3: I don't know. I feel so silly because I know there was a point where I knew what it was. Isn't it just examining your actions or what you see through a race-conscious lens, maybe?

Female 4: Yes, I'm not sure how I would define it. I feel like I kind of know what it is but I really don't know how to put it into words properly, yes.

[music]

Kai Wright: This is the United States of Anxiety. I'm Kai Wright. You know what? It's totally understandable if you cannot define critical race theory. Honestly, if you've not been to law school or had some form of graduate education in the humanities, it's really unlikely you would have even heard the phrase before this spring. That's about when critical race theory became the latest jumble of words loaded into the pull-string doll of right wing media.

Another incantation to fear for those who feel threatened by a changing America. Phrases like, "Defund the police," or, "Antifa," are-- For you old timers out there, remember Benghazi? Benghazi, Benghazi, Benghazi. Or even death panels, remember that one from the early ObamaCare debate? Anyway, the thing is that this one is particularly sad to me because critical race theory is actually rooted in a really thought-provoking set of ideas.

It has a fascinating backstory. We're going to learn that story tonight. I'm not taking calls, but there will be a chance for you to chime in at the end of the show, so stick around because you're going to help us figure out the next show we do in this really interesting space. Okay. Our guide through the history of critical race theory is New Yorker writer and Columbia Journalism School professor, Jelani Cobb. He wrote about this history in a recent piece of the magazine and he joined me for the full show. Hey, Jelani, thanks for coming on.

Jelani Cobb: Thank you.

Kai: I learned a new phrase that I do love, reading your piece. You talked to the legendary, to my mind, legendary legal scholar and Nation columnist, Patricia Williams, who said what's been done to critical race theory is, "Definitional theft." I love that phrasing. Explain what she meant by it.

Jelani: She meant that they had taken a term that existed, that had a definition, and completely usurped it and stolen, effectively, the name, critical race theory, and applied it to a completely different set of ideas that have nothing to do with what the originators and the scholars who founded this field were really thinking about.

Kai: You quote the right wing activist, Christopher Rufo, who pretty clearly spells out the plan of attack for that definitional theft on what he calls 'the brand' of critical race theory. Who is this guy, and why is what he said important to understand before we even get into this conversation?

Jelani: He's really the person who's at the center of the recent uproar about critical race theory. He's a right wing political operative, and he said, literally, that he wanted to take the brand and "freeze it as an association with a whole array of negative things in people's minds." This was done, really, as a counter offensive after millions of people saw that video of George Floyd's death, and really were driven to literature, to research, to history, to try to understand how this could come about, what society are we living in.

That really unsettled, I think, people who were in the right wing part of the political spectrum. This was an attempt to discredit critical race theory, but really a more substantial attempt to discredit a whole body of anti-racist scholarship that people had turned to after George Floyd's death.

Kai: I think it's so interesting that he even used the word 'brand.' This is a set of ideas and he called it a brand.

Jelani: Yes, I think that's one of the more grotesque parts of modern life, that everything is a brand. I'm old enough to remember when people were trying to establish a good reputation, and now people want to establish a brand. It's importing that the language of marketing into our daily lives, and in this case into our intellectual lives and into social policy and activism. Critical race theory is not a brand.

It's a movement with distinct intellectual roots, with parameters and specific questions about the legacy of civil rights, discrimination and anti-discrimination law, and the ways in which racial hierarchies have been able to reassert themselves despite the best intentions and successive wave of attempts to reform.

Kai: Of course, the irony of all this is that both critical race theory, specifically, and the man whose work it grew out of, this was all a critique of mid century liberalism, and really the civil rights movement itself. I'll be honest, Jelani, I didn't fully appreciate that before reading your piece. I actually suspect there are a lot of people on all sides of the political spectrum out here talking about this idea, who don't actually know what it is and where it came from.

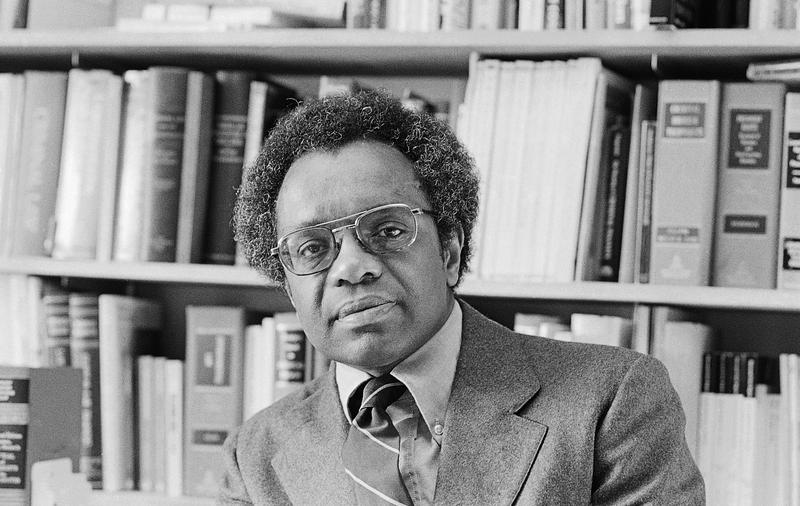

That's why we wanted to sit down with you. You tell this life story of Derrick Bell. Introduce him in a few sentences for those who haven't spent their lives in the halls of academia. Who was Derrick bell?

Jelani: It's really hard to introduce Derrick Bell in a few sentences but I'll do my best. Derrick Bell was a activist. For the first part of his life, he was a legal activist who risked his life to file and fight desegregation suits in Mississippi between 1960 and 1966 when he worked for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

The second part of his career was in academia as a law professor, where he began pioneering work that, essentially, critiqued what he had done as an activist lawyer. That sent him down the route of questioning the underpinnings of the legal and, to a certain extent, the social strategies of the civil rights movement, and the ways in which liberalism had failed to uproot racism in American society.

Kai: I think you did it well. Let's unpack all of that. His first job was out of law school for the Department of Justice. This is 1957, I believe, but he's a registered member of the NAACP and the DOJ wants him to quit that group. Instead, he resigns.

Jelani: Yes. Which becomes a theme in his life. Derrick Bell was the first Black attorney in the Civil Rights Division at the Department of Justice. Being hired there, in 1957, was no small deal. This was a very prestigious and significant position that he had attained but he was a member of the NAACP. When they told him that he would have to quit, he just decided that he would quit but he wasn't going to quit what they thought.

He wasn't going to quit the organization, he was going to quit the DOJ. This came up again and again in his career. Subsequently, he quit as the Dean of the University of Oregon Law School because they refused to extend the job offer to an Asian female candidate, who was the third person on a list after two prior candidates, both white men, had declined the position.

Kai: It suggests, and you talked to people who knew him who suggest this, a certain personality.

Jelani: Certainly, right.

Kai: Talk about that, it's more than just his ideology. He sounds like he was a person who was a bit of an absolutist, I guess.

Jelani: Yes, I think he was an absolutist about matters of principle. In the third instance where he quit yet another job, and even possibly more prestigious a job than the DOJ, was when he quit in 1990, Harvard Law School, over its failure to hire and tenure a Black woman faculty member or any women of color. He said at the time, he gave a speech, where he said that he could not afford to walk away from that job, but he also felt that he could not, in good conscience, tell his students to live out their principles if he failed to do the same.

You just find that as a theme in his life. The one last thing I'll say is that one of the things that stands out to me about him in having learned more about him in the process of writing this was that he really was a person who was driven by integrity and driven by his sense of principle. He countenanced the beliefs and arguments of people who thought differently than he did, and encouraged people to express themselves.

He was by no means a zealot or an ideologue in any kind of way but he was trying to follow, I think, the most honest intellectual path that he was capable of.

[music]

Kai: Well, after he quits the Department of Justice in 1957, he lands a job at the NAACP instead. This is a really interesting moment in the history of Civil Rights, 1957. This is right after the end of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The NAACP has litigated and won in the Supreme Court, and he steps into that. In some ways, this is perhaps maybe the most idealistic time for the movement. Now, help situate us in time for the civil rights movement that he steps into at that time?

Jelani: It's really a time of harvest, especially the legal part of the movement. Beginning in the 1930s, when Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall were filing these cases, across the country, and laying the groundwork for what happens in the 1950s, it was lonely work swimming against the tides, trying to get these desegregation suits past these judges.

By the 1950s, they reached a point where all of a sudden they have the wind at their back, it's a mix, my metaphor here. They are really moving, there's obviously, Brown versus Board of Education, Montgomery Bus Boycott lawsuit, and then they begin essentially inoffensive across the south filing thousands of desegregation suits, many of which were overseen by Derrick Bell.

By the way, he's very much influenced by Thurgood Marshall. Has a young Lieutenant in the Air Force. He sees the Brown versus Board of Education decision and is immensely inspired by it, that's part of the reason that he goes to law school. When you look at the moment that he arrives at the NAACP legal defense fund, it's one of the most exciting and fertile moments in that movement's history.

Kai: He's at the center of it all, but it sounds like he's not entirely sure about the work he's doing, and whether it's helping, which is really hard to wrap your head around. You tell the story of a school desegregation case that comes to him from Mississippi, explain that case and what happened.

Jelani: Yes. At the time, which I think is what makes it more dramatic is that Bell really did think that he was doing the right thing. His misgivings and his second thoughts really occurred years later. There is a Rosenwald School in the beginning at the turn of the 20th century. A philanthropist by the name Julius Rosenwald, allotted money to build 5,000 schools for Black students across the south, a tremendous act of philanthropic giving that transformed many communities.

There was a Rosenwald School in a place called Harmony, Mississippi. The school's board, the all-white school board was opting to close the Rosenwald School there, the Harmony school. That prompted a group of activists to form an NAACP chapter and to start talking about what they could do to keep the school open. A woman who was the vice president of the chapter, a woman by the name of Winson Hudson reached out to Derrick Bell and said, "We would like to keep the school open."

Bell described himself as being astounded because he said, "You do know that we are trying to desegregate schools, so we can't fight a law suit to reopen a segregated Black school." The fact of the matter is that the community was much less interested in desegregating the school than they were in keeping what they felt to be a quality Black school open in their community.

This is the point in which there's a divergence that Derrick Bell comes to actually time and again, in his work, a divergence in the interests of the NAACP and the plaintiffs who they represent, but who ultimately do wind up representing these families in Harmony, Mississippi, and suing to have the schools there integrated which happens. It gives you a sense of how people who appear to be operating on the same side, are really sometimes operating at odds, or have different interests.

Kai: What did he do with that? You said, he notices this divergence between somebody like Winson Hudson, who's like, "No, what all I want is quality education for Black kids. I don't care about the integration piece of it," and then NAACP wants the integration piece of it. That leads to this larger critique, what did he take from the divergence that he saw there?

Jelani: Well, in order to understand how he evolves, we have to add in a little bit of history, which is there's lots that happens. We can just summarize it by saying many of these school systems are integrated, at least in theory, which in turn sparks a mass exodus of white students from the school systems, into what they called segregation academies. They effectively ensure that Black students would be going to overwhelmingly Black schools even after so-called integration had taken place.

In turn, many of the public schools, which were never great in the south, never really wonderfully funded, became even more poorly funded because there was less reason for white taxpayers to be invested in what happened in public schools. Derrick Bell looks at this play out in the 1960s and 1970s. He tells Winson Hudson, who he sees at a conference, he says, "I'm not sure I gave you the right legal advice." She tells him, "I'm not sure you did either," which is a fascinating moment.

The fact of the matter is, two decades after Brown versus Board of Education, you are still seeing Black students going to overwhelmingly Black schools. We should also add an asterisk here or a footnote here, to say that the problem was never that they were going to overwhelmingly Black schools. The problem was that as long as Black students were segregated in one particular set of schools, it would be easier to underfund those schools, it'd be easier to shore up inequality.

The ideal of integration was that, if you put Black students and white students in the same schools, they would have to fund them because you would not want to deny a quality education to white students either, if it meant denying it to Black students. This is one of the ideals that was at play, but it ultimately plays out very differently. By the 1970s, Bell, he is really beginning what becomes a multi-decade effort at reassessing what happened in the course of the civil rights movement. That reassessment is really the cornerstone of critical race theory.

[music]

Kai: Up next, where Derrick Bell's mind when he began that reassessment of the movement. Plus, what do you think critical race theory is? Can you define it? We'll check on some of your answers. I'm Kai Wright. This is the United States of Anxiety. Stay with us.

[pause 00:17:32]

Kai: Welcome back. This is the United States of Anxiety, I'm Kai Wright. This week, New Yorker writer and historian, Jelani Cobb, is telling us the true story of critical race theory and the man whose work inspired it. Before we learn more of that history from Jelani, earlier this week, our producer Regina de Heer, went over to Union Square in Lower Manhattan, where there's a new set of memorials.

These three huge bronze sculptures of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and the late Congressman John Lewis. All these names are now markers in political time, names that became synonymous in 2020, with a mass reckoning. Their deaths and their lives inspired people to want to learn more about the structures of racism in this country. People turned to scholarship.

As Jelani argued before the break, right-wing political operatives responded by trying to demonize that scholarship, and particularly by picking a fight over whether and how racism is taught to kids. Beyond Fox News' echo chamber, is that really working? Regina figured she'd hang out by these new monuments, and just see what people are talking about.

Regina de Heer: We are standing here in front of the monument honoring George Floyd, John Lewis, and Breonna Taylor. Do you think that racism and topic of race is something that should be taught or addressed in school?

Karen: I believe it should be discussed. I think because there are so many discriminations out there from a very, very early age before it becomes a problem that they should be some unification. I've been able to identify different races, how different we are, but also how similar we are. I think a lot of racism is a learned behavior.

Regina: What do these monuments mean to you? Here in Union Square, one of the most famous parks in New York City, what does it mean to you? Anything?

Desmond: It's beautiful, but we need more than statues. You know what I'm saying? We need reparations. We need better schools and rehabilitation centers, and shelters, and all kinds of other good stuff. These statues are good and all that, but until all the police are held accountable, it really don't mean nothing really too. You know what I'm saying? With no disrespect. I hope nobody take that the wrong way because I'm only fighting for my people.

Matt: Before this whole George Floyd thing, I've been living in this country for four years and I'm a white guy, long and blue eyes, and even at this moment, I feel very bad when George Floyd was killed, but I think this whole Black Lives Matter thing also mutated more negative forms. I never ever received any racial attacks, but now, right now, this year I already received five racial attacks by Black people, and they're trying to provoke something, for example, walking down the street and trying to spit on my shoes.

Because all of this, it made me to switch sides. I was a Democrat, but I actually stand on different side and I think it's law and order supposed to be because this is a country where multi-races are living in one. It should be a good, peaceful area to live for everyone.

Regina: Do you think educators should be discussing or teaching about race in schools?

Tiani: People just don't understand on racism out here, especially in New York City. It's not right, and I feel like people should really discuss this in schools instead of just discuss stuff that really don't matter. Stuff that matter is racism and how we need to treat each other. We all bleed the same color, so we all should stick together. It should be no division.

Desmond: Everybody should be taught about the horrific things that have taken place in history when it comes to racism, so we can know about it and learn from it and learn how that's not allowed in today's generation. It's in the present. We're not going to act like racism stopped years ago and it's not a part of our history no more because racism still takes place in our history today.

Regina: Is there a way to teach about race and racism?

Parrish: It has to be delicate. Everybody takes everything so personal. Even the communication skills is lacking. It seems like the more advanced we became with technology, the less we became social individuals, but we can talk about problems all day long, but it's about solutions.

Regina: Have you ever heard of the term critical race theory?

Stephan: I have heard of it. I do know about the controversy, but I really don't care about it. That's white people fighting what white people think, and it doesn't make sense for even Black people to join that.

Regina: What if I told you that critical race theory was actually developed by a Black man at Harvard?

Stephan: If it's relevant, its relevant. If we want to make it relevant, we can make it relevant, but that shouldn't even be a fight. If it's something we want to implement, then let's implement it. That's it, we are not going to fight or debate about it with white people in white schools. If you want to have that debate, you could have that debate. As far as I'm concerned, we're entitled to have it in the schools. I think, right now, we're at the point where we need to come up with our own schools and our own education system.

[music]

Kai: Listening to that last guy there, I hear something similar to what Winson Hudson was trying to tell Derrick Bell and his NAACP buddies. In fact, when they sued to integrate schools in Mississippi, remember she said she wasn't particularly invested in debating integration versus segregation. She was interested in getting resources for Black students.

That distinction was initially lost on Bell, but it began to trouble his thoughts about the pioneering civil rights work he'd done. Jelani Cobb says that in the early 1970s, those misgivings became the foundational ideas of today's critical race theory. They were in fact disturbing ideas.

Jelani: Right. He also felt that, if you were to institute as massive a set of changes as the civil rights movement brought about, and still wind up with outcomes that were reminiscent of what happened before the civil rights movement, then it meant that racism would not be easily uprooted from American society. It's around this point that he begins saying that we should consider racism to be a permanent feature of American life which was enormously controversial when he first said it.

People believed, and one of the ethics of the civil rights movement had been that the society could change and that people could uproot racism. Here is a person who was a soldier on the front lines of the movement saying, "I don't think this is ever going to change. I think this is always going to be a permanent feature of American life." This was just not really said. These were things you didn't really hear from the crowd that Derrick Bell was associated with. For a time, it created tensions even in some of his personal relationships as people wondered if he had just become jaded.

Kai: To be honest, that is my perspective that it's a permanent part of American society. I never really understood, and I've said it for many years. I didn't understand that I was in a line of thought that started with Derrick Bell.

Jelani: Yes. I think a lot of people have that experience. A lot of people have that experience that we have ideas that are attributable to what Derrick Bell was trying to figure out. We have had an easier route to drawing some of these conclusions precisely because he wasn't so invested in his own glory. A lot of people would've just recounted their tales of great courage and achievement and never had the intellectual honesty to question whether or not this actually made the difference you were trying to make. Derrick Bell was one of the people who was willing to do that.

Kai: At this point, we're in the mid '70s or so that he starts to recognize this. It's a controversial idea at that time. There was another big Supreme Court case you point out around that time that shaped his thinking. That's in 1978, and it's the Supreme Court case that reaffirmed the purpose of affirmative action in college emissions, but did so in a way that troubled Bell. How so?

Jelani: He's talking about the Bakke case which is famous. It's the famous reverse racism argument. It is that a man by the name Allan Bakke, who had applied to medical school at University of California system twice and had been rejected, but found that there were Black students who had lower scores who had been accepted, sued and said that he had been a victim of reverse discrimination.

The Supreme Court decision on it narrowly preserved affirmative action on the grounds of diversity and saying that it was permissible if you were diversifying the population, et cetera. That's been one of the main buzzwords ever since. Derrick Bell was incensed and deeply troubled by this, and it really distills a lot of what his uneasiness had been. That, in essence, the court was responding to specific racially intended policy and legislation that had excluded Black people from institutions of higher learning, but they can only respond to it with a tool of color blindness.

He does not think that what happened to Allan Bakke in the admissions process is the equivalent of what happened to Black people who were turned away from universities, irrespective of what their scores were. He said that, as long as we are making these two things equivalent, as long as we're engaged in this false equivalency, we'll never actually be able to achieve racial progress. That's why I think Bakke really is at the cornerstone of his evolving thought about the shortcomings of liberalism and the shortcomings of the civil rights movement as a product of it.

Kai: Because it's this moment where it's no longer about Black people have been wronged, and so that needs to be fixed. It's more about this vague principle of race shouldn't matter.

Jelani: Right. Because you can't really do anything to fix the conditions imposed upon Black people because we're supposed to adhere to a color-blind standard of the constitution. If that's the case, which there are lots of contentions that you can make about just how colorblind the constitution actually is, but if you are operating under that presumption, you are going to immediately run into a roadblock of actually correcting the situation that was created in the midst of all those years.

[music]

Kai: It also seems like it connects to this other big idea he lands on that you describe and I want to hear you talk about is the notion that the gains that did come from the civil rights movement leading up to this Supreme Court case, they were not the result of a mass moral awakening amongst white people, but rather just a product of the convergence of our interests. What did he mean by that and why does it matter?

Jelani: Derrick Bell talks about what people would immediately say was a rather cynical estimation of what made the civil rights movement possible. Bell argued that Black progress had overwhelmingly been achieved in the society when it aligned with white interests. You can walk through the history of Black America in this way that Black people were emancipated because it was in the interests of the country to preserve the union.

Abraham Lincoln and the Republican party, and many other northerners came to understand that they could not win the war and preserve the union without also emancipating the enslaved Black people in the south. Ditto for the enfranchisement of Black men with the 15th amendment which was done as a counterbalance in the south against the solidly democratic white ex-confederate population.

Jelani: With the civil rights movement, one of the dynamics there is that this also occurs against the backdrop of decolonization and the emergence of former colonial states as free countries in Asia and in Africa and in Latin America and in the Caribbean.

This occurs in the context of geopolitical competition between the United States and the Soviet Union, and so it made racism in the US a geopolitical liability, that at the same time that the US was trying to reach out and create diplomatic ties and out flank the Soviets in these newly emerging nations which were overwhelmingly people of color. At the same time that was happening, there were Black people agitating for freedom at home and it looked bad, and so it was a international liability.

Derrick Bell argued that international affairs had as much to do with the timing of the civil rights movement as any domestic development. Now, of course, the other narrative was that this was simply a moment in which the nation's moral conscience had matured and that there were individual people which there most certainly were. There were individual people whose hearts were changed and who came to understand the evils of racism.

All those things are true but I think that Bell was talking more about the active ingredient, the element that allowed all these other things to come into existence and he thought that overwhelmingly the Cold War was responsible for it.

Kai: Can we dig into that a little bit more? I mean do you agree with Bell on this too? I think people hear that, they say, "Okay, well this was not about the fact that like America had a moral maturation and that white people in particular had some moral maturation." It just was cold real politic. Then your mind immediately goes to individual white people, of course, who did have of a moral maturation.

Jelani: What's not really up for dispute anymore was that the Cold War was a factor in how the civil rights movement came about. I think that what people would argue would be relative degrees of influence, but there were things happening in the United States. One instance in Indian diplomat in DC wandered into Virginia and was refused service because he was a dark skinned person.

Then as these nations decolonize and as they achieve the independence, their are politicians, their ambassadors, their envoys who are coming to Washington DC where there's segregation, and all these things are really very difficult and an embarrassment on the world stage. We also know that in the Supreme court, people were very much aware of the international implications of Brown versus Board of Education when the case came to the court, it was actually heard twice.

When the case was heard in the 1954 decision was handed down, also for the presidency, if we think about the success of administrations even going all the way back to Truman in the 1940s, they're very much concerned about the way that the Soviets will use any racial discord or any negative racial publicity from the United States to their propaganda advantage. These things are part of the ambient context in which the civil rights movement takes place and it certainly is a catalyst for the development of the movement.

Now, that said, there are important instances of people whose minds have changed. I mean Stokely Carmichael, Kwame Ture, told a story about a man who attacked him, physically attacked him, during a civil rights protest who later tracked him down and begged his forgiveness and said that he just beholden to ignorance and hate and that he had come to see how wrong he had been.

I don't think that those things should be dismissed, but there is a certain CPA tone to that narrative and a certain romance to think that things just happened without there being any broader political considerations of how, why and when and so on.

Kai: I mean before we move on from this, why does it matter? Why does this distinction matter to Bell, that we understand that it wasn't this moral awakening, but rather these interests, this real politic, why is that an important distinction?

Jelani: I think that Bell is, at its heart, trying to work through the durability of racism and what he comes up with is self interest. We are clear. We understand the vested interests in racism and how people benefit from it, how white people benefit from a system in which they're at the top of a racial hierarchy. I think Bell was saying, how do you reconcile that with these moments of advancement in progress? It was like, well, at some points, it was more advantageous to part with the racial traditions of the country than it was to maintain them.

Also, I think in talking to students and young people, one of the things that I always point out is that most of the tremendous changes are the product of years or decades of work in the shadows. I think the implication of Bell's argument is that people have to work until there are these moments when people's interests align in these particular ways. That is something that allows you to have a sense of when progress may occur.

Kai: I'm talking with New Yorker writer, Jelani Cobb, about the true story behind the much discussed phrase, critical race theory. Up next, the generation of scholars who heard Derrick Bell's ideas and turn them into a massive intellectual movement. The one that's causing so much agita in right-wing media lately. I'm Kai Wright stay with us.

[music]

Kousha Navidar: Hey, everyone. This is Kousha, I'm a producer. Thanks for sending us your voice messages and emails. We love hearing from you. Here's one we received about last week's episode when Kai talked about refugees and Haiti. Remember, you can always talk to us, just email us a voice memo or a message. The address is anxiety@wnyc.org. I hope you're having a great day, talk to you soon.

Susan: My name is Susan and I live in Manhattan. In October of 1956, a sudden revolution broke out in Hungary. I was 12 years old. My family horridly packed some belongings to flee the country and we were running through the forest when we heard rifles behind us. We left all our suitcases on the forest floor and luckily we made it to Austria. We were welcomed by the Austrian government, they provided safe shelters and food.

We had a choice of what country to immigrate to, many countries opened their doors to Hungarian refugees and that is how we arrived in New York City in Christmas of 1956. I have only compassion for the tens of thousands of refugees now fleeing troubled countries. I think everyone should have a chance to have a new life. Thank you.

[music]

Kai: Welcome back. I'm Kai Wright and New Yorker writer Jelani Cobb is telling us the real story behind the phrase, critical race theory, and the man whose work it grew out of, Derek Bell. He was one of the architects of the civil rights movement's legal strategy, but he eventually came to question the movement he helped to lead. By the 1970s, he'd become deeply skeptical of liberal ideas about how to achieve racial justice, but his critique didn't really find an audience until the next generation of legal scholars started thinking maybe he's got a point.

Jelani: Bell was really the man in the wilderness at the beginning of his career. Certainly, people understood that law had been used in racist ways but his approach to try and understand how the law was complicit in these issues was not a wellspring of academic interest at that point. He published a case book Race, Racism and American Law. He published it in 1970 and 1971, but by the 1980s this is the Reagan era, people are really worried that the advancements of the civil rights movement are being rolled back.

There is an increasing interest in the points that Derrick Bell had been trying to make or the questions he had been trying to ponder. In the early 1980s, when Bell had gone to Oregon, Harvard failed to assign his class to anyone. A group of Black students were very concerned about whether or not these courses would just vanish in his absence and so they conspired to teach the course themselves and brought in different speakers and created a syllabus and so on. That was the beginning of a cohort of people who coalesced and they became the core group of critical race theory scholars.

Many of them are younger people. Many of them are people of color. Kimberly Crenshaw who was very highly recognized law professor at her own right, was one of these students at Harvard pushing to have this class organized and taught by the students themselves. This group begins a wide ranging set of inquiries around discrimination, around anti-discrimination law, around the way that the law functions to bolster particular social relationships and hierarchies very much influenced by another group, the critical legal studies group who were looking at the law and saying that it wasn't neutral.

It's not objective, it's not this distant arbiter of constitutionality, but it is an animate almost element of our society that reflects social interests. Critical race theory comes out of both of those tributaries. By the mid late 1980s, you begin to see the cornerstone scholarship that really defines the movement.

Kai: I often think about that group of scholars as the beginning of the debate we're in today still. It feels like so much of the current fight, the current backlash from the right in particular is about trying to put that toothpaste back in the bottle, about trying to reign those people back in. That's my big theory of the world over the last 30 years. Does that ring true to you?

Jelani: In a sense that the critical race theory was really crucial to giving people a language to understand what was happening in the world around them. If we look at what happened in that time period, I think that it became a critical rubric for people to understand, "Oh, well, this is why we're seeing the schools resegregate in our society despite everything that happened in the 1950s and '60s. Oh, this is why we have anti-discrimination law on the books, but women, Black women are also still the last hired and first fired in ways that don't seem to be contravened by the existence of anti-discrimination law."

What are the premises that people are operating on and how faulty are those premises and how is racial hierarchy and racism able to manipulate and utilize those blind spots to its own advantage? I think what was refreshing about it was that these were things that people could see and they could recognize, but it wasn't that easy to articulate what all was happening and why it was happening.

Kai: How do you think that group of people changed academia and changed universities?

Jelani: For one, if we're just talking about legal studies, this creates a tremendous controversy and lots of dissension. For me, around the time when I first began to take things like this seriously of people's attention to it, critical race theory was just everywhere. It was one of the most prominent debates that people were having in legal academia.

Over the course of subsequent years and decades really, the ideas of critical race theory came to be incorporated by scholars of history, scholars of literature, scholars of sociology, and recognizing in criminal justice and all these different ways, seeing how this set of ideas could help explain the way that the world operated.

When I was talking with one of my students, if you forgive the cliché, I gave the example of the scene in the Matrix where Neo looks around and realizes that he can see the coding and he can read what's happening. I think that's what critical race theory was trying to do for the law.

Kai: One of the things that stood out in your article to me about Derrick Bell is that you were in conversation with him at the time that Barack Obama was campaigning and winning. Barack Obama was one of his students, I believe, at Harvard.

Jelani: Yes.

Kai: It wasn't a source of optimism for him, Barack Obama's campaign.

Jelani: It was not. I don't think Obama ever took Bell's class directly, but he did know Bell. As a matter of fact, at one of the rallies where bell was explaining why he had to leave Harvard or take a leave from Harvard over their failure to hire or tenure any Black women, he was introduced at that rally by Barack Obama, who was then the president of the Harvard law review.

They knew each other. In the context of this, having a conversation by this point 2008, I actually knew Derick Bell, not very well, but we occasionally corresponded via email. In the course of a exchange about James Baldwin, the prospect of having a Black president came up, and he was not at all optimistic. He thought that, if Obama was elected, what we would see would be something that was like brown versus the board education, or like the '64 Civil Rights Act that promised much, delivered nothing and only assisted the country in moving closer to its premature demise.

That's a pretty close quotation of what he actually said. I remember reading that and being stunned. I'd always known that Derrick Bell was very skeptical, but I felt like his skepticism had soured into fatalism when I read that exchange. That remained my view until the worst stretches of the Trump era.

Again, I revisited that email and thought, "I don't have the same vantage point on this that I did when he wrote it a decade ago." Then on January 6th of this year, as I watched mostly white mob, mostly white, mostly male mob climbing into the United States Capitol in a brazen attempt to overturn an actual election, at that point, Derrick Bell's email seemed almost prophetic to me.

[music]

Kai: Jelani Cobb writes for The New Yorker, and teaches in the Journalism Program at Columbia University. We'll have a link to his New Yorker article on Derrick Bell and the show notes for this episode. Thanks for coming on Jelani.

Jelani: Thank you.

[music]

Kai: That conversation is a lot to digest, no doubt. Listeners, I said, at the top of the show, that we weren't going to be taking calls, but that we would have a question for you at the end. I want to turn to that now. I'm joined by our producer, Kousha Navidar. Kousha, welcome to the show.

Kousha: Thanks. Hi.

Kai: What do you think when you hear this conclusion Derrick Bell arrived at, that racism is permanent. Do you agree with that? What do you tell take from it?

Kousha: I'm pretty persuaded by Derrick Bell. I would have to agree and I would love to be proven wrong, but it certainly, especially recently has felt like racism is permanent in America. What do I take from it? Well, I think of what Jelani was talking about with how he describes work to his students, the idea that you have the hand that you need to play and you work every single day to try and make sure that you are doing the work that needs to be done to push progress forward. I take solace in that, it's not defeatist so much as empowering to figure out what happens.

Kai: What does that mean in a real way, though, Kousha, for you in your everyday life? Those are fancy words and heady ideas, but what does that actually mean doing in your life?

Kousha: I've tried to make it part of my professional life with the content that I make, trying to make sure that it educates, entertain and inspires. I think also, I don't know if this is still too heady, but I try to check myself a lot, make sure that I think about what my perspective is and what I might be lacking when it comes to national issues or even things that are going on in my community. There's a lot of humility, I guess, that I try to approach at the world.

Kai: For me, it makes me struggle just with the idea of pluralism, just like the idea of engaging with white people, frankly, on a lot of days and white power structures. It can be really a dispiriting thing once you reach that conclusion. Like you say, it can also be an empowering thing because I have clarity, so it's, "Okay, this is the work that's in front of us."

Kousha: I would rather do it than sit by.

Kai: We are having this conversation because we want you listeners to have this conversation, because you tell our listeners what we would like to have them do.

Kousha: This is a great opportunity to put what we've listened to into action, so here's our ask. Please go to a friend, go to someone in your life, and just ask them a couple of questions. The first one, ask them, "Do you think racism is permanent in America?" and hear what they have to say. If they say, "Yes, racism is permanent," ask them a follow-up question, "What does that mean for our individual actions?" If they say, "No, racism is not permanent," then ask them, "Why hasn't it been fixed yet, and what is left for us to do?"

Kai: Do that. Do those things and then send us what you found. Send us reflections on the conversation. You can just send it in an email or you can, even better, record a voice memo and send it to us, or even, even better, you can record the conversation itself. Send it to anxiety@wnyc.org. That's anxiety@wnyc.org. Kousha and I, and the whole team thank you very much for that. It's going to really shape what we do next with these ideas that Jelani and Derrick Bell have brought us.

Kousha: Yes. The best part so far has been hearing from listeners, so thank you so much.

[music]

Kai: United States of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios. Our theme music was written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band, mixing by Jared Paul. Our team also includes Emily Botein, Regina de Heer, Karen Frillmann, and Kousha Navidar, and I am Kai Wright. You can keep in touch with me on Twitter @kai_wright. Of course, join us for the live show next week, Sunday at 6:00 PM Eastern. You can stream it at wnyc.org or tell your smart speaker, "Play WNYC." Until then, thanks for listening. Take care of yourselves.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.