How Congress Made the Opioid Crisis Worse

[PROMOS/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. Brooke Gladstone is out this week. I’m Bob Garfield.

This week, at a press conference held with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, the President took the opportunity to set the record straight on his urgent commitment to his major policy goals, like health care.

[CLIPS]:

PRESIDENT TRUMP: We are getting close to healthcare. It will come up in the -- early to middle part of next year.

BOB GARFIELD: Economic growth.

PRESIDENT TRUMP: I’m gonna be surprising some people with an economic development bill later on.

BOB GARFIELD: And the opioid crisis.

PRESIDENT TRUMP: We’re gonna have a major announcement, probably next week, on the drug crisis and on the opioid massive problem.

BOB GARFIELD: When it comes to the opioid epidemic, “next week” has been a long time coming, since at least his presidential campaign.

PRESIDENT TRUMP: It’s an unbelievable problem that we have all over this country. If I win, I’m gonna stop it. You watch what happens.

BOB GARFIELD: And more recently, since August, when President Trump officially deemed the crisis a “national emergency.”

PRESIDENT TRUMP: The opioid crisis is an emergency, and I’m saying officially right now it is an emergency. It’s a national emergency. We’re gonna spend a lot of time, a lot of effort and a lot of money on the opioid crisis.

[END CLIP]

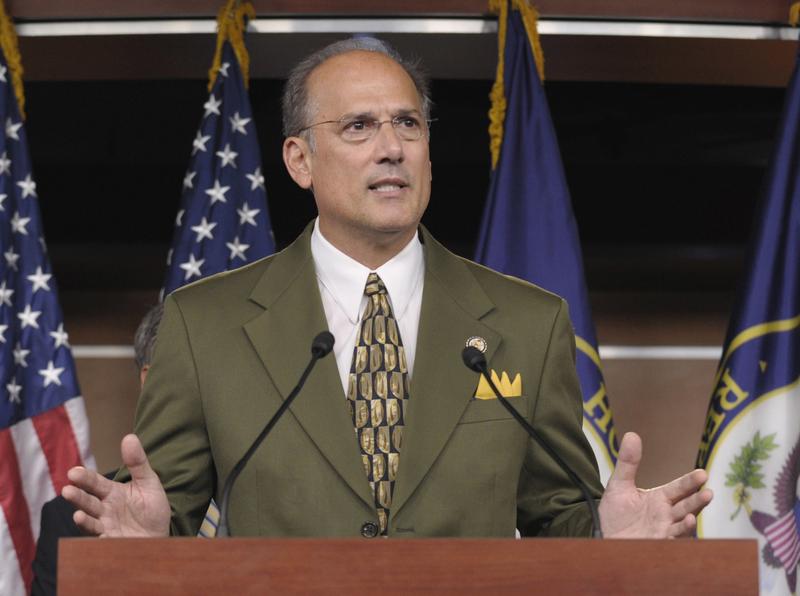

BOB GARFIELD: Except that no expenditure of time, effort or money managing this national emergency is evident, as the death toll gets ever larger. Experts estimate that last year 64,000 people died from drug overdoses, more than half from heroin, fentanyl and prescription painkillers like OxyContin. Meanwhile, the Washington Post and 60 Minutes jointly reported last weekend that the government's ability to crack down on elicit painkiller sales has been seriously compromised, thanks, in part, to Trump's erstwhile drug czar pick, Pennsylvania Congressman Tom Marino.

[CLIPS]:

MALE CORRESPONDENT: As the opioid epidemic reaches new heights, a law sponsored by Marino last year made it tougher for the Drug Enforcement agency to stop millions of narcotic pills from flooding the streets.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: In the midst of the worst drug epidemic in American history, the US Drug Enforcement Administration's ability to keep addictive opioids off US streets was derailed.

BOB GARFIELD: After that story broke, Marino was out.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: President Trump has just tweeted moments ago. He said, Congressman “Tom Marino has informed me that he is withdrawing his name from consideration as drug czar.”

BOB GARFIELD: A triumph of journalism? Maybe, but the much, much larger problem still remains and, for that, journalism may have at least a little bit to answer for.

Lenny Bernstein is one of the reporters behind the Washington Post/60 Minutes investigation. Lenny, welcome to the show.

LENNY BERNSTEIN: Thank you very much.

BOB GARFIELD: Let's start with the basics. There are illicit ways to get large quantities of opioids, ways that benefit drug manufacturers and distributors and retailers, even if they are doing nothing actively wrong. How is it done?

LENNY BERNSTEIN: It's pretty simple, actually. If you are an illicit user of opioids or a dealer, you get a bogus prescription from a cooperating physician, often for cash. And the folks out there who are using these drugs know which pharmacies to go to. And, often for cash, you will be given these opioids.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, so the DEA is, obviously, on to these rackets and has shut down various pharmacies and distributors over the years that were, at a minimum, facilitating the black market. And specifically keeping an eye on this activity were a couple of guys named Joe Rannazzisi and Linden Barber. Here’s Rannazzisi speaking about drug distribution companies in his interview with 60 Minutes.

[CLIP]:

JOE RANNAZZISI: This is an industry that's out of control. What they want to do is do what they want to do and not worry about what the law is. And, if they don't follow the law, in drug supply people die. That's just it. People die.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: So Lenny, tell me how, over the past decade, these guys went about their business.

LENNY BERNSTEIN: First, they warned these companies. They called them all in, in 2006, 2007, and they said, look, under the law, you're supposed to contact us if you see unusual patterns, unusual amounts or unusual frequency of these drugs being ordered by pharmacies, hospices, nursing homes, hospitals, anyplace that uses them. And after a few more warnings, the DEA started to go after these distributors who declined to follow the law.

BOB GARFIELD: Which distributors, in particular?

LENNY BERNSTEIN: The “big three,” Amerisource Bergen, McKesson and Cardinal Health. All three are in the top 25 largest corporations in America. But also a lot of small distributors, some that you would call mom-and-pop distributors. There was one in 2007 that was sending drugs off to internet pharmacies. They put 90 million pills into circulation in the black market. There were only a handful people who worked for that company. All they did was send out pills. And for some of these companies, the most egregious ones, they went in there with immediate suspension orders and shut ‘em down that day. And that began the tussle between the drug distributors and the DEA.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, now you mentioned “under the law” and the law dates to 1970. It says that distributors and pharma companies and retailers are responsible to be vigilant for irregularities that cause an “imminent danger to communities,” and that turns out to be important language because in around 2014, this consortium started lobbying Congress to push through a new law called the Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Act, cosponsored by two Republican members of Congress, Tom Marino and Marsha Blackburn, Marino, Pennsylvania, Blackburn, Tennessee. What did the bill nominally set out to do and what did it actually achieve?

LENNY BERNSTEIN: The distributors always felt and claimed that the phrase in the law “imminent danger to the public health” was too vague. How do we know when we see it? Well, the DEA had given them a number of definitions and a lot of regulations and they also said, common sense, please. If a pharmacy is ordering 20,000 pills in February and 100,000 pills in May, something’s going on. Stop the flow of the drugs and alert us and we can look into it.

The Ensuring Patient Access Act, the first version brought by Tom Marino, was sold as a way to make this phrase less vague, help the distributors understand their responsibilities and to prevent the disruption of pills to legitimate users, people who need them for cancer pain and end-of-life diseases. Now, the law doesn’t do anything like that. There is nothing in the law that ensures patient access. The Marino bill also, because of the language, would have made it virtually a criminal standard before the DEA could move in. That is, the DEA would have had to show intent on behalf of these companies, that they actually intended to do something wrong. That's impossible. And it began to work its way through Congress.

BOB GARFIELD: And that odyssey in a moment, but I guess it will come as no surprise to anybody that there were hundreds of millions of dollars put into the lobbying effort on the part of this pharma consortium and also campaign contributions in the millions to, among others, and [LAUGHS] you could knock me over with a feather, Tom Marino and Marsha Blackburn, the sponsors of the bill, both from communities that have been heavily wracked by the opioid epidemic.

LENNY BERNSTEIN: Correct. The distributors and the various companies involved in this and some other associations together spent about $102 million lobbying on this and other bills. The way the reports come in you can't tell exactly what they spent on each bill. And similar companies gave $1.5 million in campaign contributions to the 23 people who cosponsored this law. You don't give campaign contributions in Washington, most of the time, if you're not expecting something back.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, at a moment in history when an epidemic is killing more people than car wrecks and the Vietnam War, you would think that people would be alert for language in the bill that made it harder for the DEA to enforce.

LENNY BERNSTEIN: The House bill was fought by the DEA and the Justice Department pretty vehemently. They said, this is fixing a problem that doesn't exist, this is going to take away our authority, this is the greatest diminution of the attorney general’s authority in many decades. Joe Rannazzisi, who you mentioned earlier, by holding the drug companies’ feet to the fire, had greatly antagonized them. He’s a man with a temper. He ticked off a number of politicians.

BOB GARFIELD: Including [LAUGHS] Congresswoman Marsha Blackburn, one of the cosponsors at a hearing on what was then just a bill.

[CLIP]:

JOE RANNAZZISI: Sixteen-thousand six-hundred and fifty-one (16,651) people in 2010 died of opiate overdose, okay, opiate-associated overdose. This is not a game. We’re not planning a game here.

CONGRESSWOMAN MARSHA BLACKBURN: Nobody is saying it is a game, sir. We’re just trying to craft some legislation…

[END CLIP]:

BOB GARFIELD: Oh, they crafted some legislation, all right, and ultimately the bill passed, again, unanimously, in April of 2016. President Obama signed it, without any real public protest. The DEA, itself, had stopped fighting the good fight. And the media's coverage sounded like this.

[CHIRPING SOUND]

In other words, not a word about this legislation because all eyes were focused elsewhere on our insane presidential campaign. How did something so destructive happen with so little resistance, ultimately, and with so little notice from the outside world?

LENNY BERNSTEIN: Well, that’s a terrific question, and that's the question that still needs answering as a result of our story. It was not until a couple of months later, when Mr. Rannazzisi, who is now almost a year out of government, began sounding the alarm, that various newspapers started looking at this law.

BOB GARFIELD: But there was something else that was going on that is, in many ways, more disturbing than cynical legislation by members of Congress getting money from the pharma lobby. And that is what happened within DEA, itself. Earlier, I mentioned Linden Barber who was a DEA lawyer who had been a point man for a lot of the enforcement actions against distributors and retailers but he left government and went to work for?

LENNY BERNSTEIN: He became one of the top, if not the top, drug industry lawyers. And he brought with him a knowledge of the DEA's regulatory efforts, their scheme, their thinking, and he knew where it was strong and he knew where it was weak. He had an impact inside the DEA and cases began to slow down.

An investigator named Jim Geldhof, who was trying for two years to bring a case against Miami-Luken for pouring millions and millions and millions of pills into West Virginia, and every time he thought he had enough, the DEA legal office would send him back for more, more experts, more evidence, more interviews, more transcripts, and this was happening not just to Jim Geldhof but to all kinds of investigators in all kinds of investigations. And it is very clear that for reasons of over-caution or belief in what Linden was saying, the DEA was slowing cases down.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, earlier we observed that the attention of the press and the public was entirely dominated by Trump and Trump coverage. Only now is it getting any attention. What have we as an institution done wrong?

LENNY BERNSTEIN: Well, I was one of the people who was out there not reporting this story. I was [LAUGHS], I was on this beat and didn’t have a clue that this law was being debated on Capitol Hill, discussed inside the DEA and the Justice Department. It’s not a great thing. Almost exactly a year ago, we did mention this law in part of a very large story about the problems at DEA. None of that broke through the Trump coverage, none of it.

Here, we have broken through the Trump barrier. I would have to credit the collaboration with 60 Minutes. It's a very powerful platform. The outrage that this could be passed during an epidemic of that magnitude has finally hit home.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, there was one immediate effect of your reporting, and that was the effect on the President’s nomination for the new drug czar. In the great tradition of Trump appointees being foxes to guard their particular hen houses, he had nominated Tom Marino. The author of the Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Act was going to be the drug czar, and he, well, officially withdrew, but let's just say presumably was disinvited from the nomination. Apart from that, I wonder if anything else is going on, like, for example, consideration of amending or repealing the law altogether?

LENNY BERNSTEIN: There is a movement on Capitol Hill to re-examine the bill. Some Democrats have called for repealing it. Remarkably, pharma, the big drug manufacturing lobby, has called for repeal. Others want to amend it. Chuck Grassley, the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, has said he will hold an oversight hearing to see if the bill really is harming DEA. So there is some movement for repeal, but I would say that it is far from certain that anything will change.

BOB GARFIELD: Lenny, thank you.

LENNY BERNSTEIN: My pleasure.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Lenny Bernstein covers health and medicine for the Washington Post. Coming up, how narcotics became opioids and addiction became a national epidemic.

BARRY MEIER: There was a new drug popping up on the streets called OxyContin and its producer was promoting this drug as something that was less addicting.

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media.

[PROMOS/MUSIC UP & UNDER]