David Remnick: This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. One fine day in August 1974, I believe I was dangling off a ladder, painting houses in New Jersey, I heard on the radio in my pocket something that seemed truly dangerous. A guy had strung a wire between the two buildings of the Old World Trade Center, the famous Twin Towers, and he was walking between them, a quarter of a mile up in the air.

Philippe Petit: I'll tell you what, I have a very queasy feeling in my stomach right now, because I'm at, let's see, 1,500 feet, and up here at 1,500 feet or in that area, there is somebody out there on a tightrope walk between the two towers of the World Trade Center, right at the tippy top.

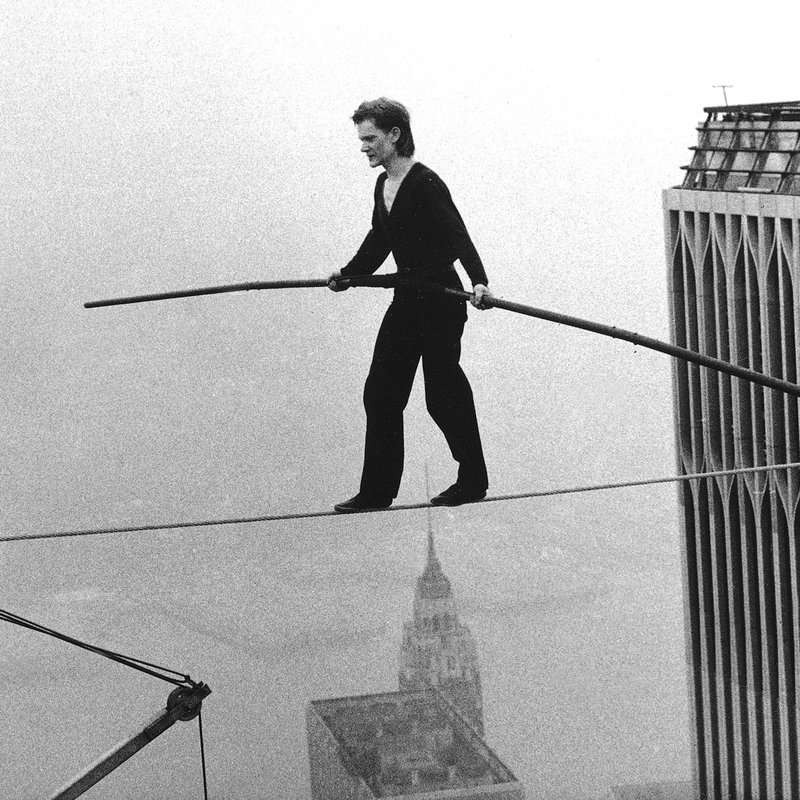

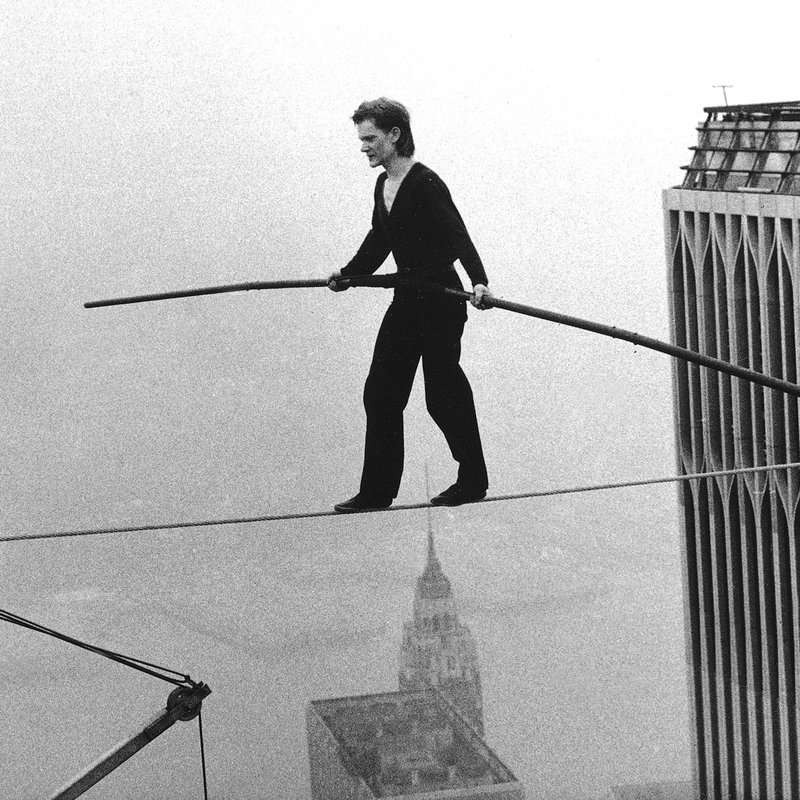

David Remnick: The man's name was Philippe Petit, a high-wire artist from France, just 24 at the time, and that astonishing feat took place 50 years ago this week.

Philippe Petit: It was a performance, but a strange kind of performance because my audience could not be invited in advance, and also, they were a quarter of a mile below me. But still, it was a performance, but it was also a very intimate dialogue with me and the birds, me and the sky of New York, me and the Twin Towers. I never thought of the consequences. It was not part of my thinking.

David Remnick: When Petit was profiled in The New Yorker, the piece was called Alone And In Control.

Parul Sehgal: In a battered trunk in a small room on an obscure street in Paris, a room he still rents, although he's rarely there, Petit has squirreled away his dreams: maps and pictures of eminences and promontories, skyscrapers and other buildings around the world he longs to conquer. He is drawn to the grandiose. On August 7, 1974, Petit set a record, still unsurpassed for the loftiest walk over a city street. He surveyed the tower surreptitiously for several months beforehand. Three friends, including a photographer named Jean-Louis Blondeau, flew from Paris to help him. At the time, the top ten floors of the towers were being finished, and thousands of electricians, carpenters, and deliverymen flowed in and out of the buildings along with the office workers.

No one noticed anything unusual about two young men, Blondeau and an accomplice dressed in business suits, who entered the North Tower late in the afternoon of August 6th. About the same time, that Petit and the third friend, disguised as deliverymen, rode an elevator to the hundred-and-fourth floor of the South Tower, the topmost reachable by elevator, on their way to the roof with equipment concealed in packages marked "Electric fence." After carrying the cable which weighed 440 pounds up a hundred and eighty steps to the floor below the summit, itself no mean accomplishment, they hid until the sole guard nodded off.

In the dark, they sneaked onto the unfinished roof. Almost simultaneously, Blondeau and his accomplice emerged from their hiding places on the North Tower. At midnight, Blondeau shot an arrow with a thin line attached over the gap, a distance of a hundred and forty feet. Unfortunately, the arrow landed on the lowest and farthest beam of a 15-foot metal truss that sloped downward from the roof. Petit was now faced with an enormously dangerous situation. He had no choice but to climb down the truss and retrieve the arrow.

Once back on the roof, he hauled over lengths of heavier and heavier line, and attached the cable to the last one. Blondeau pulled the cable back to the North Tower and secured it to a steel beam. Petit attached his end to a grip hoist, a powerful device for drawing the cable tight that was attached to a beam. All this labor took seven hours. Working furiously against the dawn, they tied guy lines onto the truss to steady the wire.

Just as light came into the sky, Petit climbed down the truss one last time. In a narrow corridor underneath, between the tower and its outer skin, he changed into a black sweater, black pants, and wire-walking slippers. At 7:15 AM, as the city began to awaken, Petit took out a yellow grease pencil and drew his symbol and wrote his name and the date on a beam of roof, and started his walk. Word spread rapidly. "An unbelievable story has just arrived. I don't believe it," one broadcaster said. "Report of a man walking across the World Trade Center buildings on a tightrope."

In the street, 1,350 feet below, a quarter of a mile, throngs of people gathered. They abandoned their cars to gawk, and traffic snarled. Port Authority police, responsible for the towers' security, raced onto the roofs with emergency squads from the city police. Petit never glanced at them. He glided back and forth on the wire, holding his long balancing pole. He lay on the wire. He knelt, bowed, danced, and ran. He sat down and watched a seagull fly beneath him.

Finally, after nearly an hour, he ended his performance, walked back onto the South Tower, and was handcuffed. When he reached the street, people cheered him and tried to shake his manacled hands. They booed the police. “Why did you do it?” reporters shouted. In English, more accented than it is now, Petit replied, "When I see three oranges, I juggle; when I see two towers, I walk."

David Remnick: That's an excerpt from Gwen Kinkead's profile of Philippe Petit. Read for us by the New Yorker's, Parul Sehgal. That high-wire walk between the Twin Towers took place a half-century ago this week, a few hundred feet from where I'm sitting now.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.