BOB GARFIELD: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. Every time news breaks about a mass shooting we see a flurry of downloads of a one-page postable sheet we wrote called, the “Breaking News Consumer’s Handbook. It happened in May of this year, after the shootings near the campus of the University of Santa Barbara, and then again in early June, after another campus shooting in Seattle, and two weeks later, after a high school shooting in Oregon and even, weirdly, after that Malaysian passenger jet was downed in Ukraine. Why? Because the news after a mass death is invariably wrong in key respects. Our “Breaking News Consumer’s Handbook” first ran in September of 2013, after a shooting at the DC Navy Yards. Here’s Wolf Blitzer.

WOLF BLITZER: Someone dressed in a black top, black jeans, what does that say, if anything, about a possible motive or, or whatever? Can we begin to draw any initial conclusions? And I want to alert our viewers, sometimes these initial conclusions can, obviously, be very, very wrong.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The initial coverage of the mass shooting at the Washington Navy Yard by contractor Aaron Alexis bore all the earmarks of classic reportage in the midst of these all-too- frequent horrors. It stunk.

[SIREN SOUNDING IN BACKGROUND]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: We’re looking at a situation possibly involving multiple shooters here at the Washington Navy Yard.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Wrong.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: It’s believed that whoever this gunman is, a man in his fifties who is carrying three weapons, a handgun, a shotgun and an assault rifle…

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Wrong about his age, wrong about the assault rifle.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Earlier today, some media outlets were tweeting out that the shooter was a named Raleigh Chance.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, that is dangerously wrong. Breaking news, whether of a violent storm or a vicious gunman, creates chaos and confusion. That’s a given. But what the news media do in the face of it, that’s a choice. And they pretty much make the same choice in every medium, on every platform, in every era.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Rumors ran rampant. At first, it was thought that Vice President Johnson had also been shot in the attack.

REBECCA GREENFIELD: During the JFK assassination, if you listen to the radio broadcasts, they sound as uncertain as Twitter reporters sound when they’re reporting if he’s alive, if he’s dead.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Rebecca Greenfield writes for The Atlantic Wire.

REBECCA GREENFIELD: A reporter in Dallas goes back and forth on it. At one point, they report that there were three shooters there. It goes all the way back to the reporting of the Titanic, even. There were false telegraphs saying that the Titanic hadn’t sunk and that it was on its way to Halifax, safe.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The new media environment means everyone gets to report or disseminate news of disaster. Some report well, some badly, but all are retweeted. So listen up. Some of this is on you.

ANDY CARVIN: When a breaking news situation is happening, you really should pay attention to certain keywords that members of the media may use because they mean very distinct things.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Andy Carvin is the senior strategist on NPR's Digital Desk.

ANDY CARVIN: So, for example, if they say, we're receiving reports that XYZ has happened, that should suggest to you that some of their sources are claiming something but it's not necessarily confirmed, whereas if they then say, we can confirm that such and such has happened, that means that they feel that their sourcing is strong enough that they can go out on a limb and claim that this is an actual fact. And there are all sorts of words that they may use in between, such as, “It appears that such and such has happened,” so they’re feeling somewhat confident but they still haven’t necessarily confirmed it either.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What about, “CNN has learned”?

ANDY CARVIN: One of the things that you will sometimes hear during breaking news is the phrase, “CNN has learned” or “”NPR has learned.” While it may not seem like a big deal, it’s their way of saying, we have some sort of scoop. So, on the one hand, it could mean that they do have a scoop and they’re the first ones to confirm something, or they’re going out on a limb and reporting something that no one else has felt comfortable reporting yet.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: A shooting where NPR got it initially wrong was reporting that Congressperson Gabby Giffords had died.

[CLIP]:

NPR SPOKESWOMAN: In a fast-changing news situation, with conflicting reports, we should have been more cautious. NPR news apologizes to the family of Representative Giffords and to you, our listeners.

[END CLIP]

ANDY CARVIN: Which is why it's also important to listen to whether or not they're claiming what the source is, so, for example, if they say, “We’re receiving information from law enforcement sources or law enforcement officials,” if they’re not going on record with that law enforcement official’s name, then it’s still essentially speculation, whereas if they say, “Officer such and such, at a press conference five minutes ago, said XYZ,” that means the officials have gone on the record with their names and the information that they have.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Unnamed sources led CNN up the path to

perdition by wrongly claiming a suspect had been apprehended in the Boston Marathon bombing. And unnamed officials wrongly fingered Ryan Lanza, the actual shooter's brother, as the gun man at Sandy Hook.

But named officials maligned the citizens of New Orleans in the wake of Katrina. In the first hours of mayhem coverage, trust no one. News consumers longing for certainty should just learn to live with the pain. As Carvin says, “Mark our words,” meaning the media's words, and learn from experience, even if we don't.

IAN FISHER: First off, they should be wary about names that come out because often shooters are using different IDs or often the law enforcement officials are wrong.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Ian Fisher is Assistant Managing Editor for Digital Operations at the New York Times.

IAN FISHER: Be wary of organizations that blindly quote other organizations without solid sourcing. They aren’t taking a very big chance in doing that. They can always say, “Oh, that was them, not us.” Another thing is there’s almost never a second gunman.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It's like House on the TV show, saying, “It’s never lupus.”

IAN FISHER: Right. It’s, [LAUGHS] it’s never lupus. There’s almost never another gunman.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Craig Silverman, author of the Poynter Institute’s Regret the Error blog, has just written a piece which he plans to run every time there's a crisis. It's called, “This is My Story about the Breaking News Errors That Just Happened.”

CRAIG SILVERMAN: And it just basically will fit pretty much any breaking news error situation in the future.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Okay, so what happens every single time?

CRAIG SILVERMAN: So, misidentification of people, usually of victims, of perpetrators, very consistent. We’ll often see mistaken numbers, in terms of the number of victims, in terms of the number of perpetrators and that kind of thing, as well. Sometimes location is incorrect, where something originated, where something is happening now, mistakes also related to images, so fake images that are portrayed as real or images that were taken previously and sort of find their way to be presented as if they’re new. So that's very consistent, as well.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: As you know, big news brings out the fakers.

CRAIG SILVERMAN: Absolutely, and this is a really important thing for both journalists and for people consuming media in these moments to realize, is that there are lots of hoaxsters who know that in this moment people are just grabbing onto whatever image they can find. So they might Photoshop something and send it out. What we commonly see in, [LAUGHS] in weather situations is now what I call the street shark -

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

- where people will claim to see in a flooded street or highway a shark swimming.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

So, beware of street sharks.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So who should we trust?

CRAIG SILVERMAN: Well, a little bit of no one and a little bit of everyone. People on the ground, that’s always your preferred source. Can - have they actually seen it with their own eyes, are they actually there and do they know the area, really, really important.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But not guaranteed. I'm tempted now to play another montage here, of bad reporting of the Boston Marathon bombing, the Sandy Hook shooting, the Oregon mall shooting, the Aurora, Colorado shooting, the Virginia Tech shooting and Columbine.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

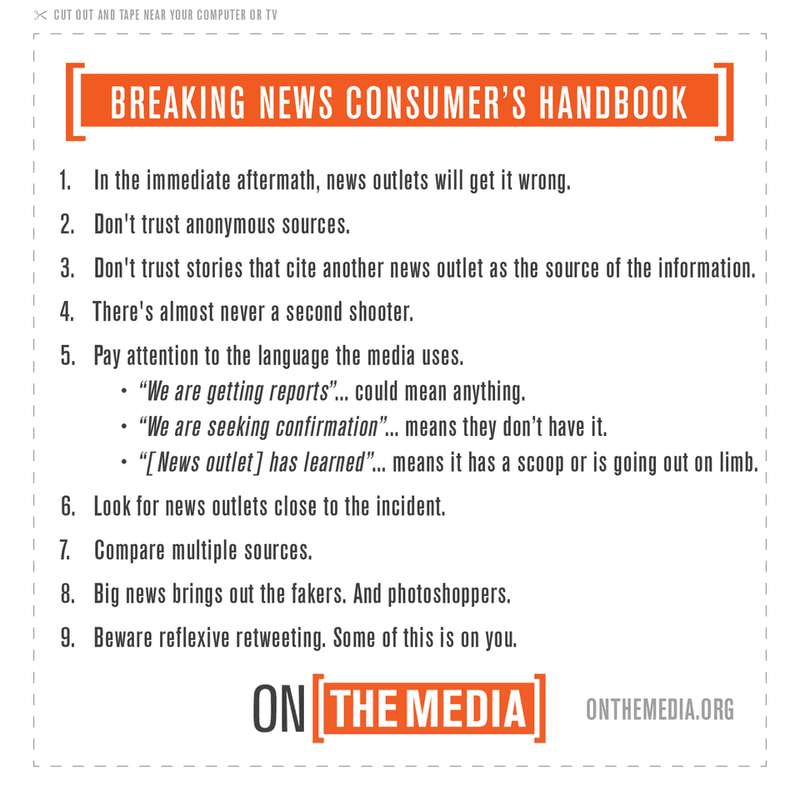

But I won't because the exercise would be more depressing than illustrative. Instead, we’ll put a chart on our website to post by your TV or radio or computer to consult when next confronted with a blood-saturated lead, because innocent people are shattered by guns but also by the buckshot of frenzied media, social media, included.

Take note of the words: “We’re receiving reports,” “an unnamed official says,” “another news outlet reports,” “experts speculate,” and, of course, “second gunman.” Mostly, they’re just buckets of blather deployed to fill that aching void. So print out our little chart. And may you never need it. But you will.