Black Music’s Most Memorable Moments With Emil Wilbekin

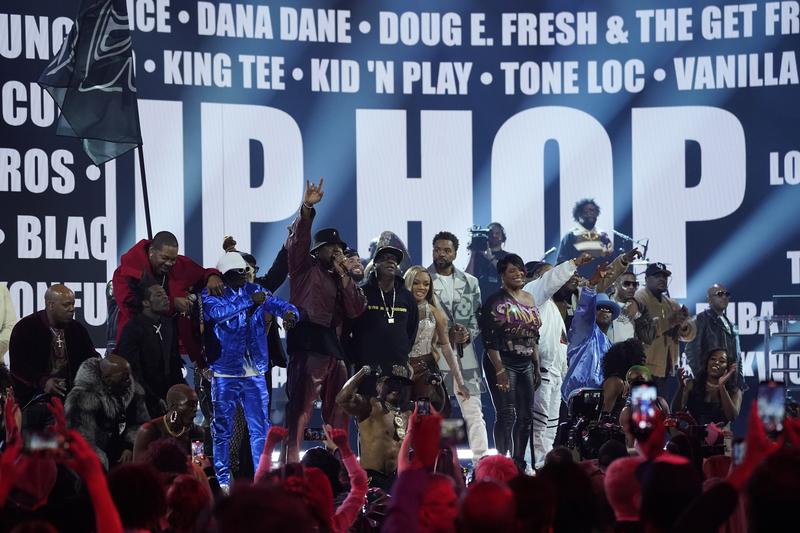

( Chris Pizzello / AP Photo )

[music]

Kai Wright: Notes from America has a deep interest in Black History all year round, you know that. We do also take note of Black History Month, and this year, we're thinking about it in the present tense. Throughout February, we'll bring you a series of conversations we're loosely calling Black History is Now. We're going to meet people doing cool things in Black spaces who think about their work as part of a continuum. Like it grew out of something that came before, it's trying to feed something or someone that's going to come after.

Emil Wilbekin is one such person, the Grammys are tonight, and it's worth thinking about just how dominant both Hip Hop and R&B are in today's global music market. Industry data suggests these genres easily combined for the largest market share, at what point a few years back Nielsen data showed 8 out of the 10 most streamed artists were rappers. Emil Wilbekin had a front-row seat for the era in which the seeds of that commercial dominance were planted, the early 1990s, a time when the success of a few massive Black artists, people like Michael Jackson, Prince, and Tina Turner opened the commercial door for this eruption of unapologetically Black popular culture.

Emil Wilbekin: There were Black fashion designers or Black fashion models, there was movies and TV. We were very, very present, and it was exciting. It was exciting time to be Black. Those was exciting time to see yourself represented on all platforms of media.

Kai: Emil helped build one of the most important platforms for showcasing that talent. He was one of the founding editors of Vibe Magazine, which was created by Quincy Jones in 1992 to chronicle the moment. Vibe was where a lot of people who became synonymous with '90s music. I mean, Mary J. Blige, Smith, Biggie. It's where they made their glossy debut into popular media.

Emile was part of Vibe's team throughout the decade and went on to serve as its editor in Chief, where he won a National Magazine Award or recognition that few people back in 1992 could have imagined for a magazine about Hip Hop. He's still writing about music and culture these days, and he's leading a project called Native Son, which builds community among Black queer men.

I asked Emil to situate his own life's work in the continuum of Black music history, starting with a TV show that shaped his dreams as a little boy in the early '70s.

[music]

Emil: I mean, Soul Train, in my household was a ritual every Saturday morning. We would have brunch, which we actually called brunch, which is fun.

[laughter]

It's like [unintelligible 00:03:08]. We had brunch, and my mother would cook, and we would sit there as a family and watch Soul Train. It was just a cultural ritual. It was a Black ritual. It was inspiring. It was like Saturday church for us.

Kai: As a kid watching that, what was capturing your imagination?

Emil: Oh, I mean. For me, being the creative kid that I was, it was everything from the music, the choreography and dancing, and then the outfits. I mean for me, it was like a plethora of creativity and Black brilliance. Just what wasn't inspiring when you watch Soul Train, right?

Kai: And of course, Don Cornelius.

Emil: The Don Corne-- and the Scrabble Board.

Don Cornelius: Don Cornelius. Hey there, and welcome aboard. You're right on time for another magnificent ride on the Soul Train.

Kai: Talk to me about him and his place in this cultural history.

Emil: I think Don Cornelius from me, really represents a Black shepherd of culture. He really believed in holding space for us to see ourselves. Black music has always been regulated to the sidelines, not given credit for being the first sound of rock and roll or having the most incredible voices that then uplift everyone else, we were always in the back.

For Don Cornelius to have this vision to televise a show that brought the music to life, that made us the superstars, the centerpieces, we were the first act, the second act, and the third act, right, and we were able to dance to our own music. We let other cultures then to share in that revelry because that's what Black people do, and to own that space and own that representation of Black art. I think that's what I give Don Cornelius credit for.

Kai: Why was the television part of it important? I'm thinking about the Grammys and these big TV moments, why was that crucial?

Emil: I mean, television then was the future. American Bandstand and Dick Clark, they all have these dance shows.

Dick Clark: From Philadelphia, it's time for America's favorite dance, from the American Band.

Emil: White teams would go on there dancing to Black music, but we never had a platform where we could see ourselves dancing to our own music. I think televising it gave it more power, and it reached a broader audience.

[music]

Kai: Soul Train inspired a young Emil Wilbekin. After a break, we'll learn how he and his colleagues at Vibe, then built another platform for bringing a new kind of Black music to a broader commercial audience. Stay with us.

[music]

Kousha: Hey, everyone, this is Kousha. I'm a producer. A few weeks ago, we did a special live show at the Apollo to honor Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Now, as part of that conversation, we asked some high schoolers what the phrase Young, Gifted, and Black meant to them. Here's one response we got from a listener named Michael.

Michael: It stands out to me because when you're young and gifted and Black, your soul is intact, is a message behind the song itself. I'm just blessed to be Black, Young, Gifted, and my soul is intact, so I love it. Thank you for asking for that song. It was amazing. It was beautiful.

The world has been cruel to the Blacks and to the African Americans, but we're staying strong at what we believe in. Talent is us. We are the world. I just, I love it. I love it. Thank you so much.

Kousha: Thank you, Michael. Thanks to everyone who's sending us messages. Now, you can hear that full episode, including the song Michael mentioned. Just check out the episode called the legacy of MLK Jr. is to be Young, Gifted, and Black. If you have something you want to say, send us a voice message. Just go to NotesfromAmerica.org and click on the green button that says start recording. You can also see more notes like Michael's on our Instagram feed. Our handle is @noteswithKaiWright, thanks. Talk to you soon.

[music]

Kai: It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright. This week we're beginning a series we're loosely calling Black History is Now. I'm talking with Emil Wilbekin, one of the founding editors of Vibe Magazine in the early 1990s, about how Soul Train laid a foundation for his own life's work. I asked Emil about the creation of the Soul Train Awards in 1986. I came across this quote from Don Cornelius, he said at the time, they were asking him about why he was creating it, and he said, "We tend to get taken for granted, we tend to get ignored as a group of creative people. Black Music is too big and too powerful not to have its own award show."

Emil: That's fun.

Kai: To me it's a harder idea to understand that in 2023, I think maybe then the 1986 reality he's describing. I mean, there are many challenges for Black artists today, but in a world of Beyonce and Jay Z, not to mention Lizzo and Lil Nas X, I think it's hard to really grasp what he's talking about there. Can you help people understand what role the Soul Train Awards was filling in the culture?

Emil: I think for us, it was really filling this void of you didn't see us front and center on award shows. We may perform, we may present, but not in a way where it was how our music, our audience, our community and I think it's something that back then was the big deal. This is around the time too, of music videos really coming into play. It's a parallel path of the music videos and what MTV was doing, but MTV still wasn't showing a lot of Black music.

There wasn't a place to see ourselves projected in this way and then celebrated and then celebrated by our own. I think that's what made the Soul Train Awards so special because it's our people, it's for us by us and honoring us, right?

Kai: Yes. It makes me think about other big Black-led TV moments and music, like we have to talk about Motown 25, I still have such a clear emotional memory of that broadcast. I was 10 years old, but the moment of Michael Jackson coming out in that glove and a hat, and debuting the moonwalk.

[music]

Do you have a memory of that?

Emil: Yes, and it's like you can never unsee it because when we talk about Black magic, that's what I think of when I think from a cultural perspective. What he was doing almost didn't feel human because the way he was moving, it was so smooth. The music, the outfit and he literally took everyone's breath away.

[applause]

[music]

Kai: This got Emil and I talking about other moments in which Black artists made really disruptive appearances in mainstream TV shows, like the Grammys and the Oscars. A beautiful one was at the 1988 Grammys, when Opera superstar Luciano Pavarotti canceled at the last minute and they had to get Aretha Franklin to step in for him.

[music]

Emil: Aretha Franklin, first of all, greatest voice of all time stepping in for Pavarotti at the last minute, and reading through this aria and phonetically memorizing it to come out and sing. For an Opera singer, period, that is a huge feat to perform that song and live, right? Then for her to be able to do that in not much time, and to really slay it, it really showed you how Black art transform genres.

Kai: Is it fair to talk about those kind of moments in the way I did, like as disruptions?

Emil: I think disruption is right because I think as much as we lead so much of culture, we still were not given full credit. That's why I was thinking about your previous question, about you can't really see that today, but you still can actually, because we are still left out of so many conversations and we're still kind of second class citizens in many ways.

We always as Black people have to disrupt things to make sure that we get credit for things, so of course, if Aretha Franklin's going to be given the opportunity to sing Opera at the Grammys, she's going to slay because that's what we do.

Kai: All of this history informed and inspired your professional choices, I gather. Talk about how you understood the work you and your colleagues set out to do when you created Vibe in 1993.

Emil: Vibe was definitely a very special moment in time. I always tell people it was my first great love because our mission, basically dictated by Quincy Jones, was how do we celebrate Black music and culture in a way that Rolling Stone have for rock and roll and the way that Vanity Fair had for Hollywood.

There was just a group of us that believed that these stories were really important, that these artists were larger than life, and we wanted to bring that to life in a time where hip hop is just really starting to build its foundation in a way that popular music is paying attention to it, but not really. It was this very, very profound moment in time of what does a magazine look like that celebrates hip hop, R&B, rap music, dance music, dancehall, reggae, dub music, what does that look like?

Then it was just all these people clamoring to be in the magazine, and on the covers because they weren't seen in mainstream publications and definitely not on the cover, unless they died. It was a huge opportunity.

Kai: Yes, unless they died, right.

Emil: Yes, unless they died.

Kai: What role do you think it played in the commercial world of music for these artists?

Emil: It was important for record labels specifically, who didn't have a lot of venues to place their artists. They would sell, but being on the cover of Vibe Magazine or being featured in Vibe Magazine was a really, really big deal because it was cosigning kind of from Quincy Jones and his legacy, that this is what's hot, this is what's next. The first issue was Treach from Naughty by Nature.

[music]

There's OPP, it was huge in the streets, in the hood, but after that it was huge on MTV.

[music]

The second cover is Snoop Dogg

[music]

That, people knew who he was in West Coast Music, but to then to be on the cover of Vibe Magazine with a full cover story, I think pretty much helped launch his career. We saw that happen over and over again.

Kai: We, of course, cannot talk about Vibe and its history in this moment without touching on its role in dispute between Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls. Biggie was ultimately killed outside of a Vibe after party for the Soul Train Awards in 1997. A variety of media have been blamed for inflaming the tensions between those artists and generally, the idea of beef in hip hop. I don't really want to litigate that dispute so much, I just wonder about how you think about Biggie's death in that moment and whether was it or was it not a marker of some sort in this history that we're talking about?

Emil: I think that Biggie's death was definitely a very dark marker and moment for Black culture, and Black history because arguably still, the best rapper of all time is struck down way early in his career. I think the fact that it was centered around gang-related violence, East Coast - West Coast and Black and Black crime, like Black folks beefing with other Black folks about who's the best, that's sad to me.

Biggie and Tupac separately, both brilliant young Black men who are also like a window to the future, they're shifting the way that we ingest music, that we think about our community, that we think about how we look as Black men, how we move through this world. Then because of a battle between both fractions, the two stars both get killed it's like Shakespearean, really.

Unfortunately, it was a really hard moment to be at Vibe at that time because as exciting as everything was happening with the music and the culture and the vibrance of it all, it was scary because you never knew if you were at a party, what would happen. There was just a lot of violence at that time, that is unfortunate because it spoke too, to white supremacy and how we can turn on each other. Like, get them to turn on each other, and that's what happened and it's really sad.

Kai: Tell me about your work on Native Son. Your work at Vibe was, at least in part, giving Black artists the celebration and attention that part of the commercial mainstream denied them. I do wonder about your experience of that as a Black gay man.

Emil: Sure. Native Son is a movement, community and platform, which was created to inspire and empower and celebrate Black gay and queer men. I was the first openly gay Black man to edit a national magazine. When we won the National Magazine Award for general excellence, it was a really big deal because here before, Black gay men were always regulated to the backdrop. We were the choreographer, the hairdresser, the stylists. We may have had some role, but it wasn't really given a lot of attention.

One of the things things that I did while I was editor-in-chief, was to ensure that we were covering HIV/AIDS, we were covering LGBTQ folks across the spectrum, at a time where that wasn't popular. I got a lot of heat for doing that coverage, but I felt like it was important as a Black gay man to bring those stories to the forefront, but also to overall, health and wellbeing of the Black community, we needed to have those conversations.

A lot of that is what led to where we are now with Native Son. I would have to say that also a big chunk of my time at Essence after Vibe, really inspired a lot of Native Son. I saw how Black women really lifted each other up in the way that Essence did.

Kai: Say more about that for a second. Unpack that a little bit about what you learned at Essence, that you thought this is an important idea for me to carry forward amongst Black queer men.

Emil: Sure. Essence Black women in Hollywood was like this huge lunch that they did during the Oscars to celebrate Black women in Hollywood, who were breaking through. I sat there like, "I want this from my community." I want to be in community with other Black gay and queer men and feel empowered and inspired. What does that look like? I remember being at this, it was like a women's empowerment luncheon that Lisa Nichols was hosting, and she talked about not pouring from your cup being empty, but from the overflow. All the things she talked about, I literally was like bawling in the audience.

I ran backstage to where she would come out and I was like, "I need to talk to you, because you just moved me in this way. I know I'm not the target audience at this event, but you spoke to me" [laughs] A lot of that, like how do we as a community lift each other up, how do we see each other, how do we celebrate each other, how do we show up for each other, really stuck with me and I started researching famous Black gay men. It was really hard to find pictures and it was really hard to find information.

The more I dug, the more I was like, there's a need to create a platform, a movement where we see each other, that we know from whence we came.

Kai: Emil, we first met in, gosh, I don't remember if it was late '90s or early 2000s, as part of an effort to organize Black gay men around the response to HIV, and raise consciousness amongst ourselves. I think about that moment in the context of Native Son and the work you're doing now, and I guess it just makes me want to think about the arc of Black gay male consciousness in the culture. From when we met to now, what does that make you think about?

Emil: It makes me think about creating safe spaces and I mean that's what Native Son really does because when we met, it was a safe space, where we talked about who we are in the world, but who we are as Black gay and queer folks in that particular space. I think that we don't have enough of those safe spaces in the world, and so Native Son is really creating that, where people can come out and say, "Hey, I'm HIV positive," or, "Hey, I may have drug addiction, or this and that, but I'm still okay. I'm still good because my community is going to support me in that."

I think what's definitely different from that moment in time when we met till now, is that that CDC report hadn't come out, that in our lifetime, one in two Black gay men who have sex with men will contract HIV.

Kai: 50%.

Emil: There's so much work that still needs to be done and a lot of it can only be done in safe spaces.

Kai: Where do you see yourself and the work that you have done and the work that you are doing in the continuum of our history?

Emil: I think you said it best earlier about disruption, and being disruptors. I feel like I'm disrupting culture and community and really presenting for a future generation, this is who you are, this is where you came from, and there's a whole community that looks like you, that are thriving, surviving, and shining bright. I never thought that I would see in my lifetime a Lil Nas X

Lil Nas X: Call me when you want, call me when you need, call me in the morning--

Emil: Let alone a Saucy Santana.

[music]

To have those artists exist in a world where they can be free and then on top of it, win Grammys and VMAs, is almost beyond my wildest imagination. If we can feed that, support that, and just build up this community of Black, gay and queer folks, so that they feel comfortable in the world and the world understands who they are and respects them for that, then Black History's been made.

Kai: Thank you so, so much for that role in history and for this time.

Emil: Now, thank you for having me. This is amazing.

[music]

Kai: Notes from America is a production of WNYC studios. Keep up with the show by following us wherever you get your podcasts and on Instagram @noteswithkai. You can always talk to us by going to our website @notesfromamerica.org, or you can just click on our little record button and leave us a voicemail right there. We'd love to hear from you.

Mixing and theme music by Jared Paul. Matthew Mirando is our live engineer. Reporting, producing, and editing by Karen Frillman, Vanessa Handy, Regina de Heer, Rahima Nasa, Kousha Navidar, and Lindsay Foster Thomas. Andre Robert Lee is our Executive Producer, and I am Kai Wright. Thanks for spending this time with us.

[music]

[00:26:42] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.