Black History Is Now: How Misty Copeland Went From Different to Special

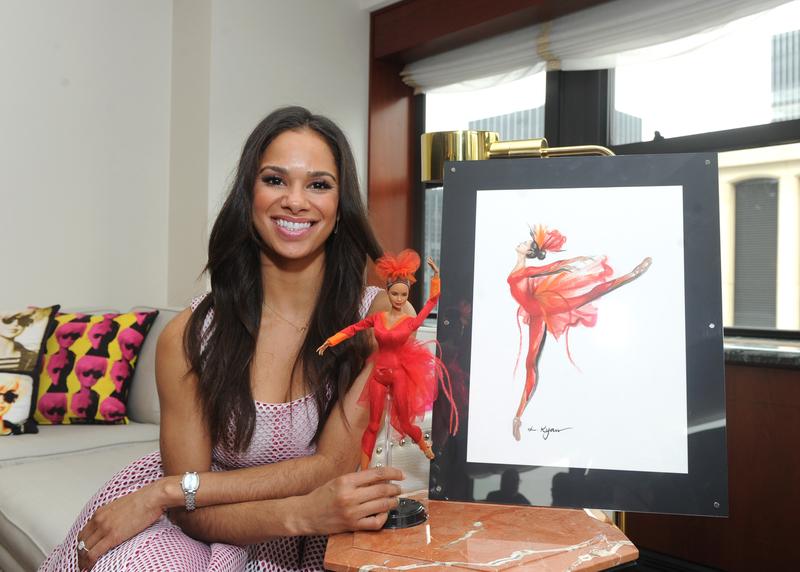

( Diane Bondareff/Invision for Barbie/AP Images )

Student 1: Misty Copeland is a person that every Black ballerina wanted to be, still wants to be at this point. She's the gold standard for the Black ballerina.

Student 2: Misty Copeland's story is one that I think all dancers, but more specifically dancers of color, can find inspiration from.

Student 1: She's a legacy in the dance world.

Student 3: She is a trailblazer to all of the little Black dancers who needed someone in their life to give them inspiration and dance. Whenever I dance, I feel like I can be myself, I can express myself. Whenever I'm dancing, I'm happy. I just love to dance.

Student 2: Dance to me means growth. I've been dancing since the age of three, and there's never too much you can learn. It's something that you can never really perfect, and it's something that you always work at. There's continual development and inspiration.

Student 3: Her legacy means to me it's like looking in a mirror and seeing myself there because when I talk to all of my friends and they have dancers that I look up to, it's mostly not people of color. When I think of Misty Copeland, a dancer of color, I just think that's me.

Student 1: I think seeing someone, who like me had a single mom, was able to get what they wanted and what they needed out of life without having to compromise who they were, that means the world to me. As it can be quoted in her book entitled Life in Motion, this is for the little brown girls.

Student 4: Exactly.

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright, and those young people are students at the Jones-Haywood Dance School in Washington, DC. It was founded in 1941 to educate Black youth in classical ballet. As you heard, Misty Copeland is a hero to those young ladies and to many others. In 2015, Copeland became the first African American woman ever to be a principal dancer at the American Ballet Theater. By that point, she was already a sensation well beyond the dance world.

Her performances drew these huge crowds of new young audiences to this classical forum. She'd even been in a Prince video. This week, we continue a series we're calling Black History Is Now by meeting Misty Copeland. She has thought a lot about the role she plays in the lives of young dancers like those students you heard, in part because she thinks so much about her own mentor. Last fall, she published a memoir called The Wind at My Back: Resilience, Grace and Other Gifts from My mentor, Raven Wilkinson.

Now, Raven Wilkinson, who died in 2018, she was a Black soloist in one of the most important ballet companies of the 20th century. Copeland writes about discovering Wilkinson as this other person who carried so many firsts and onlys and about the friendship they developed.

Misty Copeland: The first time I came across Raven, I was in my twenties, still pretty new to being a soloist at American Ballet Theater, and really just searching for this sense of identity as a ballerina and belonging in this very white world. I think I was injured at the time. I had sprained my ankle or something, and I was at home sulking on my couch and decided to turn PBS on and saw this documentary on the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Everything changed from there. I was seeing this Black woman come onto the screen for the first time, seeing this recognition. I'd seen other Black ballerinas.

I knew about Janet Collins and Virginia Johnson of course Dance Theater of Harlem but for a ballerina to exist in the time that she did with one of the most recognizable ballet companies of the 20th century. To see the passion and love and hope that she had when speaking about her experiences, even the negative experiences of her life being threatened by the KKK and the injustices that she had experienced in her life and within the ballet community, and yet she still had this undeniable love for the art form, and she was still such a champion for it, it just made me look at my life and career so differently.

Kai Wright: How did you meet?

Misty Copeland: I had actually just started working with my manager, Gilda Squire. She's a great listener. Raven would come up here and there whenever I would do interviews, and Gilda decided on her own to do some research and find out who this woman was and what her deal was, was she still alive, and found out she lived a block away from me on the Upper West Side.

Kai Wright: Really?

Misty Copeland: Yes. It's really unbelievable. I can't imagine how many times we probably passed each other on the street. Gilda suggested that we do a conversation at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and that was the very first time that I met her in person with the night of the panel discussion. We were inseparable ever since.

Kai Wright: I want to make sure people don't lose track of the unique nature of that meeting. You were the only Black ballerina at the American Ballet Theater for the first many years of your career. Then in 2015, you made history as the first Black woman to be a principal dancer at ABT. That's the first time in 75 years at ABT at that point. I guess I want to underline that connection and what it was like for you given all of those superlatives and singularity in your life to then come across this person from the '50s who was in a similarly singular moment.

Misty Copeland: I don't know that I fully grasped that at the moment that I saw her and heard her speaking, but that was such a strong connection and understanding of what it is to be alone and the only. It was the first over 10 years of my career that I was by myself in American Ballet Theater, and I needed to have a connection to someone who truly understood what that meant, the emotional and psychological weights that you carry with that experience. Raven was a soloist with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. To this day, it's rare to see a Black female soloist in a classical company.

She was the first and only. It's not common that a dancer makes it out of the corps de ballet which is the lowest rank. Typically, the structure of a company is the corps de ballet, the soloists, and then the principal dancers. The corps de ballet are the large group of dancers that create the atmosphere, surround the soloists in the center. Raven went through the corps de ballet in a couple of years and became a soloist and was doing principal roles as a Black woman. This story, I felt this sense of connection, of course, and that I belonged to a community I didn't know really, really existed but at the same time this frustration and anger, why don't I know this story?

Kai Wright: This story's erasure was so total that Misty says at the time she discovered Raven Wilkinson, there wasn't even a Wikipedia page about her.

Misty Copeland: I was working with dancers who worked with Raven in the company at American Ballet Theater, and it never came up. There was conversation around me being the only Black woman or only the second-ever female soloist of color in the company. It's mind-blowing to me that those stories weren't even shared with me. She was an afterthought and something that people didn't even truly think about what she did on the stage but what she was experiencing off the stage that most people would break in 30 seconds.

Kai Wright: What did she experience?

Misty Copeland: Raven would be in Alabama, somewhere in the south, and she'd get on the tour bus, and the tour bus would be stopped by the KKK. They'd run onto the bus and be searching for the Black person and threatening her life. They'd come onto the stage during a dress rehearsal. These are the things that she was going through before having to step into this space and be mentally and physically and emotionally prepared to perform and also perform for an audience of white people that didn't want her there.

It's unbelievable that she was able to perform the way she did. I wish that I would've thought to ask her these things while she was still alive. I've asked her friends and roommates what type of space was she in when she'd get to the theater, and they were like, "It was like nothing happened. She would get prepared."

Kai Wright: Just a pro.

Misty Copeland: They never talked about it. Just a pro, and go out there and do it. It's just mind-blowing to me. It was unbelievable the things that she witnessed and went through which eventually led her to leaving America and going to Holland where she performed the rest of her professional classical career away from America.

Kai Wright: As with many Black people of that generation-

Misty Copeland: Exactly.

Kai Wright: -got tired of it. Misty Copeland's own story is also remarkable, but before telling it, she cautions people not to indulge their stereotypes about Black athletes and the cliché up-from-poverty narratives. That was not Raven Wilkinson's story, for instance.

Misty Copeland: That's not the experience of every Black person in America. Maybe coming from--

Kai Wright: It's not all under this unless that.

Misty Copeland: Exactly. With that said, I grew up in a single-parent home. My mother raising six children and extracurricular activities, the arts, sports, whatever it was, that was the furthest thing from my mother's mind. It was keeping us off the street. It was keeping food on the table, a roof over our heads, which wasn't always the case. We were constantly moving. I'd say from the time I was born until the age of seven, we had moved, I don't know, 10 or more times and changed schools and sleeping in other people's homes that I didn't know.

We had lived in motels. There was just never this sense of comfort that I could relax, and music and dance became the solace for me. When I heard music, I wanted to move. It was this beautiful escape. I grew up watching BET and VH1 and MTV and seeing music videos. That was what I thought dance was. That was my idea of dance, so when ballet was introduced to me, I was like, "What is this?" I'd never heard classical music before. It was all very foreign, and I wasn't interested.

It took a lot of pushing and the teacher trying her best to articulate to me that I was a prodigy, that she'd never come across anyone that was as physically capable. My body was retaining the information. It could physically do these things. Also, mentally, I had an understanding and the way to connect the music to my body, and I ended up living with my ballet--

Kai Wright: Once that teacher did convince Misty she had something, a lot happened fast. Professional ballet dancers typically train from the time they are little kids, but for Misty, after just four years of training as a teenager, she moved to New York and joined American Ballet Theatre. Honestly, prodigy doesn't even describe that, and I was floored that she couldn't hear it when her teacher told her she was special.

Misty Copeland: If anything, I wanted to not be noticed. I wanted to hide. I had so much shame around my life and the way that I grew up. I didn't have a lot of friends because I didn't want them to know that we were scrounging for money in the couch cushions in order to buy food and that we didn't have a home. Just this thought of standing out or being special or unique in any way-- I was used to being different but not with this positive take on things. I don't think that I understood that until I was an adult.

I started to fall in love with ballet, and I really enjoyed the work. I enjoyed being in the studio. I enjoyed the repetition. I enjoyed this structure that I'd never experienced in my life, and I was craving. I held on to all of those things rather than you're naturally gifted. It was really difficult for me to embrace that I was good at something.

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America, we'll be right back.

[music]

Kai Wright: One of the reasons mentorship is such an important idea to Misty Copeland now is that she can actually point to a number of Black women who have helped her navigate this unexpected life as a superstar classical dancer with a Black body. One of them was actor Victoria Rowell. Now, she has done many things, but she is certainly most famous for her nearly 20 years starring on the daytime TV show, The Young and the Restless. Victoria showed up in Misty's life and just made a profound impact.

Misty Copeland: When I moved to New York City, I had no guidance. There was no one to-- I moved into an apartment. I didn't know how to grocery shop. I had never lived on my own. I'd never lived outside of the small town in California, like pay your bills, manage-- You're feeding, you're athletes, and I didn't know how to do any of this. I grew up eating a cup of noodle and Taco Bell. I had no idea all that it really took to perform at this level. It was around that time that the company was on tour in Hollywood.

I looked on the bulletin board where they post the casting and you sign into the theater, and there was a note, this tiny note with my name on it. I opened it up, and it was from Victoria. She just had said a little bit. She didn't say too much. She was like, "I've been watching you. I used to be a ballerina. I would love to have you over to my home and just talk like two Black ballerinas." I was like, "What?" I'd never been approached by anyone to be a support system, let alone someone who looked like me and had somewhat experienced a similar thing.

She had me over to her home that night, and we stayed up all night talking. The importance of having that support and understanding of what it is to be a Black person but a Black woman with Black skin and a Black body, embracing the body that I have, that it's going to look different from the girls around me, but there is a way to be healthy and take care of yourself and thinking of your body as an instrument, all of those things.

Kai Wright: How did she teach you that? What do you think?

Misty Copeland: It was having a realistic conversation. It's not about sugarcoating it and saying, "Look--" In my heart of hearts, I knew I was not eating the right things and I was not in the shape that I needed to be in. It's having those real conversations. There are certain expectations and things that you have to do to take care of yourself in order to get on stage and get through with a three-hour, four-act ballet, and be in shape and be healthy and take care of yourself. I think that I didn't really understand what that meant, and she was very direct about that.

I think having it come from her didn't feel like there were these underlying racial tones or whatever it was attached to that. It felt very straightforward. I had had a lot of those conversations with my artistic staff, and it just never felt like it was coming from a caring place. I felt there was a lot that was wrapped in the Blackness of my body, wrapped into the things they were saying and how they were saying it, and so I took it differently coming from her. It opened up how I felt I could have an impact on other people, and especially Black and brown dancers.

Kai Wright: As you have now become a mentor yourself, what kinds of things are you hearing from young people who aspire to be classical dancers? What do you hear in terms of their challenges and their inspirations?

Misty Copeland: It's changed so much. I feel like before it was like, "How do I even get my foot in the door and even have an opportunity to show what I can do?" Now, the conversation is like, "What do I do once I'm in the room?" It's a different time. Even after the last two, three years, a lot has shifted in the ballet world, and then you add social media on to it. A lot of it I'm like, "I don't even know what you're talking about. [laughs] I’m so far removed from" [laughs] It's so empowering to see young people want to make an impact and have a voice.

I think the difference is that, whereas before, a lot of Black and brown dancers were terrified to even step into that position of saying something, of sharing their experiences out of the fear of not even being given an opportunity because they'd be reprehended. Now it's like, "What platform do I use? How do I get my voice?" They want to be activists. They want to move the needle. It's a very different time, and it's fascinating to be in this position, and having seen so much growth and change within our community in the ballet world. I'm just proud that I have so many dancers that are doing the work that I've been fighting for and doing for my entire 25-year career.

Kai Wright: In those 25 years, you perform some iconic parts, but in the book, you describe this vivid moment with Raven Wilkinson that happened right after you danced Swan Lake at the Met, which you were the first Black woman to do that. Tell us about that moment and why it sticks with you.

Misty Copeland: [chuckles] This is probably one of the most memorable, not just in my mind, but in my body and in my emotions of my time with her. Raven talked about this want to perform at Lincoln Center as a classical ballerina. She never got the opportunity to. She had auditioned for the Metropolitan Opera ballet and was not accepted, which is unbelievable. In 2015, she was able to step onto the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House after my debut in Swan Lake as the lead, as Odette, Odile, and present me flowers. It was this outer body experience. She was actually passing the torch to me.

She was standing on the stage of the Met where she should have been able to dance. She undulated her arms like a swan and the audience just erupted into screams and applause. I just remember crying and falling to my knees and trying to pass the flowers back to her and she's passing them back to me. [laughs] It was one of the most special moments of just giving her her flowers.

Kai Wright: Quite literally.

Misty Copeland: Quite literally.

[applause]

[music]

Kai Wright: Notes from America is a production of WNYC Studios. You can follow us wherever you get your podcasts. By the way, later this week, we'll put a longer version of the conversation with Misty Copeland in our feed, so check it out. You can also follow us on Instagram @noteswithkai. Mixing in music by Jared Paul. Milton Ruiz is our live engineer. Our team also includes Karen Frillmann, Vanessa Handy, Regina de Heer, Rahima Nasa, Kousha Navidar, and Lindsay Foster Thomas. Andre Robert Lee is our executive producer, and I am Kai Wright. Thanks for spending this time with us.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.