The Birth of the Modern Campaign

( ASSOCIATED PRESS / AP Images )

BOB GARFIELD This is On the Media, I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And I'm Brooke Gladstone. There's hyperbole about the critical importance of every general election, but this time the claim is most definitely warranted. The results may determine what our nation stands for, for generations. But modern methods of seeding lies and hysteria into a campaign. The precision of it, the craft, can be traced back to a single race in 1934 for California governor. Some years back, we talked to two lifelong students of history about how that race was run and what it wrought. We began with Greg Mitchell, who's written a dozen books about U.S. politics and history of the 20th and 21st centuries. He said that the governor's race was intensely watched because it was seen as a judgment on FDR's New Deal because seemingly out of nowhere, the Democratic primary was won by Upton Sinclair, the prolific, muckraking author of The Jungle, which galvanized public outcry over the reckless disregard for public health and workers' lives in the meatpacking industry. An unabashed socialist, his political star rose when he launched a hugely popular anti-poverty campaign.

[CLIP]

UPTON SINCLAIR No excuse for poverty in a state as rich as California. We can produce so much food and we have to dump it into our bay. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE "I aimed at the public's heart," he wrote, "and by accident I hid it in the stomach." Mitchell told us that the reaction to Sinclair's primary win was swift and furious, ushering in the first modern media campaign. Mitchell described him as, among other things, a militant vegetarian, erstwhile socialist and scourge of the ruling class. Erstwhile, because after several unsuccessful runs as socialist, Sinclair changed his party affiliation to Democrat.

GREG MITCHELL He led a mass movement called End Poverty in California, or EPIC, and managed to sweep the Democratic primary in a landslide with hundreds of thousands of votes and was the favorite to win in November.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So people knew who they were voting for?

GREG MITCHELL Oh, absolutely. He was one of the most famous authors in the world. Today we remember him mainly for the jungle. But at the time he was always in and out of the headlines getting arrested and was certainly a famous figure in California and around the country.

BROOKE GLADSTONE As you describe it, the swiftest response to his winning the primary came from newspaper magnates like William Randolph Hearst and the Chandlers. All right. The family behind the Los Angeles Times and also Hollywood.

GREG MITCHELL Well, of course, the newspapers at that time were extremely reactionary throughout the state. They are owned by families. They had a lot of money at stake, and, you know, Sinclair, bless his heart, had been one of the leading media critics of his day. We think of Sinclair today as this muckraker, like an investigative journalist or something. It was mainly a novelist. And even The Jungle is a novel, so what the newspapers would do is they would take some outrageous thing that a character in one of Sinclair's novels said and pretend that Sinclair had said it himself, so they would put it right on the front page and have him believing in free love and giving away money to everyone and hating the church. So, yeah, the newspapers were in that were in the forefront of the fight.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The Los Angeles Times also took shots at Sinclair's followers.

GREG MITCHELL Yeah, they called him the maggot-like horde, then. It was so over the top.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The political editor of the Los Angeles Times was a real kingmaker. His name was Kyle Palmer, and you cite this really amazing anecdote when he's having a conversation with The New York Times' star reporter who is in California, a guy named Turner Catledge.

GREG MITCHELL Turner came out there to cover the campaign and in a fairly even handed way and was amazed there was no coverage about Sinclair at all in the L.A. Times, except for all the negative shots. And so he asked Kyle Palmer, how can you get away with only covering one campaign? And Palmer said: "Turner, forget it. We don't go in for that kind of crap that you have back in New York of being obliged to print both sides. We're going to beat this son of a bitch, Sinclair, any way we can. We're going to kill him.".

BROOKE GLADSTONE Quote, unquote. OK. So what was Hollywood's beef with Upton Sinclair?

GREG MITCHELL They thought that Sinclair and his former socialistic background was a threat to the movie industry itself. And so the first thing they did was they threatened to move to Florida. When that didn't work, they docked each of their employees one day's pay to be donated, then to the GOP candidate. And then finally, Irving Thalberg at MGM. Made these newsreels that presented Sinclair and his supporters in the worst possible light. And we're actually mainly faked footage. Some of it was shot on the studio lot. They hired actors to portray bums and other other Sinclair supporters.

BROOKE GLADSTONE This was the famous humanitarian Irving Thalberg?

GREG MITCHELL He admitted it after the campaign that he was the one and I managed to find these newsreels, they were sort of missing to history. They were really the first attack ads on the screen. And people back then got a lot of their news off the newsreels and they thought they were the straight deal.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You say that this campaign marked the beginning of media politics. I wanted to make that argument for me because certainly negative advertising did not begin with the gubernatorial campaign of Upton Sinclair.

GREG MITCHELL There, of course, had been dirty campaigns before this, but campaigns had always been run by political parties and their local leaders. But the Sinclair threat was so great, they turned the campaign over for the first time to what we now call political consultants. To PR people we now call spin doctors. The first turning over the campaign to advertising people. The use of radio and the screen to make attack ads and national fundraising from all over the country. In one state race, all of those things were unprecedented.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What was the substance of these smears that made it so unprecedented?

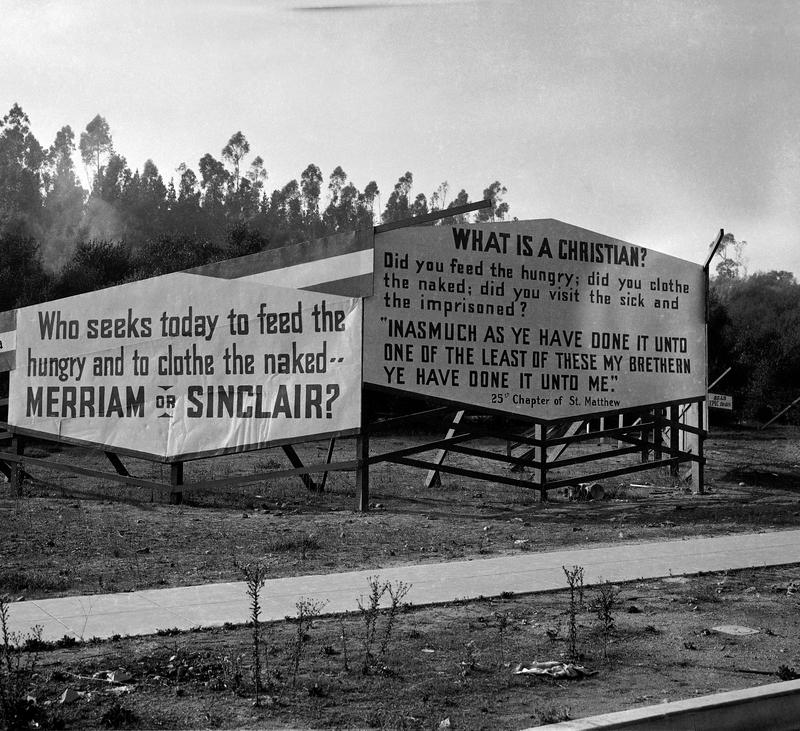

GREG MITCHELL The Sinclair said that if he was elected, California would become such a paradise that the unemployed would want to come to California. And of course, he was just joking about it. But they took that and they made radio dramas around it. They made two of these fake newsreels around it. They plastered it on billboards all over the state.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Horrific images of huddled masses crowding in to California.

[CLIP]

NEWSREEL Your inquiring cameramen interviewed, 30 stated that they were on their way to California to spend the winter and to remain there permanently if the EPIC plan went into effect. [END CLIP]

GREG MITCHELL Hearst owned movie theaters, so he worked with MGM to get these newsreels into his movie theaters. He had all these people on every level of radio, newspapers, movies, advertising, all in the same room and saying, OK, how can we direct this campaign using all these different tools?

BROOKE GLADSTONE You're describing a sort of vertical integration of the political smear.

GREG MITCHELL That's right. One of the things that was continually used against Sinclair was that he was a free love advocate, almost what you might call hippie bohemian and so forth. This was because there were characters in his books who had these traits. He was a vegetarian, you know, which at that time was seen as somehow un-American. So he had some personal traits. But the odd thing was he was such a straight laced. Not in any way a free spirit that they pictured him as.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So are you convinced that it was the negative advertising that took down Upton Sinclair?

GREG MITCHELL I think after coming off his primary win, which is at the very end of August, the EPIC campaign was an incredible mass movement. I mean, they had 800 chapters around the state. They had a weekly newspaper that had two million circulation. I would say that if these new techniques and over-the-top, incredible dirty tricks had not been employed, that Sinclair would have narrowly won.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Greg Mitchell is the author of, among many other books, The Campaign of the Century: Upton Sinclair's Race for Governor of California and The Birth of a Media Politics.

BOB GARFIELD Hollywood may have bankrolled and assembled the anti Sinclair ads, but who helped to shape them, to coordinate them? Who holds the techniques of the out of context quotation? And opposition research, now part of the standard campaign playbook.

JILL LEPORE Sinclair writes a book about what's been done to him, and he calls it the Lie Factory. But he doesn't even really know who's done it, who's behind it.

BOB GARFIELD The masterminds behind that campaign were Clem Whitaker and Leone Baxter, the owners of Campaigns Inc, the world's first political consulting firm.

JILL LEPORE They use invented organizations to print pamphlets all the time.

BOB GARFIELD Jill Lepore, New Yorker staff writer, Harvard history professor and author of Just About Everything You Need to Make Sense of American History. We spoke to her about eight years ago after she profiled the duo in The New Yorker.

JILL LEPORE Clem Whitaker had been a longtime newspaper reporter. He also founded a wire service, The California Feature Service. And Leone Baxter, who's this young widow, is hired to work with him on his first political campaign. They fall in love. He divorces his first wife and marries her. They worked behind the scenes, no one really pays much attention to who they are, so it's very different from political consultants today who very much adore the limelight and are very much celebrities.

BOB GARFIELD And yet, semi-anonymous as they were, they dominated this fledgling industry, winning 70 out of 75 campaigns. What was their secret sauce?

JILL LEPORE Well, the first thing they do is they hibernate for a weekend or some number of days when they're hired by any campaign. And they come up with a plan of campaign. They come up with all the rhetoric that they're going to use, exactly the way they're going to position their candidate. Then they write an opposition plan of campaign to imagine that there was someone actually opposing them, but there is no opposition. There are no other political consulting firms before the 1950s, so they're just really fighting their own shadow. They're boxing in the dark. But Whitaker says there's only two ways to interest Mr. or Mrs. America in a political campaign. You'd have to put on a fight or you have to put on a show. It's no coincidence that political consulting comes out of California. It's very much bound up with Hollywood. Whitaker and Baxter had a rule. You know, if you have to explain something, you've already lost the issue. That you never explain. Your obligation is to simplify the message and go on the attack. You can't win a defensive campaign.

BOB GARFIELD One of the tricks was to come up with an allegation and just repeat it endlessly, no matter how dubious its merits.

JILL LEPORE Among the rules was this - you have to say something seven times to make a sale.

BOB GARFIELD It also has echoes of Goebbels, the dynamics of the big lie. Were they on the same track?

JILL LEPORE You know, it's something that people in the 1930s are very concerned about with radio in general. There's a lot of concern in the 30s about propaganda in Europe. There's obviously a lot of concern about the border between fact and fiction in American radio broadcasting. They just think about War of the Worlds and the controversy that that sparks. Baxter in particular later in life. Looking back at the work she had done, thought about, was there a difference in what she was doing in Nazi propaganda? Not obviously the level of content she thought what she was doing was principled and that her political arguments were sincere. And I think they indeed were sincere. But I think she had come to understand and this is reflected in this quite powerful oral history interview that's conducted with her later in her life. You know, it's like sort of believing in a benevolent dictatorship. You can't accept that these tools are a good thing if it depends on the nobility of the intentions of the people who hold them.

BOB GARFIELD What's so spooky about your New Yorker piece is how much it seems to presage what goes on today. Tell me about the campaign against government mandated health insurance.

JILL LEPORE Whitaker and Baxter were first hired in the state of California to defeat Earl Warren's proposed statewide health insurance program in the 40s. They had actually gotten Warren elected governor, but he had then fired them. He was pretty concerned about the methods that they used. He proposed a health insurance program. They were hired, Whitaker and Baxter were hired by the California Medical Association to defeat it. They used all of their classical methods. They decided that what Warren was proposing was creeping socialism. They invoked the specter of Stalinism. They defeated it successfully by one vote. Warren was outraged. Harry Truman then picked up the cause both in California and nationwide. Compulsory health insurance was incredibly popular. What Whitaker and Baxter did when they were hired then subsequently by the American Medical Association was take those same techniques that they'd use to defeat health insurance in California and bring them to the nation at large. And they did so very much with an eye toward defeating not only that proposal that Truman had offered, but health insurance forever afterwards. They tell the AMA, you are hiring us not just to defeat this piece of legislation. You are hiring us to put an end forever to the idea that the federal government could have anything to do with health care.

BOB GARFIELD This whole conversation, Jill, is premised on the idea that Campaigns Inc created in the thirties the template for all modern political campaigning. It's also completely protected by the thing we hold most dear, the First Amendment. Are we doomed to this kind of political cancer forever?

JILL LEPORE There was a great moment in the 50s when this political scientist named Stanley Kelly went around and interviewed a bunch of political consultants who were just starting out. He's even wrote this book about the founding of this industry. He said, you know, "what's gonna happen?", "What's going to happen with this stuff?" and one guy says to him, "I give it a few months 'cause really we're sellin' so much baloney. How much longer could anybody possibly believe a word we're telling them?".

[BOB LAUGHING]

JILL LEPORE [LAUGING] You know?

BOB GARFIELD Jill Lepore is the author of many books about American history, most recently. If Then: How The Simulmatics Corporation Invented the Future. Coming up, the whole press corps sitting with Linus in the pumpkin patch.

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.