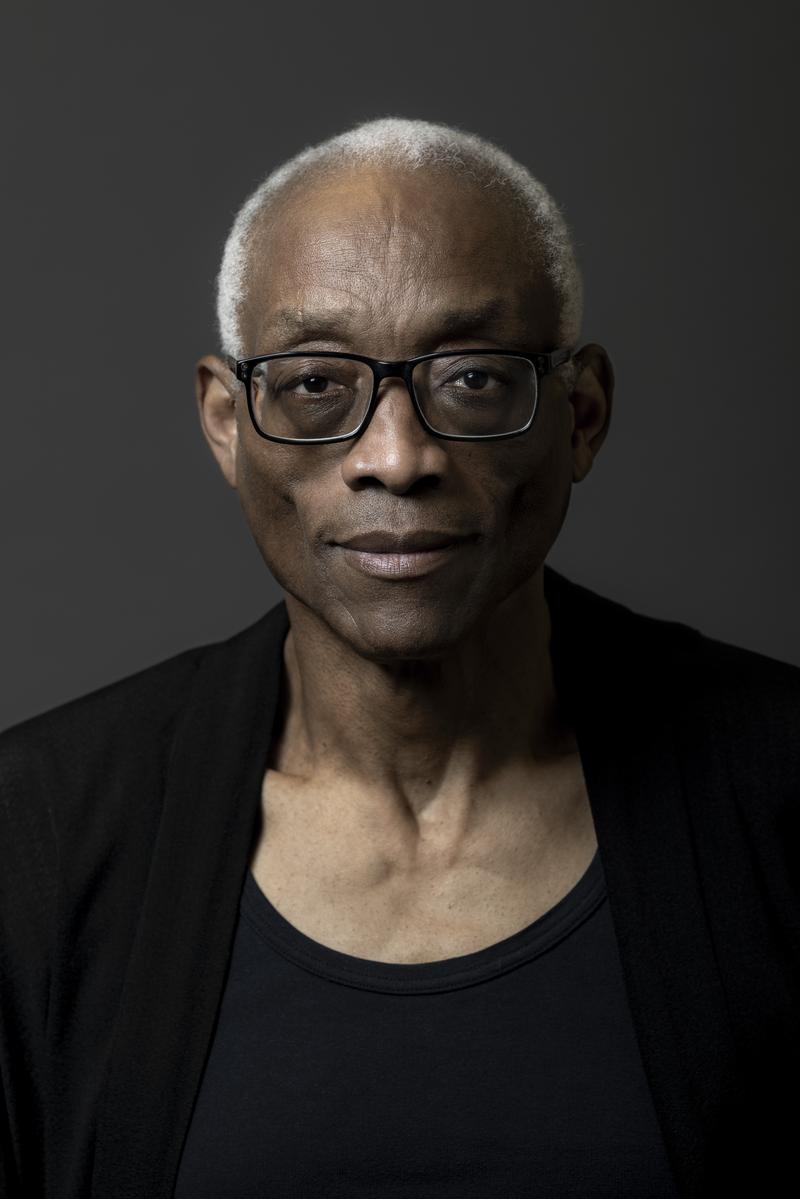

Choreographer Bill T. Jones on the violence within seduction

( Maria Baranova, courtesy of New York Live Arts )

Bill T. Jones: [00:00:00] And I know that when I was a young stud, young buck out there doing my thing, I knew that there was a power I had when I stripped off my shirt and when I would look you in the eye as I moved my hips. But I also knew the other side of that attraction to me was the impulse to kill me.

Helga: What does seduction really mean when the seduced has all the power? What character must one summon when the seducer fears for their own life? I'm Helga Davis and welcome to my show of conversations with extraordinary people. In this conversation I explore with legendary choreographer, Bill T Jones, what it meant for him as a young dancer to take his shirt off and engage an audience he was [00:01:00] told to fear and engage them with brutal, unapologetic honesty. He also talks about why after Alvin Ailey, there are so few black choreographers. And how after decades as a performing artist, the body may retire, but the mind never will.

How is it that you came to dance as a young person?

Bill T. Jones: That is, um, a question every time I hear it, I get a little weak in the knees because I think I'm going to another opportunity to lie. Um, seldom consciously lying, but there's something about the wages of time on the memory. Um, as when I, I have to back way up to say that I am, uh, uh, the 10th of 12 children in an African American family.

Um, we were [00:02:00] field workers. My dad decided in 1955 to stop migrating up and down the Eastern seaboard, harvesting fruits and vegetables. He decided instead to become a black Yankee. And there are many people these days who don't understand what we mean by Yankee, nevermind a black Yankee. I was fortunate, uh, unlike my brothers and sisters who would be in six school systems a year, sometimes even more, I was able to go K through 12 in the same German Italian dominated school in the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York. It was there that I did sports. It was there that a love of reading came about. It was there that I experienced from a safe vantage point everything that was happening in civil rights and social change, and it was there that I began to do theater.

Helga: I'm gonna stop you a second because what I feel is that this is a thing that is [00:03:00] quite well rehearsed by you. It's a thing that you have said, it's your story, it's your narrative, and you know all of that. But I'm thinking about you being born into this family. Knowing that you are, you are a young, black, gay man that you—

Bill T. Jones: None of those things meant anything at that time.

None of those things meant anything. That's language of our era.

Helga: How is it that it didn't mean anything at that time, Bill? It's the fifties!

Bill T. Jones: We have to go back to where I was, not where we are now, because I don't think we even had the notion of “gay.” I was trying to find a way. To actually be all the, the various things that I acknowledge now.

I was trying to understand what it meant to be um, the child of Estella and Gus. They did not read. I read. I understood number 10 out [00:04:00] of 12 kids, what is my identity in such a tribe? I was trying to understand what taste was, why I like certain things and my brothers and sisters liked other things. I was trying to understand my mother and my father as men and women prototypes cause that supposedly was my future. I was going to find a wife and I was going to quote my mother said, take care of some woman's daughter. And my father says, earn a living. I was trying, if you're talking 10 years old, that's the, that's the things I was doing.

I was also doing, uh, athletics. I was trying to please my brother Azel, who was a good athlete and I wanted to, he wanted me to go to the Olympics. I was in a German Italian community and I was trying to understand what my mother meant when she said white folks, and those were my classmates. What was this thing that she understood that I didn't, or I understood that she didn't?

All of that was going on.

Helga: What is interesting to me and important to me is that you had that experience and it felt to me that everything you did after that was about continuing to be all of the things that you are, to have the freedom to express yourself creatively, to do, to find your voice, and then, ultimately to encourage others to do the same, and this is why I'm interested in this part of your life.

Bill T. Jones: I think when you're that young, you are—every day is a delicious, terrifying thing. And it had to do with understanding how to deal with what was going on inside of me. And what I was trying to project outside.

That's why I say it's very difficult to answer this question without getting on the psychologist or the psychiatrist couch. Uh, because I [00:06:00] was just a kid doing things that kids do and one of those things that kids do is try to please the adults, surround them. And it was a complicated group of adults with Estella and Gus. Two black people who had, for economic reasons became Black Yankees. And there are people like my first-grade teacher, Mrs. Zimmerman, uh, who, uh, who, who loved me and gave me particular attention that I didn't know what she was, why she squeezed my, uh, arm the way she did when she put in an orange in it at Christmas.

What was there about people who, who—he bus driver, Mr. Woods and his wife, these old white people who invited me out of all the kids in my house to come over and have ice cream at their house and my mother actually allowed me to do it. And what was there about it that they wanted to take care of me. Um, I was [00:07:00] trying to play to a very complicated audience, and at the same time I was really loving life. Loving the feeling of the body and loving this sense of the jukebox and loving food my mother's cooking and loving the notion of the future that what was going to come. So that's, that's, uh, that's the truth. Now, the truth is, is malleable. Um, if you want to push me in a certain direction, I, I don't know.

I didn't know who I was going to become. I didn't know. Performing was a way of trying on identities. That's not an original thing to say, but that's how I felt.

Helga: And when did you start to dance? When did you begin to dance?

Bill T. Jones: When I was 19 at the State University of New York at Binghamton. Not in my small town. I was doing theater there.

I took dance because dance was, I was in an, I was a runner. I was doing athletics [00:08:00] practice. My niece Marion Young, my older sister's daughter, who is my age, said to me one day at SUNY Binghamton, Bill, don't go to those, um, to track practice, come to these dance classes. They're really kicking. You're gonna love it.

And sure enough, I went there and I fell in love with the sweat in the studio. And um, they had a very big charismatic teacher whose name was Percival Borde, Trinidadian married to the legendary Pearl Primus. He was a great accident actually. I had never seen a black man, uh, do art dancing. I had seen Sammy Davis Jr. tapping. I had seen Bojangles with, with Shirley Temple in the old films I'd, I knew of, uh, the brilliant, uh, Sydney Poitier, but I had never seen a “dancer of artistic dancing” until Percival Borde and he was doing [00:09:00] Afro-Caribbean dance. I began to take modern dance with a woman whose name was Linda Grandy, who had been in the company of Charles Weideman and, uh, Doris Humphrey, and she was teaching me the classical modern style. And I was one of maybe two men in the class primarily of women.

So that was at the university.

Helga: And then after you were in the university, were you, were you auditioning for companies or did you know pretty much, uh, soon after that you needed to make your own?

Bill T. Jones: At the university, I was there. I met Arnie Zane. I can't tell the story of my development as an artist without telling my private story as well.

Arnie Zane was the one that encouraged me to go to [00:10:00] Amsterdam. And in Amsterdam I began to take classes there, rudimentary jazz taught by a platinum blonde Dutchman, and it was done for tall, uh, Dutch women who were secretaries. This was not what I thought it was going to be. Around that time because of things that were happening in America, I realized that I was being inauthentic and I came back to America to find my true self and part of that true self was to become committed to becoming a professional dancer. And now we're talking probably 1970, 71. I, Arnie Zane and I, our relationship was such that we went and did everything together.

He was a photographer and he was interested in dance because I was interested in dance. We met a woman whose name was Lois Welk. She was, uh, one of the founders of the [00:11:00] American Dance Asylum, which was a countercultural idea of a group of people living communally and making work together. Yes we would each get to direct the others.

Um, maybe, maybe for two months I might be making a piece for the other four members and then we would switch it around. We were teaching each other as well and doing yoga, those things in a small, in a converted, um, girls club on the north side of Binghamton.

Helga: And were you all living together as well?

Bill T. Jones: Yes, we were, we were, we were, we were like a hippie commune. We were counterculture people and we were hardly, um, recognized by the cultural persons in that town. But it was only because, well, we rarely went to New York. We thought that New York was a place that you lost your soul in because we, like I say, were kind of back to [00:12:00] the earth, uh um, authentic counterculture people.

And I went down one weekend with a group of people from the Dance Asylum and I saw an advertisement for auditions at the Clark Center Dance Festival, which was happening at that time—Clark Center was a place that Alvin Ailey did early, uh, rehearsals with his company. Maybe people like Rod Rogers also, and were also working there.

But, um, we were these kind of snobbish, um, new dance people. We didn't know what we were, were, were, but we knew we were not that. And I went to this audition, uh, as a kind of a defiant lark. I didn't think they would think I was very good and they wouldn't take me, and I was trying to do work that was too complicated during an audition. It had multimedia, which meant a slide projector with slides. It would be plugged in. It had lighting effects. And how do you do this in a [00:13:00] rehearsal? I mean, I'm sorry, in an audition. I did it. I made certain gestures. During the audition, I called out spontaneously to somebody, “Hey, soul sister, turn of the lights.”

I did, I broke all the rules. I should have been quaking in my boots in front of this, uh, group of people who were all incidentally sitting in the dark. They were sitting back, so I couldn't tell who was black, who was white. They were sitting there to judge, and that is just what it was like a bowl with a red, uh, piece of cloth waved and I went for it.

I was belligerent. I was going to be in your face. I was, didn't, none of this mattered to me anyways, and I left and I got a few days later, back in Bingington, I got a call from a feisty Jewish woman whose name was Louise Roberts. Um, uh, she left us many years ago, and, uh, she said that the panel was interested in what you did, but there were certain things that you did and said that they wanted to be assured that you would [00:14:00] not do again.

And I said, what are you trying to censor my work? And she said, uh, Buster. She said, Buster, you've got a chip on your shoulder and New York is going to knock it off. Do you want this or not? I hemmed and hawed for a second. I said, yes, I want it. Yeah. And I came to dance there near Bryant Park in Midtown, not to park from the public library.

They set up chairs every summer there and they would do, uh, showcases. It was only a matter of time before we would have to leave Binghamton and Arnie and I were ready. He was a New Yorker and he was by my side, so I felt I could do anything. And we came to New York.

Helga: And Bill, did you feel when you saw all of these other dancers and the, the people who were making work as you were doing this audition and having this person say to you that New York is gonna knock the chip off your shoulder, did [00:15:00] you nonetheless feel that you belonged here?

Bill T. Jones: I had never understood belonging to anything except as Estella Jones and Gus Jones.I didn't, you gotta realize we were black people. My dad leaves the black community and comes up north to become a black Yankee in a German Italian community. My parents never went to the pancake breakfast at the high school.

My mother was very, uh, uh, very, uh, correct about our shots and she would, uh, interact with the principal of the school. She was very alert to her kids being treated in any way that was untoward. But I did not feel a part of anything except my family. Now that with, as a teenager, you know, that is, that's a battleground. What about the world? I can remember the very day I was, uh, coming home from basketball practice in that late winter, and I was walking by a pool of [00:16:00] half frozen snow and a car came by, splashed covered me with that, uh, mush. And at that moment I said, oh my God, there was a time before I was alive and there will be a time after I'm no longer here.

I remember stopping in the street and having a guest, the zen would call it a satori moment, and I was 14. And then you began to realize that there is a huge world that you may or may not be a part of. Um, so I mean at that, it's a bit colorful way to describe it, but no, this idea of belonging, I struggle with it even now. Belonging.

Helga: Can you say in what way you struggle with it now? Or, or why, what are the events that cause you to struggle with it?

Bill T. Jones: Well what does it feel like not to belong?

Helga: No, I'm asking you what the interactions are or yeah—maybe first the interactions that cause you to feel that you don't belong?

Bill T. Jones: Well, uh, I would like to first just say there's a feeling of fear and loneliness that comes on one in the middle of the night, uh, that when you're a child it has to do with, um, witches and demons and, and, uh, what's under the bed. Something else happens when you become a, uh, young, sexual being in a world that you don't understand.

Why was it yesterday I was playing with these kids, but that today, this particular person who happens to be a little girl, now there is a barrier between us. What happened? Of course, I had heard my parents talk about Jim Crow and racism and horrible things, but somehow their experience was in a book somewhere. It was not my experience. And then I began to realize, oh, this is the complexity of the world. [00:18:00] Um, when people, uh, would say things like, um, at like Mrs. McLaughlin and if her son ever hears this, ‘cause he and I have been in contact, cause I mentioned her many times in different, she was very important, probably the most cultivated woman at Wayland Central School. Very sensible, very serious musician. And she wanted to coach me to become for oral competition, a singing contest, a singing, uh, competition that happened, uh, yearly in my county. And then you went on to the States. But so, uh, I remember working on aria, um, which was an art song. All these terminologies were new. And she said to me, your diction is not good. Your people, if they want to be equal, they must be equal and always, if not better. Now, this is what this, this white lady is saying to me, and I don't think she meant it in any way, but how did [00:19:00] it land? I heard all sorts of things bubble up. My mother's, uh, irateness about white people thinking they’re better than black people. Uh, I heard the fear that, um, my parents had. We would not get the proper education because education's gonna help you have a house and a car and you're gonna get, uh, respect that we never got. I heard all of those things. There was the athletics. Athletics you expected to, because you were black, you expected to excel in.

I had, did not have a hand eye coordination for basketball like my brother Azel did. I could excel at running. I did not know that there were people around who found me amusing, but I did not know what they found amusing about me. I was just trying to get over. So, um, in a, in a school primarily of young white kids, [00:20:00] pretty conservative kids, they, um, didn't really understand when they, when you were much younger, washing your hands at the sink and they said, oh, it, we thought it would come off. We thought the dark color would come off when you washed your hands. I knew that was absurd. I didn't think they were serious, but what can I do? I had to take it. So there was a a, a lot of things that I had already been prepared for by my mother that white people don't really want you and they will kill you if they get a chance. That I understood why people want you to work for very little money. They don't want to live next to you, but they do want you to work for them. My mother never encouraged me to clean houses or be a waiter or anything. She said I'd done enough of that stuff. So there was something, some legacy that we were living through and past that, uh, had been sprinkled since first moments of [00:21:00] my consciousness, but now it was different because I was developing as a sexual being and as a aesthetic driven and thinking human being. Um, and I can, to this day, I realize that I must have known even in high school that I was not destined to be a member of this community, even though at that time it was fine, but I am not interested in going to high school reunions, uh, and the people were not bad people except that I just don't think, I like going back and returning who I had been when we were all much younger.

Helga: You’re listening to Helga, we'll rejoin the conversation in just a moment. Thanks for being here.

Bill T. Jones: The Brown Arts Institute at Brown University is a new university wide research enterprise and catalyst for the arts at Brown that creates new work and supports, amplifies and adds [00:22:00] new dimensions to the creative practices of Brown's arts departments, faculty, students, and surrounding communities. Visit arts.brown.edu to learn more about our upcoming programming and to sign up for our mailing list.

Helga: And now let's rejoin my conversation with dancer and choreographer, Bill T. Jones.

I'm curious also now when you hear conversations about people of color reclaiming themselves and reclaiming the lens through which they view their experiences, their work, their desires, their hopes, and that they want to move away from a white gaze. Does any of that mean anything to you right now [00:23:00] or, or affect how you work and think?

Bill T. Jones: Well, it's complicated. In the sense that I have been in love with, uh, three people, all of whom were men, and two of them were white men. The middle one, Arthur Aviles, was a white Puerto Rican. So already for me to be talking in about black and white, it was, um, love, eros, uh, attraction in some way uh, transcends all of that, particularly when you're young.

Yes. I was aware through James Baldwin. I was aware through my mother's stories and my mother's anger that I was coming from a place where my experience was alien. I had gone K through 12, kindergarten through 12th grade with the same [00:24:00] German Italian kids. My first kiss was probably with a white girl.

I'm not sure about that. I'm not sure. But it was, uh, no. All of this, this consciousness, uh, had to become mine only after years of being a professional artist in an interracial relationship, being deeply in love with a man who was very exotic. He was a New York Jewish man, and he had his own scars and, and pains that as any two people in love, you share.

And he taught me about loving myself in a way that nobody else could, I think. Yes, he was, uh, he, he knew how to love my body without fetishizing it. And I realized how fortunate I was, that that was the first person I fell in love with. So, um, the black and white dichotomy and all, which I am [00:25:00] very much dealing with, right now, trying to understand as I am 70 years old, I have a body of work behind me. I have a multiracial, multiethnic company. Um, I have, um, and I'm trying to understand why I make a new work and what level of emotional involvement is involved in the making of that work. How, where am I digging now for the truth of my life.

Race is important, but even since George Floyd, race has moved back into proportionality to my other questions about what is the meaning of life, what is beauty, what is mark making? What lasts? What is form? Um, but race with George Floyd in particular, and COVID I felt I almost went insane with it.

Helga: Why?

Bill T. Jones: I was so angry. I was so, um, I felt so betrayed by everything I've told you about my dad being a black Yankee, my mother expecting me to speak proper with the white people. But when you come home, be real, what do you, what do you mean you sing that to a five, six year old? What does that mean? They didn't know how to explain it.

And nevermind sexuality. The fact is that my first fantasies were, um, well there were, there were, there were girls, but the, the, the ones that were most troubling were the ones I was having about my teammates on the track team, on the, on the ball courts. And these were white guys. So your question is a very complicated one.

And yes, black people, now black artists are asking the question about being themselves. And our trans, uh, brothers and sisters and others make it very clear child, you do you. Well, okay. Bill T. you do you, you're a [00:27:00] you-centric. You love the work of Proust. Merce Cunningham was very important to your development. George Balanchine is an example of art making. You love to think about what cubism took from Africa, but you're also wondering about the mystery of how form is found that transcends, uh, gender transcends, race, transcends, uh, national identity. What is this thing called poetry? All of these are the things that beset me right now and I use my biography as a kind of, um, radioactive material to go into because I don't think where I came from is not where I want to end. And you know what? I don't know where I want to end.

Helga: Hmm. It's hard for me to think of you as retired. I think I forget that.

Bill T. Jones: [00:28:00] Well, are you, the body retires as a performer, but you certainly as an artist, you don't, I don't retire. I'm, um, madly, uh, studying philosophy on my own right now. Every day when I'm on the machine working in cardiovascular, I watch documentaries.

I do not watch drama. I just finished, um, uh, big questions or philosophy. I am a member of the Hannah Arendt, uh, virtual reading group. It meets every Friday, and we're reading through her work throughout for the last couple of years. I am constantly trying to “cultivate my mind.” So, no, I have not retired from that, which I think is a big part of art making.

But no, the idea of being the body on the center of the stage, which is what made, uh, Deep Blue Sea singular because I quote, came out of physical retirement in order to do that piece and had to confront what I could and could not do. Uh, because [00:29:00] just the body, I know you're a performer as well, but the body of a dancer sometimes your body, your, your identity is when you were maybe 25, 26, 27 years old.

And I'm 70 years old now, so I have to, when I get out into that zone, which is the performance field, I expect that I could run, stop, turn, lift, roll, like I did 40 years ago. And, um, that just ain't true. And it doesn't have to be true. There's so much richness to be discovered in, uh, in the mind and in loving, just what does it mean to have a long term relationship, uh, when you no longer have to seduce the world? Which is what I felt like as a young man. Um, and now I don't have to. Then what are, what is your body for. And what happened to your sexual desire? What [00:30:00] happened to your, your, um, well, sex and spirituality? Yeah. What, what's all, what's going on there? And now that you realize the body, there's more years behind than ahead, what was this all about? What is it all about? Those are questions I wrestle with now and I take very seriously the fact that, um, the dance, movement based, we don't say dance, we say movement based investigation, is a young person's game. Max Roach said to me, he was a real friend. He said, man, you know, just when you, uh, start to understand your instrument, then you can't even do it anymore.

And I thought that was a, it was quizzical when he said that to me back, I don't know, back at the, the early eighties. Uh, and I, now I get it, Max. Now I get it. But I don't want that to, I don't, I don't wanna feel deprived. I'm trying to follow the evolution [00:31:00] of this thing, which we call a human life. And one of the beautiful things about COVID was staying in my house and our house in, we live in a suburban community.

We have, um, we live in a park-like setting with a house that Arnie and I moved into the house when he died into, but we have renovated it and I was able to sit for a year, two years, couldn't go anywhere, and just look at my garden, which is like a giant clock. There were term times during COVID where we would say to each other, did you see that flower? I've never seen that before. And one would remind the other, well, usually we're on tour. That's why you haven't seen it before, right? Cause you have not had, you haven't sat still in one place and really watched life unfurl. Now I'm trying to understand the whole of this life in that way. The springtime, the early summer, the mid-summer, the late summer, the fall, the late [00:32:00] fall, the winter.

Uh, I'm, I know it sounds like so much—it's, it's predictable, but you know, nature has, its, uh, it looks out for us. If you're paying attention, there are things to learn.

Helga: Bill in the lobby of New York Live Arts, there's a poster and it says, question violence, oppose violence, reject violence, reject violence.

Can you talk a little bit about what that poster is and how, how you are responding to this um, to these, to these issues?

Bill T. Jones: Well, it's interesting you should say that because I'm embarrassed to say, but I inherited that. Our merger, um, Billie Jones Arnie Zane Dance Company and the historic dance to the [00:33:00] workshop happened, um, over 10 years ago. The gala that you so wonderfully, um, MCed e was our 10 years at New York Live Arts and the 40 years of the company.

So those posters were there since another regime before we came, but it speaks so eloquently to the ethos of the place that we have kept it there. Violence, are you asking about violence?

Helga: I'm asking you to respond to the fact that this is, this is something that's in the lobby of your house and feels like a kind of, uh, charge if you will. What does that mean?

Bill T. Jones: Yes, but because things are there—because things are there staring at you every day, you don't really see them. I'm living what those, I'm living the impulse that made that poster. Um, it is in the art world that I come from, [00:34:00] many of the major practitioners are women. Women have a particular relationship to violence.

My leftist therapist, her name was Freda Rosen. She was a gay woman who, uh, was one of the first persons that really got me to think about this counterculture personality and what was lacking in it. She said that, um, uh, having your company is not about building something which is ego fulfilling, but you're actually building a social tool.

And she said, um, progressive men follow progressive women. Now that was a big one. And she said things like, women know that when men get angry, women and children get hurt. Now, I grew up in a house full of angry people. My mother was extremely angry, extremely violent. I [00:35:00] just assumed that was part of the funk that made blackness. People will slap you upside your head. You better shut your mouth. You're gonna get your ass kicked. All of that was what I took to be the love kiss from my culture. So it's, yeah, I did, I thought that that's what made for the funk. That's what made us what we are. That's where the blues comes from. That's what soul is. That's what—so your, your question is, it's, uh, so much about you is so surprising, but nobody has ever asked me about those posters before. And I thank you for that. But I'd say that this art form, this body based art form has been built by women, and women know something about violence. They also know something about the body and what it means to be looked at as opposed to do the looking.

There's violence in being looked at, and I know that when I was a young, [00:36:00] young stud, young buck out there doing my thing. And um, when I was a young, young dancer, I knew that there was something that they, a power I had when I stripped off my shirt and when I would look you in the eye as I moved my hips. I knew now, was that violent? Was that threatening violence? Was that seduction? But I also knew the other side of that attraction to me was the impulse to kill me. I knew my mother's tears in her eyes. She said, you can do anything you want. You a man, but don't go to jail because if you go to jail, I can't help you. And she would shake her head. I didn't know. What do you mean don't go to jail now? Now I know. Violence. Exclusion.

Helga: But Bill, is there a violence in the fact that you took off your shirt, that you moved your hips [00:37:00] in that way against you? Or did you, or do you perceive this as not just power, but also a kind of freedom?

Bill T. Jones: I think primarily it is not violent. I was offering what I thought I had and I was offering it inappropriately to the very people that I was told to be suspicious of, cuz they will kill you. Now, call it what you will. Is that really is, was that the ultimate freedom to look at your oppressor? To look at the person and, and seduce them and to uh, say I have something that I know you want, even though you don't know, you know you want it?

Um, I don't know. So that's a good you, it's very fair what you just did with that. Yeah. When I was, when I take my shirt off, I do not mean to aggress you, but I mean just the opposite of you. I mean, to get you to your breath to [00:38:00] change and that you meet you in some deep precincts of self. Why am I looking at this guy do this? Now you realize I'm not doing this anymore. I'm retired. So you're talking about me when I was dancing around the time that Last Night on Earth was written in 1994 when Arnie and I did our first works in New York, you know? You know, it was time, time changes those things. They change those things. Yeah. Now I have to work through that thing, which is called my company. There that's been quite a lift to be a black director. I mean, it's no accident that there's so few Alvin Aileys that have been produced in this country. Why have there been a lot of choreographers—why do we only have one Alvin? And there was something about being able to have the wherewithal to raise the money, to find the support for your ideas as opposed to your body.

[00:39:00] And that was a big one. And that's a painful one. Um, because if you enter into the bargain of, uh, trading on your body, why are you surprised that they don't value your mind? So those things have been, um, they, they, they, they bedevil me. But I think I'm winning. I think I'm winning. My work is taught in schools. I meet so many people who remember the first time they saw it or their parents took them to see it. You know, I, I feel it's, uh, I feel I'm okay. I'm okay. I'm, I'm actually ready to move on when I have to move on, or, that's a mouthful to say in this conversation. Are you ready? Are you ready for what comes next?

Helga: I am indeed.

Bill T. Jones: All right. My sister, I'm glad to hear that.

Helga: There are lots of questions I would love to ask you, but there's also something else that [00:40:00] we are here to allow to happen and I would love for that to happen as well.

Bill T. Jones: Right. I am reading from a memoir, which I called a performance and text written in 1994, and because you wrote a quite beautiful homage, if you will, of uh, Deep Blue Sea, a work that I did at the Armory, and you caught me in a moment of deep commitment to my own performance. I wanted to go back to a time when I was performing consistently, and I'll read it. It's from Last Night on Earth. It says, “A performer secretly believes there's nothing worth doing other than performing. The entire day of a performance is nothing more than preparation for that 1, 2, 2 and one half hours standing in a glorious [00:41:00] arena, a circle of transformation, a ridiculous one ring circus, a black void with artificial sunrise, sunsets, tiny vortices of light, screaming shafts of illumination, striking the performer from this side, that side, a world wherein he's completely exposed, relying on minute tricks to hide imperfections and mistakes. The performer who takes a stage must believe that he is fascinating, that he or she deserves being the locust of several hundred or thousand points of attention. The job of the performer is to pull that instant community of individuals full of distraction, expectation, and hope into a timeless dimensional now. At best, he or she is a conduit, a vessel through which numerous substances are channeled, sometimes choking, sometimes abrasive or acidic, gouging, sometimes [00:42:00] sweet, surprising, and sometimes nothing. The performer feels small triumphs every time the last curtain call is taken and the sweat, like so many familiar salty kisses, pours down the temple, the bridge of the nose, skirts the eye sockets and seeps into the mouth. The nostrils know the smell of other bodies tired, demoralized, or ecstatic. The hands know the dusty weight of stage vollure, the feet filthy carpets that they shuffle across to and from a human environment of shower and dressing room. The performer knows waiting. The waiting for well wishers, friends, sponsors, waiting with anticipation when one feels good about the evening, dreading a look of disappointment or an avoided glance when the evening did not go well. I envy those who have [00:43:00] no desire to perform. Those who are content with breakfast, lunch, dinner, a good night's sleep, a vacation, a good book, a good fight, children, spring, summer, fall. Those who are content with being one of many. The performer wants to be one of many, but even more he or she wants to command the attention of many. Poor performer. He or she will never be satisfied. Perhaps dissatisfaction drives the performer. Perhaps dissatisfaction can itself be satisfaction, and then it's called wisdom. I hope so.”

That's from Last Night on Earth. A memoir or I said a performance in text that I wrote in 1994. Um, at that time I was waiting, I suppose, to die. [00:44:00] Arnie Zane had died in 1988 and I felt that every year that I had, after that I was stealing and therefore, I thought I would get, even with my chroniclers, the critics, what have you, who were writing about what I was or what I meant. I said, why don't I write my own? And that's what this memoir, this performance and text was Last Night on Earth

Helga: And to take control of your narrative as the folks say right now—one of the things that I try to give the people who listen to this work is an idea of simple every person practices that they can do to, as you say, get to the truth of who they are and who they wanna be, and are there [00:45:00] things that you do every single day that just a regular person could do towards that end?

Bill T. Jones: Yeah. Yeah. I, I, I'll start with the mundane. I have got to find, I tend to be a depressive person, you know, so if I'm not careful when I first go, I enter in the liminal state between sleeping and awakeness. Um, sadness comes over me and, and sometimes anger or whatever.

That's just almost habitual now. I think it's almost chemical now. I had to learn how to breath and, uh, my day, five days a week, uh, I exercise for cardiovascular. That's very important. But I do Qigong. I go outside no matter what the weather is, and I just do energy work. Now that's pretty exotic, I know. I was gonna take it a little higher and say every day I have the privilege and I hope your listeners have the privilege of turning over and there's somebody who I can say good morning [00:46:00] to, and they can look at and smile. That is I, you know, the existential question: born alone and die alone. I feel like I'm getting away with a big one right there. I am not alone. This person is my mate. This person wants to be there. I hope that everyone listening to this can exercise that.

Helga: That was my conversation with Bill T. Jones. I'm Helga Davis. Join me next week for my conversation with photographer and visual artist Carrie Mae Weems.

Carrie Mae Weems: I thought that she nailed it. Um, beyond all of the philosophers, beyond my pastor, beyond, um, the priest. It was my mother and her own deep thinking about the role of compassion in a life and how you offer that and extend that to others, that you extend [00:47:00] the empathy of humanity to all around you, regardless of who they are and regardless of what they think about you, is the act of grace.