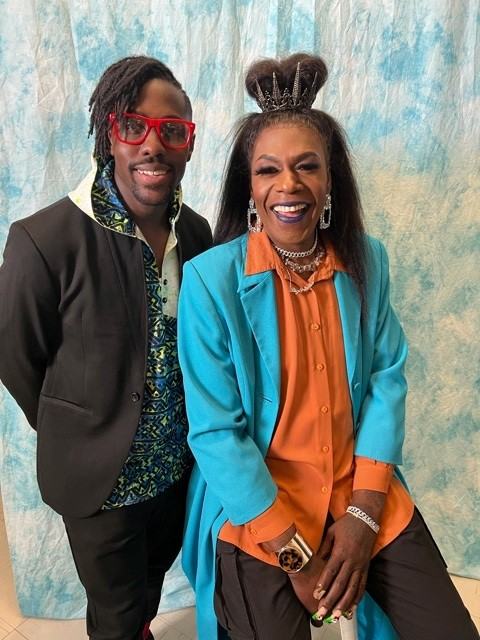

Big Freedia and Jonathan Lykes on Bringing Joy and Movement to Activism

( Courtesy of the artists )

Speaker 1: You and me at a bounce show.

Melissa Harris-Perry: It's The Takeaway. I'm Melissa Harris-Perry, and Mardi Gras season is in full swing y'all, so it's time for another installment of Black. Queer. Rising. I must admit, I am hyped to share this conversation with y'all because this one has bounce. The Queen of Bounce, Big Freedia, the New Orleans-based artists and icon. Freedia has been making crowds twerk it, work it, and shake it for decades, all to the percussive column response beat of New Orleans bounce music.

Now, if you're not from the 504, you might not have been familiar with bounce music until recently, but once Freedia teamed up to get Beyonce in Formation and ask Drake, Nice For What? She sparked a mainstream bounce craze, so much so that my eight-year-old daughter first encountered Freedia's music while dancing in our living room to the on-demand game, Just Dance.

[music]

Yes, my husband does cringe just a little bit every time Anna announces that this is her favorite Christmas song, but Anna, she's a Freedia fan for life.

Anna: What's it like to ride on a Mardi Gras flow?

Big Freedia: Mardi Gras Flow it is so much fun. The energy from the people coming down the street, and everybody screaming and hollering your name, and, "Happy Mardi Gras," it's an amazing experience. I suggest that everybody try it one day.

Melissa Harris-Perry: This year, as part of Black History Month, Freedia teamed up with artist and activist, Jonathan Lykes for the compilation album, The Black Joy Experience Volume 2: Comrade. Their mission is to educate folks about civil rights icon, Ella Baker, who was co-founder of SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Baker was among the most effective community organizers of the long movement for civil rights.

[music]

Oh, yes. I spoke with Freddia and Jonathan about mixing art and activism. Freedia started off by telling me about, and I hope this doesn't get me in trouble, so maybe earmuffs, kids. Bringing people together through the power of ass.

Big Freedia: Just all different walks of life coming together. That's what a Freedia show is and an experience. We learn how to party together and have a great time. That's what you get when you come to a Freedia show. That's the experience that I want to leave people with. Fortunately, it is through the power of ass. I bring all those asses together and it goes down.

Melissa Harris-Perry: For those who don't know bounce, and definitely we will bounce this segment, but for folks who don't know bounce, there's maybe some NPR listeners and public radio listeners don't know, tell us a little bit, what is bounce?

Big Freedia: Well, when I describe bounce music, I describe it as uptempo, heavy bass, column response type music, where it has a lot to do with dancing and body movement. It's embracing who you are on the dance floor. It was an underground thing from New Orleans for a very long time. I started to travel around the world and make people aware of the culture and its music. Now it has become infectious to everyone all around the world, everybody's bouncing now, everybody wants to twerk, everybody wants to shake, wiggle, and wobble.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Tell me about Katey Red.

Big Freedia: I started with Katey Red, helping Katey to background, going to the studio and to travel different places locally here in New Orleans to perform. Katey was the first trans to come out with bounce music here in New Orleans. Me and her were friends before that. When she stepped into the bounce music scene, I was right there to support her. Maybe a year and a half to two years later, I jumped in the game and I've been rolling ever since.

Melissa Harris-Perry: It always strikes me as maybe it's particular to New Orleans, but maybe it's not, that bounce music, which is the music of the city, it's, maybe outside of jazz, the most identifiable cultural piece operating in pop culture in the city now for a couple of decades. You, Katey Red, other trans, and queer artists, are also right at the center of that culture, but there isn't in the sense that, "Oh, if I'm a cis straight brother from the 7th Ward, I can't be associated with bounce music because it's queer." It's all part of the piece of the thing that is bounce.

Big Freedia: Yes, most definitely. There were lots of artists before we jumped in the game, before the queers started to step into the scene. Tons of people, DJ Jimmy, DJ Jubille, Miss T, Cheeky Blakk, Mia X, Soulja Slim, Lil Wayne, Juvenile, all of them were into the bounce scene before we even stepped in. It is definitely a cultural thing that all of the artists here locally either did or do. You can't live in New Orleans and not be a part of the bounce scene.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Jonathan, I want to bring you in here. We're hearing some here from Freedia about the music and about the collaborations. What did Freedia's music mean to you before the two of you collaborated?

Jonathan Lykes: I move through joy, and through happiness, that is my thing. Nothing encompasses the power of Black joy, the power of joy as an act of resistance, the power of centering joy as a practice in our lives as bounce music, and as Big Freedia's both presence moving around the earth. I also think it's essential to highlight the importance of Black, queer and trans people centering our identities in our art. I was just so excited to work with Freedia. Not only is she just a downright professional and talented, but she's kind. If we can't be anything else on this earth to the people around us, we have to show love and kindness to each other.

Not only kind to me, kind to everyone she comes in contact with. It has really been an absolute joy.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Now, Jonathan, talk to me a bit about, I hear you and I both hear and I feel the joy as you talk about moving through joy and this opportunity to connect. What is this collaboration, which I got to tell you, I clicked on Ella Baker Shaker and I haven't really stopped. I have been for this at every moment, but tell me about this collaboration?

Jonathan Lykes: Absolutely. First, the history of just the Ella Baker Shaker is rooted in an organization I was a part of cofounding, Black Youth Project 100. It was back in 2013, when Dr. Cohen brought us all together, where it was--

Melissa Harris-Perry: Y'all listening, check that fully. That is professor Dr. Cathy Cohen, who is an absolute giant. She's actually very tiny, but she's also a giant in the field, was a mentor of mine, and helped to make the BYP100 a possibility. We got to get the full citation for Cathy Cohen here.

Jonathan Lykes: Dr. Cohen was my professor, my thesis advisor, and I still connect with her often today. Yes, it was through BYP100, where it was first yelled out in the room, "Where are the Ella Baker Shakers? Please come up to the front." In the tradition of bounce, it was a full twerk session. That's the history of just the concept of the Ella Baker Shaker. It was always moments of joy inside of movement and community building as we're fighting within the movement for Black lives.

I was lucky to get connected with Freedia's team through another nonprofit called the Marigold Project. We were able to record the song back in September in Atlanta, and the collaboration has grown from there.

Melissa Harris-Perry: I want to back up for a second for folks who might not know this history and then, Freedia, to bring you into this a bit as well. When you talk about BYP100 being founded in 2013, what I remember distinctly about BYP100 is that you were all together having your first big national gathering that Professor Cathy Cohen had brought you all together for as the verdict for George Zimmerman being found not guilty for the murder of Trayvon Martin was handed down.

I guess as I'm sitting here, thinking about the grief, the determination that you all must have been feeling in that moment. It's part of how the organization was founded. Yet also that there was space within, maybe not that night, but within the work that you all were doing to have the Ella Baker Shaker call out. Jonathan, first tell me a little bit about that moment, and then, Freedia, I'm going to come to you on this.

Jonathan Lykes: Yes, that moment still sticks in my mind. The day that, I call it a kairos moment of stars aligning. Who would have thought that was a generational shifting moment, that is our Emmett Till moment of my generation. Many people can remember where they were when we knew for sure, again, in this new generation, that Black life is not valued. I happened to be standing in a room with 100 other Black activists and organizers on that 2013 July day, and it was tragic. It was really tragic.

We stood in a circle, and we had the verdict playing live. I can just remember, a lot of crying, a lot of screams. We literally debriefed that moment for the next several hours, where we immediately went into organizing and planning of what can we do next? How do we respond to this moment? Ultimately, BYP100 and many other organizations were birthed out of that moment.

Big Freedia: For me, this experience was another sad thing for our community. We were thinking that justice would be served. Like Jonathan said, it was the moment where we saw that Black life did not have any value, and I was just very sad, I was upset. I wanted to speak out and lash out at different people. The way that we handled that, I just went into prayer. I went into heavy prayer of just trying to keep my mind stable, and also just praying for the people out there, especially for the Black community, that this will not turn to a more violent situation than it already is, or turn in to a situation that will get out of hand and have to bring in the National Guard, and so forth.

I just was praying, that's my go-to. The two Ps is my formula all the time. I pray and I push. That's where I was when this situation happened. My heart went out to the families and friends of Trayvon Martin hinges. The whole situation was very sad and unfortunate that it happened. Just was praying for a better outcome, but unfortunately, that didn't happen. Just taking it one day at a time, how can we change this? How can we fix these situations? How can we not go back into the old times where we were dealing with all of the same things back when Dr. King was living?

Melissa Harris-Perry: Freedia, then five years later, you did lose your brother to gun violence, which is something so many of us with loved ones in New Orleans live with and deal with. What do you think we're getting wrong when we have our public conversation about gun violence?

Big Freedia: First and foremost, I think that the conversation needs to happen a lot more. A lot of topics that they are touching on are not really the base of the situations. I've done a documentary just recently on gun violence and about how we can try to help change some of the gun violence and some certain things that's going on in the world. I think these conversations need to keep happening with our leaders though. I think that's the main thing that needs to happen. It needs to happen more on a national level from all of the people that's in control to run our country.

That's the big key here of opening the conversation to bigger people that's in bigger positions to help spear these conversations and see what we can do on a national level, not just locally, but national as well, of how can we start to put laws in effect to help change some of these gun laws.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Now, Jonathan, tell me, what role does joy have in that story? We have a story here about history. We have a story about work to do change. We have a story about the need for public policy. Tell me where joy and art and creation and creativity intersect with this activism work that you're up to.

Jonathan Lykes: For me, it's critical that joy be centered in all of our work. Just piggyback off the conversation of gun violence, when we see the over militarization of our communities of Black and brown communities. When we see guns being passed out like candy all around the country and compare that to several other countries, compare that to Switzerland, compare that to London where many of their police force don't even carry guns around. Where just the conversation around guns is completely different.

When we talk about centering life, when we talk about centering Black life, that becomes critical to this conversation and critical to the importance, the juxtaposition of that, which is conjuring up joy and love and peace throughout our lives.

The last thing I will say is, I do think it is very, very important that we use creatives, that we are able to utilize the creatives of this world, as the people who are world-making, as the individuals that will be able to tap into the radical imaginings and the radical dreams of our ancestors and bring a new world about.

Freedia said, we need to really start having these national conversations with more leaders, but at some point, we just need to replace these leaders. In the creation of this new Black Joy Experience album, we brought together 100 different artists and activists from around the country, representing eight different movement organizations. This is really a moment to create a new world.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Remind us one more time, Jonathan, who is Ella Baker, and how is she connected to that kind of creativity?

Jonathan Lykes: Absolutely. The story of Ella Baker is a brilliant one, I will call her Miss Baker for this conversation. She was a Black hero of the civil rights movement who inspired and guided emerging leaders. We build on her legacy by trying to build Black and brown power. She played a key role in some of the most influential organizations of the time, including NAACP, she worked with MLK at Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

She helped create most prominently for my life, she helped create SNCC, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and many of the people that Miss Baker mentored at SNCC, people like Courtland Cox, or Judy Richardson, have been a part of my life and have mentored me, and were there when we were creating the mission and vision, and value statements of Black Youth Project 100.

There's a lineage of the Black radical tradition that Miss Baker stands in the center of. If folks do not know her legacy, please go listen to the song, learn you something about Miss Baker, because it is the legacy and the ancestral lineage that Miss Baker walks in that we're standing in today, and that's giving us life, joy, and freedom that we're able to have today.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Freedia, here's my last question for you. This conversation that we're having today is part of a series that we're doing called Black. Queer. Rising. When you hear me say, Black, Queer, Rising, what does that mean to you?

Big Freedia: It means all of us coming together and living in our truth. Also, using our voice and our power to help us all rise up. It takes each one of us every step of the moment, to keep doing something, to keep changing something for the culture. To keep on putting ourselves out there, and not being afraid to just step off the edge and to do something that will help bring change into the world.

For me, every day when I rise and wake up, I ask God for strength to help keep on getting me through to the next day and to help what's my purpose in this world, and to help try to make change. That's what it's about for me, bringing us all together, helping us all rise up together. When I do what I do in this bounce music, I go out there and I just give my all, every step of the way, I give my all and I think is helping all of us rise.

Me being a young Black queer coming from Josephine and from New Orleans, and people seeing the growth of where I came from and to where I am currently now, I think it helps all of us rise. As well as me looking at other queer artists who have come from the struggle and to see them rise, I think that gives us all inspiration and influence to know that we all can get up there and rise and do something towards making change into this world.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Jonathan, when I say the words, Black, Queer, Rising, what does that mean to you?

Jonathan Lykes: Absolutely. When I think about rising, I go to Maya Angelo, and still I rise. Does my sassiness upset you? As a black queer, millennial in this world, I think so much about the invisibility of our lineage of queer history. I think that, many people still don't know to this day that the March on Washington in 1963 was organized by a Black queer person by arrested.

When I think of queer people rising, I think of the history of invisibility becoming visible. The history of those stories, those narratives. We are now in the roaring 20s where 100 years after the roaring 20s and the inception of the Harlem Renaissance. If you know that history, you know it was a very queer history that we are now 100 years past.

I also think of, I'm a member of the house in ballroom community. I'm in the house of Garson, so I think of the origins of the house in ballroom community, a queer and trans subculture that was created by Black trans women. When I think of black queer rising, I think of that 100-year legacy of house in ballroom culture and the Harlem drag balls that were taking place in the 1920s.

Ultimately, when I think of queer people rising, I think of, us standing in our dignity, standing in our full selves and recreating this world, not just for some people, but a world that works for everyone.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Big Freedia is a culture creator, a world maker and an Ella Baker Shaker, and also the queen of bounce music. Jonathan Lykes is an artist, activist and founder of Liberation House. Thank you both so much.

Jonathan Lykes: Thank you. We appreciate it.

Big Freedia: Appreciate you so much.

[00:22:02] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.