The ‘Big Bang’ in Jazz History

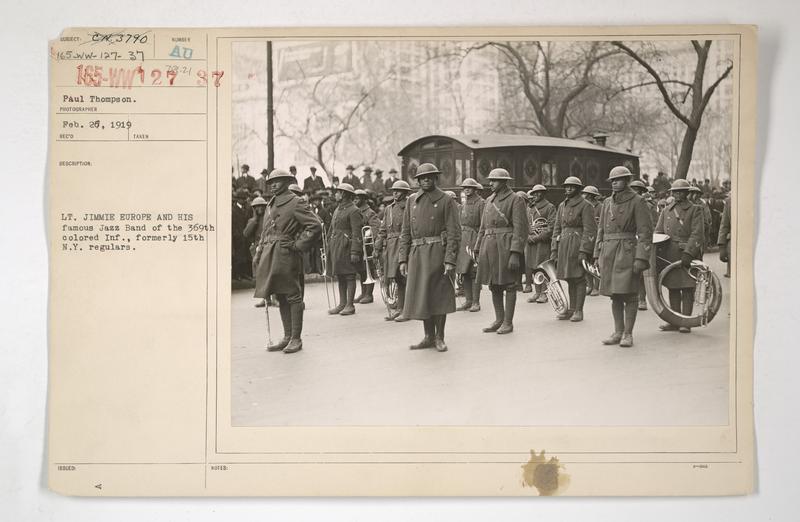

( Paul Thompson / National Archives and Records Administration )

[music]

Kai Wright: This is the United States of Anxiety, a show about the unfinished business of our history and its grip on our future.

Bill Williams: Every fallen family's feeling is the same, is that their loved ones are going to be forgotten, so that's our mission, is that they not be.

Carol Bachofner: The sacrifices our ancestors made, they who marched away, not for a moment, not for a day, away, away forever.

President Biden: I will give my all to you. May God bless America and may God protect our troops.

[planes flying over]

BBC Reporter: World War I brought about significant social change, not least, the introduction of jazz to Europe.

Narrator as James Reese Europe: “We won France by playing music which was ours and not a pale imitation of others.”

Roland Martin: The real patriotism is when you're Black in America and you fought for a nation even though that nation did not fight for you. That's real patriotism.

[music ends]

Kai: Welcome to the show. I'm Kai Wright, and happy Memorial Day, everybody. Since it's Memorial Day weekend, we're going to spend this show in a remembrance of our own. We're going to look back at World War I and a remarkable group of soldiers who made history on several fronts in the war itself, and the story of Black people in America, and in the history of American music.

To set the stage for that, we've invited one of our colleagues at WNYC, who gave us this idea in the first place and who helped produce the show you're about to hear. Joe Young is not just a proud servant of public radio, he's also a proud member of the US Army reserves, and specifically, he's an executive officer in the army band, so he's got a unique ear for this particular story we're going to tell. Hey, Joe.

Joe Young: Hey. How you doing?

Kai: Can we start with just sort of like this is a day that's been set aside for us to remember to commemorate those we've lost? For yourself, what are you reflecting on and remembering on a day like today?

Joe: Memorial Day is always built as remembering those who sacrificed their lives to give us freedom. What does that really mean? You can comprehend that they gave their life, and that in and of itself is sad, but I have to think of it in the tiniest details, things that you can actually feel. Like, what does it feel like to have known someone close to you all your life? You know all their little quirks, their personality, their smell, their tastes, their interests, and then that person is gone? You know what it feels like to hold their hand, to touch the shoulders, to lay next to them, and then they're gone.

All those really fine details of what it means to lose somebody is what I try and think of on Memorial Day. Yes, it's important to broadly recognize that these people gave their lives to fight for the freedom we have in this country.

Kai: In service in the military.

Joe: In service of our country, absolutely, but for me, until I boil it down, that's when the empathy just hits me at my core.

Kai: A lot more people can relate to that right now, I imagine, this Memorial Day, after the year we've just had, and all of the people we've lost to COVID as well, so that's a beautiful thought. What made you enlist, Joe?

Joe: Oh, I didn't know how I was going to pay for college, and I think that's true for a lot of people. A lady walked in to my band class in high school, in uniform, with a clarinet, and she said, "Play music, we'll pay for school." That was it. I was like, "Great. On it."

Kai: It's all you needed to know.

Joe: Yes, there was no sense of duty or patriotism attached to my enlisting, it was strictly pay you for school.

Kai: Tell us about patriotism for you and particularly the role of music in that patriotism.

Joe: When I started playing Taps, when I started rendering Taps for fallen soldiers, and to see and to hear the reaction from the friends and family members, sometimes it's just an outpouring of tears or sometimes it's absolute silence, hearing the silence is incredibly powerful. I've played Taps for veterans who have lived a long life and just passed away from natural causes and served their country with honor and their families that are grieving.

I've also played Taps for soldiers who have been killed in war, who have suffered from PTSD and taken their own lives, and to be right there next to the families and friends of these fallen soldiers, oh, it hits you like a ton of bricks, and that really forms what patriotism is to me. It's not just root for America, it's like root for each other. Music being able to pull those feelings out of people, it's-- I don't want to call it the best medicine, but it kind of is. It's so powerful.

Kai: You're describing these really wonderful and emotional experiences of being able to play this song for people in their time of need. How do you end up being that person? Are you on call to come to play at the gravesite or how does this work?

Joe: There are military buglers that are more or less on-call, that is their full-time role. That's not true of every bugler, but essentially, every bugler is always at the ready to leave and render Taps where it's needed.

Kai: I even love the way that's put, render Taps. It's not play a song, it's render Taps.

Joe: A thing that I find really special and interesting about Taps is all bugle calls, they have a specific dictated way to play them, a certain tempo, certain notations, but what is an unwritten rule among military buglers, is Taps this one where you can be a little free with how you express it, a bit rubato, because it's not something to be executed, it's something to be expressed and shared with the family and friends of the fallen soldier.

Kai: Can you give us some of that medicine now? Can I hear you play a version of Taps for us?

Joe: Yes, absolutely.

[Joe rendering Taps]

Kai: Thank you for that, Joe. That was really beautiful. Let's talk about that song. Where did that come from? It's probably the most well-known piece of music to come out of the military.

Joe: Yes. Initially, the military had drums and fifes, that sound like small piccolos that told soldiers how to move. Then the bugle came along and added to that role. It was a function. The bugle was there to tell soldiers where to move, when to go to sleep, when to wake up, when to put the fire out. One of the bugle calls, when it was just a tool, was called extinguish the lights, and it was taken from a French military bugle call. Literally, it was, "Hey soldiers, put the fire out, let's go to sleep, get your rest."

Kai: This is revolutionary war era or civil war era?

Joe: This is the civil war era and some commander along the way said, "You know what? I don't like this bugle call too much. I'd like to change it." He brought his bugler over, he hummed a tune to him and the bugler brought it to life, realized the tune, and said, "Great, I like that better. Let's use that as the new "put the fire out' tune," if you will. Not long after, there was a union captain, John Tibble, and there was a soldier who passed away and they were giving him a military funeral. Normally, at the time, they would fire volleys, the rifles, loud gunshots.

In this case, he didn't want to do that because they didn't want to give their position away to the enemy. He said, get the bugler and have him play Taps, and that's how Taps became associated with honoring fallen soldiers.

[music]

Kai: Joe told us that Taps was the first time that music in the military transitioned from being a tool, as he put it, those drums and fifes helping direct troops, to serving an emotional purpose, to being art. As we talked about it, I talked about my own fascination with the World War I era army band. It was a jazz band from Harlem, from New York's 15th National Guard unit, which is all Black. When that unit mobilized for war, they formed a band, one that made history. Anyway, Joe said that if I'm into that story, I had to meet one of his favorite jazz artists today. A guy who is so into that band's history, he's written the whole music programs about it.

After the break, I sit down at the piano with the world-renowned composer and MacArthur genius Jason Moran to talk about the musical history of the most decorated fighting unit in World War I. Stay with us.

[music]

Kai: Welcome back. This is The United States of Anxiety. I'm Kai Wright. It's Memorial Day weekend and we are celebrating with a remembrance of one remarkable group of soldiers in World War I, an all-Black regiment known popularly as the Harlem Hellfighters. This unit is notable both because of its huge role in the war itself and because of its place in the history of civil rights. We'll get to all of that in a bit, but it's also notable because of its most famous member, James Reese Europe, a composer and bandleader who in the course of fighting in France, both introduced Black American music to the world and revolutionized its sound.

To talk about that musical history, I sit down with one of today's most celebrated composers. Jason Moran is the artistic director for jazz at the Kennedy Center and a MacArthur genius among many other fancy things. Thanks to vaccine science, we got to meet in person and at a piano.

Jason Moran: Cool. I want to check one thing before we-- I just want to check my hand. [laughs]

Kai: Please.

Jason: I haven't played today.

[Jason playing jazz piano]

Kai: Jason Moran is so passionate about this history that a few years ago, to mark the centennial of the end of World War I, he toured all around Europe playing a concert he created to honor James Reese Europe and the Harlem Hellfighters. James Reese Europe, you have called him the 'Big Bang of Jazz'.

Jason: Yes, I like him. I like him as the 'Big Bang of Jazz' because there's so much that he outputs in his short lifetime that then becomes the strands that everybody can pick up. Louis Armstrong picks up the strand of what it means to be a soloist. Duke Ellington picks up the strand of what it means to embody a Black sonic history and then impart it to a Black orchestra, making the big band a thing about Blackness.

Also, there's the activism model, which is James Reese Europe trying to take care of African American musicians offstage, and the demands on equality. Those things, all of the strands that we're still picking up today, and maybe the most important one is him bringing the music outside of the country. Him, by virtue of World War I, bringing the music to France and then dropping this new idea on a population, like, "This is the possibility of the music."

Kai: Before he heads off to France, what was his music like pre-war? What was he playing?

Jason: Well, he was called the king of syncopation. What that means is there's ragtime music that exists before him, that he grows up in. This is mostly-- People know Scott Joplin's music. Then James Reese Europe comes along and says, "Okay, we can spread it out to further than just the piano. Let's spread it out to 60 people, 100 people, 160 people." He keeps envisioning something larger, but also knowing that, "This is going to expire. There's something else that we have to tease out about how complex we are as people and we have to seek the freedom of what we can't experience in person on the stage."

Kai: Give us a taste of that. What would the ragtime sound like, and then where is he taking it?

Jason: Sure. I'll try, because for all the Joplinites, they'll be like, "Hey, that's not the right notes."

[laughter]

Jason: Joplin is writing like, let's say, the Entertainer is like-

[ragtime jazz playing]

Jason: I already added some Thelonious Monks and stuff in there.

Kai: [laughs] You just can't help yourself.

Jason: I'm sorry, yes. It's just my hand is not a robot, but what James Reese Europe does is just a song called-- It's like--

[playing the song]

[music]

Jason: He is moving it. Also, he's writing these songs with people too. That song is written with Chris Smith. He wrote many songs with Noble Sissle. He's also doing this model that Duke Ellington picks up when he writes with Billy Strayhorn, showing a compositional camaraderie, saying, "No, this is a shared language. I don't need just my name on it."

Kai: He becomes the first Black jazz artist to play at Carnegie Hall too, right?

Jason: Yes. That's before the war, yes. He's not alone in this. There are many composers, many composers of that era who are trying to force this issue, a recognition about what we can demand on the stage that isn't bound into a flatness of Black face. He's trying to make sure that there is an understanding of this. His premier is-- There's this frenzy of a crowd who can't get in to Carnegie Hall.

Kai: Because they don't let Black people in.

Jason: Well, no, it sold out.

[laughter]

Jason: Black folks was in that audience that night too. In history, we sometimes also flattened the line. Oh, Black folk couldn't do X. Meanwhile, Black folks were doing X. He's-- I don't know, what I say is, [laughs] he's so famous. He's like Kendrick Lamar. He's doing what he wants to do, and then by the time the war happens, he envisions something much larger than he's experienced in his fame already, and he says, "No, there's something else to test in this music," and he looks for it.

Kai: He signs up for the-- New York's got this elite National Black Guard, a unit of the National Guard that's all Black. He joins as the war recruitment effort builds and he is given the job of creating a band for the unit.

Jason: Right.

Kai: Tell us about that. What was this band supposed to be doing? Part of it was recruitment, right?

Jason: Part of it is recruitment. He initially also wants to sign up to fight. [laughs] He doesn't necessarily want to go sign up to lead a band. It's that when they see that this famous musician has sign up, they say, "Oh, you know what? We should have you lead a band." Then he gives them an astronomical number to say, "Well, if you want that, then it costs this much.

Kai: [laughs] Really?

Jason: Yes, the equivalent-

Kai: I didn't know this, he charged them.

Jason: Yes, he charged them. [laughs]

Kai: You've got to get it James Reese Europe.

Jason: This will be an equivalent of $250,000 today. He said it like, "You'll never pay that," and he went back to Noble Sissle who was his right arm, and he told Noble Sissle, "I told them what it costs." Then the next day Col. Hayward wrote, he was like, "Hey, we got the money from one guy, and so let's get this happening." Then there's this thing that happens, which is James Reese Europe, he starts putting his band together and they also go play some of these songs in the neighborhood and say, "Look, we're here, we're going to go and maybe you all can join us."

[music]

Kai: Now, understand this moment in American history. It's maybe a generation since reconstruction fell apart and the white backlash to emancipation set in. There's a hardening pseudoscience of race. There's a biological fiction of race, which as Black people are genetically inferior. Black elites, they see the war as a chance to prove our excellence, to prove our right to full citizenship. There's genuine optimism about that possibility. People like W. E. B. Du Bois are really encouraging Black people to sign up in the fight. James Reese Europe wants to do his part as an artist.

Jason: It's that moment where we see how music, and specifically how Black music is used to sell ideas into a community; ones of promise, ones of regret, dread, what the blues still means and listening to it across the country. James Reese Europe, one of the songs he plays is one of these W. C. Handy blues'. When you go into a neighborhood and there they are and you hear that music, which is also new revolutionary music. It's not old school music they're playing, they're playing your music. It was like Sun Ra saying, "Come join the war."

Kai: Come join the war. Can we hear some of that?

Jason: Let’s see.

Kai: At that time, if I'm standing on a corner in Harlem and along comes them trying to get me to come to join the army, what am I going to get?

Jason: It’s like-

[piano playing]

Jason: It's like that song is the blues that keeps migrating. Part of what we learned about the blues or of the many things that we feel in the blues is that there’s always a root there. That's the thing about it. It never tries to hide where home is. That's what also makes blues so confrontational to listen to, is just interrogating the home, but in that song, that blues keeps modulating.

Kai: Say more about that. What do you mean? Help me understand.

Jason: When I think about being from Texas, hearing the blues all when I'm growing up, hearing Lightnin' Hopkins who's from my neighborhood, what he sets in those songs, and every blues musician has set is a reflection about home. When I say home in the music sense, that's the bottom note that will always make sense no matter where the song goes.

[piano playing]

Jason: Back home, and it's a revolution that happens, like that relationship to home is quintessential to also what James Reese Europe is introducing to the community saying, "I know I'm about to take all of you all back across the water, but we're going to play the music that's going to tell us where home is."

Kai: That’s powerful.

Jason: It is. James Reese Europe knows that the blues are an important and integral part of getting soldiers to sign up, so he takes the blues to the neighborhood and people sign up.

Kai: With the armed forces, they were not into this at all. Even those who reluctantly embraced it, they wanted to maintain the segregated post-reconstruction society that was really still taking shape. White leadership took every opportunity to undermine and dehumanize these Black troops. For instance, when the 369th was set to fight alongside the French, the Americans were so nervous about the deployment that they circulated a trick communicate to French line officers written as though it was coming from their own commanders rather than from the Americans.

It warned that Black people were, "A constant menace," that Black troops should not be, "Spoiled. We must not commend to highly the Black American troops," it read, "Especially in the presence of Americans." I often wonder about how soldiers like those in James Reese Europe's band processed all this nastiness because they were sent off to fight in somebody else's war.

Jason: This is one image that I love seeing is, James Reese Europe actually standing in front of the Clef Club, there’s this huge orchestra behind him, and he's got this crate with the American flag draped on it, on the floor as if it's a coffin, but it's also where he stands when he conducts.

Kai: Oh wow.

Jason: Just in that image, you understand so much about what is at stake for them, and this is before the war, but he's like, "No, there's something about this that in this image, I think, encapsulates the uneasiness of what they are now committing to."

Kai: I can never get past when I think about that moment in that era, the deep belief of so many Black people and so many of the individuals who are going to war, and the optimism in the act that, "Oh, once we do this, then we'll be able to set America off on the right course. They'll start to understand that we're human beings." What I know from history about how naïve that optimism was is heartbreaking.

Jason: It is heartbreaking. Then, what is the possibility that each one who signs up for this war is looking for? I always think what we constantly are given throughout history is examples of people that despite how terrible the country is, they like, "No, but that's not my promise." My promise sometimes live in the song, and I can't take the promises not given to me in this country as law. I have to imagine something else.

Then what does it mean for soldiers to say, "Well, despite the country's ambivalence towards me, I'm going to show you actually what my promise is"? I'm also thinking mostly about them on the journey back across the ocean. That's what I'm thinking about. There's a couple of accounts, but one Noble Sissle, James Recce Europe right hand, and he talks about that ride. He talks about them having to be at the bottom of the ship, with no lights on, playing these slow soft songs for each other back across this ocean. That sends me in chills.

Kai: Yes.

[music playing]

Jason: This is what, they're the back of the tomb again. I also wind that up in this history a possibility for people who are trying to make sure that they live up to what they have in their own minds, despite what the country says is their limitation.

Kai: What's nice about this particular story is, it's an example of the maxim that the truth will always come out, because James Reese Europe and the 369th blew the minds of the French. You know how throughout the 20th century there was this odd cultural romance between the French and Black Americans? How Black intellectuals and artists would leave here and go live there and the French were obsessed with their work, and jazz in particular? All that started when the 369th showed up to fight.

They arrive and amongst the things that happens is that James Reese Europe’s band is set to tour the Front, as I understand it, and that's the moment that the French are like, "Whoa, who is this? I don't care what the Americans said about these people, this is some other stuff."

Jason: This is, yes.

Kai: That tour, what music were they playing then? What would the French have heard that became so overwhelming to them?

Jason: Well, the one piece of music that blows their minds is the Marseillaise. James Reese Europe does a remix of their national anthem, that when the audience is hearing it for the first time they're like, "Okay, that's nice." Then they realized, "Oh, this band has done a remix of our own anthem in a way that is like-- How are they doing this?" So much so that they're overwhelmed that people are walking up to the instrument saying, "The trumpet doesn't really do that. The saxophone, this must be a trick instrument that you are making these kinds of sounds with these instruments."

It's that kind of imagination that is different when you have a soloist like Louis Armstrong, but now you have 60, 70 people all at this extreme technique that is on display with also this kind of true understanding of like, "No, this is what this music means."

Kai: It's worth noting, by the way, that this tour also marks the beginning of a tradition that persists today. The average jazz band does way more touring in Europe than it does here in the US, but the sound of that first tour, with that remix of the French national anthem, it's lost to history.

Jason: No one can hear what he did with that song. There's just accounts of what he did with the anthem. It's like, let's say, when we heard Jimi Hendrix play the anthem, we were like, "That's quite an imagination of the song," but also tells us what time it is. Also, part of what James Reese Europe had been doing for decades was teaching musicians how to get effects out of the instrument. Even the concert at Carnegie Hall, many musicians didn't read those charts he had, so he taught them note by note. We're seeing an invisible technique, a thing that is not written on the page.

When you listen to the one recording that we have from his celebration tour afterwards, you hear embouchure in the brass musicians that is so impeccable, that when I play it for musicians who are playing the charts today, they're like, "Oh, yes, I can't really do that." I'm like, "No, but they were doing that back in 1980."

[laughter]

Kai: How come you can't do it now?

Jason: I was saying like, " Didn't we move forward?" Maybe what you're touching on is, we're talking about a technique of our heritage. That technique does not always exist in a conservatory, and so that technique is passed down in the neighborhood. The sounds of the neighborhood then are the things that impact the sound of how I phrase these 4/8 notes. There's a certain rhythm that I feel on it, because that's what my neighborhood sounds like.

Kai: Homemade. It gets back to that home thing. A few months ago, we talked to a cultural historian Saidiya Hartman. She talked about Duke Ellington hearing the sounds and the shafts of the apartment buildings in Harlem, and that that informed the cacophony that he would bring to his compositions. That's just such a beautiful idea, this bringing the actual lived Black experience into this music that became so definitive to the Black experience.

Jason: There's something about hurdling that idea that is worth sharing with someone else. It's worth sharing the sounds from the airshaft with an audience. It's not just this thing that just lives behind my house, or for Howlin' Wolf when he plays a song about the backyard dog, like, "No, it's worth you hearing what a third ward Houston dog sounds like that's on the street at twelve o'clock midnight. I should share that with you." What these soldiers are also saying is that, "You understand what our humanity actually is. With all your lies that you've given us, this is where our humanity lies. This is what we want to try to put on Front Street for you."

Kai: This is the United States of Anxiety. I'm talking with jazz pianist and composer Jason Moran about the legacy of James Reese Europe, and how Harlem's 369th regiment changed everything about American music when they shipped out to fight in World War I. Stay with us.

[music]

Hey, this is Kai. Just a quick program note here. When we started making this show back in 2016, we were just trying to bring context to that while the campaign season, and particularly the history that we all carried into it. Initially, we figured we'd stop after that election, but obviously, there was a lot more to chew on, which is just to say, if you're new to the show, there are tons of episodes here that I hope you'll check out. We've taken snapshots of the political culture.

[music]

Speaker: It's not right, I'm sorry. I feel bad for people that are oppressed, and I mean oppressed, but we got to take care of our own too.

Kai: We've asked how power is really built in a democracy.

Stacey Abrams: I don't believe the demography is destiny. I think demography is a pathway, but it takes work. We are the first campaign in the deep south to put in the work.

Kai: We've just mined all kinds of history in an effort to put America on the couch, to understand how we got here as a country and where we're going. I urge you to dig around in the archives. It is all still relevant. If you hear something that raises new questions for you and you want us to follow up on that, hit me up. Email me at anxiety@wnyc.org and maybe we'll take you up on it. Thanks so much.

Welcome back, I'm Kai Wright, and this is a special Memorial Day weekend edition of the United States of Anxiety. We're on break. I'm probably at the beach right now, actually, but I'm sharing a conversation we recorded with jazz composer and pianist Jason Moran, who shares my passion for the World War I history of the 369th regiment. Earlier in the show, we talked about the history of the song Taps. Jason says the 369th band came up with their own way to memorialize their fellow service members.

Jason: One of the things that we hear from Noble Sissle that when soldiers would not return from the battlefield, they would play the song Flee Like a Bird. It's is very somber-

[music playing]

Jason: He's laying soldiers to rest, but also, he's playing songs for soldiers who are unsure if they're going to return from the battlefield. He's got something for their souls if they don't. Do you know what I mean? Earlier today, I was listening to someone talk about the need for the ceremony around the dead, and in the situation right now, it's been very difficult to have a ceremony for all that have passed away in the past year and a half.

When I think about James Reese Europe playing this song, he's also acknowledging that they won't get that ceremony, that body won't get that ceremony, the family won't get it back home. In this moment, let's alter the program to make sure that we give the ceremony to our brother. Then the bridge of that song, when it migrates just for a second to something brighter, I always think that, really, they're trying to let the soul go in that moment. I wish we could hear a concert, like really how does he plays it in order? Do you know what I mean? What song goes by the next song, and by the next song, and then where does he want to take us? When is the feature for the two drummers?

Kai: Because these would be concerts for troops, for our soldiers, and so, where would he put the mournful march, and where would he put the thing that would say, "We've got this." What's an example of that? Did he do work that was like, "You know what? This is also freedom. We are here about freedom"?

Jason: The song that was my first hook was a song that he was adapting called Russian Rag. It's called Russian Rag. It's big. It's like-

[music playing]

Jason: It's massive. That's the one thing, is it's hard to understand now the scale of the sound. I just can't imagine it. Actually, there are times I can actually imagine it is when we hear HBCU marching bands. When you hear that trombone section blasting, what they're capable of doing, that's the mass of sound that we should understand that this band is playing with, a kind of a bravery that you hear, because you have to convince someone like, "We all--"

Kai: And listen.

Jason: Yes, like, "I'm going to convince you that this is a good idea."

[laughter]

Kai: You go out here and maybe get killed. The regiment turns out to be-- We should point out, it's the most decorated battle regiment in the whole of the war, and stood on the front line 191 days longer than any other regiment in all of the American or French army.

Jason: Yes, receiving the medal of the Croix de Guerre from France. [laughs]

Kai: None from the United States.

Jason: None from the United States.

Kai: France gave 170 members of the regiment its version of a Distinguished Service Medal. The Germans are actually the ones who dubbed them 'the Hellfighters' because of one particularly remarkable battle, but in the United States, their service went unrecognized.

Jason: That is one of the many burns. This is one of them. Even to this day, people are still rallying for an understanding of what the 369th really meant to the country. It's not what they meant to the war, it's what they meant to the country. The ideas that they are proposing about a kind of bravery and a kind of citizenship to a country that still's like, ehh, you know? And it's that robbery which we still see on display daily in the country that still worries me, about how we might minimize the valor of these soldiers.

Kai: You mentioned syncopation. That's one of the things that he brought into the world for the French, the syncopation. I've heard you talk a lot about just it as a metaphor for the for the United States. First off, can you demonstrate what we mean by syncopation, and then tell us what that means to you, what it's a metaphor for?

Jason: I demonstrate it playing something straight. I'm going to try to, at least.

[laughter]

Jason: I'm going to try to demonstrate playing something straight and then playing something syncopated, and I'm going to try to keep the same phrase as I do it. This might be maybe something like-

[playing straight version]

Jason: This is the straight version, but the syncopated version might be-

[playing the syncopated version]

Jason: Everything [singing beats] is getting there before the downbeat. What I say about syncopation is just the anticipation. American move too slow, so the rhythm is, "I'm have to get there sooner." It's just Black folks saying, "I have to give you the idea that we need to move this along a little bit faster." By the time Louis Armstrong arrives 10 years later, then we hear it in full display. He's like, "Yes, now I got what you mean, James Reese Europe. This is how this goes."

In the 19 teens, we hear a syncopation really becoming the idea of the future, which then becomes the seed of what the Harlem Renaissance becomes too. The arts will always give us that first clue as to something that's about to happen.

Kai: Yes, I've also heard you talk about the solo in jazz and what it means and how we misunderstand it.

Jason: The power in the solo is the moment that you can say what do you feel about this song right now. Do you like it, let me hear that. Do you hate it, let me hear that. You think it could sound better, let me hear what you think. The thing is also, this is a moment where I say Black-Americans are not like-- You can't just walk on the street and tell us what you think about everything. You can, but there are repercussions for it from a white danger that is persistent. In those solos, though we think they're obvious parts of jazz culture, politically, it's saying, "No, I have a lot to say and you might not understand it either and it's okay."

John Coltrane, probably, for me, becomes maybe one of the best models of it in the '60s when he's playing a 28 minute saxophone solo. Coltrane is saying in that moment, "I'm not finished." [laughs]

Kai: "You just have to listen to it, I'm not done."

Jason: I'm not done.

Kai: I think of James Reese Europe and the idea of, "We're going to have a big band, we're going to be big, we're going to be overwhelming," this is ambition personified at a moment in Black history and Americans who are Black people are saying, "No, we're going to prove to you how great we can be." Then by the time you get to Coltrane, you get to the '60s it's, "Shut up and listen. [laughs] It's an individual thing.

Jason: It is.

Kai: "You know what? I need to talk to you about something."

Jason: "I need to talk to you." My idea is, they might sound abrasive, but look outside, it's abrasive to everyone in my community. I remember hearing some students really listen to Interstellar Space by John Coltrane and say, "Oh, he sounds angry," but I say, "Do you know what year it is? Do you know what's happening to Black folks? Do you know the kind of white terror that is just on display?" What are we supposed to do, walk into the studio and make something sensitive, that then disregards that this is happening out on the streets? No, we're incapable of doing that.

I'd say that one thing that gets pulled away from the music and conservatories is the activism model that existed in let’s say a Max Roach, an Abbey Lincoln, a Nina Simone. It's not really firmly attached to the songs that we've learned to play. At that part, now we must, for the future of the music, understand the sacrifice these musicians really put out publicly. James Reese Europe becomes like an emblem of that kind of thinking, but also, he only made one record. [laughs]

Kai: He died-- Was it three months after he got back from the war? He returns a hero and an international celebrity and died.

Jason: Yes. He's murdered during a concert in Boston, at Mechanics Hall, during the intermission. He was backstage greeting other musicians while the great singer Roland Hayes comes to visit him during the intermission, because he's James Reese Europe, people come see that. He's also there to do a dedication to Black soldiers the next morning in Boston for a statue, but he's stabbed by his drummer in an altercation during the intermission, and stabbed in a way that he thinks, "I'll survive this neck wound," I think because he's seen the worst of wounds in the war. He's like, "Just continue the concert and we'll meet up tomorrow," and he doesn't live through the night.

[taps playing]

Jason: There's one image of Duke Ellington standing at the grave of James Reese Europe giving flowers. I think what Ellington sees in James Reese Europe is this expansive model. It's why Duke Ellington is known. He's a great pianist, he's one of my favorite pianos, but we really know him for having an orchestra. One of James Reese Europe's thing was like, "We should have orchestras, we should have Black-American orchestras playing Black music the Black way." He says that.

Kai: Ellington brings that to life.

Jason: Ellington makes it like, "I got you." There's just something about what that music means and what that story means, and that has also been quite absent in a jazz history, that I'm really trying to also be a mouthpiece for.

Kai: I asked Jason where he thinks the music's at today, more than 100 years after James Reese Europe's Big Bang and at another moment in which there's a new Black politic emerging.

Jason: I'd say one part is within jazz canon, there is an interrogation of the system itself. There's an interrogation of the misogyny in it, the deletion of the female in it. These systems are also controlled by a white patriarchy. Now we're not only just looking at it out in that world, but let's look at it in our jazz canon too. I think we're on the cusp of another renaissance just because history tells us this, that we've been locked up a year and a half, and there's lots of minds who have now digested this without any fonder of, "It's all glorious." No, it's just isn't.

I put out a record earlier this year called The Sound Will Tell You and it was made in the past year, and it was all mostly slower music. I liked it because it actually acknowledged a darker sense of myself that I probably admitted it in doses on records before.

[laughter]

Jason: This one I gave over to it, because I think a lot of us were in that space. Also, for me, I love working with young musicians, trying to help empower them through a really dark time in history. That music, though it seems inconsequential, that it actually is a vitamin that people desperately need.

Kai: Thank you so very much for this.

Jason: My pleasure, Kai. Thank you.

Kai: Happy Memorial Day.

Jason: Same. Thank you.

Kai: The United States Of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios, Hannis Brown mix the podcast version. A special thanks to Joe Young for help producing this episode. Our team also includes Carolyn Adams, Carl Boisrond, Emily Botein, Karen Frillman, and Christopher Werth. Our theme music was written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band. Veralyn Williams is our executive producer and I am Kai Wright. You can keep in touch with me on Twitter @kai_wright. As always, I hope you'll join us for the live show next Sunday, 6:00 PM Eastern. You can stream it at wnyc.org or tell your smart speaker to play WNYC. Until then, thanks for listening.

[music ends]

Jason: I want to play two themes for you, just so you have them.

Kai: Yes, please.

Jason: One of them is based on a small section of this very weird song he played called Plantation Echoes. Very strange odd medley of racist songs that he put into a song called Plantation Echoes, but in the middle, there's just this gem of two bars of music that I couldn't help but obsess over. It sounds like this.

[playing music]

Kai: Wow.

Jason: I feel like he just plants it. He just slides just two bars. For me, it was 2:00 in the morning listening to that, and it just like jumped out like a bud in springtime. You're looking at this like stump, and then all of a sudden, out comes this indigo. You know what I mean? You're like, "Oh." It felt like that.

Kai: Try to describe for me the indigo that you're hearing. What is it about it that in it made you-?

Jason: When you listen to this song, it's clipping along as if you're watching Birth of a Nation, which happens later. It's as if you're watching something like, "Why are you all playing this? Why are you showing this?" The song is just happening. It's fancy, but it's a fancy kind of idealized racism, like perpetual plantation models all over the country. You hear it, it sounds like that, and then all of a sudden, comes bursting through. Wah wah wah wah wah. And it's like, "Wait, what is that?" Then it goes right to another song, like Dixie or some weird song like that. For me, it's like, "Wait, what did you just plant there?"

Kai: What did you just plant?

Jason: He just plants it as like any great composer, they don't even obsess about it. They're like, "Yes, whatever." [laughs]

Kai: What do you think he was trying to say?

Jason: I don't know.

Kai: Or is that the wrong thing to ask of a composer?

Jason: I don't know what he was trying to say, but when I heard it, I was like, "Oh, that is the gold." It's almost that he places it in the transition, which even makes it more powerful. It's like the break beat. You get producers obsessing over records, finding some weird Ahmad Jamal record and listening to it, and then they just hear just that sliver and then Premier or Pete Rock says, "I'm going to sample that for Nas." You know what I mean?

Kai: Yes.

Jason: And when that moment happens, that's what James Reese Europe also plants in that music too, is like, "No, these can have all kinds of flavors, but then I can introduce just for a second something unbelievable, where it just kinda keep it moving.

Kai: I felt my chest opened. The emotion of it for me is-- Maybe it's because you gave that description of what it was surrounded by, but it felt like a swagger, like a, "You know what? I'm free of that." I'm free of that is what it felt like.

Jason: That's it. You help pull out the fact that maybe him slipping that in the transition-- When I talked about all those phrases and those terms in Black music, him putting it in the transition, he was like, "No, that's the freedom model." He, "Don't just think that it's the song, but even in that little moment to get from section to section, in that transition is actually the freedom, is the breathability of it. It's actually what we hear when we hear Billie Holiday 20 years later pulling at the rhythm of those songs. She's showing the flexibility of the model in a way that nobody had done before.

It happened for the rest. In all great Black music, we hear the beauty in the transition. [laughs] I wanted to make sure I played that for you all, because that's my latest great treasure. I'm so happy about that. [laughs]

Kai: Thank you. You said you had two treasures. Let me hear the other one. Again, we are on your time.

[humming]

Kai: I’d pay a whole lot of money to hear this.

Jason: I'm just going to play the intro to it, but this is a song called All Of No Man's Land Is Ours. He writes this song when he's in the hospital. It was a song he had begin writing-- He had written songs on the battlefield, so he also has the soldiers sometimes make the sounds of the battlefield. You hear rockets, you hear charging. What the war actually sounded like, they put into the songs, but he writes this melody at the beginning, and it's like-

[playing the song]

Jason: All of no man's land is ours. He was like, "Yes, no. All of no man's land is ours. We're about to come.

Kai: Is ours. We're coming.

Jason: We are coming to push the front line."

Kai: He writes it from the hospital.

Jason: He writes from the hospital. There's something about where composers write from. Are they in a nice cabin by the lake, are they in the hospital recovering from mustard gas wounds? Are they in Compton? You know what I mean? Looking outside, hearing the helicopter. Where are the composers writing from? James Reese Europe always has something nearby to document the moment in the sound. Just hearing him play, that's the sound he was hearing.

[music]

Joe: Yes, that's it. This is the phrase he hears first.

[music]

Joe: That's how a song starts. I don't know, just for a composer to be that delicate in that moment, but then move it to all of no man's land is ours, I don't know, he's unafraid to document the moment. I think for all artists, that's the thing we battle with most, is when is the appropriate moment to share or to put it down on paper and then have to stare at it?

Kai: What do you mean?

Joe: Well, any composer, when you write the song down, it's also staring back at you. When you put the pencil to the paper or you write your first lines-- Toni Morrison writes the first line of a novel, after she types it, it shows up, it comes up the line and then also those words are staring back. His phrases, his ideas, his mind, his image is staring back at him in that moment. It's a mirror, those compositions become.

Kai: He's got to be ready to see that.

Joe: He's got to be ready to see it, whether he's actually psychologically ready or not, but I think since he's with a group, then they can do it collectively together. That, I think, empowers him. I don't know if he knew that that would be part of the major part of his legacy, but I think that was the part he was wrestling with when he signed up, was like, "Okay, so I'm going to do this. I know I lead people and all." Every leader, every once in a while is like-

Kai: Is this it?

Joe: -"Is this the one?" Okay, I'm done you all. [laughs]

Kai: Oh, man. I'll treasure.

Joe: Thank you all for being patient.

Kai: Thank you so much.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.