Bias in A.I. and the Risks of Continued Development, with Dr. Joy Buolamwini

[MUSIC - Jared Paul]

Suzanne Gaber: What do you think of when you hear the term artificial intelligence?

Speaker 1: That's a big question.

Speaker 2: Not natural.

Speaker 3: Computer advancement, how it's going to take over the world. [laughs]

Speaker 4: Something that can be used for good and bad, depending on how you use it.

Speaker 3: Like online, you have artists that are upset, that people are making songs in their voice and in their name. There was one show that I didn't watch because the intro was done by AI.

Speaker 4: ChatGPT. I know lots of people use it. I honestly don't use it. Don't trust it. I don't feel like I can get that much efficiency out of it.

Speaker 1: I appreciate all that it gives to us on a daily basis, but I'm afraid of potential possibilities. I'm not really sure the outcome, but I guess it'll be an adventure getting there.

[MUSIC - Jared Paul]

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright. Welcome to the show. As far as I know, at least, nothing that will happen over the next hour has been generated by artificial intelligence. I promise. I think. Artificial intelligence, until quite recently, it seemed like the phrase could be used as an inkblot test. Whether it made you feel excited, or terrified or blase, probably said something about your relationship to the digital age more broadly. I will out myself as among the terrified. I'm skeptical of tech companies in the first place, and I grew up watching the Terminators, so I feel like I know how this movie unfolds.

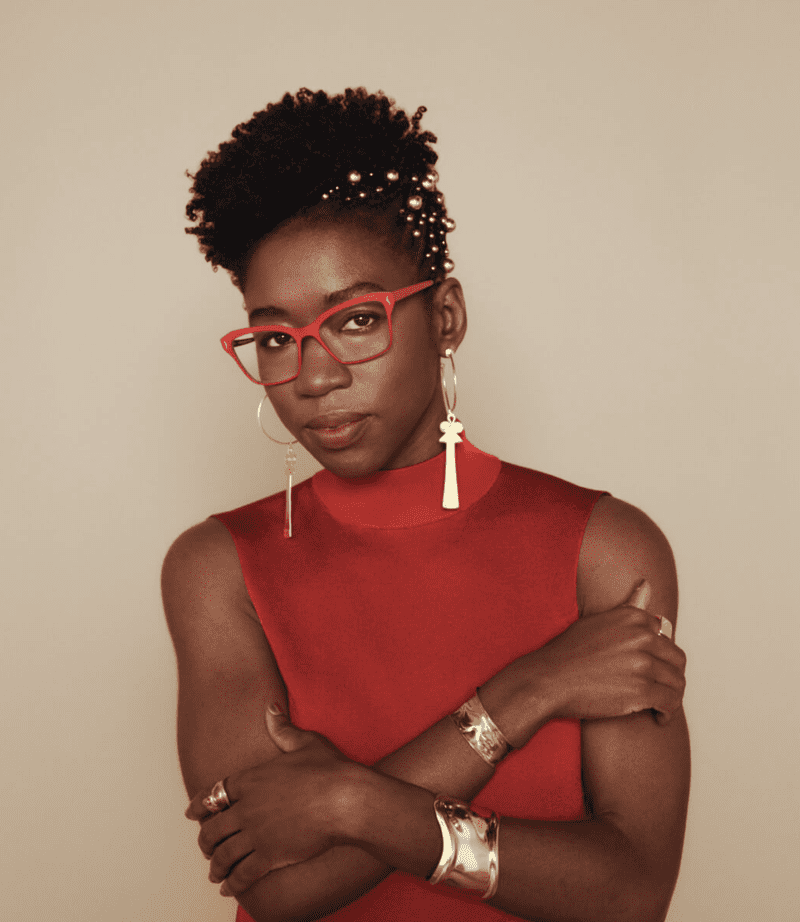

Anyway, like I said, until quite recently, this felt like just a fun parlor game. Throw out artificial intelligence and see how we each react. Now, this doesn't feel like a game anymore. After more than a decade of tech billionaires jockeying to control whatever market AI generates, the fancy full technology has grown quite real. A lot more people are probably in that terrified camp. My guest this week wants us to think less about the Terminator and more about very real-world and present-tense threats. Dr. Joy Buolamwini is a computer scientist whose groundbreaking research help establish the ways in which tech products both reinforce and react to our existing biases around race, gender, and more.

She's the founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, which uses both research and art to educate us all about technology, and in a new book, she tells the story of her research and her advocacy and her life. The book is called Unmasking AI: My Mission to Protect What Is Human in a World of Machines. She joins me now to talk about it. Thanks so much for coming on the show, Dr. Buolamwini.

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: Oh, thank you so much for having me.

Kai Wright: You began your research on bias in AI in 2016. You've since become very well known for this work, and you even advised the White House on its AI policy as I gather, but you kind of came at this, I want to say by accident, while doing a fun project in graduate school. Can you tell us the story of that project and what you discovered that set you on this path?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: Yes. I was very excited to be at MIT Media Lab, also known as The Future Factory, trying my hand not making the future. I was working on an art installation that was an interactive mirror, and the idea was you would look into this mirror and it would actually project onto your reflection anything you would like, so you could look like a lion. I wanted to look like Serena Williams, so I had that as a digital, greatest of all time, why not? Maybe Coco Gauff now, choose your favorite athlete.

Anyhow, as I was working on this project, I wanted this digital filter to follow my face in this interactive mirror I was making. That's where AI comes into play. I decided to get some face-tracking software. When I moved my face in the mirror, Serena's face would follow me too. The problem happened is that the software I downloaded to do this didn't actually detect my face that consistently until I put on a white mask. My dark skin face, not detected consistently. This lifeless white mask detected almost instantaneously.

In having that experience of, in a sense, coating in white face at what's meant to be this epicenter of innovation at MIT, that's when I came to face with what I now call the coded gaze of just this questioning, are AI systems neutral? That would've been my assumption to begin with, but this experience really led me to start exploring that question more.

Kai Wright: I have to ask and so, I should say on the cover of your new book, it's a picture of you holding a white mask. I have to ask, what made you think of the mask when you were in that moment? What made you think, "Maybe if I put on this mask?"

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: That's such a great question. It was around Halloween time. I happened to have a white mask because I had gone to a party and I thought, "Oh, let me have the mask for the party." It just happened to be leftover from the party. In fact, before I even tried the white mask, what made me think, maybe let me try a white mask, is I drew a face on my palm. Just like a cartoony smiley face. The face on my palm was detected when I held it up to the camera. Once that happened, I was like anything is up for grabs, and literally the mask was right there. I thought, "Why not? Let's just see."

Kai Wright: I wonder, this was obviously such a provocation because so much has happened from that moment for you and for all of us given your research. I wonder what that felt like in that moment to be sitting there thinking, "Ooh, I want to look like Serena," and not be recognized, but put on a white mask and be recognized. I just wonder about that moment for you emotionally.

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: At first, I was in this debugging mode, so it's not working. Now it's exploratory. That's when I draw the face, like the face on my hand, that was cute. The white mask, not so-- [laughs]

Kai Wright: Now you're getting a little more frustrated.

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: Not so cute. Wait a minute. Hold on. Frantz Fanon already said it, Black skin, white mask but it was not lost on me the irony of being in a white mask in also a place that was very whitewashed at the time. I was amused, fascinated, frustrated, all of those things at once.

Kai Wright: Yes. In the book, you talk about your experiences when you first started bringing up this idea that, "Hey, maybe, AI doesn't quite detect darker skin." You said one comment you immediately started getting was, Algorithms are math, math isn't biased." Then you said when you started this research, you wanted that to be true. Why did you want that to be true?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: I think we have to make a differentiation with what we're talking about when we're looking at various types of AI systems, and in particular, the types of AI systems that I was looking at, detecting a human face, then trying to guess the gender of the face, and all of that.

Kai Wright: Yes. Please help me out because I am out to my debt. Help me understand this.

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: Sure. These types of AI systems that have become really popular as of late, are based on this approach of machine learning. The idea of machine learning is instead of trying to explicitly write code for every single way a human face could potentially look like in a digital photo, which is really hard to do and people have tried and it didn't work as well. The alternative was what about we teach the machine to recognize the pattern of a face and to teach that pattern, we'll have a data set of faces. This is where bias comes in. Think of the data set as the experience of the world.

If you have data sets that are largely of lighter skinned individuals, data sets that are largely of men, then that machine learning system is going to have very limited experience. That's where the bias comes in because we are creating AI systems that are essentially pattern recognizers and pattern producers, and then we're feeding them patterns that are based on a skewed representation of the world. I'm not saying one plus one doesn't equal two. I'm saying the ways in which we're applying algorithms to various AI applications introduces bias throughout the entire process.

Kai Wright: That the bias comes from the jump, not because of the math itself. You used the phrase-- I think you made reference to the coded gaze earlier in our conversation. That's a phrase that you have coined. It comes up in the book, you've talked about it a lot. Just introduce that phrase to folks. What is it and why do you choose that phrasing?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: Yes. The term, the coded gaze, is inspired by causing concepts like the male gaze, which was developed by media scholars and art scholars talking about the ways in which women are depicted whether in film or even fine art is often to please a male viewer. There's also this notion of the white gaze. When you're thinking about storytelling, who was centered, which stories are deemed to matter? All of that comes down to who gets the power to choose, who gets the power to prioritize.

When I was thinking about the coded gaze, this was thinking through who has the power to shape the technologies that shapes our lives. In having that power, whose priorities are embedded as well as whose prejudices are embedded within that technology. That's where this concept of the coded gaze emerges.

Kai Wright: Before we take a break because I think it'll be useful for the conversation that goes forward, you also have the phrase ex-coded. Quickly, what is that and how is it different from the coded gaze?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: The coded gaze leads to the ex-coded. The ex-coded is anyone who was harmed by an AI system. That means no one is immune from experiencing AI harm. I like to make up terms, ex-coded sounded like a good one. You could be excluded. You could be exploited in other ways as well. That's where ex-coded comes from.

Kai Wright: Anybody who's been harmed by the coded gaze in the first place.

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: Absolutely.

Kai Wright: Well, we need to take a break. Hold those terms for when I come back. This is Notes from America. I'm talking with Dr. Joy Buolamwini about her new book, Unmasking AI: My Mission to Protect What Is Human in a World of Machines. When we come back, we can take your calls. You can call or send a text message with questions about artificial intelligence, in particular, how it interacts with our existing biases. We'll take your calls and read some poetry after a break.

[MUSIC - Jared Paul]

Welcome back. I'm Kai Wright and I'm talking with computer scientist, Dr. Joy Buolamwini, about artificial intelligence, how it has been shaped by our biases around race, and gender, and more, and how it could reinforce those biases into the future. Her new book is called Unmasking AI: My Mission to Protect What Is Human in a World of Machines. As we talk, we can take your questions about AI, particularly as it relates to Dr. Buolamwini's research on bias.

You can call us or you can send us a text message. Dr. Buolamwini, you bring art into your work as a computer scientist, which is just a fun thing to even say out loud, art and computer science. You're a poet. You go by the title Poet of Code. You have one poem in particular that I'm hoping you can read for us a little bit of. It's called AI, Ain't I A Woman. Could you read that for us?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: Oh, yes. I'm happy to elevate art in this space and do a reading of AI, Ain't I A Woman. Here we go.

My heart smiles as I bask in their legacies

Knowing their lives have altered many destinies

In her eyes, I see my mother's poise

In her face, I glimpse my auntie's grace In this case of deja vu

A 19th century question comes into view

In a time, when Sojourner truth asked

"Ain't I a woman?"

Today, we pose this question to new powers

Making bets on artificial intelligence, hope towers

The Amazonians peek through

Windows blocking Deep Blues

As Faces increment scars

Old burns, new urns

Collecting data chronicling our past

Often forgetting to deal with

Gender, race, and class, again I ask

"Ain't I a Woman?"

Face by face the answers seem uncertain

Young and old, proud icons are dismissed

Can machines ever see my queens as I view them?

Can machines ever see our grandmothers as we knew them?

Kai Wright: That poem, that's AI, Ain't I A Woman. It's based on Sojourner Truth's Ain't I A Woman? poem. You wrote that after realizing, as we talked about, facial recognition technologies are most inaccurate when used by women with dark complexions, which is to say that the bias you found was both about skin tone and gender. Can you tell me about that intersection?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: That's such a good point. One of the big contributions of my research when it came out was showing the importance of looking at the intersections of skin type and gender. Studies before really hadn't taken a look at that intersection in such an explicit way to say intersectionality matters. What I realized, though, with the research I had published was that the performance metrics of saying this AI system from IBM or Microsoft, and then later on Amazon, might have, I don't know, 0 to 2% error rates on lighter skin men, but maybe up to 34% error rates on darker skin women.

It was very clinical. Here are the numbers. I wanted to move from the performance metrics to the performance arts to ask, well, what does that mean? What does that feel like? I started testing the faces of people like Oprah Winfrey, Michelle Obama, Serena Williams, and they were misclassified as men. Ida B. Wells, her photo was described as a boy in a hat, and also by IBM as a coonskin cap. As I was looking at these sorts of depictions and descriptions, Google's describing Sojourner Truth as a clean-shaven old man, that is when the notion of AI, Ain't I A Woman came to be. I was bringing in historic figures.

Ida B. Wells, data science pioneer

Hanging facts, stacking stats on the lynching of humanity

Teaching truths hidden in data

Each entry and omission, a person worthy of respect

Shirley Chisholm, unbought and unbossed

The first Black congresswoman

But not the first to be misunderstood by machines

Well-versed in data drive mistakes

Michelle Obama, unabashed and unafraid

To wear her crown of history

Yet her crown seems a mystery

To systems unsure of her hair

A wig, a bouffant, a toupee?

May be not

Are there no words for our braids and our locks?

As I'm saying each of those phrases, what you can't see just through the words are the examples of each of their faces being misread, being misclassified, being denigrated, and we can get into that terminology itself, by AI systems from some of the biggest companies out there. You had Amazon labeling Oprah male. This is not a case where you can see it say, "Oh, well, we didn't have enough photos of Oprah." When it came to Michelle Obama, her childhood photo, describing her hair as a toupee.

In the book, I write about how these algorithmic insults reminded me of the real-world insults that Black women face. Really, the idea for doing AI, Ain't I A Woman, that is, yes, the spoken word that you heard,. Aso, these powerful examples that you can't unsee while it's going was to humanize the impact of some of these AI systems gone awry, so it became more than an academic exercise.

Kai Wright: People respond to the poetry differently, I imagine, than the research when you're presenting it.

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: It is interesting because I remember sharing AI, Ain't I A Woman actually in the EU in Brussels, Belgium is when I first shared it. Later on, it was actually shared with EU defense ministers ahead of a conversation on lethal autonomous weapons. I shared screenshots how mentioning Michelle Obama being misclassified. Oprah being misclassified, Serena being misclassified. That's in the congressional record for hearings that I did around bias in facial recognition technologies, gender classification and also thinking about our civil rights when it comes to biometrics like facial recognition being used.

What I saw was an opportunity to bring the art and the research together. I would have the numbers from IBM or Microsoft or Amazon or others. Then I would have these arresting photos as well to go with it.

Kai Wright: We're going to talk in some detail about some of the specific ways in which this bias shows up in that you talked about in your book. Just on a fundamental level, the misrepresentation you're talking about, why does that matter? It's a repeating what we're seeing in real life the same misrepresentation we're seeing in real life that same denigration it seems like a basic question but to spell out for people why that matters that that's showing up in technology.

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: I think it's really interesting to look at generative AI systems. When I was doing this research, 2016, '17, '18, so forth, this was before this big release of generative AI systems exploding that we saw a lot of in this year with ChatGPT with things like Midjourney or DALL·E where you can put in text prompt and get out an image for example. To your earlier point, isn't this just reflecting the status quo? I used to think we were looking at a mirror, but what I've come to see is we're actually looking at a kaleidoscope of distortion. What I mean by that, I'll use an example that Bloomberg News did.

They decided to test some text-to-image generators. What they did is they gave text prompts of high-paying jobs and low with paying jobs. Think CEO, high-paying job, think architect, high-paying job, low-paying job, social worker, fast food worker. Then they also did criminal stereotypes, drug dealer, terrorist. Maybe not so surprising. When it came to the high-paying job who do you think the representation for high-paying jobs were?

Kai Wright: [laughs] got to guess. White man.

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: Ding-ding. You are correct. Then when it came for low paying jobs who do you think the representation.

Kai Wright: I'm going to guess dark-skinned women.

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: People of color, more broadly women, showed up there. We were seeing some diversity just in a particular pocket. When it came to representations of criminal stereotypes dark skinned men were there. What I wanted to point out with this particular study to the distortion part, let's take architect. In the US women are around 34% of architects. If you say the status quo isn't great but there was some progress. When they put in the prompt for architect, women were depicted as architects less than around 3% of the time.

This technology that's positioned as carrying us into the future is actually reversing the hard thought progress that was already made. The other part that we have to consider as well is oftentimes when outputs come from computers, they are assumed to be more objective. Even when study after study and all of this research shows that's not necessarily the case.

Kai Wright: Speaking of reversing the other way a straightforward listener question the text message from one of our listeners is can this bias you're describing be reprogrammed? Can AI be reprogrammed so that this bias doesn't exist?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: I often hear people asking about bias elimination, and I think of it more as bias mitigation. As long as humans are involved, there's going to be some bias. Even the types of AI systems that are imagined and made in the world, that design component is influenced by those who have the power to say, "These are the systems we're going to create in the first place." That being said, there is certainly a lot more that can be done to make sure that the systems are more equitable. Let's say you are excited about using AI for healthcare in some domain. It is so crucial that you don't just assume because you have a good intention with using AI in that space. It's going to work well for everybody.

You actually have to go in and be very rigorous with your data collection and be very rigorous with the testing of those systems to make sure that they do what you think they're going to do instead of just hoping they deliver on the promise untested. I think it's important to note that bias mitigation is possible. Bias elimination, I usually say unless if you get rid of the people you're probably not going to get rid of bias completely.

There's another element that I think is really important for all of your listeners to be thinking about which is bias is just part of the concern, particularly when we're talking about the ways in which AI can be harmful. Let's take facial recognition technologies as an example. Let's say we had perfect completely accurate facial recognition which we do not does not exist.

Even if we had that, now you have the tools for mass surveillance. How well these systems work is part of the analysis but how these systems are being used is just as important. Accurate systems can be abused and it can be very tempting to just think, "Okay, we'll make the systems more accurate and we have done our job by looking at it from just a technical lens." You have to think about it societal impact, and hence the social technical lens. Then you have to back up and say should these systems even exist? Should they be applied in these ways in the first place?

Kai Wright: I want to bring in a caller who I think has a question. Along these lines, Wendy from Springfield, New Jersey. Wendy, welcome to the show.

Wendy: Yes just what you were just talking about we want these systems not to recognize us. I don't know the details but a Black man, let's say he lived in New York. He was accused of having stolen a car in I can't remember what state it was. Let's say I'm making up the state. This thing actually happened in Louisiana, and he was put in jail because AI identified his face as the face of the person who had done this while his lawyer went to the state looked at the man, said, "They do look alike. It's a similar face. This man was in jail for a week." It's what you were just talking about.

Let's say it was accurate so we could accurately be surveilled. Do we want this? Do we want to be recognized by these machines? Of course, the fact that he was in a different state and couldn't possibly have done this crime at the time because he was in a different state, they discounted that and said, "The computer identified him so it must be right."

Kai Wright: Thank you, Wendy, and can we get-- We're going to have to go to a break here in a couple of minutes. I know you've got a really important story in your book about the ways in which law enforcement has misused this technology. What about on just that fundamental question of like, do we want this in the first place? How do you answer that, Dr. Buolamwini that just whether it's a good idea at all, whether or not it can be done right?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: In the book I talk about red lines and a big red line for me is the use of face surveillance, which isn't just facial recognition, detecting an individual like Randall Reed. The example you're talking about. A man in Georgia being falsely accused for a crime in Louisiana. He's among the ex-coded. You also have people like Porcha Woodruff arrested eight months pregnant for a carjacking she did not commit. She reported having contractions in the holding cell. She was arrested by the same police department in 2023 that arrested Robert Williams in 2020 in front of his two young daughters all due to facial recognition misidentification.

To me, the answer isn't let's make this technology more accurate for police to use. The answer is police should not be using facial recognition technology not just because it's discriminatory which it is, but also because of the privacy and surveillance implication of its use and the abuse of these systems as well. I do absolutely believe there should be red lines on the use of facial recognition technologies. For me, when it is used in the context of surveillance, when it's used in the context of policing, when it's used in the context of weapons, those are clear red lines.

People should also know that they can opt out of these types of systems. For example, when the TSA adopts facial recognition and doesn't really let people know they can opt out, even though you have a right to. That is also wrong.

Kai Wright: I'm going to stop you there because I really want to learn more about that, but we've got to take a break. I'm talking with Dr. Joy Buolamwini about her new book, Unmasking AI: My Mission to Protect What Is Human In A World of Machines. Listeners, we can take your questions either by phone call or text any questions about AI, particularly as they relate to Dr. Joy Buolamwini's research on bias. Stay with us.

[MUSIC - Jared Paul]

Rahima: Hi, everyone. My name is Rahima and I help produce the show. I want to remind you that if you have questions or comments, we'd love to hear from you. Here's how. First, you can email us. The address is notes@wnyc.org. Second, you can send us a voice message. Go to notesfromamerica.org and click on the green button that says start recording. Finally, you can reach us on Twitter and Instagram. The handle for both is Notes with Kai. However you want to reach us, we'd love to hear from you and maybe use your message on the show. All right. Thanks. Talk to you soon.

[MUSIC - Jared Paul]

Kai Wright: Welcome back. This is Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright and I'm joined by computer scientist, Dr. Joy Buolamwini, author of the book, Unmasking AI: My Mission to Protect What is Human In A World of Machines. She's also the founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, and we are taking your calls. If you have a question about AI, you can call us or you can send us a text message with questions about AI, and particularly as they relate to Dr. Buolamwini's research on bias.

You had begun talking about the TSA as one of the really concrete examples of a place where we encounter AI and things are a little upside down. Explain to me what happens around AI when we encounter TSA and what we should know as individuals who are going through those lines.

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: Got it. Over the last few years, the Transportation Security Administration, TSA, as you all know, have been expanding their use of facial recognition technologies. Last we checked, they were at around 25 airports across the United States, and they have plans to expand it to 400 airports. Essentially, what they're doing is at the checkpoint, right when you're about to go take off your shoes for even more screenings, instead of checking your ID and then looking at your face, what they're now doing is saying, look into the camera. Step up, look into the camera.

This is supposedly a pilot program that's supposedly voluntary. We actually did a campaign this summer asking people about their experiences. Did they even notice that there was facial recognition going to be used, or did it just happened to come upon them once they got to the front of the line? Was there clear signage where they even asked if they could opt out?

What we learned was the majority of people didn't even know that they had the right to opt-out. In fact, on the TSA's own website, the whole thing is supposed to be opt-in in the first place. What we were seeing time and time again from the hundreds of reports we received were that people felt they couldn't say no, or they didn't know they had that option to say no.

If I say no as a person of color, already under scrutiny, already with time pressure, already with the economic pressure of having gotten this ticket, if I say, if I don't comply, will I fly? You have this scenario.

Kai Wright: Exactly. What do you advise? There's so many situations like that where sure, technically I could say no, but it doesn't feel like a real option. What am I supposed to do in that moment? What is your advice for us in that moment?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: I think it really depends on your own circumstances to know what risk you are able to take. I would say those who are more privileged should use that privilege to say no. I also think it's not just on individuals to resist these types of uses of facial recognition. This is actually why we were really encouraged to see the introduction of a bill that says the TSA should not use facial recognition at airports because we do need, at the end of the day, federal protections so that it's not on the individual to feel pressured to go against this huge system.

I would say you have to have a sense of the risk that you are willing to take on. For the most part, from what we've heard reported from those who have said no, they're generally able to opt out once they assert that they know they can opt-out. It's just most people don't know in the first place. I do encourage people to exercise that right to refusal, but I don't think you should beat yourself up if you look around and you say, this might make my day a little [crosstalk]

Kai Wright: This is not the moment. Let's go to Stephanie in Manhattan. Stephanie, welcome to the show.

Stephanie: Kai, thank you so much for taking my call. I'm a financial advisor and I just want to add in extend the concern that you all are expressing so articulately. What I see on the business channels is nothing, not a word, not a peep about the privacy aspect of this new technology. I'll give you a really concrete example because every company comes on and says, "Oh, generative AI." It's their new buzzword.

I think it's very realistic that we would see AI being used for mortgage application decisions. We've already been through many, many chapters of people of color being discriminated in the mortgage arena, for other arenas, for financial products. When I say not a peep, I mean, not even 15 seconds about these companies are under the following regulations to use AI in a responsible manner to not compound these lending discriminations that already exist.

Kai Wright: Stephanie, do you mean that not a peep in the sense of people aren't even thinking about it or not a peep in the sense people can't be bothered?

Stephanie: Both. Let's put it this way, if you watch the business channels all day, no discrimination, there's no privacy concerns. Generative AI is all good. It's all rosy. It's all going to promote positive outcomes for society. I'm listening to this going, hey, wait a minute, this is going to compound discrimination because humans are involved and you are explaining this extremely well.

Kai Wright: I got it.

Stephanie: There's nothing--

Kai Wright: I'm going to stop you there, Stephanie. Thank you for that. Dr. Buolamwini, what about in the financial sector? Are there some examples that you can think of that we need to be worried about?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: Absolutely. The Markup great investigative data-driven publication, they did an investigation in 2021 that showed that there was a bias hidden in mortgage approval algorithms. That loan applicants of color were 40% to 80% more likely to be denied the mortgage application than their white counterparts. That in specific metro areas, the disparity was greater than 250%.

We're talking about people who basically have the same stats coming up. They have the same level of living income and so forth. The difference was race. We are already seeing this impact on the financial side. Actually, Steve Wozniak made some headlines when he was applying for credit and his wife was also applying for a credit and her being a woman, she was not given the same amount, even though they had the same assets because it was all shared. I would just underscore that those concerns are valid. The numbers are there to back it up. This is precisely why I wrote the book, Unmasking AI. Because oftentimes we hear about the promise without addressing the peril. The point of the book was to say, "Here's the other side of it."

Kai Wright: Let's go to Zinnia in Barre, Vermont. Zinnia, welcome to the show.

Zinnia: Thank you. One thing that is already happening with machines as intermediaries and damage to humans that's made worse by AI, and I'm talking about a, "Oh, we didn't do it. It was the algorithm." It's removal responsibility." Whether you're bombing in Vietnam or in Gaza. Pilots are not seen as personally responsibility for the bombs that they've dropped because it was done by a machine, and that, oh, thousands of people are being killed in Gaza by airstrikes. Whereas graphic descriptions of Israelis killed in October. Yes, that was horrible, but it's no less horrible if someone is named or killed by a "airstrike."

I see this as being intensified, this removable of responsibility, if there's a machine intermediary that if it's a computer machine, artificial intelligence, responsibility can be diluted if not entirely eliminated.

Kai Wright: Thank you, Zinnia. I think I got that. Dr. Buolamwini, you have written about and talked about AI in the context of war. I gather actually that you wrote a poem this very morning about AI and war. Would you want to read that for us and tell us about it?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: Sure. This goes to some of the concerns that were just expressed by the caller now. The name of this fresh poem is called Precisely Who Will Die.

Some say AI is an existential risk.

We see AI as an exterminating reality,

accelerating annihilation, augmenting destruction.

I heard of a new gospel, delivering death with the promise of precision.

The code name for an old aim to target your enemy.

The other reduced to rubble.

Faces erased, names displaced as the drones carry on in a formation that spells last shadow.

AI wars, first fought at the doors of our neighbors. Next, the bombs drop on your private chambers.

Kai Wright: The use of drones, is that the primary way in which you see AI showing up in warfare?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: Not only do you have the use of drones, but you also have the use of AI to select targets to be bombed as well. To the point of when you take the human away, and there is almost the sense of moral outsourcing, the consequences of war and that human toll and that human impact become abstracted, almost like a video game. I open the book, Unmasking AI, talking about lethal autonomous weapons. Later on, I talk about the campaign to stop killer robots. Essentially saying that if we give machines that kill decision, it further dehumanizes individuals in conflict situations.

We are seeing AI being used for surveillance, and that surveillance can then be used in policing. It can be used in war. We're seeing facial recognition and biometrics being integrated into different types of weapon systems. Now think of a drone with a camera and a gun. Now add some facial recognition. Accurate or not accurate, you're causing damage.

Kai Wright: Related to this, one of our listeners Alec texts to ask. "In general, I'm curious about the international context for facial recognition. Beyond warfare, are there other ways in which it has international implications that you're thinking about?"

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: I think the big one is borders. You'll see that in some cases, asylum seekers. This happened on the US border where African and Haitian asylum seekers were actually made to use a particular app that used facial recognition. It was not able to verify their faces in the first place. You already had this technical barrier. I do think about migration as an area we see facial recognition systems being used, borders all around the world, for sure.

Kai Wright: As we start to wrap up, you've made a couple of references to what can be done beyond the individual level, and I want to spend some time on that. Earlier this year, the White House announced that several big companies, Microsoft, Google, OpenAI, signed a voluntary pledge where they committed to a number of things that included "prioritizing research on societal risks of AI, including around discrimination and privacy." You've said that is not enough. Why?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: We don't need blue ribbon commissions to tell us that there is bias and discrimination in AI systems. I think that research is important and it should continue. That's research that can happen at tech companies but needs to happen in organizations that are independent of the influence of tech companies. We've seen many AI ethics teams become decommissioned or otherwise expelled. Also, voluntary commitments and self-regulation are not enough. I was very encouraged to see the executive order that came out a little later in the year, because that actually then starts moving towards federal shifts that have teeth.

That executive order was actually based on a blueprint for an AI bill of rights that says people will have protection from algorithmic discrimination, that these systems have to be shown to be safe and effective. I think very importantly, that there should be alternative pathways like with the TSA situation. The default isn't, "I have to surrender my face and give up my valuable biometric data just to fly."

Kai Wright: What about at the state level? There's an executive order from the White House that get things started. There's a bill you mentioned earlier circulating in Congress. What about action at the state level?

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: We see that state-level laws make a difference. For example, in Illinois, there is the Biometric Information Privacy Act. Because of that law, Facebook actually entered into a $650 million settlement for violating BIPA in the state of Illinois. That came because of all of the faces that were used from the Facebook platform to train their facial recognition systems. Probably unknown to you when you were tagging your friends' faces and other things, you could have been contributing to their AI capabilities. That was not done with explicit consent.

We've seen time and time again where laws exist. They are deterrents because not many companies want to have to do the $650 million settlement as you might imagine. Afterwards they deleted over a billion face prints. Laws absolutely matter. We've also seen many wins in the local level, particularly putting restrictions on police use of facial recognition. Some of those campaigns use the research of the Algorithmic Justice League and others. The problem is, we don't want it to be, you have to live in the right state or the right city. It should be protections for everyone.

Kai Wright: We will have to stop there. Dr. Joy Buolamwini is an AI researcher, founder of the Algorithmic Justice League and Point of Code. Her latest book, Unmasking AI: My Mission to Protect What Is Human in a World of Machines, is available now. Thanks so much for joining us.

Dr. Joy Buolamwini: Thank you for having me.

Kai Wright: Notes from America is a production of WNYC studios. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts and at Notes with Kai on Instagram. Theme Music and sound design by Jared Paul. Matthew Miranda is our live engineer. Our team also includes Regina de Heer, Karen Frillman, Suzanne Gabber, Rahima Nasa, David Norville and Lindsey Foster Thomas. Our executive producer is Andre Robert Lee, and I am Kai Wright. Thank you so much for joining us.

[MUSIC - Jared Paul]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.