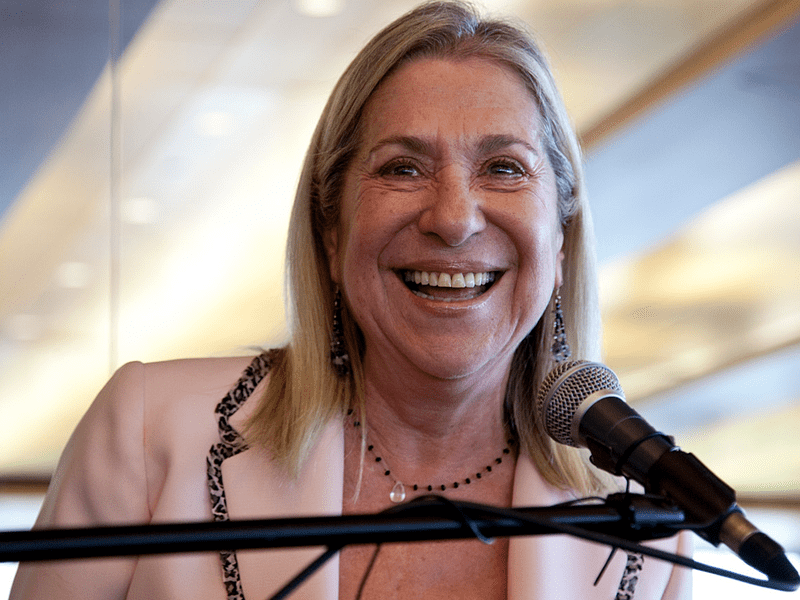

Author Letty Cottin Pogrebin on her Decades of Activism

( Kevin Gay )

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: The wonder of dialogue, and I've been in Jewish Palestinian dialogue and had the same experiences, is that what you think is so obvious gets really questioned at a deep level. And you have to say, I need to see the world through a broader vision. I can't just look at the world as a white woman, and certainly not as a white woman of a privileged class, because I'm missing the reality.

Helga: I'm Helga Davis, and welcome to my show of fearless conversations that reveal the extraordinary in all of us. My guest today is author and activist Letty Cottin Pogrebin, who, for decades, has been immersed in the tireless fight for gender equality and social justice. She co-founded Ms. Magazine, which played a pivotal role in the feminist movement of the 1970s.

She served as president of the Authors Guild and chair of the Americans for Peace Now. She co-founded the National Women's Political Caucus and the International Center for Peace in the Middle East. In our conversation today, we discuss some of the pivotal moments that defined her political thinking, her feminism, and her understanding of Jewish tradition.

She sees her activism as a seesaw, always moving to protect those who are under attack. Let's talk a little bit about the circumstances within the American culture, within the global culture, that fueled your activism. And perhaps continues to fuel your activism.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Well, my activism as a woman, I think, was late in coming, given what I was exposed to by the radical wing of the feminist movement.

There was A lot of messaging coming out, but it was from obscure places. We didn't have an internet. We didn't even have faxes. I mean, all you could do was read position papers that were cranked out on a mimeograph machine in somebody's garage.

Helga: What year are we talking about?

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: I'm talking about, I came to consciousness, as we used to say, in 1968.

I had just finished a manuscript for my first book, How to Make it in a Man's World, and I had been totally blind to the circumstances of most women. I looked at my career at that time. I was lucky. Women say lucky when they really did something to deserve things, but I was. I was lucky that I worked for a boss in publishing who just kept promoting me and I wrote a book about how to make it in a man's world as if everybody had the circumstances I did.

And that's, I think, a real attitudinal problem is that you think what your experience was is everybody's, unless you come to consciousness, unless you make an effort. And so I published this book, it got a great review in the New York Times, and I got attacked by what was called women's lib. I'd never heard of women's lib.

They're all saying you're a queen bee, you're not seeing poverty, you're not seeing the circumstances where women are single mothers, you're coming out of your class. vision of what life is all about. And your advice is perfectly fine for college educated women who have husbands who support them, but you're oblivious.

My editor said, you can't go out on the road promoting this book until you read some of the position papers of the feminist theorists. I was totally dumbstruck that I'd missed this. And who were those women? The Politics of Housework, The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm, T. Grace Atkinson was one, Kate Millett, Shalom at Firestone.

Alice Walker was starting to write, but I mean, I was so far out of it. And shamefully so. I tell this story because I think people still see the world only through their own tunnel vision when it comes to women. Your experience determines whether you're a feminist or not, and that's no longer true for me.

I've gone far out beyond my own experience and made it my business to absorb the reality of the rest of womankind, and that's what made me an activist. I was involved in the anti war movement. I was a big supporter of and marcher for what we called civil rights in those days. And somehow or other, I'd missed women.

I'd missed the whole experience of a wide spectrum of women. So I sort of moved my activism across the spectrum and covered misogyny and sexism and male supremacy in ways I hadn't understood before.

Helga: What I find sometimes is that we speak in these global terms as if conversations about love, conversations about housing, conversations about women's rights, conversations about equal pay, often, I think, exclude Black women in particular.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Well, as I say, I was oblivious to the whole set of issues. All of it. No matter who was involved. I just was totally class bound in my view of what women's prospects were and I had never looked up a statistic on equal pay. I was not a feminist. So for me, I had to educate myself. Let me put it this way. If you are a welfare mother, and you don't have backup for any emergency, okay?

What good is it reading a book about somebody who says, um, well, there are going to be some times when you're not going to be able to show up and, you know, like, what? Why? I'm not going to be able to show up because I have a board meeting? I mean, my blindness was so class bound, so I wasn't really aware of racial differences within my blindness.

But once I got involved in the women's movement, There were black, white, Hispanic, you know, Asian. Everybody was in it. And I think that we were intersectional, but we didn't have a word for it. Because, I mean, intersectionality, as I understand it. It's about linking oppressions, recognizing that you can't separate people according to just one line of identity.

A person who is disabled and a Latina who is also abandoned by her husband or subject to abuse of men, how do you separate out which one's the worst? So that's intersectionality, as I understood it. We were conscious of it, we just didn't name it. We were sitting in editorial meetings. The Ms. Magazine in the 70s and 80s saying, what's in this issue that's going to speak to poor women?

What's in this issue going to speak to people who are disabled? Because the disability rights movement had just started sort of waking up. I'll just divert Helga to tell you. There were epiphanic moments for me. Moments when it was like, click, which by the way was the title of Jane O'Reilly's piece in the very first issue of New York Magazine.

Click being the moment when you suddenly get it. Dawn breaks. And in terms of disability rights, I have such a clear memory when I was the keynote speaker, mind you. I mean, to my shame, at a disability rights movement convention. And I went on and on about how terrible it was for men to make women into sex objects.

And some woman raised her hand in the question period and said, I would like to be treated like a sex object once in my life. She had spina bifida. She was sitting in a wheelchair. Small and partly paralyzed. I can't even describe the situation. I don't have the right language. But I looked at her and I realized, she'd never been whistled at by a line of construction workers.

She would love to have had that. It blew my mind. It made me broaden my vision, my willingness to not just empathize, but enter into the reality of another person. And I think that's a really tough assignment if you haven't grown up with it.

Helga: Yeah, for sure. So you get involved in this movement. You're writing books, you're a co-founder of a magazine, and you have a family.

And you have three children and a husband, and you're trying also to navigate your family life. Right. How did you manage that?

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Not great, but a lot better than somebody that didn't have a partner. My husband, Bert, and I became feminists at the same time, because he was trained at the Harvard Law School to interrogate everything about a case.

So I would come home. With this batch of position papers, theory statements, mission statements from these revolutionary women's groups. And I would read them and, and I would say to my husband, listen to this, this makes so much sense. How come we haven't noticed that we both come home from a long day's work, I cook, I do the baths.

I mean, we both come home, and we're very lucky, because of making a lawyer's income, that we have a caregiver for the children. But I did that because I wanted the parent part to be important in their lives. And he sits down with the New York Times, I mean, really, and literally sticks his feet up. And I was reading it to him and saying, Let's talk about the justice of this for a minute, because I was reading a little shredded piece of paper that said, women wake up, don't let your husbands walk all over you.

That's the original oppression, the one that begins at home, the one you may have grown up with, with a father who sat down and a mother who was overworked. So even though I was in a very privileged situation with a husband and help in a household where I can talk to him. a man about a thing like this in a forthright way, that I had gone on.

I mean, this was 19, by now 68, 70, thereabouts. I was married for, at that point in 1970, for seven years. I mean, I was the kind of person who would run home from work at lunchtime to bake a bread, to make bread crumbs, to put in the turkey. And then I'd go back to work. I was obsessed with being a good homemaker.

We had to do it all. Of course, no one can do it all, but that was the first kind of proof text for feminism can work, you just balance your life a little better, and of course you make yourself crazy, and you never get enough sleep, and you're tense, and you're anxious. He might have gone to the supermarket, but you made the list.

Because you've got in your head all the things that needed to be done. The trick is to get it into his head, or her head, whoever your partner is. Worrying about things is divided. That comes before acting, is that you have to worry about, hey, we're out of milk, we're out of butter. You have to worry about all the little things of family life, and not just go with the list that your female partner came up with.

Helga: And so, you were doing all this work. You had these three kids. And so what did that do to your relationship with them, and how did you navigate the challenges?

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: I would have answered this question very differently before I wrote my most current book, called Shonda: A Memoir of Shame and Secrecy, in which I admit My real shame at not ever making it safe or comfortable for my children to object.

In other words, I was trying so hard to do it all and do it right, and they're very smart kids, and they noticed how hard I'm coming home, I'm giving them quality time, I'm halfway in the kitchen making dinner, and I'm also on the floor building Legos with them, and I'm on the phone making a Parent teacher meeting, and they picked it up, so they were not going to say, Mom, we're not getting enough of you.

But when I was writing this book, I had a conversation with them, and I said, I'm feeling in retrospect that I may not have given you enough mothering. And out it came. Well, Mom, it's okay. You were saving women, you know. You were out there in the world, and you've made the world a better place for us, my daughters would say.

I have two daughters now, 58 years old, and a son who's 55, and you know them all from childhood, which I just think is so great that you actually are talking to me about a life you witnessed a little tiny bit of. And so they had a conversation with me, saying We could have used more of you and said, well, why didn't you tell me?

Why didn't you object? Because we really felt you were so invested in this movement. It would be crushing to you. And I started crying. I felt so awful. But, you know, I can't fix it. The worst thing in the world is what you can't fix. All you can do is go back and say, I'm really sorry. I'm sorry I didn't make space for you.

I should have said, how's it going? Are you getting enough parenting from both of us? Even though Bert, my husband, knew more about these children than most men do in a lifetime about their kids. He knew the names and phone numbers of their friends. Not a whole lot of men did. By the time we created a feminist household, I went away for six weeks to finish a book.

I went to an artist colony in New Hampshire a couple of times. And he ran the house, the children, the lists, the family, the, the, the doctor's appointments, all of that. But I never stopped and asked them, are you getting enough from me? And we can't do it all. Women get so frazzled because they think everyone else is doing it and they're failing at it.

Nobody's doing it. Well, because it can't be done. It's two jobs. It's two separate jobs. Even if you split it, it's not ideal. The kids came out okay. Helga, you have to admit that. They're functioning.

Helga: We'll get to that. Tell me then about how you integrated Your religion into your activism.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Well, you're very good, because the whole interview is basically matching the chronology of my life.

And there was a moment when I felt I had to link up my Judaism with my feminism, and that was really hard. Judaism, like every other religion, is a patriarchal space, it's a patriarchal structure, framework, any way you want to put it. And women's role in it was secondary, and I happen to have been very well educated for a girl in my tradition.

I have some decent Hebrew, I can understand it. I certainly understand the prayer book. I know what I'm saying. And I was educated but couldn't do. Educated but not authorized to do. And to be so impotent when you have feelings for your faith and your traditions. You know, faith and traditions for me are separate things.

You don't have to believe in God to want to light Hanukkah candles and give your kids a feeling of celebration for the survival of the Jews way back when. And the survival of the Jews over the centuries has become pretty much an obsession of mine, especially right now. So for me, I had to interrogate feminism with an eye to how most women are treating Jewish women.

Seeing Jewish women, stereotyping Jewish women, and I had to critique that as a writer and as a theorist of feminism in those early years. And then the same thing happened in Judaism. I had to say, I love this tradition, but look at how women aren't on the Bema, up on the platform. Women aren't reading the Torah, our Bible scroll.

Women aren't given or taking leadership roles in our organizations. Even the women's organizations very often were headed by men in various cases. It's like Ladies Home Journal is edited. by a man. Two men, actually, until, uh, early 70s. Imagine that. Good Housekeeping was edited by a man. Seventeen Magazine was edited by a man.

You can't imagine that, so why would I be surprised that Jewish organizations were run by men? So an entire parallel revolution of rising feminist consciousness caught up with the secular feminist movement in the early 70s. The secular, what we call second wave feminism, the first wave was suffrage, getting the vote.

The second wave was what started in the 60s. And I was late to the party, but I was there by 69, 70. And Judaism took a while longer to confront. And women rabbis didn't exist. The first woman rabbi was ordained in Reform Judaism in the 70s, in Conservative Judaism in 1985. In Orthodoxy they're not being ordained, they're being educated, same as I was, like, in my childhood.

But they can't be called rabbis. So, at a certain point, I wrote a book called Deborah Golda and Me, Being Female and Jewish in America, and it was published in 1991, and it did exactly what I just described. It attempted to reconcile Judaism and feminism. It can't be done in certain parts of Orthodox Judaism until the rabbis and the scholars catch up with the fact that when we talk about justice, justice, justice, shalt thou pursue, is a banner line for what all of Judaism is about, and we don't apply it to women.

It's not applied to women. It's plain and simple. So to arouse Awareness and anger. Anger is a good thing. Anger is a change maker. Anger nourishes when it comes to confronting authority. You need your anger or you'll get shot down.

Helga: But you agree that we don't all get to express our anger.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: We don't. We certainly don't.Oh, yeah. I mean, angry black women are scary, really scary to people and it can be passion.

Helga: I think a lot of times the things that I am passionate about, I can be loud and I stand up and I take up space and this is viewed by

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: many people as a threat. Yeah. As if it's a zero sum game, humanity and dignity, as if it's somehow or other me demanding mine or you demanding your dignity is necessarily going to take it away from men.

And that's because people in power are used to it and they really fight hard to keep it. Or from other white women, lady. Well, I'm sure. I'm sure. I was in a black Jewish, uh, dialogue group, a very intense one. We met once a month for ten years, and I'm not -

Helga: Do you remember who the black women were in that group?

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Well, Bernice Powell, did you ever know her?

She was, uh Head of United Church of Christ at some point, Marguerite Ross Barnett, who was the provost of CUNY, Harriet Michelle, who was the head of the Urban League. We met because in 1984, when Jesse Jackson was running for president, He used the word Hymetown to describe New York City.

Hymetown is a really pejorative way of saying Jews run New York. You know, or Jews run whatever it is. I think John Lindsay was mayor. I mean, I think people who weren't Jewish were all around, and yet he called it Hymetown. So it was very offensive. And then a very wealthy member of, uh, a Jewish organization ran a full page ad in the New York Times saying something like, Jews have to be crazy to vote for Jesse Jackson.

And David Dinkins and a bunch of white big shots, they got together and they made a big shot black Jewish group. It was about, 50 people, 25 from each community, and, uh, we met in somebody's boardroom, and I happened to be invited to be one of them, I think, because of something I had done with, uh, Or many things you may have done.

Something I had, somebody I'd marched with them, or something. And they invited me to be part of it. And at some point, the men in the group were what we call masculine posturing, and that's things like, when I marched with King, or when A. Philip Randolph and I chose to do such and such, people white and black were doing that.

And I rolled my eyes and caught the eye of Harriet Michelle, who was at that point president of the Urban League, an African American, very statuesque, you couldn't miss her, and she's rolling her eyes, I'm rolling mine, and after that meeting, I went up to her and said, if you were feeling what I was feeling about what the men were doing, let's start a women's group, and she said, I'm with you, sister, and then we thought, well, anger around Jesse Jackson's Hymetown and this man's ad, Jews Have to Be Crazy, was such that we could maybe be vituperative to the point where we need a moderator.

Harriet and I decided that the moderator should be Donna Shalala, who was neither black nor Jewish but could pass for both. And we thought, She is very good at dealing with strife and she'll be our moderator. And what was the importance of, 'cause we didn't wanna have the, of that kind of identity. We, we did, well, we wanted it to be black Jewish group, but we didn't want the person to be black or Jewish because we wanted somebody who would not have any.

knee jerk kind of gut reaction to any of the anger that might be stirred. In any case, Donna, it was just terrific because she just organized the first discussion in a way where we could put out the issues without personalizing and immediately, you know, that ad was, you know, It's the most horrible thing I ever saw, or I can never forgive him for Hymetown.

In other words, we did not want to start out that way. We wanted to build an agenda and get to all the issues, but find a way out of them, you know. Jesse said, I didn't realize the power of that word. He apologized. And we, who were in this group, thought it was a shonda, you know, a shame that Jews would do that, would say, you have to be crazy.

There's everything to look at that Jesse Jackson stood for. Why would you have to be crazy to vote for Jesse Jackson because of one word, you know?

Helga: Well, because you don't want him to be President of the United States, is one answer to that, too.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Yeah, of course. Of course, you're right. In any case, that was the genesis, and that was how we entered it, wanting to be careful not to offend, because we wanted to build trust.

And we didn't need Donna. And after the second meeting, she said, I'm out of here, you guys are fine, you know. And then we would talk. I'll tell you the moment that stayed with me forever. I mean, because for 10 years, I have so many moments. But the one that I think of very often, because it applies all too often. The Central Park jogger case happened while we were meeting. There were two I’ll tell you about.

And by this time, we had been meeting for a while, and we have a lot of trust, and one of our members, a Jewish member, comes in and says, Can you believe what those animals did? And the African American woman in the room shut down right away. I'm sorry to bang the table, but shut it down and said, Don't you dare call our children animals.

And the Jewish woman said, how can you defend that? And The African American women, each in her way, said, how can you believe that? How can you believe the cops? Well, I mean, there's this report. You know, there's this report of what they did. It was this, it was that. And the African American women said, If we believed every police report, And they went on and on, and it had never occurred to us to question the cops.

Why? So back in 1984 or 5 or 6, we are suddenly realizing, we trust the cops, and they don't. It was a huge idea. Why do we trust the cops? Because we're white. And when we call the cops, they come and they help us. They come in and they don't immediately start banging people around and shoving people up against the wall and suspecting that a pen is a gun.

And all that, you may say, how could you have been so naive? Because that's a class as well as a race thing. Because we never experienced cops roughing up us or our kids. And so that every time anything happens of any kind of nature having to do with violence and involving Black children, I'm immediately not believing.

I do not believe the cops. My first, my, my first is disbelief. So I changed the way I saw the world through the eyes of my African American sisters. The second time that happened was when Jerry Ferraro was running for, um, Office on with Mondale. 1988, was that, I don't know what year. The point is, the night we were meeting was the night that she gave her big speech and the Jewish women come in bouncing for joy.

A woman we say when she's Italian, but way we see a woman and. Our African American sisters said don't expect us to rejoice until there's a black woman or even a black man because a woman isn't so hard. Every white person has a woman somewhere in their life. The point is, is this country ever going to be ready?

And that was back then. And I realized I was reacting just as a woman. So the wonder of dialogue, and I've been in Jewish Palestinian dialogue and had the same experiences, is that what you think is so obvious gets really questioned at a deep level, and you have to say, I need to see the world through a broader vision.

I can't just look at the world as a white woman, and certainly not as a white woman of a privileged class, because I'm missing the reality.

Helga: You're listening to Helga. We'll rejoin the conversation in just a moment.

Avery Willis-Hoffman: The Brown Arts Institute at Brown University is a university wide research enterprise and catalyst for the arts at Brown that creates new work and supports, amplifies, and adds new dimensions to the creative practices of Brown's arts departments, faculty, students, and surrounding communities.

Visit arts.brown.edu to learn more about our upcoming programming and to sign up for our mailing list.

Helga: And now, let's rejoin my conversation with author and activist, Letty Cottin Pogrebin.

Helga:What do you think of the state of women's issues, women's liberation, feminism, now, in all its forms?

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Well, I'm very angry at my feminist sisters because they have not spoken out about what Hamas did to Jewish women.

Helga: Mm hmm.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Because I've been Almost 40 years writing about and marching for and lobbying for Palestinian rights, asking this government to interfere and to advance peace and to pay attention to the way that Israel and especially its right wing governments have treated and other people. And for there to be no No empathy, no shock, no horror, no me too type rage when women were cut up, sliced up.

Their genitals, their breasts, this was misogyny. It wasn't, quote, just terror shooting and scaring and kidnapping men and women. It was targeting women for a particular kind of torture. And not to hear from the women's movement, because it happened to Jews, has really left me kind of paralyzed with sorrow and shame.

If you look at the charter of Hamas, Hamas is a totally misogynistic movement. It wants women in veils and covered and you can get your hands chopped off at the wrist for showing a piece of flesh. And this is who they're supporting. Who, because they're afraid not to criticize anything in the Palestinian cause, is mystifying to me because we've spent decades differentiating between Palestinian groups that do terror and Palestinian groups that want their rights.

Period. Want justice? And we've made, we, when I say myself, I count myself a liberal Zionist, I count myself a progressive. So, how I feel about feminism at this moment is very particularized, Helga. I always, Kind of create an image for my own activism that is a seesaw. And when women are under attack, that's what I'm going to look at.

And when Jews are under attack, I'm going to slip the other way, and that's going to be my priority. And that's where I am right now. I'm feeling threatened as a Jew. I'm feeling personally imperiled and endangered by the new anti Semitism and feminism has had very little to say about it. And I've spent, you know, 50 years of my life working for women's rights and that hurts because somehow other Jewish women's bodies don't seem to count.

Helga: And black bodies don't count either. I know you know this. It just feels so important for me, in this moment in particular, to keep saying it. Yeah. Because when I watch the news, what gets established over and over and over again is that slavery was not the worst thing. The enslavement of black people was not the worst thing in the world, but that this was.

It's not to separate us, but then what happens. What I feel that is being said is, yeah, that happened, but now, let's move on. Yeah. If someone would say, let's move on, That would at least keep me clear about what's happening.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Yeah. Can I say something about what you just said? Absolutely. I have really had it with the competition of tears.

I call it that. As if we don't have enough tears for the Holocaust and slavery. Look at what has happened with the 1619 Project. How people have tried to shut it down, keep it out of schools. Nobody wants anyone to know what America did. Yeah, I mean, but does that mean that you have to rank the slavery versus the holocaust?

Not, not to me, you don't have to rank any. And Hamas, I put in that category. Put that in that category, because it was so, it was so brutal and savage. And then somebody said, how dare you say savage? I said, because cutting off breasts and mutilating genitals. Is not normal warfare. I would understand if Hamas came through the fence with their rifles and shot everybody they saw on the Israeli side.

I get it. Because of the way Israel has treated Palestinians. I would get it. Everyone equally gets shot. When you take women out and you, and you torture them, you're killing them. You're in the category of slavery in the Holocaust.

Helga: Okay, and I, I understand what you're saying about this competition of tears, but if you separate families, if you sell children, if there is convict leasing, if there are, right now, prisons in which the majority of prisoners are African American.

I don't understand how we don't talk about that in the same breath that we speak about the Holocaust, that we, that we speak about any atrocity.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin:You know why?

Helga: Why?

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: And I know why. Because that happened here. And, you know, the Holocaust, something happened over there, other people did it, it's not, you know, it's not our fault.

So, what's the significance of it happening here? Because people cannot stand thinking that they have anything to do with that. Why else are they picking on this New York Times series with such fury? Why else are they Fighting to get a false narrative into the educational system about what happened to African Americans in this country.

Because they don't want to feel lousy, worse than lousy, about themselves. They want a pristine, everybody can make it here, look at Ralph Bunch. How many times have I heard, look at Ralph Bunch, when I was growing up? Or look at Oprah. They'll take one remarkable, triumphant career and say anybody can make it here.

Well, I mean, it's absurd, but people would have to take responsibility, as this is our heritage. White people did this, even if your people weren't here, and you have benefited. That, that's what I always say to Jewish people. We weren't here. We didn't do this, you know, mostly. There were some Jewish slaveholders in the South, as there were of every possible kind.

But you can't say it's not our responsibility. Jews want to opt out of responsibility. The way we do it is, I wasn't here. You know, and the way other people do it is, get this stuff out of the curriculum. I think when you realize what it would be for, for full responsibility and reparations which I happen to be in favor of, when you realize what kind of acknowledgement that would be, it's so huge, I, I don't think -

Helga: And what people would have to give up.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin:Exactly. And no one is willing to give anything up. And so it's easier to just not speak its name.

Helga:Yeah, right.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin:Yeah, power is never given, it has to be taken.

Helga:But Letty, not if I'm gonna get shot in the street.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: We'll think of how many people. Got shot or got trampled or got -

Helga: I'm not disagreeing with that. I'm talking about my ability to take power.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Yeah, you can't take power if you're powerless for too long.

Helga: And I don't, I don't feel powerless, but I don't feel that it is safe for me to insist that there be fair housing, that I go to a protest march. You know, I left a protest march, a George Floyd protest march here in New York, and the people had gathered and they were walking across the Brooklyn Bridge.

And I left, and Because you felt unsafe? No, because I was about to leave the country, and I didn't want anyone to arrest me for there to be some record of my being arrested, and then have my ability to go out in the world and make my contribution, to make my work possible. And so I left.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: That's a very -

Helga: I took my body out of that situation so that I wouldn't pay for it somewhere else.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: You had to calibrate it that way.

Helga: Yeah.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Because it was too much to give up.

Helga: I didn't feel good about that, though.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: No, I understand.

Helga: And I'm not interested in only just saving myself.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: But it's terrible to be forced into that calculation. They have you and they squeeze.

Your presence is what creates solidarity and numbers and so that kind of punitive sword hanging over your head probably stops a lot of people. I mean, there are people who go to get arrested. I know a lot of Jews, a lot of rabbis, have gone to George Floyd's things to get arrested, to make a point. But if you can't afford it in your career to get that on your record, that's like

Helga: But it's not, I'm not talking about my career. I'm really talking about my ability to make my contribution to my community and to my nation, and I feel a civic responsibility to do that work.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Right, but you're hobbled by this consideration that you have to have rolling in your head simultaneously.

Helga: Okay, but then I want to know who's going to take my place and walk across that bridge.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Because maybe somebody who feels that is their contribution. I remember when one of the women's marches, when old women said, put us in the front. Because maybe then they won't trample us.

Helga: And during the Civil Rights Movement, they put the, put the white people in the front. That's it.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: So there are those for whom that is a mission. This is complicated, but simple.

Helga: How is it simple?

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: It's simple because of the way you just said it. It's simple because there's this trade off that's being forced on you to consider whether it's going to impede your ability to contribute to your society because of the hazard of being in that group of marchers.

Helga: And I'm saying that It doesn't hobble me if I know that someone with a different thing to lose, or nothing to lose, or less to lose, will take my place in that march.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Yeah. And I'm raising the old women, you know, or the white people who were willing to be in the front. And, and thank God for them. I, you know, I marvel, I marvel at the people who were really ready to be manhandled in the worst way and have their heads bashed in.

When you look at the Pettis Bridge pictures, I mean, I couldn't do that. It has to be somebody else who could make that point and create that visual, which is a wake up call for people of conscience. How many people of conscience are left, I don't know.

Helga: I want to talk about the circumstance of our reconnection. I was hosting a program and leading a conversation and you and Bert were sitting in the front row because you were very close to me and I remember looking over and seeing your eyes and thinking, wow who is that? Because I wasn't sure. But I felt that you were there and that you were rooting for me, that you were rooting for this conversation and that you also had some connection to the performance and to that music. Talk a little bit about the concert.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: I have chills from the way you described it. I remember that evening so vividly. I don't recognize you, but I am so drawn to you that I'm like staring at you more than I'm staring at the singer. And I'm marveling and I'm thinking to myself, why, why am I nodding and why am I like, I'm trying to get to you with my spirit to tell you I know what you're doing, Helga.

I didn't know you were Helga. I identify with you as a woman trying to get a man to say something meaningful, and is simply talking about, oh yes, that cantata, and that, you know, aria, and that, you know, and he's talking about a city where he's saying, or the name of this and why it means something, and he doesn't say one thing in response to your questions.

which were probing the human element. How do you feel when you sing this? You were asking, I forget what, but they were great questions, as I see you're a pretty skilled interviewer, and he was like a blank slate, and I'm so I'm nodding like I'm hoping that you'll keep at it, and so at the end I start Roaring, and I do a standing ovation, and I hear others stand up.

And then I start moving toward you because I want to tell you all this, that I felt this about what you were doing. And your face got an expression of horror on it. Like a, like a comic book, and I turn to look at what you're seeing, and my husband is on the floor. My husband has Parkinson's, and he forgot that he can't walk, except with a walker, and he fell over.

And he ripped up his ear, and it turns out he broke three ribs, and he did everything terrible. And you, Came running up to me because I immediately said it's my fault. I never should have gotten up I never should have turned around and I'm saying all this to myself and you grab me and hug me and say it's okay It's okay.

It's not your fault. It's not your fault and you help get him up and we walk to the back of the place and you help me centered and you help me call 9 1 1 and you stay with me. Oh, first you organize the room, which by the way is, is a great thing to watch. Everyone will stay in their seats please and your mellifluous voice and if you wouldn't mind musicians, if you would continue to play.

The singer's gone, he's out of there, but the musicians play while you help. Me and my husband, totter and teeter to the back of the room, up the aisle, keeping everyone in their seats. What you did was such an act of support and feeling and loving kindness. You didn't know at that time who I was. I may have been vaguely familiar, but you see a lot of people.

And so only when we got to the back together and then people were allowed to go and leave and you're staying and you're helping and you're holding me And I ask you your name. No, you see What I'm writing on my phone, you see the word Robin Pogrebin because of my three children she was the only one in New York City and you see the word Robin Pogrebin and I'm calling her and you say You're Letty.

You're Letty. I'm Helga, because you had not introduced yourself by name up there, and you know, I don't know a lot of Helgas I would have put two and two together, but you say, I'm Helga, and I went, oh my God, and here you are, an angel to me. You were being an angel to me, and you stayed, and then Robin came, and went to the emergency room, and I I just felt how I would have gotten through that by myself, I don't know, because I was so into self blaming that I had gotten into my own head that I was going to go and talk to you, and I was going to have this feminist, you know, understanding moment, like I see what you were doing with this, with recalcitrant guy.

And you switched effortlessly into the personal. You switched gears the way. Good human being does when a situation demands switching. And you was not the cool narrator up there anymore. You became, without knowing me, and then you find out I'm the mother of your friend from high school. And, uh, so that's why, Helga, it was, um, you really hold a place in my heart.

My husband's had a lot of falls since, and I've had a lot of them alone. And I know the difference. Seriously.

Helga: Don't make me cry on podcasts. It's not allowed. People make me cry all the time, so you don't get off the hook either. What I want to say to you, and I think I said it to Robin, in her email to me is that I'm glad it was me.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: I'm so glad.

Helga: I'm glad I was there. And there was this complete moment of humor where after I said, I'm Helga, and you said, Helga?

I said, Letty? Helga? Letty? Helga? Letty? And also this whole thing flashed in my head also, and in my body of not only being in high school with Abby and Robin, but being in your home and being welcomed there and feeling not other and not strange.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: I'm so glad to hear you say that.

Helga: But that I could be raised by many women.

I could be mothered and have been mothered by many women.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: And then you mothered me right back.

Helga: It's my honor. Thank you, Letty.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Thank you, Helga. Thank you. We're joined at the heart from now till eternity.

Helga: We are joined at the heart. I want to, uh, last thing is to ask you if there's a thing that you do every day that would help a person listening along their path.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: I'm a gratitude lover. I try to immerse myself in gratitude and what I have rather than what I don't have. And I've led a very charmed life. I have to knock wood here because I'm superstitious. I have had a blissful marriage. I have wonderful children and grandchildren and I've had work that means something to me for more than 50 years.

Now I am Watching my husband depleted, and it's really hard to wake up every day and focus on what I have and not what I don't, or what he has and what he's losing. But it's something. It's a practice. Has helped me get through this time, and I'm sure there are a lot of people listening who have Sadness, sorrow, suffering in their life or in the life of someone they love And it's very hard to focus on what you're grateful for in the midst of That's suffering, but you also have that something to be grateful for.

And you have to kind of redirect your head to that just to get into the day. Thank you.

Helga: This has just been amazing to sit with you.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: Thank you And the same here.

Helga: Thank you.

Helga: That was my conversation with Lettie Cottin Pogrebin. I'm Helga Davis. Join me next week for my conversation with the host of the New York Times Modern Love podcast, Anna Martin.

Anna Martin: I never anticipated in my professional life I would be using the word love in so many emails and conversations and pitch meetings and prep sessions with the team, but I'm writing sentences like, I love your love and I'd love to explore your love.

Helga: To connect with the show, drop us a line at helga at wnyc.

org. We'll send you a link to our show page with every episode of this and past seasons, transcripts of my conversations, and resources for all the artists, authors, and musicians who have come up in conversation. And if you want to support the show, please leave us a comment and rating on any of your favorite podcast platforms.

And now for the coda. Would you give us one prayer that feels important to you and feels important to this time?

Letty Cottin Pogrebin: It's called the Shehecheyanu. It's a hard word to say. and we sing it. I'll do it. It takes 10 seconds. Baruch atah adonai Eloheinu, Melech ha olam, Shechecheyanu v'kiamanu, V'higiyanu lazman hazeh, Ah, ah, ah, ah, ah, Ah, ah, ah, ah, Ah, ah, ah, ah, Ah, ah, ah, ah.

And it means, thank you, God for keeping me alive and allowing me to live to see this moment. So I'm reciting it here for this moment that you and I have had. It's supposed to be said at the beginning of holidays. Or when you eat the first fruit of the season, the first peach after a winter.

Those are the days when you didn't get peaches from, I don't know, Hawaii. It's supposed to stop time and allow you to notice. We call it mindfulness now, but then it's just the shehecheyanu. You stop time and you bless the one, whoever you believe, that allowed you to be alive long eno ugh to see this moment.

So, here I am, sitting across from you, and we're looking at this long arc, maybe, the last time we saw each other, you were maybe 15, until that night, and here we are talking about all these things that have mattered to both of us, together. I'm glad I lived to see this moment. Me too. Thank you. No making the host cry.

Helga: Since recording this episode, we learned of the passing of Lettie's husband, Bert. Lettie's conversation includes beautiful memories and stories of their life together, his importance in her activism, and his role in reuniting the three of us in 2023. We here at Helga send our condolences to you, Lettie, and your family.

Helga: Season 6 of Helga is a co production of WNYC Studios and the Brown Arts Institute at Brown University. The show is produced by Alex Ambrose and David Norville, with help from Rachel Arewa, and recorded by Bill Sigmund at Digital Island Studios in New York. Our technical director is Sapir Rosenblatt, and our executive producer is Elizabeth Nonamaker.

Original music by Michel Ndeghe Ocello and Jason Moran. Avery Willis Hoffman is our executive producer at the Brown Arts Institute, along with producing director Jessica Wasilewski. WQXR's chief content officer is Ed Yim.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.