Only the Good Die Young: Verdi's La Traviata

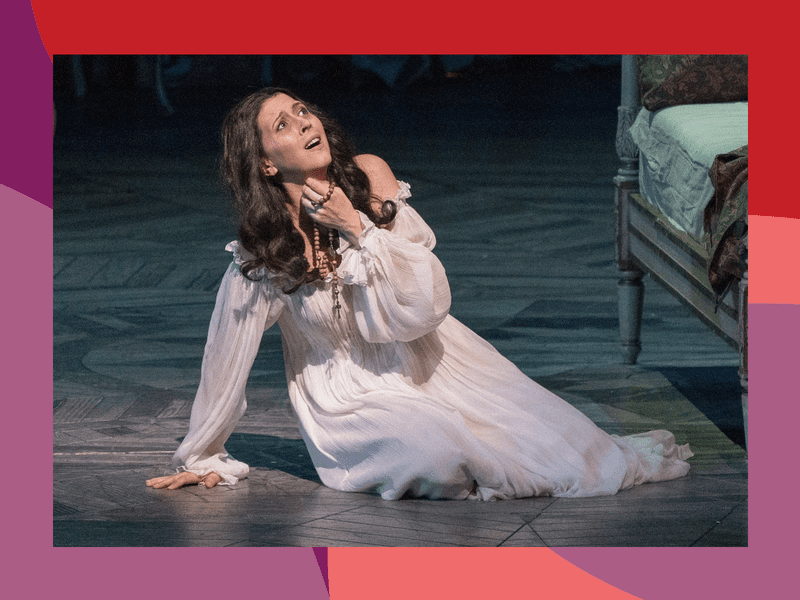

( Richard Termine / Met Opera )

Aria Code S3 Ep 10

“Addio del passato”

from Verdi’s La Traviata

BILLBOARD

Theme music

OROPESA: “Please don’t let me die. I don’t want to die, I want to live.” And you can also, at the exact same time say - “I am ready to die.” That living conflict is exactly what life is!

GIDDENS: From WQXR and the Metropolitan Opera, this is Aria Code. I'm Rhiannon Giddens.

SCHILLINGER: It’s about a unique mind, a unique sensibility, a unique heart that has been buffeted by the realities of her time and by that terrible illness.

GIDDENS: Every episode, we pull back the curtain on a single aria to see what’s behind the scenes. Today, it’s “Addio del passato” from La Traviata by Giuseppe Verdi.

TURTURRO: I think great music, and music that has lasted, is a sort of emotional transportation. It’s almost close to a form of prayer.

GIDDENS INTRO

Here on Aria Code, we’re always talking about the story, and how it connects to the world the opera was written in and the world we live in today. Sometimes, though, the story isn’t just a story -- there’s a real person in there, who lived and died and had a life worthy of an opera.

The person behind today’s opera was real. Her name was Marie Duplessis, and she was a courtesan living in Paris in the middle of the 1800s.

She was incredibly successful, sought-after. She had no trouble paying her own way. But her independent life didn’t last long. Marie died of tuberculosis when she was 23.

One of her lovers was so inspired by her life that he decided to commit her story to paper.

His name was Alexandre Dumas fils -- “fils” meaning “son,” because he was the son of the more famous Alexandre Dumas. Now dad wrote The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo. But the son - the son titled his book La Dame aux Camelias -- The Lady of the Camellias -- which he later turned into a play.

And that’s where Giuseppe Verdi comes in -- literally. He comes into the theater, sees the play and is immediately inspired to compose La Traviata.

Verdi saw something special in the beauty and mystique of the young Marie Duplessis, and he immortalized her as the character Violetta Valéry. She is La Traviata - the fallen woman.

Now Violetta has a lot of showstoppers throughout the opera, but today’s aria is a quiet and intimate goodbye. She sings “Addio del passato” -- a farewell to the past -- while she’s on her deathbed. She’s reflecting on everything she’s sacrificed during her short life, and what that all means for her as she dies.

Now I’m not exaggerating to say that La Traviata is one of the greatest operas ever, certainly one of my top favorites. But what exactly was so special about this Lady of the Camellias? Why did so many men love her and want to tell her deeply human story, even at a time when women -- and especially courtesans -- weren’t treated with a whole lot of dignity? We have four guests to help us figure it out.

---

FIrst, soprano Lisette Oropesa, who follows in her mother’s footsteps every time she walks on stage as Violetta.

OROPESA: Traviata was her role. And I remember being a young child to see her performance of it and seeing her die on stage and being miserable and feeling like, man, that opera is really tragic!

Next, actor and director John Turturro, who also has a childhood connection to Verdi.

TURTURRO: I have this album -- my father and my uncles used to listen to it, and it’s 40 tenors singing “Di quella pira” from Il Trovatore. And they used to analyze all the different tenors -- who cracked, who couldn’t hold the high C. It would be sort of like Aria Code, but with all these men around this record player, and it was hilarious… hilarious.

Fred Plotkin is here! He’s the author of Opera 101: A Complete Guide to Learning and Loving Opera.

PLOTKIN: Verdi is my hero because he represents all the greatness that an artist can achieve not only artistically but as a human being. His heart was so big, on his grave, it says that he wept and loved for all of us.

And finally, Liesl Schillinger, a writer and journalist. A few years ago, she made a new translation of Dumas’ novel, The Lady of the Camellias.

SCHILLINGER: I wanted to knock off any of the antique armatures that would make people not understand how relevant this is to the world we live in today.

Let’s dive into the story of this Lady of the Camellias -- both the real-life woman and Verdi’s famous heroine from La Traviata.

DECODE

Marie Duplessis

SCHILLINGER: The Lady of the Camellias began her life as a peasant girl from Normandy with a violent and abusive father. But she came to Paris when she was about 14 and she quickly changed her name to Marie Duplessis. Practically, overnight she managed to become the talk of Paris.

You know, her comings and goings were published in the newspapers and the gossip sheets. This woman was slender and she had magnetic, big black eyes and fair, fair skin. People wrote that she looked like a little doll. Her apartment was sumptuously decorated And, she really had quite regal surroundings.

We might all hear about Cardi B, or Kim Kardashian, or about Paris Hilton. She kind of had that degree of notoriety. And socially ambitious men wanted to have the allure, the special glow of being chosen by her.

She was taken on by some of the most influential, rich, and cultured men of Paris. She rubbed elbows and more with counts and Dukes and editors and playwrights and poets.

PLOTKIN: Violetta Valéry is 23 and is what used to be called a courtesan.

OROPESA: And that is essentially selling her body to rich men. In that time being a courtesan was one of the only choices a young lady might've had. If she didn't get married.

TURTURRO: Besides being a nun, you know?

OROPESA: She's an unequal in the society that she's in. She wouldn't have any freedom unless she did this.

TURTURRO: She's a very smart, clever woman who’s a perpetual outsider.

PLOTKIN: She is also cultured and kinder than anyone else around her. But she's naive to the ways of human cruelty and selfishness, and this is part of her undoing.

SCHILLINGER: She thirsted for the cultured fun and spectacle of Paris in the 1840s. And she went out every night to the theater or to the opera or to the ballet. And she cut a particularly fine and noticeable figure when she would show up in her theater boxes. She wore a very simple, but tasteful dress. And what was most distinctive about her were the fine jewels she wore in her simple hair and on her bosom. But also the fact that she would wear camellias, these beautiful, smooth flowers, which were very exotic and hard to get. She would wear white camellias, I think twenty-five days out of the month and then red Camellia's, five days of the month and everyone pretended they didn't know why.

So poetically people began to refer to her as “The Lady of the Camellias,” La dame aux camélias.

La Traviata - Beginning

OROPESA: So the opera opens at a party. And Violetta is kind of the lady of the evening. Serving drinks, entertaining her guests, talking with everyone. And we find out that she's ill.

PLOTKIN: We know already at the start of the opera that she's coughing and she will meet a bad end due to consumption to tuberculosis.

OROPESA: And there's this young gentleman at this party who wants to meet her, Alfredo. And she meets him, kind of writes him off.

PLOTKIN: She says that she's always free and she will never form romantic attachments to anyone.

OROPESA: As she says to Alfredo in the first act, “I wrote that off a long time ago. I don't do love, I do transactions,”

TURTURRO: Her whole relationship with Alfredo, she wants it to be a transaction. And so much of relationships, you know, are transactions and the whole idea of marriage, for example, if you go back to Roman time [sic], it was a business transaction. And it still is in some ways, you know, for lots of people.

You know, he's going to take care of her or she's going to take care of him. And plenty of people have that. They don't have the basic connection or really enjoyment of each other's minds or spirits, you know, and that's really rare.

PLOTKIN: But she likes Alfredo. And he definitely likes her. And they quickly fall in love.

TURTURRO: She opens herself up to this guy who's from a different world.

SCHILLINGER: Her love for this man was strong enough to make her say, “Alright, I'm going to quit running this dynamo, I'm going to give all for love.”

Only society won't let her do it.

All of us are familiar with the story of hookers with hearts of gold, of the fallen woman. But that's not really what the story of the Lady of The Camellias is about. It's about a unique mind, a unique sensibility, a unique heart that has been buffeted by the realities of her time. And by that terrible illness.

PLOTKIN: They move to the country. They decorate very quickly, this only can happen in opera. And all seems good until the father of Alfredo shows up.

OROPESA: They have a huge confrontation because Alfredo's father comes in and basically tells her, “You need to leave my son right now, because I'll be damned if he's gonna leave his inheritance to you and spend his inheritance for you, you are nothing but the downfall of my family.”

PLOTKIN: “And my daughter is about to be married and you would disgrace my daughter.”

OROPESA: And he just says every possible thing he could say to break her heart. And finally she gives in and says, “Okay, I'll leave him.”

SCHILLINGER: The book was very much written to make society look at the many-sidedness of the women they condemned too easily.

TURTURRO: It says a lot, you know, about society. I keep thinking of, like, a piece of meat that needs to be tenderized. You need to tenderize the meat of humanity, because if you don't do it, it's a tribal impulse that people have.

La Traviata - Act III

PLOTKIN: The last act of La Traviata begins with the music we heard at the beginning of the opera, a very sad prelude that sets a scene of darkness. It's Paris in February, and therefore there's very little light. It's very cold. In Violetta's room typically, whatever works of art she had, her jewelry, her furniture, are all gone, and there's just a bed. We know that for Violetta, this is it.

OROPESA: She is being visited by the doctor who tells her she's going to be fine. And of course she knows that that's not true.

PLOTKIN: And he takes your hand. And he says “Addio.” And then he quickly corrects himself. “Addio, a piu tardi,” in other words, “Farewell... until I see you later.” Because “addio” is the final farewell. And while he understands that he won't see her again, he has made a mistake in communicating to her that this is it, that she's going to die. And she says, “Non mi scordate,” “don't forget me.”

SCHILLINGER: She wanted to be remembered. She was aware, I guess, of the effect she had had in life and wanted it to continue.

TURTURRO: It's a universal impulse, but it's in a heightened situation, because she's got limited time.

PLOTKIN: The doctor stands up and walks to the door.

OROPESA: And he tells the servant, “She's going to be dead within a few hours.”

PLOTKIN: And then suddenly the music wells up again.

OROPESA: And Violetta goes through her letters and she has this one letter in particular that she has clung to as the element of hope, which is a letter actually from Alfredo’s father.

PLOTKIN: And the letter says, in effect, “You have kept your promise about not marrying Alfredo and I told him, myself, says his father of your sacrifice, and he's going to come back.”

OROPESA: Alfredo is going to rush back to Violetta's side, and everything's going to be alright. And I think in her heart deep down, she thinks that she won't make it to when he returns.

PLOTKIN: And there's a thud in the music as Violetta realizes it's too late. With this disease, all hope is dead.

SCHILLINGER: They didn't know how to cure tuberculosis in the mid 19th century. She just had hundreds of visits to the doctors in her last weeks of life. They gave her asses’ milk and purgatives, and they told her to lie on horse hair. They didn't know what to do. She simply could not be cured.

OROPESA: And she sings this beautiful, beautiful aria “Addio del passato bei giorni ridenti,” which means, “Goodbye to the beautiful days of laughter of the past.” You hear this beautiful oboe solo.

And the oboe has a very melancholy sound.

PLOTKIN: Well, if you think of the wind instruments in the orchestra, the flute tends to accompany joy, and we hear it in the first act when she's singing “Sempra libera,” and she's bubbly and so on. The oboe is sadder, is more plaintive. There's a mournful sound, a more muted sound to the oboe.

OROPESA: It takes air and it takes breath and that's what Violetta doesn't have. And you can hear the exhaustion. You can hear that when she puts her accents, [sings] they're on the second beat and not on the strong beat. It's like she doesn't have the strength to put them on the right beat. They're late.

And we go into six-eight time, this kind of waltzy time -- 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, and that's because, that's kind of been her world, the world of the dances and the balls and the parties.

PLOTKIN: Verdi was very precise in his instructions for singing this area and among the details come at the very start. He says, “dolente e piano,” “With pain,” “Addio,” “With pain,” “del passato,” “of the past.”

OROPESA: “Goodbye to all the beautiful dreams that used to make me laugh, the past times of joyful dreams and the roses of my cheeks are pale.

And the love that Alfredo gave me, I don't have, it's not here now.”

PLOTKIN: This is a song of memory, of a time when things were -- to use an old Parisian word - gay and joyous, and we used to dance and we used to waltz, but the waltz has been slowed down because everything for Violetta now is effortful.

OROPESA: And so it's kind of waltz with death in this final aria that she sings.

SCHILLINGER: What Marie said to her lady companion when she was dying was, “I want you to put a very weak bolt on my coffin.” And the pathos of that is heartrending in the book and brings you to tears of course at the opera, as you hear the weeping singing of the dying, consumptive heroine who’s been so self-sacrificing. The music’s nuance allows you to feel the shades of her mind and her heart.

TURTURRO: I think great music and music that has lasted is a sort of emotional transportation. It’s almost close to a form of, maybe prayer, and it never gets old for me. As I’m pushing this ball up a hill, I can put it on and I’m like, “Wow, gotta keep going. Gotta keep going.” It just pushes me forward, because it’s just beautiful.

OROPESA: So she's in a minor mode and then we suddenly go into a major mode that she brings. We're just in a major mode of the key that we've just heard, which was A minor. Now we're in A major. And for some reason, the major section is the place where she calls herself “Traviata” and Traviata means “person who is not on the journey,” “via” is a, is like a way or a road. And so “Tra via,” “off the road,” Traviata, she's a person who's not on the via that she's supposed to be on.

PLOTKIN: “Traviata” is a word that suggests a wayward woman, a forsaken woman.

OROPESA: She says, “Smile unto her desire. Forgive her and take her into your arms, O God.”

PLOTKIN: But then she says, “Or tutto, tutto finì,” “And now it’s all over.”

OROPESA: And she ends up this high note, this high A, and you hear like this kind of cry of pain that kind of is abruptly cut off. And the oboe takes over again and brings her back into the minor mode. So it's like she's trying to like fly up out of her earthly situation. And the oboe grabs her and brings her back down to earth into the minor mode again. This is what makes her a human being. “Yes. I don't want to die, please. Don't let me die. I don't want to die. I want to live.” And you could also at the exact same time, say “I am ready to die, but just please take me to heaven.” It’s like, “I've accepted it. Haven't accepted it.” That living conflict is exactly what life is.

SCHILLINGER: She writes letters to her lover while she is suffering and her last weeks of life and her hand is so weak because she is so feeble. In her letters. She writes of her suffering and she writes of her loneliness, but she also shows that even in the last weeks of her life, despite her fever, she couldn't resist going out, even when she's only a day or two from death. And she goes to the vaudeville where she let her young lover meet her for the first time. And she says that she spent the entire night with her eyes fixed on the stall he had occupied, just wishing she could see him. She's taken home half dead. She writes, “I coughed and spat blood all night today. I can no longer speak. I can hardly move my arms. My God, my God, I am going to die.”

OROPESA: There is an obvious case of deceptive simplicity spelled out in “Addio del passato,” the fact that it looks simple on paper, almost always is code for difficult. I mean, people who sing know that the fewer notes there are written down the harder it is to sing because you're more exposed. Your phrases are going to be longer and you have fewer notes to do something with. So you have to do more with every note. And that takes a lot of air. It takes a lot of strength. It takes a lot of musical give and take.

PLOTKIN: Verdi was always so economical. There were no extra notes in his operas because he moved the drama along. And he understood that if we in the audience had to suffer through beautiful music that did not serve the drama, then he was not doing his job. And that's what made him stand apart from any other composer.

TURTURRO: If you've done all the work beforehand there's nothing more eloquent than simplicity. And I think when you're a young performer, you think, “Okay, if I show it all, I give it all, that's the apex.” And then later on you start to realize, “No, I can be really simple, I think that's what you remember in life too; that graceful, generous gesture that someone gave to you at a certain moment. And you just were like, “Wow, that, I'll never forget that.”

Aria - Second Verse

OROPESA: And then she sings another verse, we have a pianissimo, “dolente e pianissimo,” written into the score and dolente means painful hurting, and pianissimo of course, very soft. And she says, “Joys and pains very soon will be over.” So, not only will I not be happy anymore, I will also not suffer anymore. The tomb is the end. It's where everybody ends up. We're all the same. We all end up in the same place.

PLOTKIN: “My grave will have neither tears nor flowers.”

OROPESA: And then she says, “Non lagrima o fiore avra la mia fossa,” which means “No tear or flower will have my pit,” “la fossa,” is like your pit where you're buried. So, like, the hole, the six feet in which you're a grave is placed. It will not have any tears and it will not have any flowers. “No cross with a name,” In other words, no tombstone that will cover this skeleton. “I'm going to be in there and I'm going to become no one. I won't even have a name, there won't be a cross that marks my grave,” because she won't have a Christian burial because she led the life of a courtesan.

TURTURRO: Well, courtesans couldn't be buried. And but that also goes along with actors, actors, we're not allowed to be buried. They were considered sort of scoundrels. They basically were thought of as courtesans and a lot of courtesans were actors. I kind of get it. The whole idea of it, the masquerading of it, the, you know, playing other people.

Believe me, I've done a lot of really stupid things that I'm not ashamed of because I have had to support my family and stuff, but that has nothing to do with who I am. When you come home and you say, “Well, you know what, I've got to take a lot of showers now. And I got to really kind of come back to who I am,” but, you know, it's, if you do too much of that, you don't come back so easily.

OROPESA: Once again, we go back into the major mode and she says, “God, please, you know, um, please smile on my desires. Forgive me.” Actually, she talks about herself in the third person. She says “smile on her desires/And take her into your arms.”

SCHILLINGER: There's a sense that the book in a way is an argument that she is a Magdalene, that she is someone whose sins might be forgiven.

OROPESA: But again, the oboe comes back and drags her back into the minor mode and she says, “oh, everything is over.”

PLOTKIN: And she circles around [Italian], and all of those “t’s” require a shortening of breath, it's as if she's gasping. And she finally at the very end says [Italian] running out of breath, [Italian] it's all over, with just a thread of a voice.

And that reaching up an octave is the last grasping for the glorious sound, the high soprano sound that represented her beautiful youthful days of just a few months before, but now it's almost extinguished. It's just a thin thread of voice. It's all she had. She's dying.

Reflections

SCHILLINGER: When she died at 23 of consumption there was a funeral for her, and many of her past lovers, noblemen, counts, attended, and they followed the hearst to Montmartre to the cemetery where she was buried. Initially she was buried in an ignominious section of the cemetery, but it was a grave that would have sort of expired after five years. And when the count who had actually married her learned of this, he arranged for her body to be moved into a permanent section of the cemetery, and that's where her grave is now. And people still leave white camellias all over the grave of Marie Duplessis at Montmartre.

TURTURRO: And I think that's really something beautiful, because you feel for her and you, you love her. And, uh, you kind of die with her, you know, uh, even though you haven't lived that life, and that's the whole idea of where music can take you and storytelling can take you.

SCHILLINGER: Seeing that her struggles weren't vain and that the aura of her personality is preserved by these words, by the music, is just tremendously powerful. And she could never have imagined that her legacy would be as great and as enduring as it has been. It turns out if you do tell a fallen woman's story as feelingly and as fully as Dumas did, and as Verdi transformed it, they don't really fall at all.

GIDDENS

Translator Liesl Schillinger, soprano Lisette Oropesa, writer Fred Plotkin, and actor and director John Turturro decoding “Addio del passato” from Verdi’s La Traviata. Lisette will be back to sing it for you after the break

MIDROLL

Violetta has sacrificed everything for love. Now, as she lays dying, she says farewell to her happy dreams and memories, and she asks for God’s forgiveness in “Addio del passato.” Now let’s listen to Lisette Oropesa break all of our hearts.

“Addio del passato”

Violetta Valéry and the real-life Marie Duplessis will live on forever in “Addio del passato” from Verdi’s La Traviata, especially in that incredible performance by Lisette Oropesa.

Next time, we’re off to Russia to meet one of the unluckiest politicians of all time... Boris Godunov.

Aria Code is a co-production of WQXR and The Metropolitan Opera. The show is produced and scored by Merrin Lazyan. Max Fine is our assistant producer, Helena de Groot is our editor, and Matt Abramovitz is our Executive Producer. Mixing and sound design by Matt Boynton and Ania Grzesik from Ultraviolet Audio, and original music by Hannis Brown. This project is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts. On the web at arts.gov.

We love reading your tweets and reviews of the show, and it’s a great way of spreading the word, so keep ‘em coming!

I’m Rhiannon Giddens. See you next time.

TURTURRO: All right. Ciao. Ciao. Ciao. Ciao. Bye.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.