Strauss's Elektra: Waltzing With a Vengeance

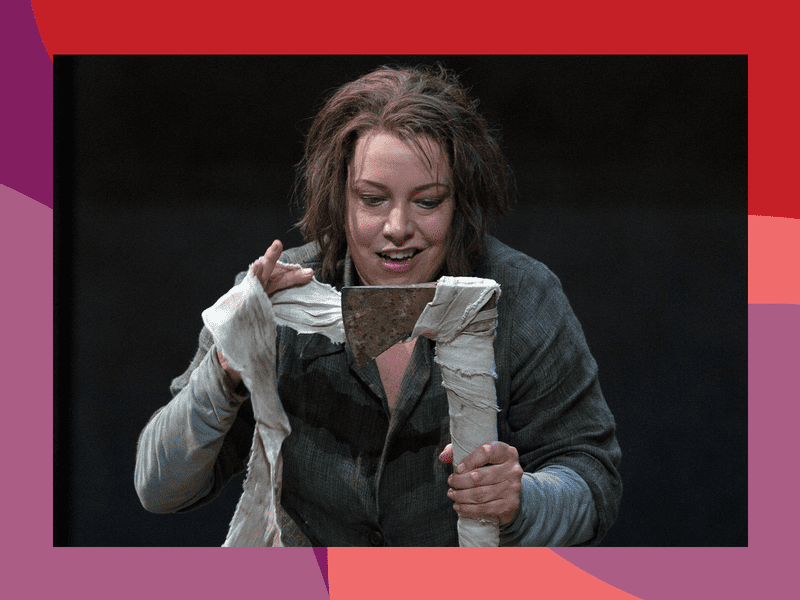

( Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera )

Aria Code S3 Ep 8

“Allein! Weh, ganz allein”

from Strauss’s Elektra

Just a heads up: This episode includes descriptions of childhood sexual assault, so if you want to skip this one, we totally understand.

BILLBOARD

Theme music

BERGER: We’re in the world of feelings here. There’s no true and false, and there’s no safe and unsafe. It’s all scary and murky and it’s an intense inward journey.

GIDDENS: From WQXR and the Metropolitan Opera, this is Aria Code. I'm Rhiannon Giddens.

STEMME: Your day will come. Everything will work for you so that you can have your revenge.

GIDDENS: Every episode, we dive deep into a single aria to see what’s below the surface. Today, it’s “Allein! Weh, ganz allein” from Elektra by Richard Strauss.

HOLTHOUSE: My happy place smelled of gunpowder and blood and felt like a pistol bucking in my hand as I pulled the trigger. I imagined it all.

GIDDENS INTRO

OK, I’m gonna say it: There’s no opera more terrifying than Elektra. It’s a violent revenge fantasy mashup of Greek myth and Freudian psychology. Basically a long primal scream accompanied by a huge orchestra.

The title character Elektra comes from the most seriously dysfunctional family in the grand tradition of dysfunctional families. Her father killed her sister. Her mother killed her father. And now, the only thing getting Elektra out of bed every morning is the drive to kill her mother.

So in the aria, “Allein! Weh, ganz allein,” you hear Elektra work herself up into a frenzy as she plans her revenge, and it’s gory and graphic as hell. Elektra finds herself alone, which is what the title means -- “allein.” She’s alone with her traumatic memories of her father’s murder; alone with her grief; and alone with her obsessive vision of dispatching her mother, slaughtering some horses and dogs for good measure, and then dancing herself silly all over their corpses while blood flows all around her. As one does.

But here’s the thing about Elektra: The most terrifying thing in the opera isn’t what happens between the characters onstage. It’s what happens in their minds -- and y’all, it’s dark in there. Real dark.

Luckily, three brave guests are going to light our way.

First, soprano Nina Stemme.

STEMME: When I first heard Elektra as an audience, I did not understand the music at all. And I was far from even dreaming that I once would sing this role. So my experience told me that I need to invest a lot of time and energy and my own soul in understanding this role.

Next, William Berger, an author, lecturer, and radio commentator.

BERGER: I took a friend to see Elektra, someone who’s not a typical opera goer. And he was a little put off by the character and her music, and he was saying to me, “Why is she screaming at me like that!”

And third, David Holthouse, a writer and documentary filmmaker from Alaska, who knows what it’s like to be consumed by the desire for revenge.

HOLTHOUSE: For three years in my early 30s, the desire for revenge was my constant companion. As long as I kept that fantasy burning, I could live.

And just a reminder, David's story includes descriptions of his experience with sexual assault. So this would be the right time to sign off if you'd prefer not to hear about that.

Okay, it’s time for “Allein! Weh, ganz allein” from Strauss’s Elektra.

DECODE

BERGER: Elektra is about psychological discoveries and they're not pretty.

The title character is named Elektra. She is the daughter of King Agamemnon, who led the Greek troops during the siege of Troy, and his wife queen Klytämnestra. When Troy fell, Agamemnon returned home and was murdered by Queen Klytämnestra and her lover, Aegisthis

STEMME: And Elektra’s love for her father is so great that she is totally obsessed by taking revenge on her mother.

HOLTHOUSE: When I was seven, I was obsessed with Star Wars. And I had a big crush on Princess Leia. I played baseball and I went fishing in the summer. My parents had just moved to Alaska, and so I was still finding my footing in a new place. When my parents moved, some close friends of theirs moved with them. My parents socialized with this other family frequently, and this other family had a teenage son. I really looked up to this guy. He was a star athlete. And I was an only child and I sorta regarded him as a big brother. And he treated me like a little brother up to the point that he raped me.

BERGER: When this drama begins, Elektra has been living in the courtyard of the palace with the dogs and the animals. She’s an outsider to the inner court of Queen Klytämnestra.

STEMME: I think this puts her in a terrible state of mind because she's excluded from society.

BERGER: Elektra is regarded as deranged and degenerate, “Okay, fine. Your father has been killed, but what are you going to do about it now? How are you going to have a life?” And Elektra is decrying what Klytämnestra has done not only that she's murdered Agamemnon, but she's murdered him twice by giving her body to such a lesser man as Aegisthis, that this is a way of really defiling Agamemnon's memory.

HOLTHOUSE: Our families often would get together for dinner, and, uh, one night, this teenage boy got me down to the basement and he had a collection of martial arts weapons -- samurai swords, nunchucks, ninja stars, that kind of thing. And he started sort of threatening me, throwing the ninja stars at my head so they'd stick in the corkboard on his wall next to my head and whirling the nunchucks in my face and looking back now, I see what he was doing was terrifying me into submission, which he did when he drew the samurai sword and put it at my throat.

I remember thinking that maybe, maybe this was still some kind of game and that I was going to be alright, but I wasn't alright. And it wasn't a game.

I can still remember my face being pressed against the black plastic, you know, of a 1970s waterbed mattress. And he put a pillow over my head so that my parents and his parents who were upstairs, I think playing board games, wouldn't be able to hear me screaming.

I just disassociated from my body. I think that my seven year old brain was like, “This is too terrifying and too painful. I can't handle this.”

And then when it was over, he gave me some tissues to dry my eyes and sat me down in front of an Atari and gave me some candy. And, uh, you know, told me that what just happened was a bad thing. And that if I ever told anybody, he would come to my house in the middle of the night and use that samurai sword on me and gut me like a salmon.

BERGER: One thing that Freud explained about trauma, is that you re-enact it throughout your life until you fix it, address it, or in most cases you don't, you just keep re-enacting it, that's part of what the Greek myths said happened cyclically from generation to generation, Freud said, yeah, they also happen cyclically within the individual over and over. Ad infinitum.

HOLTHOUSE: Well, the nightmares started almost immediately and the flashbacks, and so I just lived in sort of a constant state of fear and rage. I started drinking when I was seven, you know, I'd wake up in the middle of the night and, you know, hit my parents' liquor cabinet, because I felt like the messaging I was getting from adults was that the world is fundamentally a good and safe place. And I thought that either these people don't know about the monsters, which are all around us, or they know about the monsters and they're just not telling me. And uh, either way I felt abandoned by the world. And so I didn't tell anyone and not telling anyone was about as lonely as lonely can be.

Monologue - Beginning

STEMME: So at the beginning of the monologue, Elektra finds herself totally alone.

BERGER: There's no one else there on the stage. So she starts “Allein,” “I'm all alone.”

STEMME: And she tries to invoke the ghost of the father.

BERGER: She's talking to Agamemnon. Okay, he's not there and he's dead and that's the whole problem, but it's no less of a dialogue for that.

STEMME: When I sing about him, sort of almost shying back in his tomb, you can also hear the chromatic in her voice.

BERGER: That's when you use all of the notes that are really close together between one point and another, step by step.

STEMME: Which continues downwards by the orchestra. Also a chromatic movement, which says a lot about him going down in the tomb, but also chromatics, they have a very emotional, if not even erotical sense to them.

And you can hear how strong her love is for this person, Agamemnon, which is an extremely singable name. It's so beautiful. “Where are you? Why didn't you defend yourself?” she asks.

She just begs him to collect his forces and come up to her from his grave.

BERGER: I believe she does this all the time. Not only once a day, “It's 10 o'clock, time to sing ‘Allein! Ganz allein,’” but constantly.

STEMME: I think this is a recurring picture that is the murder of her father.

BERGER: She's living out this response to trauma.

HOLTHOUSE: I'd relive the rape in two ways. There would be nightmares where I’d wake up whimpering, grinding my teeth, and I would relive it when I was awake, and I would be triggered by certain sounds or places. In my teenage years, I just got a little better at sort of shunting them off the side, but they always stayed with me. It stays with me to this day and I'm 50 years old now, so yes, I've relived it a million times or more.

STEMME: Elektra says, “This is the time when you were slaughtered by your own wife and the one who actually slept with her in your bed.” Where she's talking about the murder, Strauss keeps repeating the same note several times. So it becomes like a ritual. And then she keeps going on how they hit him as he was taking a bath and how the blood runs all over the place. And that he comes back with a purple wreath where the blood is just, coming out from, from the open wound. It's really awful the text that Elektra has to sing, and I feel as an artist that I can't really portray it strongly enough. But luckily here we have the orchestra who gives all the colors to this text. So if one doesn't hear the text, you can listen to the orchestra, it's quite amazing what's going on there.

BERGER: We hear these famous dissonances and weird orchestrations of shrillness that are still remarkable today, even to our post rock-and-roll and airplane jets ears.

Her vocal line rises through the scale, climaxing on the words “bleeding wound.” The orchestra thunders out, and she exclaims, “Agamemnon!” It's like the musical equivalent of an adrenaline rush. It demands that you pay attention.

HOLTHOUSE: For me, the turning point came when I was 31, and I suddenly learned that the man who’d raped me when I was a little boy was living nearby, in the same metropolitan area. And the knowledge that I could run across him by chance in my daily life triggered what I now know was, you know, full-blown post-traumatic stress disorder. You know the feeling when you stumble and catch yourself and you get that little jolt of adrenaline? Imagine that feeling 24/7, imagine existing in a constant state of adrenaline rush. It's horrible. You can't sleep. You can't concentrate on anything. And for me, the antidote, at first, was fantasizing about wiping the threat off the face of the earth, the antidote was fantasizing about killing the man who'd raped me.

STEMME: This is a longer section now when she describes his eyes and his gaze and how he sort of commands her to take revenge. When I sing a piece like this, I have to be careful that I don't try to compete with the orchestra because in Elektra, Strauss uses one of the biggest orchestras ever in opera history, with over a hundred musicians, in order to give colors to the drama. And I have to really save my voice and make sure that it still carries above the orchestra. I heard about one rehearsal in Dresden and when he was still supervising the first production and he told the orchestra, “Play louder, I can still hear the soprano!” And that's what it feels like sometimes.

BERGER: This monologue shows you the range of human psychology. We're in the world of feelings here. There's no true and false and there's no safe and unsafe. It's all scary and murky and it’s an intense inward journey. It's not Agamemnon who's coming home, it's almost Elektra herself who's coming home on some level.

STEMME: I really love this moment when she becomes totally vulnerable and just a little girl, invoking her father, you can hear she sort of becomes the little daughter that sat on his lap and said, “Daddy, father, Agamemnon, I have to see you. Don't leave me alone today. Please come back just like you did yesterday, like a shadow in that little corner of the wall. Please show yourself to your child.” You can hear the most lyric part of this scene in the orchestra. It's so beautiful. But of course, that doesn't last for long.

This music gives Elektra hope and she is sort of talking to her father, and telling him that “Your day will come, everything will work for you so that you can have your revenge.” It's not only that she reassures him, above all she reassures herself that this will happen. This is the goal of her life.

HOLTHOUSE: As soon as I started fantasizing about killing him in the same granular graphic level of detail as I was reliving the rape itself, I started to feel better. I started to feel a lot better. I could sleep, I could eat, I could work. I could socialize. As long as I kept that fantasy burning, I could live.

BERGER: But that comfort, that comfort that we find in the melody, it's a delusion. “Go to your happy place,” my dentist is always saying when he needs me to relax my jaw, because it feels good in the moment, but it's absolutely delusional.

HOLTHOUSE: My happy place, you know, smelled of gunpowder and blood and felt like a pistol bucking in my hand as I pulled the trigger, and someone moaning in pain. I imagined it all, because it was a way of supplanting the reliving of the rape.

BERGER: And this is when she starts really graphically describing this day of fulfillment when the blood of a hundred throats will cover your grave. First of all, she's going to drain the blood of Klytämnestra and then there will be the animal sacrifices just to emphasize the royal status of the dead Agamemnon.

STEMME: Because this is after all built on the Greek legend. So there has to be a sacrifice, not only humans, but also the horses or the dogs

BERGER: Which is like, “No, what don't do that.” But this was science of their time, “I need to put their blood on this grave or the problem continues.”

HOLTHOUSE: Envisioning exactly how I was going to kill him, it had a very calming effect on me. And that worked for about four to six months, and then the fantasy wasn't enough and the nightmares and the flashbacks and the constant adrenaline rush came back. And so I had to effectively increase the dose of the antidote, from fantasizing about killing him to actually plotting to do it. I would stake out his house, just trying to figure out what his daily life was like, learning his routines, and probing for vulnerabilities. And after another four to six months, that wasn't enough, and I had to jack up the dosage again to actually taking very concrete steps to kill him. So I went to Phoenix, Arizona and bought a gun, a Beretta 9-millimeter with a couple of homemade silencers. And then I took the gun to a kind of street gang gunsmith who altered the barrel to try and throw off any sort of ballistics testing. It's basically like adding a bunch of extra lines to a fingerprint, to make it untraceable.

BERGER: What's remarkable about this aria is not either the dissonance or the lyrical moments, but the wide space between them. How lyrical the lyrical moments are with that post-romantic orchestra sawing away in the violins and violas, it's so beautiful. And then on the other hand, we have like brass and even some instruments used as percussion kind of rattling our nerves. Here's Strauss saying, “I know both ends of the spectrum and I'm perfectly capable of bringing them alive.”

She's talking about a swelling torrent of blood flowing from the throats of her sacrificial victims. And at this point, the orchestra actually swells and ebbs like a bloody river.

STEMME: It is a real current in all instruments, and then also the life just crushes down and you can hear that actually her voice crushes down over an octave. So the current, it sort of ends in a catastrophe.

HOLTHOUSE: A few weeks before I was gonna kill him, my parents called me, out of the blue, and my mom did most of the talking and then she said that she'd found a childhood diary of mine when they were cleaning out my room. And in that diary, which I'd kept when I was 10 and 11 years old, between writing about my grandfather dying and about hitting a game-winning double in little league, there was an entry about how I understood that what had happened to me, was called rape. And so my parents wanted to know if what I'd written was true. And I'm sure that as soon as I hesitated that part of them died because they knew in that moment that it was true, and I knew in that moment that they knew. So this carefully cultivated plan had to be abandoned because what I'd always thought was shielding me from suspicion was the fact that the rape was a terrible secret. You know, I had no desire to go out in a blaze of glory or spend the rest of my life in prison. So I had to find something else to try and medicate, to treat myself because immediately the nightmare started to come back. And what I found was writing about it. So that's what I decided to do. I decided to confront the rapist and I decided to write about all of it, which was another form of vengeance. Like if I couldn't kill him, I could at least destroy his reputation. And I could at least make everyone around him aware of what he was.

STEMME: When everything is brought to an end, Elektra will dance on his grave to show what a huge king he was. How worthy he was of this revenge.

BERGER: She talks about dance and she's going to dance around your grave with the steam of blood hanging over the palace. She’ll lift her knees high as she dances over the corpses. And this is of course Vienna in the first decade of the 20th century and dance is a waltz. But it's not a waltz as we should expect, “Oh wasn't that beautiful at the ball we went to last night?” It's much weirder, but not totally unrelated from the idea of a happy memory of dancing a waltz.

HOLTHOUSE: Looking back on the time when I was plotting this murder. I lived behind this dance club called The Church and every weekend, I'd go out on a dance floor that was full of people, a lot of them were drinking, a lot of them were high on cocaine. And I was high on plotting to kill this guy. And I would just dance to this really dark banging techno music. And I would just lose myself in it. And when I was closing my eyes and dancing to the music, what I was picturing was the bullets hitting his body and the feeling of the gun in my hand. And, the relief of that and the joy of it, and the exaltation, I'm sure to anybody looking at that dance floor, they're just like, “Man, look at that guy, like rocking out, like, what is he on?” And what I was on was the unadulterated pleasure of envisioning vengeance.

STEMME: I think I really make use of the big dancelike rhythms here to work myself up to a long and high top C. But I can't do it too much when I'm on stage, because then I won't have the breath to keep the long sustained notes. She has to turn her psyche inwards out to sort of purify. It's like a cathartic moment.

Reflections

STEMME: At the end of this opera, I feel totally emptied, and I know that I always try to look perfectly normal afterwards, which is a bit strange. I've seen pictures of myself coming out from Elektra performances. And I can realize that I'm not quite myself, no, because what I've been going through emotionally and vocally, there's just nothing like it.

BERGER: Every great opera is a journey of one sort or another, but this one Elektra feels to me urgent. It's not pretty, it's something I have to do for some sense of wholeness.

HOLTHOUSE: I really believe that child molestation is a form of murder in that whoever that child was going to otherwise be is dead. I mean, the natural process of being innocent as a child and sort of gradually having your innocence stripped away by life until you can see the world with adult eyes, that process is terminated and you are slammed into seeing the world with jaded eyes at a very early age. And so, in a sense, your childhood is murdered. You know, it's just, it's over.

And I did feel a tremendous sense of satisfaction knowing that I'd done him a great deal of harm and to possibly make him think twice before he victimized any other child. I fulfilled my promise to avenge the little boy that I once was and, uh, the person that he could have become had he not been raped when he was seven.

GIDDENS

Writer and documentary filmmaker David Holthouse, soprano Nina Stemme, and author and commentator William Berger...

...decoding “Allein! Weh, ganz allein” from Elektra by Richard Strauss. Nina will be back to sing it for you after the break.

MIDROLL

Elektra’s father has been murdered, and now all she can think about is revenge. In “Allein! Weh, ganz allein,” she moves from agony to ecstasy as she imagines the gruesome murder of her mother. Here’s Nina Stemme on stage at the Metropolitan Opera.

“Allein! Weh, ganz allein”

Part primal scream and part Viennese waltz: “Allein! Weh, ganz allein” from Elektra by Richard Strauss, sung here by Nina Stemme.

Next time, we’ll take a step back from the abyss with a high-flying aria from The Tales of Hoffmann.

Aria Code is a co-production of WQXR and The Metropolitan Opera. The show is produced and scored by Merrin Lazyan. Max Fine is our assistant producer, Helena de Groot is our editor, and Matt Abramovitz is our Executive Producer. Mixing and sound design by Matt Boynton and Ania Grzesik from Ultraviolet Audio, and original music by Hannis Brown.

I’m Rhiannon Giddens. See you next time!

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.