Puccini's Turandot: Bewitched, Bothered, And Beheaded

William Berger: What is this woman in white that we're waiting for? Is she purity and virginity or is she death?

Rhiannon Giddens: From WQXR and the Metropolitan Opera, this is Aria Code. I'm Rhiannon Giddens.

Anna Chlumsky: You end up being the center of a solar system, and everything's spinning around you somehow, and it is thrilling. It is terrifying. It is exhilarating.

Rhiannon Giddens: Every episode unwraps a single aria so you can see what's inside. Today it's “In Questa Reggia,” which means in this palace from Puccini's Turandot.

Anna Chlumsky: Then when she gets to sing, it's not, "Look at how nice I sing," it's, "Here's why I sing."

Rhiannon Giddens: Now, this season on Aria Code, we've been focused on the many forms of desire, how it shows up in our own lives and how the best moments in opera express those feelings. This episode is the upside-down of all that. It's about suppressing desire, cutting yourself off from your own feelings and the rest of the world. Sometimes it's for good, healthy, and self-protective reasons. Let's talk about Turandot, Giacomo Puccini's final opera. Turandot is known as the Ice Princess.

She's sworn off all intimacy and love forever and she's not just playing hard to get, she's legitimately very hard to get. She presents suitors with three riddles and if they don't solve them all correctly, she puts their heads on spikes and adds them to her growing collection. It's like The Bachelorette, but a little bit bloodier. In walks the tenor, Prince Calaf with his father Timur, and the slave girl Liu in toe. Now, this dude obviously likes a challenge because he's undeterred by the prospect of the whole heads-on-spikes thing.

Heads on spikes, just reiterating that. He's got swagger and he wants to win the princess, so he's up for the riddles. Now, it seems simple enough, but Turandot's entrance aria, In Questa Reggia shows us the story is deeper than it appears. In the aria, Turandot explains to Prince Calaf why she rejects love. It turns out her ancestress, Princess Lou-Ling was defeated, raped, and killed in this palace, “In Questa Reggia.” Turandot wants to avoid her fate and avenge it. If you scratch just below the icy surface, this princess's story is about pain and trauma that's passed down through generations.

Turandot has walled herself off. She will not be defeated by any man, and she will not be defeated by love or so she thinks. Well, three great guests are here to decode this battle of the sexes. First, Soprano Christine Goerke, who sings the role of Turandot at the Met. Her very first performance as the Ice Princess brought a few challenges even beyond the epic singing.

Christine Goerke: I was pregnant with my second child.

Rhiannon Giddens: That would make it hard to believe that she's sworn off all men.

Christine Goerke: We had some fancy footwork to do and by fancy footwork, I mean I moved sideways [laughs] in the costume, it worked.

Rhiannon Giddens: Next, William Berger, author, lecturer, and Met Opera media commentator. He wrote the book, Puccini Without Excuses.

William Berger: I'm a big fan of Puccini and of all opera because I'm a fan of people telling me intense stories. Lately, mostly I get those intense stories through heavy metal, but I enjoy them wherever I can find them.

Rhiannon Giddens: Anna Chlumsky, an actor and opera nerd.

Anna Chlumsky: That's exactly what I am.

Rhiannon Giddens: She's probably best known for playing political staffer Amy Bruckheimer on the HBO series Veep and she's currently leading the cast of Inventing Anna, an upcoming drama series from Netflix. She got bit by the opera bug while starring in the comedy, Living on Love with co-star Renee Fleming.

Anna Chlumsky: Then I just became actually obsessed. The music gets into parts of us that we can't even define. It can tell so much more story and connect so much more deeply than if we were just using spoken text. I love spoken text because that's my job, [laughs] but it's undefinable what music can do.

Rhiannon Giddens: All right, here we go, right through the palace gates. “In Questa Reggia” from Puccini's Turandot.

[music]

William Berger: Turandot was Puccini's final opera. In fact, he died before he was able to finish it. He had writer's block for a couple of years before his final illness. He had worked himself into a corner deciding to create the ultimate drama of the tension between male and female. The music for Turandot was not only some of the best music Puccini had ever written but in many ways, new directions that he was discovering in himself as a composer at this late stage of his life.

Anna Chlumsky: This is set in a fantastical China imagined by an Italian composer, loving the music that he heard on a music box from afar.

William Berger: We have one tune, “The Jasmine Flower,” which is an actual authentic Chinese melody, and he orchestrates it in an Italian way so that it's neither Chinese nor European. It's something neither and both.

Anna Chlumsky: My husband is Chinese American. My in-laws are from China. My daughters are Chinese American. This opera itself is a culturally appropriated concept. That's what we would call it today and I often joke that I'm an actor, so I'm an appropriator for a living. I'm not playing myself; I'm playing somebody else. There are definitely ways in which you can interpret a culture that is not your own with extreme ignorance. If we get it wrong, then we need to learn from that, but I don't see that in this opera. My family doesn't.

[music]

William Berger: We have a really unusual situation in Turandot. Puccini has been teasing us throughout the whole night. He's named the opera after her, and we haven't heard a peep out of her.

Anna Chlumsky: The whole first act and first scene of the second act are other people talking about this woman. It's their interpretations of her.

[music]

William Berger: The score says that her palace rises in the background as if from the mists, and then she makes a hand gesture literally and off with his head to a prince who has failed the tests. Then she subsides again into the darkness.

Anna Chlumsky: She is put up there on display, something untouchable, something to react to or against, but she is voiceless. She is an object.

[music]

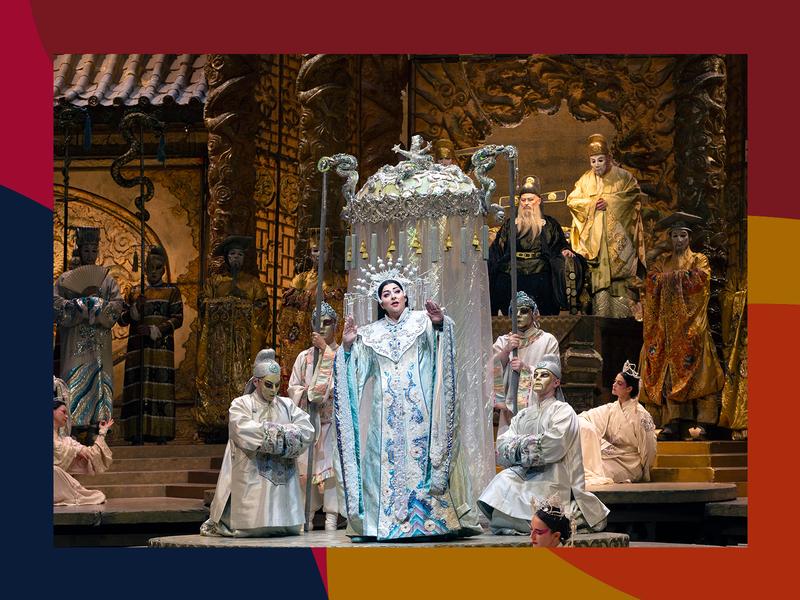

Christine Goerke: We see her coming into the beginning of “In Questa Reggia” with usually great pomp and circumstance. It is wildly intense because once you step foot into the story, you have got to immediately come up to the level that the first half of the opera has brought you to. You end up being the center of a solar system and everything spinning around you somehow and it's thrilling, it is terrifying, it is exhilarating.

[music]

People are really anxious to see, "Right, okay, well, what is she going to be like? What is she going to say?"

William Berger: "What is this woman in white that we're waiting for? Is she purity and virginity and all the promise held in that, or is she death?"

Christine Goerke: Turandot is if you go with the usual interpretation, an icy bitch, but she has good reason. She has taken upon herself the persona of her ancestor, Princess Lou-Ling and this beautiful, graceful, sweet, wise woman had to consistently fight off domination from foreign princes and things did not end very well for her. Turandot has an innate fear and anger towards men.

To protect herself, she has come up with three riddles and the only way that a prince can have her, can have the kingdom, is if he answers all three of these questions correctly.

William Berger: She's not on stage very long, but when she is on the stage for however many minutes it is, you'd have to ask the soprano. She would know.

Christine Goerke: 22-23 minutes total.

William Berger: Every one of those moments has to be extraordinary.

Anna Chlumsky: Then when she gets to sing it's not, “look at how nice I sing,” it's “here's why I sing.” Choosing to take the time and so much orchestral energy and vocal energy to let her tell her story and earn her actions. That is a very modern concept.

Christine Goerke: You are walking out into a situation where you have 6,000 colleagues on stage and the entire orchestra has been wailing and it's been amazing, and everybody has been singing, and all of a sudden, the only thing that you get is this tiny D major chord. You have to start singing.

[music]

It's not high, it's not low, but you have to be so assured in that moment because if you are not, you are setting the tone for the entire aria. It's actually quite scary to make that first entrance. Once that's over, I can breathe a time of relief for about two minutes.

William Berger: This aria begins telling us the story of something that happened thousands of years ago, and this is already thousands of years ago so we're in the way back machine. She's telling us a story.

Christine Goerke: Once upon a time. Many years ago, her beautiful and serene ancestor, Princess Lou-Ling was a wonderful ruler and peaceful and joyful.

Anna Chlumsky: She obviously identifies with this historical figure, my ancestors, la mia avo.

Christine Goerke: There was a time when the kingdom not only was dominated and conquered, but she was attacked and raped and killed.

Anna Chlumsky: She's violated.

William Berger: In this very palace, In Questa Reggia.

Christine Goerke: Where her young voice was stifled.

William Berger: Wouldn't it as coincidence had it, the King of the Tatars? Calaf is the Prince of the Tatars. Though this was thousands of years ago, the soul of her ancestors is reborn in her and she will have revenge for what happened to her.

Christine Goerke: No man will ever have me. No man will ever do that to us again.

Anna Chlumsky: I get to sing. My voice gets to be heard because her voice was stifled.

William Berger: Part of what Turandot channels from her ancestors, the Princess Lou-Ling, along with the beauty and all the tenderness are the fear and the hurt that come along with her violations centuries ago. This becomes part of Turandot's, I wouldn't say anger, just her righteous indignation. It morphs into a more aggressive personality trait.

Christine Goerke: We all put on that mask of strength when we need to. That's what she does. I feel like she's almost numb at this point. She's had to do the same thing over and over and over again. It's difficult for her I believe. There is something different about this guy. She's attracted to him. She's never been attracted to anyone before. She hated all of these other people, but she had some desire for him. That's terrifying. Who knows if that's what happened with her ancestor? Who knows if that was the mistake she made?

[music]

At the beginning, she says "E quel grido traverso stirpe e stirpe."

[music]

Qui nell’anima mia si rifugiò.

This is talking about the cry that passed down through all the generations and took refuge in my soul.

William Berger: Then when she talks about her connection to her ancestors who is reborn in her, you'll hear the whole atmosphere changed. The music becomes a little bit more lush.

Christine Goerke: Talking about Principessa Lou-Ling, it's really a warm part of the voice. To me, it feels very familial. From this section from Pure nel tempo, it's talking about this uprising and the kingdom being conquered. The vocal line does begin to rise up and up and up and up. It's almost as if you were having a conversation and you're telling a story about something that really upsets you and you get to a point and then you remember that you're not supposed to be getting upset about it.

Then when she comes back [laughs] down, she is starting to talk about her ancestor again. She says, "My beautiful ancestor was dragged off, was killed by a man like you".

William Berger: She points to Calaf, "very like you Prince of the Tatars. I'm going to get you and all of you men for this."

Christine Goerke: Doesn't matter any man you are that guy. Every guy who shows up. You are that guy. Then there's a lot of dotted rhythms and if you think of dotted rhythms, it's a bit almost like marching, unwavering military. It's almost like an angry heartbeat for her, and it happens over and over again throughout this aria. It dawns on her, "This is going to happen to me. I'm going to be raped and I'm going to be killed. That's what happens when men show up and they conquer this land." It's been taught to her. It is ingrained in her, and she's terrified from this trauma from generations past.

Anna Chlumsky: It's like intense. It is violent. It feels the way this story feels. It's the stifling of that voice from ages ago.

[music]

William Berger: What Turandot is saying about here is the trauma that doesn't go away over time. The fact that there are thousands of years and that the players are still exactly the same. Here are the Tatars with their flags unfurled, coming after her in this very palace shows us that time doesn't heal all wounds. There are some that are played out and recreated with every generation.

[music]

There's research that tells us this is what actually happens to people. That trauma is passed down over generations, lots of generations. It's called Historical trauma or intergenerational trauma. This can show up for descendants of people who've gone through slavery, war, genocide, extreme or systemic poverty. There are different theories about how it's passed on, maybe through survivor's parenting techniques. Maybe it's transmitted during pregnancy. Maybe the survivor's environment actually affects the way that the genes are expressed.

It's crazy but it exists. Turandot is telling us something very real here. She's telling us that some conflict lasts forever. Sometimes when people say you should look for closure, or people should just get over it, or that happened a long time ago, we're saying that that's not good enough. Puccini had a way of showing us that same truth.

[music]

Christine Goerke: The princes arrived, and they came from everywhere. All they bring is death and screaming and anger and sadness, and they've killed the purity of not only the ancestor but of the kingdom. From there, the voice starts to go up and you have nothing but catch breath. It'll be going, going, going, going, you have to quickly catch a breath and continue. You desperately have to stay connected to music. You desperately have to stay connected to the text. If you get upset about something, you start to feel it in your throat and you get really upset.

That is absolutely what you cannot do while singing this. Our job is to get right up to that line of emotion and then take one hair of a step back. It's like walking a tightrope here, a really loud, amazing tightrope. [laughs] Then Puccini drops the orchestra out and leaves you on this obscene high B thanks for nothing. On the e quel grido scream. It is powerful and violent. Two seconds later, he has this gorgeous, lush legato phrase in the middle of the voice, which is beautiful.

[music]

That's so amazing because it shows that there are so many different facets of this woman of her psyche of her personality of her voice.

[music]

Anna Chlumsky: She's saying, no man will ever possess me. To me, that shows her fears of men, and the fear of violence, and the fear of losing herself. She thinks she's got it figured out. I'm going to make sure it never happens to me by just killing them all. She has committed herself to this life of isolation, blood, and destruction.

William Berger: It shows us how a person goes from hurt and abused to becoming the one who hurts and the abuser. She becomes this oppressor, a mass murderer just trying to balance out the karma of the pain that happened centuries ago.

Christine Goerke: Yet she's still a human being, and she still does have a heart. It's really vulnerability. It's difficult to make the character of Turandot very multi-dimensional. We are definitely given a strong view of her from the minute she walks in the door. It's my favorite thing to do to find characters like this and to try and get the audience on my side somehow. To see why a character behaves the way that they do. Does it make you fall for them? Does it make you feel like they are right? Not necessarily.

Even if I have a couple of people walk out of the theater saying, "That wasn't the right choice necessarily," but I understand why she's the way she is. That's my job.

[music]

William Berger: Then she turns to the straniero, to the stranger, the foreigner, Calaf and says, "Oh, don't tempt fortune, because the riddles are three and death is one."

Anna Chlumsky: I got some riddles, but we got an answer. The answer is death. Everybody just go home we're done.

William Berger: He dares to correct her. He mansplains it to her and he says no, the riddles are three and life is one.

Anna Chlumsky: He is spreading that message that death breeds death breeds death. How about we choose something else? How about there's a new thing we can do? Let's choose life.

William Berger: The climax is both of them hitting the high C and seeing who lasts longer. You'll hear that face-off as they contend at the end of this aria. This is not a man and a woman in a life-and-death struggle. This is all the negative and positive energy that has ever existed in the universe funneled through a man and a woman in contention. This is matter and antimatter.

[music]

Christine Goerke: Immediately after “In Questa Reggia” since the prince is determined to go on with the trials, she wanders herself right to a good place to sing, and immediately says to him, "All right, stranger, listen up. Here are the riddles and she asks him the three riddles."

[music]

By the time he answers the third one, it's fraught with tension. I think that this is the first person who's ever made it to the third riddle. At this point, I feel like she doesn't know whether to wish that he doesn't get the answer or wish that he does.

[music]

He wants her to be in love with him, and she's terrified at the prospect of that. He sees how scared she is and says, "Okay, I answered your riddles, but I will give you till morning. If you find out my name, I will die. I will die for you; you will be free." That's pretty gigantic.

[music]

Anna Chlumsky: He is making himself vulnerable and he's proving to her that he is actually not out to get her. That makes her drop her guard and finally accept that maybe there's hope. Maybe not all humans are out to hurt, kill, maim, rape other humans. Maybe there's a such thing as love. Maybe there's no such thing as growth. That's where the hope comes in.

[music]

Christine Goerke: They end up together. She finally gives up this suit that she wears and allows herself to possibly have happiness, even though it's terrifying to her. That's something that she's never done. She has been strong many times in the past but the most terrifying move in our lives, I think, is often the strongest one that we can make.

[music]

William Berger: This idea that Puccini never finished this opera, I think tells us a lot. Not that it's a failure on Puccini's part, I think it tells us about the story being told, there can be no resolution to this. This is a continuing story. It is a form of endless melody because it's a form of endless drama and conflict. It's beautiful on the surface, but it's also very disturbing. It's the story of love itself. It has beautiful aspects and has violent aspects, and it has unresolvable aspects. Maybe instead of thinking of this opera as an unfinished masterpiece, we should think of it as an endlessly evolving one.

[music]

Rhiannon Giddens: That was Soprano Christine Goerke, actress Anna Chlumsky and author William Berger talking about In Questa Reggia from Puccini's Turandot. Christine will be back to sing it for you after the break. Here's Christine Goerke singing In Questa Reggia onstage at the Metropolitan Opera.

In questa Reggia, or son mill'anni e mille

Un grido disperato risonò E quel grido, traverso stirpe e stirpe

Qui nell'anima mia si rifugiò!

Principessa Lo-u-Ling

Ava dolce e serena che regnavi

Nel tuo cupo silenzio in gioia pura

E sfidasti inflessibile e sicura

L'aspro dominio, oggi rivivi in me!

Pure nel tempo che ciascun ricorda

Fu sgomento e terrore e rombo d'armi!

Il regno vinto! Il regno vinto

E Lo-u-Ling, la mia ava, trascinata

Da un uomo come te, come te, straniero

Là nella notte atroce

Dove si spense la sua fresca voce!

O Prìncipi, che a lunghe carovane

D'ogni parte del mondo

Qui venite a gettar la vostra sorte

Io vendico su voi, su voi quella purezza

Quel grido e quella morte!

Quel grido e quella more!

Mai nessun m'avrà!

Mai nessun, nessun m'avrà!

L'orror di chi l'uccise

Vivo nel cuor mi sta!

No, no! Mai nessun m'avrà!

Ah, rinasce in me l'orgoglio

Di tanta purità!

Straniero! Non tentar la fortuna!

Gli enigmi sono tre, la morte è una!

No, no!

Gli enigmi sono tre, la morte è una!

Rhiannon Giddens: A battle of the sexes never sounded so good. That was Christine Goerke laying down the law in the aria “In Questa Reggia” from Puccini's Turandot. Okay, the palace gates are closing, but before I go, here's a riddle for you. Ready? Here it goes. It showers joy upon the aria kingdom. It shines like a beacon drawing in new listeners. It shimmers like a star, or preferably five. Well, that's right. It's a rating or review in Apple Podcasts. Submit one and you can keep your head. Thanks to everyone who's recommended the show to someone.

You're all princes and princesses, in my eyes. Aria Code is a co-production of WQXR in the Metropolitan Opera. The show is produced and scored by the one and only Merrin Lazyan. Emily Lang is our associate producer, Brendan Francis Newnam and Helena de Groot of Public Address Media, our editors. Matt Abramovitz is our executive producer. Sound design and mixing by Matt Boynton and Ania Grzesik. Original music by Hannis Brown. I'm Rhiannon Giddens. See you next time.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.