Crisis in the Kremlin: Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov

Aria Code S3 Ep 11

“Dostig ja vïsshei vlasti”

from Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov

BILLBOARD

Theme music

KELLER: For someone who has all the power, he simultaneously has almost no power. He seems rather powerless.

GIDDENS: From WQXR and the Metropolitan Opera, this is Aria Code. I'm Rhiannon Giddens.

MORRISON: And power at the top comes and goes. These rulers of Russia can grab it in different ways and use it for tremendous violence on the poor people at the bottom.

GIDDENS: Every episode, we put an aria under the microscope so we can get a closer look. Today, we’ll focus on “Dostig ja vïsshei vlasti” from Boris Godunov by Modest Mussorgsky.

PAPE: All these leaders, all these big names in the history, they had everything they could have but inside theirselves [sic], their souls, their hearts, they are not happy.

GIDDENS INTRO

One of the greatest things about opera is how we get to experience different languages and cultures through the stories we see on stage. And I’m really excited today because this is the first episode featuring a Russian aria. Russia joined the opera party a little later than places like Italy and France, but they've given us some amazing pieces. One of the very best is Boris Godunov, which many people consider the greatest Russian opera ever written. And it’s a real source of national pride.

This was the only opera that the composer Modest Mussorgsky completed in his lifetime. He died pretty young, but he had a gift for painting a picture with music and he captured something essential about Russia and its people.

The opera is about a tsar who ruled in the late 1500s. Tsars were usually born to the throne, but Boris Godunov was elected after a succession crisis and his legitimacy was basically called into question during his entire reign. So it’s not going to go well for him in the opera. There’s a series of natural disasters, an accusation that he killed a child to take the throne, and then the Russian people themselves turned against him.

And what really makes this opera shine is that while it’s about this real-life tsar and his very real-life unraveling, it goes way beyond one man. The libretto, which was based on the work of the great Russian writer Alexander Pushkin, gives you this look at the challenges the Russian people faced at that time: floods, famines, threat of invasion, entire cities being wiped off the map and rebuilt.

Not a great time to be a sorta legitimate ruler. Boris Godunov’s monologue, “Dostig ja vïsshei vlasti,” is about holding power but feeling powerless at the same time.

Now look, I’m not exactly an expert on 16th-century Russian history, so let’s bring in the big guns!

First, bass René Pape.

René started singing the role of Boris Godunov more than a decade ago.

PAPE: There is everything in it, in this music. There’s the Russian soul, you know, the suffering, there’s a little bit of luck in it, a little bit of joy. The whole spectrum of transformation he has to go through.

Next, Simon Morrison, a professor of Music History at Princeton University. A lot of his work focuses on Russian opera, and he’s currently writing a book about Moscow.

MORRISON: Little did I know it’s going to take me 15 years, but… it’s about the history of the city from soup to nuts… or, you know, birch bark to present-day digital files and, uh, trolling.

And finally, Shoshana Keller, a professor of Russian and Eurasian history at Hamilton College.

KELLER: Sometimes I wonder, where did all this come from? I remember in social studies classes being fascinated by pictures of Russian onion domes. And I was not the world’s best language student but I was good at history. So I started to study that part of it.

All aboard the time-travelling Sputnik! We’re blasting off to Russia in the 1500s to meet Boris Godunov.

DECODE

The Historical Boris Godunov

KELLER: Boris Godunov as a historical figure, grew up in the center of the court of Ivan The Terrible, someone whose power is so awesome that you tremble.

He engaged in some absolutely horrific public massacres and we can credit him with being perhaps the first ruler in Russia to consciously use terror as a political tool.

So Boris Godunov became personally close to Ivan, close enough that he married the daughter of one of Ivan's most notorious henchmen. The Godunovs are now an intimate part of Ivan's family.

And then in 1581, the only healthy son of Ivan The Terrible died. It's a disaster, partly because it left Ivan with only one remaining legitimate son, Fyodor. Who's always described in the sources as feeble-minded.

So Ivan the Terrible then died of natural causes in 1584. And this now leaves Fyodor, this feeble-minded fellow as the tsar. He can't rule on his own. So what do they do?

MORRISON: Boris Godunov, the brother-in-law of Ivan the Terrible was elected czar although he was not part of the bloodline and everybody knew that and so immediately there was a sense of suspicion about him, you know, whether or not he deserved to be there.

PAPE: It’s about power, it’s about money, it’s about from what family you’re coming from.

MORRISON: He ruled pretty wisely for a few years. But then his luck turns, owing to the fact that there is a famine in the land, and, you know, deprivations as a result of that.

KELLER: This is the beginning of the Time of Troubles, Smutnoe vremya, in Russian. The years from about 1601 to 1604 in particular, were years of terrible famine in Muscovy. This growing kingdom that Moscow is the center of, but it’s not yet grown very big. Muscovy’s always prone to famine, but this one was unusually severe. It was cold, it was wet. Nobody could get crops to grow. And we think that maybe one third of the population died.

MORRISON: I mean, the ultimate power in the history of Russia is Mother Nature, and Mother Nature gives you fires and floods and famines.

So various rumors start that suggest that this famine is a kind of a curse caused by the supernatural, or is nature's revenge based on this demonic presence in the Kremlin. And it has to do with the fact that perhaps Boris Godunov was illegitimately on the throne.

KELLER: This was not in fact, the God-chosen tsar and God was therefore punishing Russia, for having this illegitimate tsar.

MORRISON: And that, he perhaps had an earlier son of Ivan the Terrible killed.

KELLER: And that is this boy Dmitri Ivanovich who was born to Ivan's sixth wife.

PAPE: The Tsar Boris is accused to have murdered this young boy which is not really proved in the real history.

KELLER: Most modern historians, in fact, do not think that Boris Godunov had anything to do with the death.

MORRISON: What really happened, whether or not Boris Godunov got to the power through illegitimate means, I mean, the Chronicles are silent

PAPE: I rather think he didn't do it. So it's better for my soul. I always feel innocent.

KELLER: But Boris had real enemies in the court. So he really beefed up his secret police and spy service in addition to Godunov’s confirmed habit of making his enemies disappear when he needs to. So his popular reputation absolutely collapsed.

And I don't think any ruler could have done well out of this period, but Godunov did tend to compound disasters that were not of his own making with behavior that just made it all worse.

PAPE: The character of Boris is really difficult. He has no joy. And he has all these, these enemies surround him, the population is not, not really with him, in these days it’s almost not understandable what was happening 400 years ago.

Pushkin and Mussorgsky in the 1860s

KELLER: Boris Godunov took on a new importance in the Russian imagination in the late 18th and early 19th century, when Russia really was positioning itself as one of the major European powers equal ideally to Great Britain or to France.

But how do you know you're a great nation? You need to have a great national story, you need to have written your history about why you are now one of the truly great powers.

So Alexander Pushkin, who was Russia's greatest poet, wrote this play in 1824.

MORRISON: Called Boris Godunov, which is quite Shakespearean in the sense that it has to do with the psychology of the ruler and rumor and slander and intrigue at the court, these very Shakespearian themes.

KELLER: Pushkin was very interested in trying to tease out what it is that makes us genuinely Russian. And some of it involved this question of the struggle to create a legitimate government and legitimacy is one of the issues at the heart of this whole story.

MORRISON: When you think about the history of Russia it's born out of trauma or as a, I think another historian put it you know, part of Russia's problem is that it came into existence as a kind of abused child. You have this kind of ritual, brutalization and hazing and occupation in which it was wiped off the map more than once. This idea of threats of invasion from outside, is baked in. So I think that that's in the backdrop of the work.

KELLER: There was now a parallel movement developing among composers, to create a distinctively Russian national classical music. Partly by picking up Russian folk melodies and incorporating distinctively Russian stories into our operas.

We jump ahead a couple of decades to the 1850s, 1860s, and Modest Mussorgsky and his little circle take these ideas much further, anchoring it in their version of the Russian national story.

MORRISON: He wrote this opera twice, for logistical reasons and for political reasons. The revised version was completed in 1872. It was a more liberal period in which you could actually put on stage works that had earlier been censured. And this was a period in the 19th century in which you had these rumors about people potentially assassinating the emperor.

And, this is a subject that actually deeply informs Boris Godunov.

PAPE: When you sing a role for the first time, you'll read a lot of literature about this time, about this specific person, you make a lot of research. And when you play, like we did it in New York, in this kind of historic costumes, it gives you of course another feeling. You don't know how people lived in that time. You have no idea, but you can just imagine.

MORRISON: Boris has three huge and great monologues within the opera. The first of them takes place after the coronation. The coronation scene is one of the great moments in this great opera because of the magnificent use of harmonized bell sounds. Russian bells don't actually play harmonies or melodies, they play discordant sounds that are magical and have the power to cleanse so that inanimate things are given spiritual powers and bells are one of those things. And these bells chime and, um, mark, his coronation and, um, there's already a sense of doom built into it because one of the things that Mussorgsky very cleverly does is he takes the orchestra and he has these chords that are introduced beneath the bell, chiming sound. And these chords are very dissonant. He's basically underscoring the idea that there's something wrong here.

KELLER: And in the coronation scene, you've got all the glory and the crowds, and the first thing he sings is how much his soul is troubling him. So for someone who has all the power, he simultaneously has almost no power he seems rather powerless.

PAPE: It seems to me that he is not happy to be the tsar, so that means he actually doesn't want to have the crown. But he's forced into that part. And so if you are forced to do something and you have no choice, you just do it.

Before the Aria - Nursery Scene

KELLER: This aria, this monologue of Boris’s takes place in the nursery of the Kremlin. The scene opens with Boris’s two children and the nursemaid playing games. Boris comes in and we get a very tender scene where expresses his love for both children in very individual ways, you know, he pats his son on the head. He expresses his great love for his daughter, who has been recently widowed. And it gives us someone who has real emotional depth. He's not just a flat villain. Here's someone who loves his family.

PAPE: He's a really human character. He's a kind father, a friendly father, even to the nurse he's nice.

MORRISON: The only joy in his life is his family. And right at the end of that section, he actually talks about the storm coming. And it's in his soul.

PAPE: As other kings I have played before he was full of problems.

MORRISON: He goes from A-Flat to sort of C-Flat, uh, all flats here. So we're heading sort of in real downturn in terms of the musical language, to the flat side and maximum flat side of the musical compass.

Monologue - Beginning

KELLER: And that is when Boris goes into this, you know, internal meditation.

MORRISON: He gives a speech and it's a speech that's more or less to himself. The introduction and beginning of this monologue is in the major. It's in E, a nice, bright key associated with the coronation scene and he talks about his power.

KELLER: “I have achieved the highest power and what is it getting me?”

MORRISON: And then it parks on one of these chords when he talks about, you know, “But my soul is tormented.”

PAPE: “My soul is shaking.”

MORRISON: And suddenly, the music turns minor, brooding, deeply romantic in a lot of ways. He is somebody who is tormented by conscience. He is somebody who is covetous of power, a great deal of resentment that he's not appreciated enough for his five, six years of good and wise rule. And then when things turn bad, he's equally resentful that he is not forgiven for that by the masses or venerated sufficiently. And so over the course of this monologue, he pivots from major to minor.

PAPE: I feel like now I'm alone. Now I'm telling actually myself, “What happened? What have I done what haven't I done?”

KELLER: He's genuinely very upset that he keeps trying to help the people. And all he gets is curses and insults and suspicions of, of murder in response.

MORRISON: He seems wise and good and then bad things start to happen. The famine and the deprivation in the land, the idea that perhaps, a volcano somewhere in another part of the world caused weather disruption, which caused this great famine that stains his rule.

KELLER: He clearly had this contradictory view of his role as tsar. On the one hand, according to Muscovite governing policy at the time, the role of the people was quote “to be mute as fish.” They're just supposed to sit there with their mouth shut, like a bunch of fish and obey. And this is the world that Godunov was reared in, right? that everybody exists to serve the state.

MORRISON: And power at the top, you know, comes and goes. it's power that comes to exist in and of itself. These rulers of Russia can grab it in different ways and use it for tremendous violence upon the poor people at the bottom, the common people. This is a history that's associated with great shame because of the nature of the repressiveness of the rulers. And it's something that tends to repeat over and over again.

KELLER: On the other hand, it is also absolutely true that as famine ravaged the countryside, and in fact, there was a major fire in Moscow, Godunov went out of his way to provide help to people.

PAPE: He gave them food, he gave them houses. He gave them flats, apartments.

KELLER: Even Boris’s best efforts to help blew up in his face. He gave out grain to people in Moscow. That meant that word got around the countryside, “There's food in Moscow,” everybody came running into Moscow and they ran out of grain. So they've got all of these hungry and now angry people and nothing to feed them with.

PAPE: So he is not happy and all these leaders, all these, big names in the history, they were not happy. They had everything well. They could have all the, the, the richness, but inside the theirselves [sic], their souls, their hearts they were not happy.

KELLER: So we have Boris's meditation's on his rule to that point in the context of what maybe his ultimate motivation is, which is love for his children. So it adds a great deal of emotional depth to Boris's agonizing.

MORRISON: Then he talks about his family. And we go a couple of steps downwards until we get to this warm, flat key, very far removed from the opening E Major. On the sort of opposite side of the compass of his own identity, harmonically this idea that he's a family person. And this is actually a place where Mussorgsky introduces a theme which is really lovely. It has this kind of glow around it.

PAPE: Me as a singer, as a musician, I'm just thinking about the beauty of the music as it was written.

MORRISON: And then at the end you have, sort of like a musical mudslide, things start to fall apart. He starts to imagine a murdered child, the murder of legitimate czar. Here he breaks into something that's really loose and is more like prose. And what Mussorgsky saying is, “This is actually the truth. No more constructiveness, no more sort of artifice. This is it.” And you have this person basically exposing his own psychology talking in, you know, fairly graphic terms about this terrible vision that he's had of this murdered child.

KELLER: Mussorgsky shows us through the music, the profound conflicts of Boris. For parts of the aria, you have these beautiful, soft soaring melodies and then that's punctuated by these abrupt switches into very wild up and down angry music.

MORRISON: Any semblance of a tune that you had at the beginning all of that is gone. It's almost as though the kind of whirling thoughts and neuroses and anxieties are actually turned into sound here. It's not so much that you're hearing him sort of sweating out his fears about things, but you're actually hearing this sort of graphic musical unraveling in which you have really all of the sort of neurosis and instability of his psychology, which is a descent into psychosis.

And that's, that's how it ends. And what's fascinating about that is that you have within this monologue an anticipation of how the entire opera is going to end, because it just, the opera just sort of dissolves and this sort of entropy and malaise and uncertainty and this huge historical question, like what's going to happen next? Is this doomed to repeat?

After the Aria

KELLER: So he's already got a lot of problems. And then at 1603, apparently out of nowhere, he gets word from Poland that some unknown person has shown up claiming in fact to be the boy Dmitri Ivanovich, who as far as Godunov knew had died back in 1591. This is when he starts really putting out the story that this guy is not Dimitri at all. He's a renegade runaway monk and he's just a complete loser. Don't follow him.

So Dimitri invaded Muscovy in the fall of 1604. And so Boris really was becoming more paranoid and more violent as things got worse.

Then in the spring of 1605, Godunov himself seems to have had some kind of massive cerebral hemorrhage. He stood up. He suddenly had a fit and fell over and there was a lot of blood.

MORRISON: Boris dies during a period of protest in which there are peasants starving that rally to the Kremlin.

KELLER: And the false Dimitri is formally crowned Tsar.

MORRISON: And so you have this horrible cycle of illegitimate rulers or people who have taken control of the Tsardom of Muscovy through violence, and then they are quickly themselves dispatched.

KELLER: Historians believe that between 1604 and 1630, there were somewhere between 12 and 15 pretenders to the throne.

MORRISON: The idea of no legitimacy, the idea of chaos, the idea of a nation that was potentially under attack from foreign forces has long haunted Russian leaders. So it’s very much part of Russia’s national consciousness.

Reflections

KELLER: In some senses Russia’s identity crisis has never really entirely been settled. We have a people who want a functioning government, but it survives often, far too often these days, through corruption and through direct violence on people. But the days when they are mute as fish are long gone.

MORRISON: This is a vast and unruly and multiethnic and multi-denominational state and it was born out of brutal acquisition. It has always been a very difficult place to hold together, and the terror of no legitimacy within an autocratic system is a terror of nothing works anymore, right? There's no food, there's no roads. There's no barriers to invasion. There's chaos. And this opera is a meditation on what is the nature of power. Does it exist in and of itself that anyone can grab it? Is it something that's divine? What's incredible about the opera Boris Godunov is it's yeah, it's a great story. It's great drama. That's a big slab of Russian history put on stage. It is the history. I mean, the artwork is telling the history, it's writing the history.

GIDDENS

Music professor Simon Morrison, Russia historian Shoshana Keller, and bass René Pape…

...decoding “Dostig ja vïsshei vlasti” from Boris Godunov by Modest Mussorgsky. René will be back to sing it for you after the break.

MIDROLL

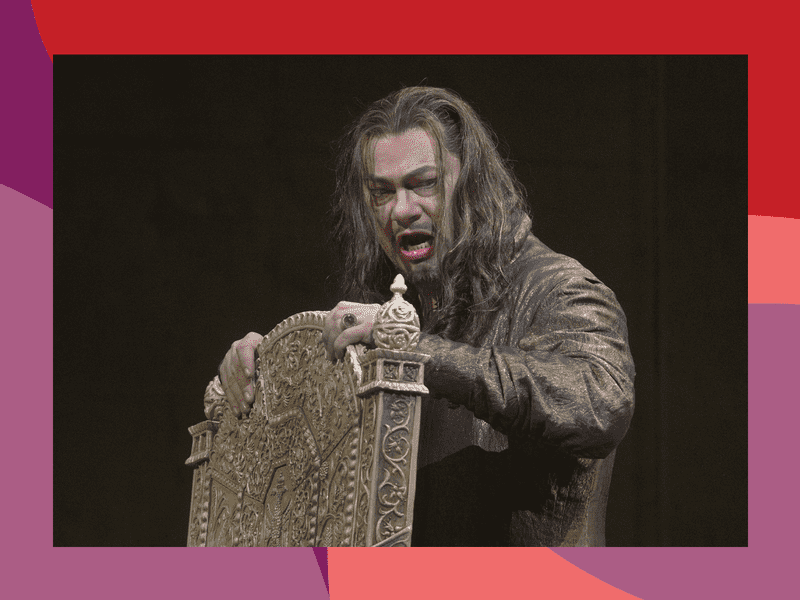

Boris Godunov is in his chambers at the Kremlin. He’s been ruling for six years, and even though he has all the power he could ever dream of, he’s miserable. He spills out everything that’s keeping him up at night in the monologue “Dostig ja vïsshei vlasti.” Here’s bass René Pape on stage at the Metropolitan Opera.

“Dostig ja vïsshei vlasti”

Boris Godunov has all the feelings in his monologue “Dostig ja vïsshei vlasti,” and you can hear every last one of them in that performance by René Pape.

Lots of feelings next time, too, when we’re back with the famous Mad Scene from Lucia di Lammermoor!

Aria Code is a co-production of WQXR and The Metropolitan Opera. The show is produced and scored by Merrin Lazyan. Max Fine is our assistant producer, Helena de Groot is our editor, and Matt Abramovitz is our Executive Producer. Mixing and sound design by Matt Boynton and Ania Grzesik from Ultraviolet Audio, and original music by Hannis Brown. This project is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts. On the web at arts.gov.

And keep on keepin’ on with those ratings and reviews! It’s a great way of helping other people find the show.

I’m Rhiannon Giddens. See you next time.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.