Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro: Count On a Reckoning

Aria Code

“Hai già vinta la causa”

from Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro

BILLBOARD

Theme music

MARCUS: This is the antithesis of justice. This is somebody abusing justice to get what he wants or punish people who deny him what he wants.

GIDDENS: From WQXR and the Metropolitan Opera, this is Aria Code. I'm Rhiannon Giddens.

BASSETT: These men really do believe that they are in a position to protect women when they are in fact the perpetrators.

GIDDENS: Every episode we unpack a single aria so we can hear it in a whole new way. Today, it’s “Hai già vinta la causa” from Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro, or The Marriage of Figaro.

FINLEY: He thinks, “Revenge. This must be the moment of revenge. I’m going to have my power. I’m going to give my sentence.”

GIDDENS INTRO

Most operas we cover on the show end in one of two ways: someone gets married or somebody dies. Either way -- when the podcast ends, you never hear from them again.

But this week's episode brings back two characters you know from last time, drawn from the plays of Pierre Beaumarchais: the handsome Count Almaviva and his bride Rosina.

Now, they bust her out of a forced marriage in Rossini’s The Barber of Seville and then their story continues with The Marriage of Figaro.

But a lot has changed.

When Mozart’s opera starts, the Count and Rosina are only a few years into their marriage, but the Count is already bored. And he’s an 18th-century Spanish lord, which means he gets to do whatever he wants with his estate and everyone on it.

The Count is especially obsessed with his wife’s maid, Susanna, who is definitely not interested. Susanna is engaged to marry the Count’s servant, Figaro. Plus, she’s loyal to the Countess, who feels neglected and lonely and just wants her loving husband back.

So Susanna, Figaro, and the Countess hatch a screwball scheme to give the Count his comeuppance. But at the beginning of this aria, the Count has gotten wind of it and that really sets him off. He’s used to being in control of everything, but now his power is being challenged and he spins into a rage.

So just to recap: A man abuses his unbelievable privilege… realizes that women are not his playthings... and he flips out.

Shocked. I’m shocked, I tell you.

So let’s see how this unfolds, both in the opera and in our world today. Ready for some introductions?

FINLEY: Yes, come on.

That’s bass-baritone Gerald Finley, who loves throwing himself into the range of emotion in the Count’s aria.

FINLEY: It's a brilliant way of characterizing anger, frustration, torment, completely within one's own mind. I had no idea when I first learned it that it would give me so much joy.

Next, Sharon Marcus, a professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University.

MARCUS: My mother was about music in our household a little bit the way Count Almaviva is about everything in his household. She decided what we were going to listen to, and we were only going to listen to classical music. So as a result, I got to hear opera every week, and I would have been about 10 or 11 years old the first time that I saw The Marriage of Figaro.

And third, Laura Bassett, a freelance journalist and a columnist for MSNBC. Laura’s written about abuses of power in politics, and the many instances of sexual harassment that have come to light in recent years.

BASSETT: It was right around early 2011 when I realized the beat I wanted to be on. There was suddenly this sort of massively coordinated political attack on abortion rights. And I kind of had a feeling that this was going to start sort of a wave of what later became, quote-unquote, the “war on women” in politics. And I think I was one of the first people that was really allowed to have that as a fulltime beat.

The world of Count Almaviva may not be as removed from ours as we might hope. Let’s peek through the windows of the Count’s castle, here’s “Hai già vinta la causa” from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro.

Background

MARCUS: The Marriage of Figaro takes place on one very long, very crazy day. And in fact, the subtitle of the French play on which the opera was based was La folle journée, the crazy day.

The whole plot revolves around whether Susanna and Figaro will succeed in getting married -- The Marriage of Figaro -- and whether Susanna will succeed in fending off the Count’s unwanted advances.

FINLEY: The very first entrance, the Count is caught effectively calling on Susanna in her room, trying to catch her alone. He has been following Susanna around and he's been trying to make appointments to meet in the gardens secretly, in his continuing ambitions to treat most everybody as property.

MARCUS: Susanna and Figaro are employed by the Count. They live in his house. He decides what room they will sleep in. He decides whether or not they will marry, because the aristocrat, the Count, is to everyone in his household as God was to humans: they are meant to respect and obey him. And in exchange, he is supposed to protect them, but of course often exploits them.

BASSETT: These abusive power dynamics exist across the board in every industry from Hollywood to tech to business. Anywhere you look there will be sort of a man at the top of the pecking order, who everyone is afraid of. As journalists we're supposed to be holding power to account, and we're supposed to be taking down these abusive people and telling these stories, and we have the same problem in our industry as well.

FINLEY: The Count has been allowed to do what he pleases and no one has brought him up on it. But The Marriage of Figaro was written around the French Revolution, and the power of the aristocracy was completely called into question. But that's the challenge: How do you confront authority without being punished yourself?

MARCUS: In a feudal system, there's an estate and the head of that estate has absolute power. And we hear a lot of references in the opera to the feudal right of the droit du seigneur. And the droit du seigneur was a right that allowed a feudal Lord to deflower a woman who was going to marry one of his vassals before the marriage. We also know that the Count has given Susanna the bedroom next to his, because he wants to have access to her, and he doesn't care that she doesn't desire him in return, but he wants her to pretend that she does.

FINLEY: He has control in every single relationship, and this is really what makes the Count the evil side of the opera.

MARCUS: But the Count doesn't want to be seen as having absolute power over everyone around him. Instead, he wants to use psychological and economic pressure.

BASSETT: We learned in the past few years how pervasive this was in the film industry with the Harvey Weinstein story. Harvey Weinstein has long been one of the most powerful men in Hollywood, and it was sort of an open secret the way that he treated women his entire career.

Harvey would have his assistant set up a meeting with a young, up-and-coming Hollywood actress who he was attracted to, and they would go meet him in a hotel room. And then he would set up this sort of quid pro quo situation where, “You do what I want you to do, and I will give you your career. And if you don't do it, then you're dead in the water as an actress.”

Basically he was allowed to continue in this behavior until there were enough women willing to come forward that they couldn't be ignored.

MARCUS: He's terrified of exposure. He talks all the time about, “Oh, this is going to be such a scandal, if people know that I'm doing this.” So he puts a lot of energy into concealment.

BASSETT: When women first started speaking out, Weinstein vehemently denied ever having done anything that was not consensual. His only crime, he said, was cheating on his wife. He acknowledged having had some sexual relations with these women, but he said that they wanted to, because he was who he was. And he got increasingly sort of angry and threatening and unhinged as reporters started to close in on him. He would randomly show up at the Times newsroom and try to go face-to-face with these reporters and threaten them. He hired Black Cube, this spy firm, to stalk and dig up information on these reporters to try to threaten them into silence. He basically thought that he could use his money and power to make this go away. And this was the first time in his life that he couldn't.

Aria Set-Up

FINLEY: So we begin Act Three with this absolute turmoil in the household. Seeing the Count on his own. He's trying to figure out exactly what is going on. He just doesn't know what to think. The Count suddenly realizes that Susanna is there.

MARCUS: Susanna tries to convince the Count that she's changed her mind and now she really does want to meet him in the garden later that night.

She's pretending that she returns his desire for her when in fact, she's only doing this as part of some plot.

FINLEY: They agree to meet in the garden. And the Count is overjoyed that Susanna has finally said, “Yes, I'm going to meet you.”

MARCUS: We, as the audience, can tell Susanna doesn't mean it, but the Count has really been convinced. And on her way out of the room, Susanna sees Figaro. And she says “Oh, don't worry, your case has already been won.”

“Hai già vinta la causa”

FINLEY: And the Count has overheard this remark.

MARCUS: And when he hears her, he realizes that they're colluding against him, that this whole sexy scene Susanna just played with him was false, and even that his power as a magistrate might be under threat, because he represents the law on his own estate. And in many productions that I've seen, as the Count sings this aria he's putting on a judge's wig and a judge's robes. He has the power to decide what is right, what is wrong. But there's really nobody in place because of that who can accuse him, and judges are supposed to be impartial, even-tempered, objective. He’s none of those things.

BASSETT: We saw this play out with the Brett Kavanaugh situation. He was nominated for a seat on the Supreme Court. So he was going to tip the balance of the Supreme Court to conservative, and he could be the deciding vote on women's abortion rights in this country. And he did have a hearing in front of the Senate, to be confirmed to the highest court in the land. And we're deciding whether he should get that massive promotion despite allegations that he attempted to rape a woman, Christine Blasey Ford, when they were in high school.

Recitative

FINLEY: So the aria begins with what is known as a dramatic recitative where the orchestra interrupts or comments on what he's thinking at a particular moment.

MARCUS: He actually begins by quoting Susanna's words, what he heard her say to Figaro, “Hai già vinta la causa.”

FINLEY: “Hai già vinta la causa.” There's no music, it's just him taking his time, saying, “I have won my case.” And then the orchestra comes in quickly full of anger, full of energy, of outrage. “I’ve fallen into a huge trap! What’s going on?” And again, the orchestra... He realizes that he's being duped, that this is the end. From this moment on, he is the object of derision. Everybody is against him.

MARCUS: He's responding to learning that he's been rejected, that he's not wanted, that he's not desired, that he may not get what he wants. So his pride and his power have been attacked. He's angry at Susanna, but he's not very focused on Susanna, except as an obstacle to his own desires. It's almost as though the first time he's gotten a glimpse of what Susanna really thinks and feels, his response is rage. You can imagine a lot of other responses, for example, this could be a moment where the Count says to himself, “Wow, she's really not that into me. She's just pretending to be into me. Why is she pretending? Maybe because she's terrified. Maybe because I'm standing in the way of what she truly wants. God, I'm kind of a jerk. Maybe I should change.” That's not the direction he goes in in this aria.

BASSETT: And so Christine Blasey Ford gets on the stand and gives an incredibly believable, compelling testimony. She had given notes to her therapist years ago about this having happened. She had told her boyfriend at the time. There was as much evidence as there could be, for a, you know, decades-old attempted rape allegation. And even in the course of this hearing, Brett Kavanaugh demonstrated some of the qualities that really make him suspect -- he was sort of contorting his face, literally crying. He's shedding tears, he's yelling, he's threatening. He said, “You're trying to ruin my life.” He's throwing a complete tantrum, a fit. I think this is a pretty common way for men to react when they feel like they're losing their grip on the power and immunity that they thought they were owed.

MARCUS: He goes on to start cursing and insulting everybody. “They're scoundrels, “Perfidi, perfidi” you don't like me. I don't like you.”

FINLEY: He's outraged and he explodes. And the orchestra does it for him. Bum, bum, bum, bum, bum: “Perfidi! Io voglio!”And then he repeats this.

MARCUS: “I want, I want.” And what does he want? “I want to punish you.”

FINLEY: Ba ba, ba ba, ba ba. “In what way will I punish you? Because I have everything at my disposal.”

The wonderful elements of change within the recitative at the beginning of the aria shows that he is outraged now, that he is being made a fool, and Mozart just delivers these emotional contrasts on a plate. The music is either just commenting on how he should feel, or how he should feel in the next moment.

MARCUS: His feelings of hurt pride and thwarted desire make him punitive, vindictive.

FINLEY: And the orchestra shows this with vigorous chords in the string section. He thinks “Revenge. This must be the moment of revenge. I'm going to have my power. I'm going to give my sentence.”

MARCUS: The sentence will be what I want. It will exist to please me.

This is the antithesis of justice. This is somebody abusing justice to get what he wants or punish people who deny him what he wants.

And what we see here is someone who's kind of deranged by hurt pride and isn't thinking very clearly, but has a lot of bluster and is like, “Yeah, yeah, I'm going to punish them all.”

BASSETT: Kavanaugh said, “You sowed the wind for decades to come,” he said to Democratic senators who were, who were questioning him about this. He said, “The whole country will reap the whirlwind.” He threatened the entire country over being questioned over what happened with this woman so many years ago. And then he was promoted to a Supreme Court Justice.

FINLEY: As the Count enters the aria he has these tremendous D major chords, which are descending from the top of the stave right down to the bottom. It's as if he's looking from on high over his kingdom. He has absolute control. And he says, “Why would I allow a servant to be happier than me? How is this possible?” And then the same descending chords.

MARCUS: The Count asks a series of questions. “Should I see my servant happy when I'm sad? Should I see my servant have something that I want that I can't get? Should I see my servant united in love to someone who arouses a feeling in me that she does not return?”

FINLEY: He's justifying now why he's so entitled to feel angry. Why should that servant possess -- and this is a very important word, “Ei posseder dovrà?” -- how could he possess this good, this chattel, who is in fact Susanna?

MARCUS: Susanna here has become a possession, a good, and the contest is really not any more between the Count and Susanna. It's between the Count and Figaro. He really sees Susanna as Figaro’s possession. And that's one of the reasons that in this aria it's Figaro he sees himself in conflict with, not Susanna.

He never mentions Susanna’s name in this aria. He never even uses the pronoun “she.” He doesn’t want to acknowledge the existence of the woman who’s made him so angry. She's erased him by not returning his desire. So he's going to erase her.

BASSETT: You won't hear from her probably ever again. Blasey Ford had to go into hiding. She got death threats for years, probably is still getting them. Her life has been completely ruined and now she will forever be associated as the woman who failed to bring down Brett Kavanaugh with a rape allegation, or attempted rape allegation. And Brett Kavanaugh is now simply a Supreme Court Justice, who ended up facing zero consequences.

FINLEY: He recovers very quickly and says, “I will not allow this servant to make this ill feeling within me.”

He then turns and imagines Figaro having this happiness that the Count doesn't have, until he says, “Will I watch,” “Vedrò?” and repeats it again, “Vedrò?” Mozart increases the volume: “Vedrò.” And a fourth time, and leaves us in a silence to wonder, what is the Count going to do now?

And we go into this statement of “I am in control.”

BASSETT: As a women's rights reporter, covering Donald Trump's candidacy in 2016 was an absolutely wild experience because first of all, he had said so many disparaging things about women. He’d called them dogs and pigs and slobs and insulted every woman that he had ever come across. There were sexual assault allegations piling up against him. And right before the election, there was an Access Hollywood tape. It was essentially him not only admitting that he sexually assaults women because he's a celebrity and rich and powerful, and because he feels like he can, but bragging about it. And it seemed to confirm all of the stories piling up of what the women were saying about him.

And he was on Fox and Friends and a woman said, “You've said such awful things about women. Um, and you've been accused by dozens of women, of sexual assault, sexual harassment, all of these things. How do you expect women to vote for you?” And he said, “Well, women love me because I'm the best candidate to protect them.” And so there's this paternal, like, “I might abuse you, but you have to love me anyway, because I am so powerful that I am the only person who has the ability to protect you in this way.” And we see it repeated over and over and over because these men really do believe that they are in a position to protect women when they are in fact the perpetrators.

FINLEY: So he switches all his inventions on Figaro.

MARCUS: This is a battle between the Count and Figaro, and his way of talking about Figaro is extremely contemptuous.

FINLEY: He says, “Ah, no, if I can't have happiness, then you, Figaro, will not have happiness. And Mozart then takes an audacious leap of a 10th in music where he sings “audace,” audacious, to reveal the audacious character of Figaro.

MARCUS: In this aria, it's all about the Count’s bluster and his vocal power. If Susanna were in the room now he'd be drowning her out.

FINLEY: Suddenly Mozart retraces and goes back to the beginning of the aria proper, “Ah che lasciar t’in pace.” And so he's, he's about to send off a whole nother diatribe against his arch enemy, Figaro. “Per dare a me tormento,” and he goes up just a little bit in the voice, a little higher. So he's thinking of this rising anxiety -- torture, torment -- and Mozart puts it in the music.

MARCUS: The Count sees himself as a victim. When people say I'm going to avenge something, they're avenging a wrong, “Something was done to me, so now I have the right to do something back.” And vengeance is what is buoying him here.

FINLEY: He's actually happy in being tormented.

MARCUS: He says, “Just the hope of my revenge consoles my soul and makes me jubilant.” We're hearing the rage feed on itself.

BASSETT: This is one of the primary characteristics of Donald Trump, right? That he loves to play the victim. So he had massive amounts of power, but he loved to act like he was the one who was being attacked. He was the one who was deserving of sympathy.

So even things that have nothing to do with him, he sees as an attack on himself. The coronavirus pandemic, for instance, he felt personally victimized by. He thought that the coronavirus pandemic had come in to ruin his reelection chances. Black Lives Matter protests. He felt victimized by that. And the same with the media, every report that even reasonably criticizes him or would talk about coronavirus death numbers, that was a direct personal attack on the president. And so I think he relishes in having an army of followers who are ready to avenge him, even when he hasn't been attacked.

Aria - End

FINLEY: And we get into the final part of this tumbling aria. The strings and flutes and everything are twittering away in absolute delight at the feelings of vengeance within the Count’s soul. And we have, [singing]. This is really the motor of the Count’s passion, the joy, his status. It's like he's dancing on air.

Now we get into this wonderful moment that all singers dread, which is, depending on how fast you're going, is the final coloratura, now this moving passage on “giubilar,” which is joy and delight and Mozart creates this gorgeous little passage where the singer has to sing all these very, very fast notes on an open “ah” vowel, as if he’s laughing, as if he's just throwing care to the wind. He's going to win. It shows that he's in complete command, he's absolutely back in control. If you're able to really control that, it's like fireworks going off. And his final flourish -- “mi fa,” -- is the top note that the Count sings in the entire opera. And it's on the word “fa,” which actually, if we all know do re mi fa, it is in fact an F, “Fa,” and so Mozart must've just completely fell over laughing when he wrote that. And once that note is over, then the entire role of the Count is so much easier than that.

Reflections

FINLEY: For me, I could only only play the Count if I have that redeeming phrase at the very end of the opera, “Contessa perdono,” “Countess, forgive me.” There is a man who is suddenly aware that his, the only way for him to gain any freedom, to gain any sense of self-worth, and for the woman who he looks straight in the eye, the Countess to be his life partner again, and accept him for the for the failings that he's had, is to sing that most sincerely. And that's a challenge because in today's society, we often don't trust those people that have said, “Sorry.” But musically speaking I have no doubt whatsoever that Mozart absolutely wanted the Count to be sincere, because it was the only way to come to a resolution.

MARCUS: I've always loved the way The Marriage of Figaro ends with order restored and loving harmony established in both the music and all the couples joining hands. The scary Count isn't so scary anymore. And I think it would be great to play this scene for optimism, that the Count has undergone some genuine change here. But I think in some ways, the end of the opera is, is a bit of a Rorschach test of someone's temperament -- are you an optimist, are you a pessimist? How you read that ending may have a lot to do with how you're feeling that day, what news stories you read recently, what stories you've heard recently from your friends. But I think it's one of the signs of a compelling work of art that things are left open and left for us to complete. You know, the job of, of changing the world that we see in The Marriage of Figaro, it's really our job. It's not the job of the characters in the opera. They haven't finished the job, but we could.

BASSETT: One important thing is just equal representation in, in Congress and in state legislatures and in the Supreme Court, which are still vast majority men, all of them. What is the expression, “If women aren't at the table, what's on the menu?” It's been 200 years, and we've never had one woman in the Oval Office, not one woman president. People don't think about that enough, how crazy that is. But, until women in power becomes more normalized and a thing that people see as they're growing up, then we're still going to have these inequities.

GIDDENS:

Journalist Laura Bassett, bass-baritone Gerald Finley, and professor Sharon Marcus decoding “Hai già vinta la causa” from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro. Gerald will be back to sing it for you after the break.

MIDROLL

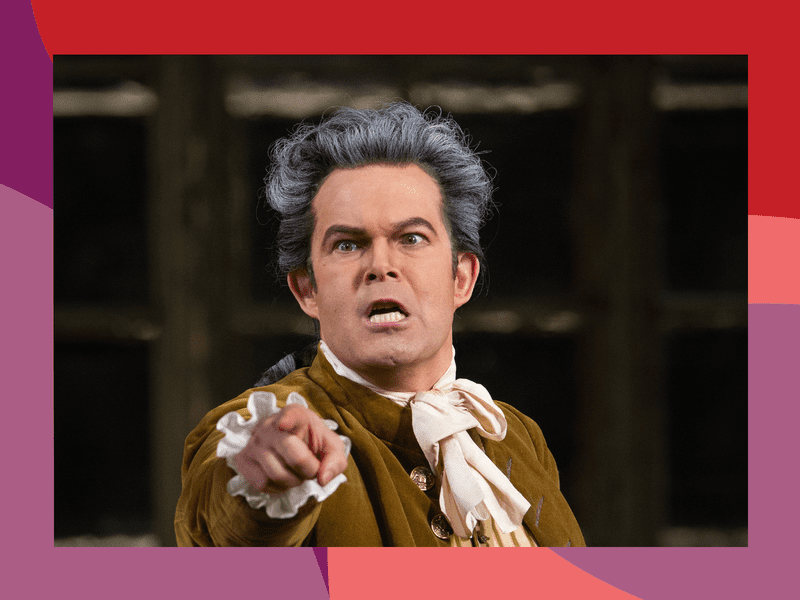

Count Almaviva is used to having his way, but his wife and servants have plans of their own, and he’s not too happy about it. Here’s bass-baritone Gerald Finley with “Hai già vinta la causa” on stage at The Metropolitan Opera in New York.

“Hai già vinta la causa”

Hell hath no fury like a man scorned! But Gerald Finley makes that fury sound so good in “Hai già vinta la causa” from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro.

In the next episode, we’ll meet a scorned woman, but not a trace of fury in her aria from The Rake’s Progress by Igor Stravinsky.

Aria Code is a co-production of WQXR and The Metropolitan Opera. The show is produced and scored by Merrin Lazyan. Max Fine is our assistant producer, Helena de Groot is our editor, and Matt Abramovitz is our Executive Producer. Mixing and sound design by Matt Boynton and Ania Grzesik from Ultraviolet Audio, and original music by Hannis Brown.

Please keep leaving those ratings and reviews in Apple Podcasts. They help other people find the show, and they make us feel all warm and squishy over here at Aria Code HQ, so thank you so much.

And also: if you’re digging the show, tell someone. There’s definitely at least one person in your life who will be happier, stronger, cooler -- a better person -- if they know the Code.

I’m Rhiannon Giddens. See you next time!

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.