The Gershwins' Porgy and Bess: Rise Up Singing

INTRODUCTION

Theme music

SMALLS: Yes, there’s hardship. And there’s beauty, there’s power, there’s spirituality, and there’s hope.

GIDDENS: From WQXR and the Metropolitan Opera, this is Aria Code. I'm Rhiannon Giddens.

ANDRÉ: Her words are saying she wants all this hope for the future. The orchestra’s telling us that maybe that’s not gonna happen.

GIDDENS: Every episode we unpack an aria so you can see what’s inside. Today, it's a song you’ve probably heard a hundred times in all different styles: “Summertime” from the Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess by George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward and Ira Gerswhin.

SCHULTZ: We have to start grappling with the kind of stories we want to tell. This cannot be the only story that we tell about the African American experience.

GIDDENS: So it’s a new year and I’ve got something really big in store for 2020: I’ll be singing the role of Bess in Porgy and Bess for the first time, back in my hometown at Greensboro Opera in North Carolina. It’s gonna be my first professional opera gig in a loooong time so it’s... a little sc—… okay, it’s a lot scary, I’m gonna be honest with you. And, you know, I’ve always had pretty complicated feelings about Porgy and Bess.

Porgy and Bess came into this world through a stellar creative team: the composer George Gershwin and his brother, the librettist Ira Gershwin, as well as novelist DuBose Heyward and playwright Dorothy Heward—yep, they were married.

Now, it was an all-white team creating a show about black life in South Carolina... which raises some important questions for me about race and representation, and to get to the bottom of them, I think we need to start at the real beginning of the story.

The how-we-got-here on Porgy and Bess begins with the Gullah, descendants of formerly enslaved people who settled along the southeastern U.S. coast, from about Wilmington, North Carolina on down to St. Augustine, Florida. A lot of folks ended up buying land around Charleston and the sea islands off of South Carolina.

Now this is where DuBose Heyward enters the picture. He’s born and raised in Charleston at the turn of the last century. He spends some time living down the street from a black tenement community called Cabbage Row. That community would become the inspiration for Catfish Row, the setting of his bestselling novel Porgy.

Porgy is about a disabled beggar who falls in love with the troubled Bess— she dates abusive men, she’s addicted to drugs, and she eventually follows her dealer all the way up to New York City, breaking Porgy’s heart.

Now one of the novel’s biggest fans is George Gershwin. He writes to Heyward and they set plans in motion to turn it into an opera.

Gershwin spends a few months just south of Charleston on James Island and Folly Beach, absorbing the language, music, and culture of the Gullah community living there. Well, as much as you can absorb in a few months.

He takes it all in and blends it with other musical influences deeply rooted in the African American community, like jazz and spirituals… And out of this fusion comes the first great American Opera: Porgy and Bess.

Now the Gershwins and the Heywards felt strongly that this story could only be told by black performers. From the very first performance, every black character has always been played by a black singer, and that’s the way it will always be -- it’s included in all performance licences by the Gershwin family.

This opera has a pretty deep history, so this episode is going to take a more expansive approach than usual.

So we’re gonna look at “Summertime”—that gorgeous lullaby. It’s sung by a new mother named Clara to her baby and it opens the entire show.

And we’ll also dip into “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’,” sung by Porgy in the style of a banjo folk tune. (It’s always good to hear banjo at the opera.)

Now let’s meet the folks who bring it all together.

First, soprano Golda Schultz...

SCHULTZ: When I become very emphatic, I become very South African.

GIDDENS: She made her role debut as Clara earlier this year and discovered that singing “Summertime” was challenging in ways she hadn’t anticipated.

SCHULTZ: The most hilarious thing about this show for me is that every woman who is a mother in real life was telling me I was holding the baby wrong.

GIDDENS: Everyone’s a critic! I have to admit, I’ve thought the same thing.

Let's just put this on the record: there is no correct way to hold a doll baby!

GIDDENS: Next, bass-baritone Eric Owens, who’s been singing the role of Porgy for a decade now.

OWENS: Ten years exactly!

GIDDENS: But his decision to play Porgy was a long time coming.

OWENS: I didn't necessarily want to get stuck just doing Porgy. And so, I had made this decision that whenever I would sing Porgy it would never be a house debut. It would have to be in a place where they weren't just wanting to typecast me.

GIDDENS: Naomi André, a professor of Afro American Studies at the University of Michigan. She’s also the author of a book called Black Opera: History, Power, Engagement. Her interest in opera began early.

ANDRÉ: My mom was always playing classical music. We had a tape player, and so we were listening that way. And then when I got to see live opera—it just—I fell in love with it. It was very easy to go to the Metropolitan Opera and get standing room tickets, so I got to see a lot of things.

GIDDENS: And Victoria Smalls, a Gullah woman born and raised on one of the Sea Islands near Charleston.

SMALLS: St. Helena Island, my home, is one of the most beautiful places I know. It's a farming and fishing community. A lot of people will come to the Island and fall in love with the landscape. And then you fall in love with the people.

GIDDENS: Victoria’s the Director of Art, History, and Culture at the Penn Center in South Carolina, an institution dedicated to promoting and preserving African American history and culture. She’s also a federal commissioner for the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor.

And by the way, the words “Gullah” and “Geechee” both refer to the same group of people and are often used together.

So now, let’s make our way to Catfish Row and the world of Porgy and Bess.

DECODE

Prologue

SCHULTZ: The first time I saw Porgy and Bess: it was my first year at the conservatory in South Africa, and I think this was really the first 20th century work I had ever seen. Until then, I'd only really listened to classical opera—I mean basically Mozart. And so there I was and the doo-wops & the wow wows, and I'm sitting there going, “What is happening? Why am I here?” But then the intro to “Summertime” starts that windy clarinet, that just like tumbles you down from the sky. Boom, spotlight hits on:

[singing] “Summertime.”

And it's the song that you've heard so many times, so many times.

If you hadn't heard in the opera, you'd heard Nina Simone do a rendition, you’d heard Ella Fitzgerald do a rendition, you'd heard everyone and their aunt do a rendition. You know the words yourself. You feel like you can hum along. And, oh, it was powerful.

And from that minute everyone in the audience cared about what was happening on that stage to every single character.

And in that moment, I had such mad crazy respect for Gershwin. For how that tune in that song just felt like home, no matter who you are or where you are.

The Music of Porgy and Bess

ANDRÉ: The music of Porgy and Bess references so many American musical styles.

OWENS: And the piece has survived because the music is so wonderful.

ANDRÉ: Gershwin just knew how to come up with snappy rhythms, wonderful undulating melodies.

OWENS: This opera is chocked full of hit tunes.

ANDRÉ: You've got “Summertime,” which is this beautiful lullaby, ballad, sort of African American spiritual style song.

OWENS: “Bess, You Is My Woman”

SCHULTZ: “It Ain't Necessarily So”

ANDRÉ: “My Man's Gone Now”

SMALLS: “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’”

ANDRÉ: The fact that you've got jazz-infused rhythms as well as African American spiritual-like sounding music—this is a little unusual.

Gershwin calls Porgy and Bess ‘a folk opera’ to explain what he's doing.

OWENS: Gershwin was very diligent about making sure that he captured the essence of the community through his music. And he's so masterful in the way that he blends all of that together: this wonderful fusion of genres, that flow seamlessly from one to another.

SCHULTZ: Porgy and Bess has so many good tunes that you can’t forget. There's some really dark, difficult stuff happening with those people.

SMALLS: Gullah Geechee people—‘We people,’ we say—we’re the descendants of Africans who are enslaved on rice, indigo on Sea Island, cotton plantations.

People that are stolen away from West Africa as part of the transatlantic slave trade—1600s, 1700s—and we’re brought into the ports of Charleston, and areas of Savannah, Georgia, up North. But primarily, Gullah Geechee people are entering into the Charleston Harbor; to maybe Gadston’s Wharf.

80% of us enter into the nation as enslaved people and take our first steps. And at Gadston’s Wharf is going to be a warehouse that houses us until the market is right to sell us. Like cattle or corn. And, this is where we are melding together, this is where we're trying to survive, but also learn who we are as enslaved people in the United States.

Catfish Row

ANDRÉ: A lot of people say that the creative team for Porgy and Bess is an all-white team, and how do they have any right representing black culture? And I like to challenge that assumption. We know that DuBose Hayward, who wrote the novel “Porgy” in 1925, was from Charleston, South Carolina. George Gershwin had a different background. His parents were from Russia and Lithuania, and he and his siblings were born in Brooklyn, New York. And they were also Jewish. And being Jewish in the 1930s here in the United States was not exactly being white.

Gershwin is bringing in his special position as a Jewish composer, figuring out what American music is like, at a time when the United States was coming out of a European classical tradition, but also figuring out what is Americanness.

SMALLS: The very nature of the Gullah Geechee’s enslavement created just this unique culture with the deep African retentions, very deep roots. Many plantation owners relied on other enslaved Gullah people to run the day-to-day plantation life as overseers or task masters. We had very little interaction with the very people that enslaved us. And then that isolation served as this beautiful incubator, protecting the Gullah Geechee culture. And helping it to remain intact for many years, in many generations.

And with this, we have very distinctive and unique arts, crafts, food ways, music, religion, spiritual practices. Things that we have kept even through enslavement, even through migration.

And Gullah Geechee people, we people, remain proud culture keepers.

OWENS: Well, we are in Charleston, South Carolina, in the community of catfish row.

And we have this group of people who are more like a big family than just a neighborhood of people. And in it, you have the upwardly mobile couple in Clara and Jake. Jake owns his own business, and he talks about working hard, sending his son to college.

SCHULTZ: They're the yuppies of the community. Like if they were gentrifying Catfish Row, they'd be out there getting that wonderful, like, loft apartment. And they'd be the ones who would be drinking all the green smoothies, and saying things like, “We only use biodegradable everything for our baby.”

OWENS: And I play the role of Porgy: one of the pillars of the community even though he has this disability. He's unable to walk, he's usually on a cart close to the ground, and he propels himself forward with both of his hands.

ANDRÉ: He is a man who doesn't have a whole lot. His main work is to go into the white city, and to beg, to ask for money. And so he represents one of the more humble members of this community. And yet he is our central focus.

OWENS: And even though he's not quote unquote “able-bodied,” he is a complete person. He's a person of integrity and he has a good heart.

ANDRÉ: Porgy and Bess does a wonderful job of giving us a community of black folks in the first half of the 20th century. One of the problems, though, is that it relies too much on these negative stereotypes from minstrelsy. Things that come out of the 1820s and ‘30s, that led to these skits where you would have images of black people as not being fully rounded characters; the happy-go-lucky, “I'm not going to cause any trouble” type of black man. So Porgy is a good example. One of the challenges, to the cast singing Porgy and Bess, is to move past that, giving a more three-dimensional characterization to these roles.

SCHULTZ: What was Gershwin trying to write? What was DeBose Heyward trying to write? They were trying to write about fringe societies that people don't necessarily see. And also choose to ignore, sometimes. That fringe societies go through the same things “normal society,” in quotation marks. We all go through the same things. We all aspire, we all struggle.

So it's very interesting to look at this tiny pocket of a society because, speaking as a South African, even a majority of the population—who are people of color—we were treated as a fringe society. So having this story out there and giving it legitimate space is exciting.

“Summertime” - First verse

ANDRÉ: One of the incredible show stopping numbers that happens early in the opera is this amazing moment when Clara sings, “Summertime.” The men are coming home, as the women are cooking dinner. And you've got all of this action happening; the energy in the orchestra.

Then, all of a sudden the dramatic action slows down and she's singing this lullaby. And it's a wonderful opening to this opera because it gives us the youngest member of the community and what the future, and dreams, hold for this young person.

SCHULTZ: “Summertime” definitely has the wonderful quality of being a lullaby. It's beautiful in its simplicity. Just like easy little syncopations that always make you either step away from, or lean on, the one beat. You step away, or you lean in; you step away, or you lean in.

So it's the action of rocking a child. You hear it, and your body responds.

OWENS: It's some of the most beautifully written music of the 20th century. And it's all about one's hopes and dreams for their children.

SCHULTZ: The first verse you say, “Summertime/ and the livin’ is/ easy/fish are jumpin’.” You know, when a fish jumps, it has to go up to come down. So you start at the top and instead of going, “Fish are jumpin’,” it's this really, really cute thing of, “Fish are ju-uhumpin’.”

There’s these wonderful grace notes; it’s a little extra bonbon of sound. And just that “ju-uhumpin’,” you really get that sense of, “Oh! There goes a fish jumping in the river. Oh! There it is again.”

SMALLS: My father, he would go on the river. “In da ribba”—in the river— and he would go in his Gullah Bateau—a flat bottom boat. And he would fish with a Gullah cast net— hand-sewn. And you swing it out, then the weight of it falls to the bottom of the water and captures a bounty of fish, and shrimp, and yucky squid that you don't want. And other things—“udda tings, udda tings” in a net. And so I remember one day in particular, we were out and the fish were jumping high, you know, he would know where to go. And, I decided to jump out of the bateau and go swimming along in the river while my father was fishing. And I realized why the fish were jumping high—it’s because a dolphin was approaching, and actually gathering the fish for us. Isn't that just amazing?

ANDRÉ: She sings a line that’s pretty straightforward, harmonically. It represents these intentions she has, that are so pure, and so honest and heartfelt. And yet, what makes the song really come together is what's happening in the orchestra. The orchestra gives us a supportive background, but it's also showing some conflict where things are at odds. There's so many seventh chords. Those are chords that are harmonically unstable. They're exciting and they're crunchy for all the different potentials of what key you can go to. But it means that it's not rooted in a home key. Clara is out there putting her best forward, and yet the environment she's enmeshed in is not stable, though her words are saying she wants all this hope for the future. The orchestra is telling us that maybe that's not going to happen. Maybe something is going to shift.

SMALLS: When I'm driving down the road in some areas, traveling in South Carolina, there are still some areas where you see cotton being grown. That cotton symbolizes slavery for me. And all I can see is my people toiling, working, slaving. But then on the other side of that, I see a symbol for self-sufficiency. And that is because in 1861 union forces came and occupied the sea islands, emancipating us; and they're coming in November because Sea Island cotton is ready to harvest. The cotton is high and is ready to be picked. But for the first time, when they pick this cotton, they will get paid $1.25 for 400 pounds of cotton.

Also during this time, you can buy an acre of land for $1.25. So these lyrics and the cotton is high, is making me feel very sad about my enslaved ancestors. But it's also that symbol of hope: you have land that cannot be confiscated from you; you have land, and you were able to buy it for a $1.25. The same amount to pick that cotton.

It means so much more than just being paid.

SCHULTZ: “Summertime” is definitely a song that deals with that balance between hope and uncertainty, and that’s very prevalent in that community. But it’s important that even in all of that conflict, there’s still a community of people who generally like each other and want to be with each other.

And when you hear Porgy sing “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’,” he’s sitting in the middle of the Courtyard of Catfish Row surrounded by children listening to him just wax lyrical and poetic about, “It’s okay to have nothing, but there’s actually so much more that we have because we have each other.” Even in all of the turmoil, that’s the real story.

“I Got Plenty o' Nuttin'”

OWENS: “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’” is basically a folk song. There's this steady underpinning to it. You know “boom chick boom chick boom chick:” a dependability. And you have the banjo playing along with him, so it's very folksy and very earthy.

ANDRÉ: The banjo is associated with the African American community. It's thought to be one of the instruments that was brought over—very unusual in the opera orchestra. And so, the banjo really has this nice signifier of African American culture.

Porgy is the title character and we're waiting to hear his big solo moment. And it seems on the surface he's saying nothing.

OWENS: He's got plenty of nothing. Nothing, being that it's not a tangible good that he possesses that somebody can take away.

He's got his gal, his song, and he’s got his Lord. He gets to sing, and he has a reason to sing because of his gal, given to him by his Lord.

When Bess comes into his life, he experiences romantic love and it awakens something in him. All the colors are brighter and everything tastes better. When you're feeling a love like that, you don’t need anything else. You're being filled up. No amount of money can make you feel that way.

SMALLS: That song really speaks to the self-reliance and self-sufficiency of Gullah Geechee people. Maybe they have some land, maybe they don't. But they have their family; they have their Lord and that’s enough, that’s plenty.

OWENS: He says, “Folks with plenty o’ plenty, they have to lock their door. They're afraid someone's going to come and take these possessions.” Ultimately what are these possessions for and what is money for. People try to buy their way to happiness sometimes.

SMALLS: He doesn't even lock his door because he has nothing to—there’s nothing to take. There's nothing to take, and there's the people with the plenty and then they got to lock their doors. That is so true. On my farm, when I was growing up, we had one little latch on our screen door. That was all we used to lock our door.

OWENS: There's a simplicity there; and simplicity doesn't mean uninteresting. We strive for a certain simplicity in our lives which is fleeting.

SMALLS: And I just love hearing this beautiful language melded into these songs, like “got Hebben the whole day long.” Hebben: we take off that ‘v’ and we put on a ‘b’. That is characteristic of the Gullah language.

And “Lawd [Lord].” Lawd, with an ‘L’ ‘A’ ‘W’ ‘D.’ That is a signifier that you come from a Gullah community and it comes through in your speech and your language; and that is beautifully depicted throughout Porgy and Bess.

OWENS: He didn't realize before Bess came along what exactly happiness was; and he's all in—to the point of even killing for her. But then she breaks his heart. His whole world just falls to pieces when he finds out that she's gone to New York. And he's like, “What's New York? Where is it? Well, damn it. I'm going, and I'm going to find her.”

Now, you know you can argue, “Well, does he make it?” No, hahaha. He's crippled. He's got five dollars in his pocket—if that. Anyway.

“Summertime” - Second Verse

SCHULTZ: One of the things that Porgy and Clara actually share between them is they’re extremely hopeful people. They believe that there’s a brighter future. Clara says it beautifully in the second verse: “One of these mornings/you're going to rise up singing/then you'll spread your wings/and you'll take the sky.”

So that for me is extremely aspirational.

Clara hopes for a better life for her child.

SMALLS: She's prophesizing what it is that she wants for this child in the future. And I say that because my first child was three months old when my father died; and the first thing that my father did when I came home from the hospital and took my baby over to him—he grabbed my son, went away in a room alone, and started singing to him. Almost as if my father knew that he was not going to be around long enough to fill my son with his hopes and his dreams and his desire for his future. But the song that he sung to my son just put it in there—he soaked it all up.

SCHULTZ: So you start the aria by yourself, so it's kind of this solitary moment. But then what’s really lovely about the second verse is you hear wonderful sopranos and altos and the chorus surrounding them, singing, “Ooh.” And it's all just women singing; women at work; women in their life.

SMALLS: When Clara is singing this song, she represents exactly what I see within the Gullah women, in all Gullah communities. The women are the healers. We call them aunties, we call them big mamas, we call them grammys, we call them all these different terms of endearment and love.

SCHULTZ: They're kind of just enveloping you in harmony and you can just enjoy being a part of the fabric which musically helps to establish the idea of community. And I think Gershwin did that for a reason. He wanted this to be a story of this whole cosmos that is Catfish Row

The Hurricane (“Summertime” reprise)

SMALLS: So in the opera, we know that this hurricane comes and wipes away Jake and Clara, and this baby is left alone.

SCHULTZ: In the hurricane scene, the orchestra is monstrous and wants to overwhelm, and that flute comes in there trilling on that E: “blahlalalalala,” and it’s like a bell ringing in your head. Alarm bells are going off.

The second verse is the verse that gets repeated. Not the first verse; not the very lullaby kind of verse; you know “Summertime/and the livin’ is easy.” That would be a way to comfort, but somehow this bit about rising up into the sky, going forward… It kind of has this battle cry effect.

So this one song takes on so many formulations and can mean so many different things, and it stops being just pretty singing, and it starts to be the reason people come to theatre. It becomes live art happening.

ANDRÉ: For me, one of the toughest parts about the opera is that we have these wonderful, incredible characters that are put forth in the beginning and through the opera, and then there's so little hope at the end. The two people who we’re the most excited about in the very beginning—Clara and Jake, and their little baby—and there's so much hope for what's going to happen. You know, “This little kid is going to go to college. This kid is going to do everything, grow up, and be everything we want.

And, you know, in the second act, the hurricane comes and Jake is wiped out, Clara is wiped out. The baby's handed to Bess. Bess ends up not being able to take care of the child, and where we had so much promise and hope, the ending is so devastating.

Reflections

OWENS: When this piece was premiered, there were very few images of black people in film and television and on the stage and it was mostly, you know, people being underlings, so to speak. And now since that's no longer the only thing you see, you have more freedom to present this as the story that it is. And people still don't buy into it. But I think that Dubose Heyward and the Gershwins, I think they're not being disparaging of this community. They are just trying to tell the story of how it was.

SCHULTZ: But we have to start grappling with the kind of stories we want to tell: the African-American experience; any sort of diasporic experience cannot just be told through their pain. It must also be told through their joy.

And we have to also push for incorporated stages, not just every once in a while, you know. This was actually for me the first time since being a student in South Africa, that I was in a cast with so many singers of color. And this cast is proven to the entire public that there's talent. It’s just that people haven't been looking. And it's sad. And it kind of makes me angry.

ANDRÉ: I have a lot of friends who have very mixed views about this work, but there's something really relevant and timely. We have issues around race, where white supremacy is something we think about, and black lives matter is something we think about. We live in the MeToo era, where we think about sexual harassment and really what power is doing. This opera also brings up ability and disability, drug abuse, and violence—and what does it mean for a community that has had extreme violence against them. We're still, in the time of the opera, not that far from slavery and we're in a sharecropping world, with Jim Crow and lynching as very real issues. How does this have meaning today? It has a lot of meaning today. And so, I'd like to think that with this context and the background of understanding the complications of the work, this is a liberating space for those who choose to come into it and let themselves be moved by the performances.

SMALLS: So even though the Gullah culture, my culture, is filled with people who are self-reliant, self-sufficient—this generation and its traditions being passed on—it's still at risk to be extinct or vanish.

You know, you can look at me and just hear me. What you hear today is not what I sounded like growing up Gullah on St. Helena Island. What you would have heard was, if I wanted to greet you: [Gullah language]. And if I was saying goodbye to you, I would say, [Gullah language]. My first language was Gullah and I stopped because if I just went seven miles inland, people would laugh at me. And this is what you hear today. You hear a little bit of the Gullah coming out—“teday” [Gullah language]—you hear a little bit of it coming out, but I lost a lot of it because I was ashamed.

So, some aspects of our culture are diminishing and some of it is resilient. That's a word that I—I love when I talk about my culture: resilient.

And when I think about this magnificent work of Porgy and Bess, I really see this as a tool for continuing generations to be able to look at, and listen, and feel, and really see the beauty of the Gullah culture. Yes, there's hardship. And there's power, there’s spirituality, and there's hope.

Hope.

Hope.

GIDDENS: That was Victoria Smalls, a Gullah Geechee cultural heritage comissioner, bass-baritone Eric Owens, professor and writer Naomi André, and soprano Golda Schultz, decoding “Summertime” and “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’” from the Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess by George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward and Ira Gerswhin.

Golda will be back to sing “Summertime” for you after the break.

MIDROLL

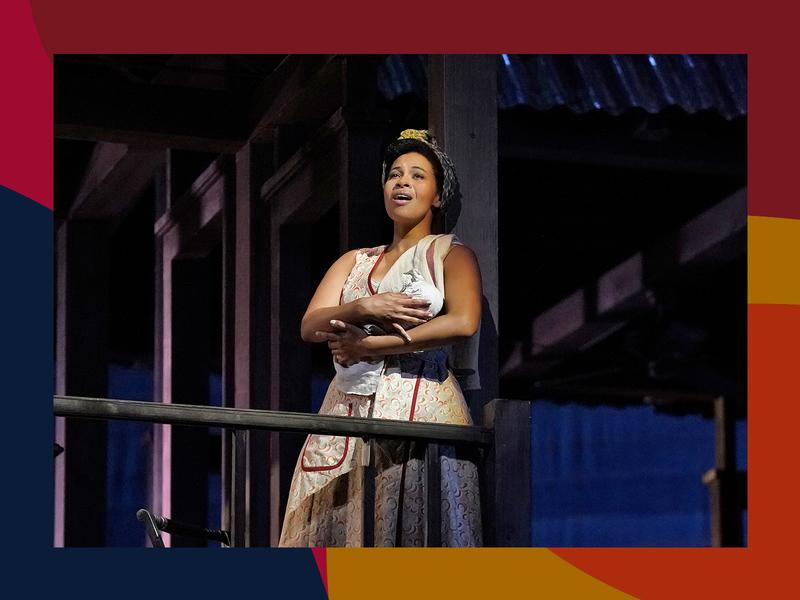

GIDDENS: Porgy and Bess opens with the lullaby, “Summertime,” as Clara sings to her newborn child. Here’s Golda Schultz singing it, onstage at the Metropolitan Opera.

ARIA - "Summertime" performed by soprano Golda Schultz

GIDDENS: I mean, there’s a reason everybody loves this song.

It’s time to wrap up the first Aria Code of 2020. I hope you had a chance to catch up on any episodes you missed during our little break. And hey, if you’re enjoying the show, you can head on over to Apple podcasts and spread the joy by leaving a rating or review. Oh, and to the reviewer who said that Aria Code is one of the top podcasts that has ever existed… you’re now one of my favorite Aria Coders (Okay, okay… you’re all my favorites, but especially you).

Aria Code is a co-production of WQXR and The Metropolitan Opera. The show is produced and scored by the magical operatic unicorn who we mortals know as Merrin Lazyan. Emily Lang is our associate producer, Brendan Francis Newnam and Helena de Groot of Public Address Media are our editors, and Matt Abramovitz is our Executive Producer. Sound design and mixing by Matt Boynton and Ania Grzesik, and original music by Hannis Brown.

The worldwide copyrights in the works of George Gershwin and Ira Gershwin for this presentation are used by permission from the Gershwin family.

I’m Rhiannon Giddens. See ya next time!