BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

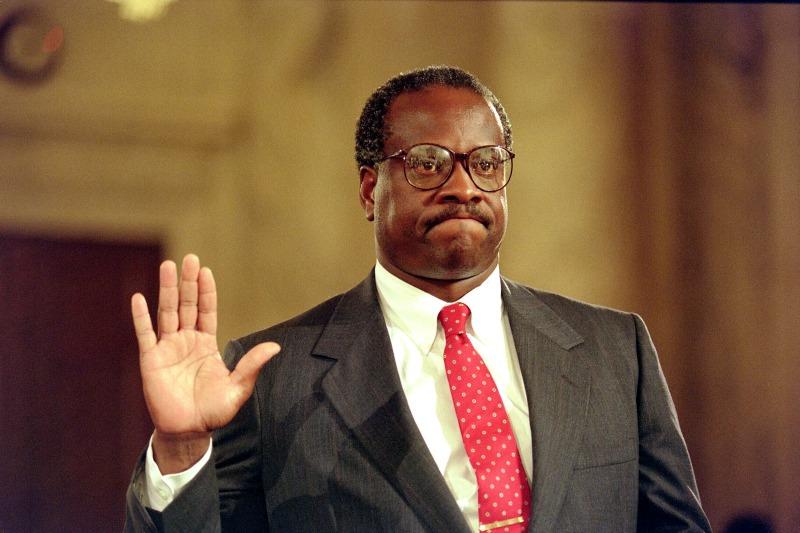

This weekend, HBO airs the movie Confirmation, marking the 25th anniversary of the sensational televised confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas. Nominated in 1991 by President George H. W. Bush to succeed liberal Justice Thurgood Marshall, Thomas raised eyebrows with his less-than-sterling legal pedigree, but the hearings were destined to be more formality than show trial, until the late emergence of an Oklahoma law professor named Anita Hill, who recounted episodes of sexual harassment during her two stints in Thomas's employ. Once she told that story, all hell broke loose. This is Republican Senator Arlen Specter interrogating Hill in 1991.

[CLIP]:

SEN. ARLEN SPECTER: …you are not now drawing a conclusion that Judge Thomas sexually harassed you.

PROF. ANITA HILL: Yes, I am drawing that conclusion. That is my-

SEN. SPECTER: Well, then I don’t understand.

PROF. HILL: Pardon me?

SEN. SPECTER: Then I don’t understand.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Dahlia Lithwick, legal affairs correspondent at Slate and host of the Amicus podcast, has seen the movie. Dahlia, welcome back to the show.

DAHLIA LITHWICK: Thank you for having me, Bob.

BOB GARFIELD: First of all, did they get it right?

DAHLIA LITHWICK: You know, there’s going to be a lot of fighting about whether they got it right. We've already heard some pushback from several senators. Alan Simpson doesn't like his portrayal, Jack Danforth doesn't like his portrayal. I think Joe Biden doesn't much like it. I will say, this was meticulously researched. A lot of the key moments that you see in the film are verbatim. They tried really hard to convey the idea that we are not going to relitigate this, we’re going to show it to you and you figure out what you think.

BOB GARFIELD: As you say, the movie was completely agnostic on Clarence Thomas's character, apart from this unbelievable testimony that was coming from her mouth. Kerry Washington who played Professor Hill played it extremely reserved and extremely in control in otherwise just a completely out-of-control situation.

DAHLIA LITHWICK: What Kerry Washington really ably captures is that quality of just being all alone. The Democrats on the committee more or less abandon her. The process, as I think is transparently obvious from the film, is not fair. There she is, sitting by herself at a table answering insane questions for hours and hours.

[CONFIRMATION CLIP]:

MALCOLM GETS AS SEN. SPECTER: You drew an inference that Judge Thomas might want you to look at pornographic films, but you told the FBI specifically that he never asked you to watch the films. Is that correct?

KERRY WASHINGTON AS PROF. HILL: He never said, let's go to my apartment and watch films. He did say, you ought to see this material.

SEN. SPECTER: But when you testified, as I wrote it down, “We ought to look at pornographic movies together,” that was an expression of what was in your mind.

PROF. HILL: That was the inference that I drew, yes.

[END CLIP]

DAHLIA LITHWICK: And it’s so striking, you know, this whole committee is comprised, at the time, of white men, and they’re so out of their depth on handling both these very fraught questions of race and of gender.

I interviewed Professor Hill two years ago and she said, I thought, the most revelatory thing. She said what she learned after this process was that Clarence Thomas had a race and she had a gender, that what the committee did was that they afforded him race. She was not a black woman, she was just a woman. And this is so masterfully handled in the film, when Wendell Pierce delivers that lynching line.

[CONFIRMATION CLIP]:

WENDELL PIERCE AS CLARENCE THOMAS: And from my standpoint as a black American, as far as I’m concerned it's a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks.

[END CLIP]

DAHLIA LITHWICK: They are so overmastered by his claim that he is being lynched by her, an African-American woman, that at that moment she realizes it’s over because all she has is gender. And this litany of stereotypes about how she's an erotomaniac, she's lifting material from The Exorcist, throwing herself at him. And so, you get these kind of Shakespearean tropes about her as this spurned woman.

BOB GARFIELD: One thing that movies and television are really good at is putting beautiful people in front of cameras. What they’re not great at is faithfully recreating really anything that has to do with the machinery of government and the judicial system. How did these filmmakers do?

DAHLIA LITHWICK: I think they did really well. And I think what the filmmakers here said is this was never [LAUGHS] a legal process. You come away saying, unh-uh, this has the trappings of the quasi-judicial, quasi-investigatory body, but what it really was, was just blood sport. The film opens with the borking of Robert Bork, and you realize just the shimmering incandescent rage that animates the Republicans on this committee who have been thwarted.

[CONFIRMATION CLIP]:

BILL IRWIN AS SEN. JOHN DANFORTH: This is a street fight, Joe, and if a friend of mine is attacked in a street fight, I’m gonna pick up a crowbar.

[END CLIP]

DAHLIA LITHWICK: This, in some sense, [LAUGHS] had very little to do with Anita Hill, until it had to do with Anita Hill. This had to do with absolute fury on the part of Senate Republicans that Bork did not get his seat.

BOB GARFIELD: I want to ask you about Professor Hill. She seemed, at least to me and other sympathetic ears, that she was a victim of just an extremely ugly and destructive political process and that she was being made to pay a price for sins of the past. But what I think the film makes clear, and actually explicitly clear at the end, is that she is not so much a victim as a martyr for a cause that led to, at a minimum, greater awareness of a nasty reality of sexual harassment, and then also led to having more women in places of power, in the Congress and elsewhere.

DAHLIA LITHWICK: That's right, and I think one of the most achingly powerful scenes happens at the very end of the movie where she goes back to her office in Oklahoma and there are stacks and stacks of mail. All these women who haven't spoken out, who have been abused and humiliated and degraded and stayed on the job because they need a paycheck, all of them write to her. I don't even know if she'd use the word “martyr.” I think she'd say, look, I became a symbol. It became important for me to sit there and answer questions about why a woman would stay.

[1991 HEARING CLIP]:

SEN. ALAN K. SIMPSON: When he left his position of power or authority over you, why in God's name would you ever speak to a man like that the rest of your life?

PROF. HILL: That's a very good question. I have suggested that I was afraid of retaliation, I was afraid of damage to my professional life. And I believe that you have to understand that this response - and that's one of things that I have come to understand about harassment - that this kind of response is not atypical.

[END CLIP]

DAHLIA LITHWICK: And it was so patently clear that the senators on the Judiciary Committee who kept saying incredulously, [LAUGHS] why didn’t you report this, why did you stay, the idea that without being touched that could still be harassment, that was unthinkable in that moment in time. And now we all understand that a man doesn't have to hurt a woman or dock her paycheck in order to be guilty of sexual harassment.

So I think by almost every measure, we can say, yes, it moved the needle, yes, it created awareness. The national conversation now stipulates and understands that this happens, it happens too much, that they are legal remedies and that there are things women can do. And that really, really is a profound sea change.

BOB GARFIELD: You know what the other silver lining is, Dahlia? The political polarization that characterized the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings, 25 years later, as we look at a new nominee, Merrick Garland, for the High Court, it's all just faded away and now the Senate will collegially consider the President's nominee and give its advice and consent and move the process seamlessly along. We’ve come such a long way.

DAHLIA LITHWICK: [LAUGHS] You know, I was so struck when I watched this movie this week that we thought that was a constitutional crisis, right? I mean, we watched that riveted, three days of pre-Kardashian Kardashianism. And then you look at today, where I think we really are on the precipice of something that looks like a constitutional crisis, but there's no sex, there's no drama, there's nothing. There’s just a 62-year-old white guy who gets up and goes to work every morning. And to me it's so striking, the way that that moment in history came alive for us because we watched it on television, because we got to be a part of it; we got to see ourselves in that: Do I believe him, do I believe her?

Now we have [LAUGHS] a nominee who is a legitimate nominee. We should be having a process that's existed for centuries in this country, and yet, because there's no story to tell - there's no drama, there's no TV - it's like it's not even happening.

BOB GARFIELD: Dahlia, as always, thank you very much.

DAHLIA LITHWICK: As always, it's a joy to be with you.

BOB GARFIELD: Dahlia Lithwick, legal affairs correspondent at Slate and host of the podcast Amicus.